Combining Polynomial Chaos Expansions and the Random

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Introduction to Mathematical Modelling

An Introduction to Mathematical Modelling Glenn Marion, Bioinformatics and Statistics Scotland Given 2008 by Daniel Lawson and Glenn Marion 2008 Contents 1 Introduction 1 1.1 Whatismathematicalmodelling?. .......... 1 1.2 Whatobjectivescanmodellingachieve? . ............ 1 1.3 Classificationsofmodels . ......... 1 1.4 Stagesofmodelling............................... ....... 2 2 Building models 4 2.1 Gettingstarted .................................. ...... 4 2.2 Systemsanalysis ................................. ...... 4 2.2.1 Makingassumptions ............................. .... 4 2.2.2 Flowdiagrams .................................. 6 2.3 Choosingmathematicalequations. ........... 7 2.3.1 Equationsfromtheliterature . ........ 7 2.3.2 Analogiesfromphysics. ...... 8 2.3.3 Dataexploration ............................... .... 8 2.4 Solvingequations................................ ....... 9 2.4.1 Analytically.................................. .... 9 2.4.2 Numerically................................... 10 3 Studying models 12 3.1 Dimensionlessform............................... ....... 12 3.2 Asymptoticbehaviour ............................. ....... 12 3.3 Sensitivityanalysis . ......... 14 3.4 Modellingmodeloutput . ....... 16 4 Testing models 18 4.1 Testingtheassumptions . ........ 18 4.2 Modelstructure.................................. ...... 18 i 4.3 Predictionofpreviouslyunuseddata . ............ 18 4.3.1 Reasonsforpredictionerrors . ........ 20 4.4 Estimatingmodelparameters . ......... 20 4.5 Comparingtwomodelsforthesamesystem . ......... -

Clustering and Classification of Multivariate Stochastic Time Series

Clemson University TigerPrints All Dissertations Dissertations 5-2012 Clustering and Classification of Multivariate Stochastic Time Series in the Time and Frequency Domains Ryan Schkoda Clemson University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_dissertations Part of the Mechanical Engineering Commons Recommended Citation Schkoda, Ryan, "Clustering and Classification of Multivariate Stochastic Time Series in the Time and Frequency Domains" (2012). All Dissertations. 907. https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_dissertations/907 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Dissertations at TigerPrints. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Dissertations by an authorized administrator of TigerPrints. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Clustering and Classification of Multivariate Stochastic Time Series in the Time and Frequency Domains A Dissertation Presented to the Graduate School of Clemson University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy Mechanical Engineering by Ryan F. Schkoda May 2012 Accepted by: Dr. John Wagner, Committee Chair Dr. Robert Lund Dr. Ardalan Vahidi Dr. Darren Dawson Abstract The dissertation primarily investigates the characterization and discrimina- tion of stochastic time series with an application to pattern recognition and fault detection. These techniques supplement traditional methodologies that make overly restrictive assumptions about the nature of a signal by accommodating stochastic behavior. The assumption that the signal under investigation is either deterministic or a deterministic signal polluted with white noise excludes an entire class of signals { stochastic time series. The research is concerned with this class of signals almost exclusively. The investigation considers signals in both the time and the frequency domains and makes use of both model-based and model-free techniques. -

Random Matrix Eigenvalue Problems in Structural Dynamics: an Iterative Approach S

Mechanical Systems and Signal Processing 164 (2022) 108260 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Mechanical Systems and Signal Processing journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ymssp Random matrix eigenvalue problems in structural dynamics: An iterative approach S. Adhikari a,<, S. Chakraborty b a The Future Manufacturing Research Institute, Swansea University, Swansea SA1 8EN, UK b Department of Applied Mechanics, Indian Institute of Technology Delhi, India ARTICLEINFO ABSTRACT Communicated by J.E. Mottershead Uncertainties need to be taken into account in the dynamic analysis of complex structures. This is because in some cases uncertainties can have a significant impact on the dynamic response Keywords: and ignoring it can lead to unsafe design. For complex systems with uncertainties, the dynamic Random eigenvalue problem response is characterised by the eigenvalues and eigenvectors of the underlying generalised Iterative methods Galerkin projection matrix eigenvalue problem. This paper aims at developing computationally efficient methods for Statistical distributions random eigenvalue problems arising in the dynamics of multi-degree-of-freedom systems. There Stochastic systems are efficient methods available in the literature for obtaining eigenvalues of random dynamical systems. However, the computation of eigenvectors remains challenging due to the presence of a large number of random variables within a single eigenvector. To address this problem, we project the random eigenvectors on the basis spanned by the underlying deterministic eigenvectors and apply a Galerkin formulation to obtain the unknown coefficients. The overall approach is simplified using an iterative technique. Two numerical examples are provided to illustrate the proposed method. Full-scale Monte Carlo simulations are used to validate the new results. -

![Arxiv:2103.07954V1 [Math.PR] 14 Mar 2021 Suppose We Ask a Randomly Chosen Person Two Questions](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7197/arxiv-2103-07954v1-math-pr-14-mar-2021-suppose-we-ask-a-randomly-chosen-person-two-questions-757197.webp)

Arxiv:2103.07954V1 [Math.PR] 14 Mar 2021 Suppose We Ask a Randomly Chosen Person Two Questions

Contents, Contexts, and Basics of Contextuality Ehtibar N. Dzhafarov Purdue University Abstract This is a non-technical introduction into theory of contextuality. More precisely, it presents the basics of a theory of contextuality called Contextuality-by-Default (CbD). One of the main tenets of CbD is that the identity of a random variable is determined not only by its content (that which is measured or responded to) but also by contexts, systematically recorded condi- tions under which the variable is observed; and the variables in different contexts possess no joint distributions. I explain why this principle has no paradoxical consequences, and why it does not support the holistic “everything depends on everything else” view. Contextuality is defined as the difference between two differences: (1) the difference between content-sharing random variables when taken in isolation, and (2) the difference between the same random variables when taken within their contexts. Contextuality thus defined is a special form of context-dependence rather than a synonym for the latter. The theory applies to any empir- ical situation describable in terms of random variables. Deterministic situations are trivially noncontextual in CbD, but some of them can be described by systems of epistemic random variables, in which random variability is replaced with epistemic uncertainty. Mathematically, such systems are treated as if they were ordinary systems of random variables. 1 Contents, contexts, and random variables The word contextuality is used widely, usually as a synonym of context-dependence. Here, however, contextuality is taken to mean a special form of context-dependence, as explained below. Histori- cally, this notion is derived from two independent lines of research: in quantum physics, from studies of existence or nonexistence of the so-called hidden variable models with context-independent map- ping [1–10],1 and in psychology, from studies of the so-called selective influences [11–18]. -

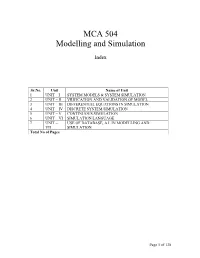

MCA 504 Modelling and Simulation

MCA 504 Modelling and Simulation Index Sr.No. Unit Name of Unit 1 UNIT – I SYSTEM MODELS & SYSTEM SIMULATION 2 UNIT – II VRIFICATION AND VALIDATION OF MODEL 3 UNIT – III DIFFERENTIAL EQUATIONS IN SIMULATION 4 UNIT – IV DISCRETE SYSTEM SIMULATION 5 UNIT – V CONTINUOUS SIMULATION 6 UNIT – VI SIMULATION LANGUAGE 7 UNIT – USE OF DATABASE, A.I. IN MODELLING AND VII SIMULATION Total No of Pages Page 1 of 138 Subject : System Simulation and Modeling Author : Jagat Kumar Paper Code: MCA 504 Vetter : Dr. Pradeep Bhatia Lesson : System Models and System Simulation Lesson No. : 01 Structure 1.0 Objective 1.1 Introduction 1.1.1 Formal Definitions 1.1.2 Brief History of Simulation 1.1.3 Application Area of Simulation 1.1.4 Advantages and Disadvantages of Simulation 1.1.5 Difficulties of Simulation 1.1.6 When to use Simulation? 1.2 Modeling Concepts 1.2.1 System, Model and Events 1.2.2 System State Variables 1.2.2.1 Entities and Attributes 1.2.2.2 Resources 1.2.2.3 List Processing 1.2.2.4 Activities and Delays 1.2.2.5 1.2.3 Model Classifications 1.2.3.1 Discrete-Event Simulation Model 1.2.3.2 Stochastic and Deterministic Systems 1.2.3.3 Static and Dynamic Simulation 1.2.3.4 Discrete vs Continuous Systems 1.2.3.5 An Example 1.3 Computer Workload and Preparation of its Models 1.3.1Steps of the Modeling Process 1.4 Summary 1.5 Key words 1.6 Self Assessment Questions 1.7 References/ Suggested Reading Page 2 of 138 1.0 Objective The main objective of this module to gain the knowledge about system and its behavior so that a person can transform the physical behavior of a system into a mathematical model that can in turn transform into a efficient algorithm for simulation purpose. -

Evidence for the Deterministic Or the Indeterministic Description? a Critique of the Literature About Classical Dynamical Systems

Charlotte Werndl Evidence for the deterministic or the indeterministic description? A critique of the literature about classical dynamical systems Article (Accepted version) (Refereed) Original citation: Werndl, Charlotte (2012) Evidence for the deterministic or the indeterministic description? A critique of the literature about classical dynamical systems. Journal for General Philosophy of Science, 43 (2). pp. 295-312. ISSN 0925-4560 DOI: 10.1007/s10838-012-9199-8 © 2012 Springer Science+Business Media Dordrecht This version available at: http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/47859/ Available in LSE Research Online: April 2014 LSE has developed LSE Research Online so that users may access research output of the School. Copyright © and Moral Rights for the papers on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. Users may download and/or print one copy of any article(s) in LSE Research Online to facilitate their private study or for non-commercial research. You may not engage in further distribution of the material or use it for any profit-making activities or any commercial gain. You may freely distribute the URL (http://eprints.lse.ac.uk) of the LSE Research Online website. This document is the author’s final accepted version of the journal article. There may be differences between this version and the published version. You are advised to consult the publisher’s version if you wish to cite from it. Evidence for the Deterministic or the Indeterministic Description? { A Critique of the Literature about Classical Dynamical Systems Charlotte Werndl, Lecturer, [email protected] Department of Philosophy, Logic and Scientific Method London School of Economics Forthcoming in: Journal for General Philosophy of Science Abstract It can be shown that certain kinds of classical deterministic descrip- tions and indeterministic descriptions are observationally equivalent. -

Introduction to the Random Matrix Theory and the Stochastic Finite Element Method1

Introduction to the Random Matrix Theory and the Stochastic Finite Element Method1 Professor Sondipon Adhikari Chair of Aerospace Engineering, College of Engineering, Swansea University, Swansea UK Email: [email protected], Twitter: @ProfAdhikari Web: http://engweb.swan.ac.uk/˜adhikaris Google Scholar: http://scholar.google.co.uk/citations?user=tKM35S0AAAAJ 1Part of the presented work is taken from MRes thesis by B Pascual: Random Matrix Approach for Stochastic Finite Element Method, 2008, Swansea University Contents 1 Introduction 1 1.1 Randomfielddiscretization ........................... 2 1.1.1 Point discretization methods . 3 1.1.2 Averagediscretizationmethods . 4 1.1.3 Seriesexpansionmethods ........................ 4 1.1.4 Karhunen-Lo`eve expansion (KL expansion) . .. 5 1.2 Response statistics calculation for static problems . ..... 7 1.2.1 Secondmomentapproaches . .. .. 7 1.2.2 Spectral Stochastic Finite Elements Method (SSFEM) . 9 1.3 Response statistics calculation for dynamic problems . .... 11 1.3.1 Randomeigenvalueproblem . 12 1.3.2 High and mid frequency analysis: Non-parametric approach . .. 16 1.3.3 High and mid frequency analysis: Random Matrix Theory . 18 1.4 Summary ..................................... 18 2 Random Matrix Theory (RMT) 20 2.1 Multivariate statistics . 20 2.2 Wishartmatrix .................................. 22 2.3 Fitting of parameter for Wishart distribution . ... 23 2.4 Relationship between dispersion parameter and the correlation length .... 25 2.5 Simulation method for Wishart system matrices . .. 26 2.6 Generalized beta distribution . 28 3 Axial vibration of rods with stochastic properties 30 3.1 Equationofmotion................................ 30 3.2 Deterministic Finite Element model . 31 3.3 Derivation of stiffness matrices . 33 3.4 Derivationofmassmatrices ........................... 34 3.5 Numerical illustrations . -

Deterministic Versus Indeterministic Descriptions: Not That Different After All?

DETERMINISTIC VERSUS INDETERMINISTIC DESCRIPTIONS: NOT THAT DIFFERENT AFTER ALL? CHARLOTTE WERNDL University of Cambridge 1 INTRODUCTION The guiding question of this paper is: can we simulate deterministic de- scriptions by indeterministic descriptions, and conversely? By simulating a deterministic description by an indeterministic one, and conversely, we mean that the deterministic description, when observed, and the indeter- ministic description give the same predictions. Answering this question is a way of finding out how different deter- ministic descriptions are from indeterministic ones. Of course, indetermin- istic descriptions and deterministic descriptions are different in the sense that for the former there is indeterminism in the future evolution and for the latter not. But another way of finding out how different they are is to answer the question whether they give the same predictions; and this ques- tion will concern us. Since the language of deterministic and indeterministic descriptions is mathematics, we will rely on mathematics to answer our guiding ques- tion. In the first place, it is unclear how deterministic and indeterministic descriptions can be compared; this might be one reason for the often-held implicit belief that deterministic and indeterministic descriptions give very different predictions (cf. Weingartner and Schurz 1996, p.203). But we will see that they can often be compared. The deterministic and indeterministic descriptions which we will consider are measure-theoretic deterministic systems and stochastic processes, respectively; they are both ubiquitous in science. To the best of my knowledge, our guiding question has hardly been discussed in philosophy. In this paper I will explain intuitively some mathematical results which show that, from a predictive viewpoint, measure-theoretic determi- nistic systems and stochastic processes are, perhaps surprisingly, very similar. -

A Deterministic Model of the Free Will Phenomenon Abstract

A deterministic model of the free will phenomenon A deterministic model of the free will phenomenon Dr Mark J Hadley Department of Physics, University of Warwick Abstract The abstract concept of indeterministic free will is distinguished from the phenomenon of free will. Evidence for the abstract concept is examined and critically compared with various designs of automata. It is concluded that there is no evidence to support the abstract concept of indeterministic free will, it is inconceivable that a test could be constructed to distinguish an indeterministic agent from a complicated automaton. Testing the free will of an alien visitor is introduced to separate prejudices about who has free will from objective experiments. The phenomenon of free will is modelled with a deterministic decision making agent. The agent values ‘independence’ and satisfies a desire for independence by responding to ‘challenges’. When the agent generates challenges internally it will establish a record of being able to do otherwise. In principle a computer could be built with a free will property. The model also explains false attributions of free will (superstitions). Key words: free will; Determinism; Quantum theory; Predictability; Choice; Automata; A deterministic model of the free will phenomenon 1. Introduction We challenge the evidence for indeterminism and develop a deterministic model of our decision making which makes new predictions. The relation between free will and physics is contentious and puzzling at all levels. Philosophers have debated how free will can be explained with current scientific theories. There is debate about the meaning of the term free will, even leading to questions about whether or not we have anything called free will. -

Asymptotic Analysis of a Deterministic Control System Via Euler's Equation

Journal of Mathematics Research; Vol. 10, No. 1; February 2018 ISSN 1916-9795 E-ISSN 1916-9809 Published by Canadian Center of Science and Education Asymptotic Analysis of a Deterministic Control System via Euler’s Equation Approach Gladys Denisse Salgado Suarez´ 1, Hugo Cruz-Suarez´ 1 & Jose´ Dionicio Zacar´ıas Flores1 1 Facultad de Ciencias F´ısico Matematicas,´ Benemerita´ Universidad Autonoma´ de Puebla, Puebla, Mexico´ Correspondence: Gladys Denisse Salgado Suarez,´ Facultad de Ciencias F´ısico Matematicas,´ Benemerita´ Universidad Autonoma´ de Puebla, Avenida San Claudio y 18 Sur, Colonia San Manuel, Ciudad Universitaria, C.P. 72570, Puebla, Mexico.´ E-mail: [email protected] Received: December 2, 2017 Accepted: December 22, 2017 Online Published: January 18, 2018 doi:10.5539/jmr.v10n1p115 URL: https://doi.org/10.5539/jmr.v10n1p115 Abstract This paper provides necessary conditions in order to guarantee the existence of an unique equilibrium point in a de- terministic control system. Furthermore, under additional conditions, it is proved the convergence of the optimal control sequence to this equilibrium point. The methodology to obtain these statements is based on the Euler’s equation approach. A consumption-investment problem is presented with the objective to illustrate the results exposed. Keywords: Deterministic control systems, Dynamic Programming, equilibrium point, Euler’s equation, stability 1. Introduction In this document a Deterministic Control System (DCS) is considered. A DCS is used to modelling dynamic systems, which are observed in a discrete time by a controller with the purpose that the system performs effectively with respect to certain optimality criteria (objective function). In this way a sequence of strategies to operate the dynamic system is obtained, this sequence is denominated a control policy. -

Are Deterministic Descriptions and Indeterministic Descriptions Observationally Equivalent?

Charlotte Werndl Are deterministic descriptions and indeterministic descriptions observationally equivalent? Article (Accepted version) (Refereed) Original citation: Werndl, Charlotte (2009) Are deterministic descriptions and indeterministic descriptions observationally equivalent? Studies in history and philosophy of science part b: studies in history and philosophy of modern physics, 40 (3). pp. 232-242. ISSN 1355-2198 DOI: http://10.1016/j.shpsb.2009.06.004/ © 2009 Elsevier Ltd This version available at: http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/31094/ Available in LSE Research Online: July 2013 LSE has developed LSE Research Online so that users may access research output of the School. Copyright © and Moral Rights for the papers on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. Users may download and/or print one copy of any article(s) in LSE Research Online to facilitate their private study or for non-commercial research. You may not engage in further distribution of the material or use it for any profit-making activities or any commercial gain. You may freely distribute the URL (http://eprints.lse.ac.uk) of the LSE Research Online website. This document is the author’s final accepted version of the journal article. There may be differences between this version and the published version. You are advised to consult the publisher’s version if you wish to cite from it. Are Deterministic Descriptions And Indeterministic Descriptions Observationally Equivalent? Charlotte Werndl The Queen’s College, Oxford University, [email protected] Forthcoming in: Studies in History and Philosophy of Modern Physics Abstract The central question of this paper is: are deterministic and inde- terministic descriptions observationally equivalent in the sense that they give the same predictions? I tackle this question for measure- theoretic deterministic systems and stochastic processes, both of which are ubiquitous in science. -

A General Classification of Information and Systems M

Oil Shale, 2007, Vol. 24, No. 2 Special ISSN 0208-189X pp. 265–276 © 2007 Estonian Academy Publishers A GENERAL CLASSIFICATION OF INFORMATION AND SYSTEMS ∗ M. VALDMA Department of Electrical Power Engineering Tallinn University of Technology 5 Ehitajate Rd., 19086 Tallinn, Estonia Nowadays the different forms of information are used beginning with deter- ministic information and finishing with fuzzy information. This paper pre- sents a four-level hierarchical classification of information. The first level of hierarchy is deterministic information, the second one – probabilistic information, the third one – uncertain-deterministic and uncertain-pro- babilistic information, and the fourth level is fuzzy-deterministic and fuzzy- probabilistic information. Each following level has to be considered more general than the previous one. The scheme is very simple, but its applications will be immeasurable. An analogical scheme is described for classifying systems and different objects and phenomena. Introduction During its history the humanity has attempted to describe the universe deterministically (concretely and precisely). Scientists have found a lot of deterministic laws, objects and models. Nowadays the overwhelming majority of humanity’s knowledge is a deterministic knowledge. However, besides the deterministic phenomena and objects, there are different non- deterministic phenomena and objects. The majority of phenomena and objects in the complex systems are non-deterministic. Also the information may be deterministic or non-deterministic in many ways. The first step in studying the non-deterministic phenomena was made in the eighteenth century when the probability theory was presented. Nowadays the probability theory and mathematical statistics are powerful tools used for describing and modelling stochastic (random) events, variables, functions, processes and systems.