White and Purple by SATA Ineko

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Authorities Shut Down Local Methamphetamine Operation

THURSDAY, JANUARY 23, 2014 SERVING TILTON, NORTHFIELD, BELMONT & SANBORNTON, N.H. FREE Tilton selectmen consider banning controversial incense products BY DONNA RHODES spread unlabelled abuse of easy for law enforcement, [email protected] the products an “epidem- though. ic,” and in 2012 placed an Cormier said the state TILTON — Det. Nate emergency ban on their laboratory is so backed Buffington and Chief Rob- sale. up that they don’t readily ert Cormier of the Tilton Since then, manufac- have time to test the newer Police Department ap- turers have changed their products to see if they are peared before selectmen formulas from the pre- of the same chemical com- last Thursday evening to vious formula that was pound already banned by propose a town ordinance banned, and it is back on the DEA. COURTESY that would ban the sale of the shelves at many stores. “Spice,” the pair ex- synthetic marijuana, oth- Buffington said the plained to the board, is Forrester salutes new LRBRA president erwise known as “Spice,” newer products are sold also being packaged in Sen. Jeanie Forrester installs Ray Boelig as the 2014 President of Lakes Region Builders & in the town of Tilton. as incense and labeled ways that make it attrac- Remodelers Association at their January meeting. Boelig is the owner of Hampshire Hardwoods. “Spice” comes in pack- that they are not for hu- tive with names such as ets, and is marketed as an man consumption, but law “Scooby Snax,” “Atomic,” incense. Rather than burn- enforcement has seen an and “Klimax” that are tar- ing it as incense, though, increase in problems as geting teens. -

White by Law---Haney Lopez (Abridged Version)

White by Law The Legal Construction of Race Revised and Updated 10th Anniversary Edition Ian Haney Lόpez NEW YORK UNIVERSITY PRESS New York and London (2006) 1│White Lines In its first words on the subject of citizenship, Congress in 1790 restricted naturalization to “white persons.” Though the requirements for naturalization changed frequently thereafter, this racial prerequisite to citizenship endured for over a century and a half, remaining in force until 1952. From the earliest years of this country until just a generation ago, being a “white person” was a condition for acquiring citizenship. Whether one was “white” however, was often no easy question. As immigration reached record highs at the turn of this century, countless people found themselves arguing their racial identity in order to naturalize. From 1907, when the federal government began collecting data on naturalization, until 1920, over one million people gained citizenship under the racially restrictive naturalization laws. Many more sought to naturalize and were rejected. Naturalization rarely involved formal court proceedings and therefore usually generated few if any written records beyond the simple decision. However, a number of cases construing the “white person” prerequisite reached the highest state and federal judicial circles, and two were argued before the U.S. Supreme Court in the early 1920s. These cases produced illuminating published decisions that document the efforts of would-be citizens from around the world to establish their Whiteness at law. Applicants from Hawaii, China, Japan, Burma, and the Philippines, as well as all mixed- race applicants, failed in their arguments. Conversely, courts ruled that applicants from Mexico and Armenia were “white,” but vacillated over the Whiteness of petitioners from Syria, India, and Arabia. -

(You Gotta) Fight for Your Right (To Party!) 3 AM ± Matchbox Twenty. 99 Red Ballons ± Nena

(You Gotta) Fight For Your Right (To Party!) 3 AM ± Matchbox Twenty. 99 Red Ballons ± Nena. Against All Odds ± Phil Collins. Alive and kicking- Simple minds. Almost ± Bowling for soup. Alright ± Supergrass. Always ± Bon Jovi. Ampersand ± Amanda palmer. Angel ± Aerosmith Angel ± Shaggy Asleep ± The Smiths. Bell of Belfast City ± Kristy MacColl. Bitch ± Meredith Brooks. Blue Suede Shoes ± Elvis Presely. Bohemian Rhapsody ± Queen. Born In The USA ± Bruce Springstein. Born to Run ± Bruce Springsteen. Boys Will Be Boys ± The Ordinary Boys. Breath Me ± Sia Brown Eyed Girl ± Van Morrison. Brown Eyes ± Lady Gaga. Chasing Cars ± snow patrol. Chasing pavements ± Adele. Choices ± The Hoosiers. Come on Eileen ± Dexy¶s midnight runners. Crazy ± Aerosmith Crazy ± Gnarles Barkley. Creep ± Radiohead. Cupid ± Sam Cooke. Don¶t Stand So Close to Me ± The Police. Don¶t Speak ± No Doubt. Dr Jones ± Aqua. Dragula ± Rob Zombie. Dreaming of You ± The Coral. Dreams ± The Cranberries. Ever Fallen In Love? ± Buzzcocks Everybody Hurts ± R.E.M. Everybody¶s Fool ± Evanescence. Everywhere I go ± Hollywood undead. Evolution ± Korn. FACK ± Eminem. Faith ± George Micheal. Feathers ± Coheed And Cambria. Firefly ± Breaking Benjamin. Fix Up, Look Sharp ± Dizzie Rascal. Flux ± Bloc Party. Fuck Forever ± Babyshambles. Get on Up ± James Brown. Girl Anachronism ± The Dresden Dolls. Girl You¶ll Be a Woman Soon ± Urge Overkill Go Your Own Way ± Fleetwood Mac. Golden Skans ± Klaxons. Grounds For Divorce ± Elbow. Happy ending ± MIKA. Heartbeats ± Jose Gonzalez. Heartbreak Hotel ± Elvis Presely. Hollywood ± Marina and the diamonds. I don¶t love you ± My Chemical Romance. I Fought The Law ± The Clash. I Got Love ± The King Blues. I miss you ± Blink 182. -

It's Not a Fashion Statement

Gielis /1 MASTER THESIS NORTH AMERICAN STUDIES IT’S NOT A FASHION STATEMENT. AN EXPLORATION OF MASCULINITY AND FEMININITY IN CONTEMPORARY EMO MUSIC. Name of student: Claudia Gielis MA Thesis Advisor: Dr. M. Roza MA Thesis 2nd reader: Prof. Dr. F. Mehring Gielis /2 ENGELSE TAAL EN CULTUUR Teacher who will receive this document: Dr. M. Roza and Prof. Dr. F. Mehring Title of document: It’s Not a Fashion Statement. An exploration of Masculinity and Femininity in Contemporary Emo Music. Name of course: MA Thesis North American Studies Date of submission: 15 August 2018 The work submitted here is the sole responsibility of the undersigned, who has neither committed plagiarism nor colluded in its production. Signed Name of student: Claudia Gielis Gielis /3 Abstract Masculinity and femininity can be performed in many ways. The emo genre explores a variety of ways in which gender can be performed. Theories on gender, masculinity and femininity will be used to analyze both the lyrics and the music videos of these two bands, indicating how they perform gender lyrically and visually. Likewise a short introduction on emo music will be given, to gain a better understanding of the genre and the subculture. It will become clear that the emo subculture allows for men and women to explore their own identity. This is reflected in the music associated to the emo genre as well as their visual representation in their music videos. This essay will explore how both a male fronted band, My Chemical Romance, and a female fronted band, Paramore, perform gender. All studio albums and official music videos will be used to investigate how they have performed gender throughout their career. -

Color Chart Colorchart

Color Chart AMERICANA ACRYLICS Snow (Titanium) White White Wash Cool White Warm White Light Buttermilk Buttermilk Oyster Beige Antique White Desert Sand Bleached Sand Eggshell Pink Chiffon Baby Blush Cotton Candy Electric Pink Poodleskirt Pink Baby Pink Petal Pink Bubblegum Pink Carousel Pink Royal Fuchsia Wild Berry Peony Pink Boysenberry Pink Dragon Fruit Joyful Pink Razzle Berry Berry Cobbler French Mauve Vintage Pink Terra Coral Blush Pink Coral Scarlet Watermelon Slice Cadmium Red Red Alert Cinnamon Drop True Red Calico Red Cherry Red Tuscan Red Berry Red Santa Red Brilliant Red Primary Red Country Red Tomato Red Naphthol Red Oxblood Burgundy Wine Heritage Brick Alizarin Crimson Deep Burgundy Napa Red Rookwood Red Antique Maroon Mulberry Cranberry Wine Natural Buff Sugared Peach White Peach Warm Beige Coral Cloud Cactus Flower Melon Coral Blush Bright Salmon Peaches 'n Cream Coral Shell Tangerine Bright Orange Jack-O'-Lantern Orange Spiced Pumpkin Tangelo Orange Orange Flame Canyon Orange Warm Sunset Cadmium Orange Dried Clay Persimmon Burnt Orange Georgia Clay Banana Cream Sand Pineapple Sunny Day Lemon Yellow Summer Squash Bright Yellow Cadmium Yellow Yellow Light Golden Yellow Primary Yellow Saffron Yellow Moon Yellow Marigold Golden Straw Yellow Ochre Camel True Ochre Antique Gold Antique Gold Deep Citron Green Margarita Chartreuse Yellow Olive Green Yellow Green Matcha Green Wasabi Green Celery Shoot Antique Green Light Sage Light Lime Pistachio Mint Irish Moss Sweet Mint Sage Mint Mint Julep Green Jadeite Glass Green Tree Jade -

ZEN BUDDHISM TODAY -ANNUAL REPORT of the KYOTO ZEN SYMPOSIUM No

Monastic Tradition and Lay Practice from the Perspective of Nantenb6 A Response of Japanese Zen Buddhism to Modernity MICHEL MOHR A !though the political transformations and conflicts that marked the Meiji ..fiRestoration have received much attention, there are still significant gaps in our knowledge of the evolution that affected Japanese Zen Buddhism dur ing the nineteenth century. Simultaneously, from a historical perspective, the current debate about the significance of modernity and modernization shows that the very idea of "modernity" implies often ideologically charged presup positions, which must be taken into account in our review of the Zen Buddhist milieu. Moreover, before we attempt to draw conclusions on the nature of modernization as a whole, it would seem imperative to survey a wider field, especially other religious movements. The purpose of this paper is to provide selected samples of the thought of a Meiji Zen Buddhist leader and to analyze them in terms of the evolution of the Rinzai school from the Tokugawa period to the present. I shall first situ ate Nantenb6 lff:Rtf by looking at his biography, and then examine a reform project he proposed in 1893. This is followed by a considerarion of the nationalist dimension of Nantenb6's thought and his view of lay practice. Owing to space limitations, this study is confined to the example provided by Nantenb6 and his acquaintances and disciples. I must specify that, at this stage, I do not pretend to present new information on this priest. I rely on the published sources, although a lot remains to be done at the level of fun damental research and the gathering of documents. -

“The White/Black Educational Gap, Stalled Progress, and the Long-Term Consequences of the Emergence of Crack Cocaine Markets”

“The White/Black Educational Gap, Stalled Progress, and the Long-Term Consequences of the Emergence of Crack Cocaine Markets” William N. Evans Craig Garthwaite Department of Economics Kellogg School of Management University of Notre Dame Northwestern University 437 Flanner Hall 2001 Sheridan Road Notre Dame, IN 46556 Evanston, IL 60208 vmail: (574) 631 7039 vmail: (202) 746 0990 email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Timothy J. Moore Department of Economics George Washington University 2115 G Street, NW Washington, DC 20052 vmail: (301) 442 1785 email: [email protected] Abstract February 2015 We propose the rise of crack cocaine markets as an explanation for the end to the convergence in black-white educational outcomes in the US that began in the mid-1980s. After constructing a measure to date the arrival of crack markets in cities and states, we show large increases in murder rates after these dates. Black high school completion rates also declined and we estimate that factors associated with crack markets and contemporaneous increases in incarceration rates can account for between 37 and 73 percent of the fall in black male high school completion rates. We argue that the primary mechanism is reduced educational investments in response to decreased returns to schooling. The authors thank Jen Brown, Shawn Bushway, Meghan Busse, Jon Caulkins, Amitabh Chandra, Kerwin Charles, Paul Heaton, Dan Hungerman, Melissa Kearney, Jon Meer, Richard Murnane, Derek Neal, Emily Oster, Rosalie Pacula, Peter Reuter, Bruce Sacerdote, -

Flags and Symbols � � � Gilbert Baker Designed the Rainbow flag for the 1978 San Francisco’S Gay Freedom Celebration

Flags and Symbols ! ! ! Gilbert Baker designed the rainbow flag for the 1978 San Francisco’s Gay Freedom Celebration. In the original eight-color version, pink stood for sexuality, red for life, orange for healing, yellow for the sun, green for nature, turquoise for art, indigo for harmony and violet for the soul.! " Rainbow Flag First unveiled on 12/5/98 the bisexual pride flag was designed by Michael Page. This rectangular flag consists of a broad magenta stripe at the top (representing same-gender attraction,) a broad stripe in blue at the bottoms (representing opposite- gender attractions), and a narrower deep lavender " band occupying the central fifth (which represents Bisexual Flag attraction toward both genders). The pansexual pride flag holds the colors pink, yellow and blue. The pink band symbolizes women, the blue men, and the yellow those of a non-binary gender, such as a gender bigender or gender fluid Pansexual Flag In August, 2010, after a process of getting the word out beyond the Asexual Visibility and Education Network (AVEN) and to non-English speaking areas, a flag was chosen following a vote. The black stripe represents asexuality, the grey stripe the grey-are between sexual and asexual, the white " stripe sexuality, and the purple stripe community. Asexual Flag The Transgender Pride flag was designed by Monica Helms. It was first shown at a pride parade in Phoenix, Arizona, USA in 2000. The flag represents the transgender community and consists of five horizontal stripes. Two light blue which is the traditional color for baby boys, two pink " for girls, with a white stripe in the center for those Transgender Flag who are transitioning, who feel they have a neutral gender or no gender, and those who are intersex. -

Alma M. Karlin's Visits to Temples and Shrines in Japan

ALMA M. KARLIN’S VISITS TO TEMPLES AND SHRINES IN JAPAN Chikako Shigemori Bučar Introduction Alma M. Karlin (1889-1950), born in Celje, went on a journey around the world between 1919 and 1928, and stayed in Japan for a lit- tle more than a year, from June 1922 to July 1923. There is a large col- lection of postcards from her journey archived in the Regional Museum of Celje. Among them are quite a number of postcards from Japan (528 pieces), and among these, about 100 of temples and shrines, including tombs of emperors and other historical persons - i.e., postcards related to religions and folk traditions of Japan. Karlin almost always wrote on the reverse of these postcards some lines of explanation about each picture in German. On the other hand, the Japanese part of her trav- elogue is very short, only about 40 pages of 700. (Einsame Weltreise / Im Banne der Südsee, both published in Germany in 1930). In order to understand Alma Karlin’s observation and interpretation of matters related to religions in Japan and beliefs of Japanese people, we depend on her memos on the postcards and her rather subjective impressions in her travelogue. This paper presents facts on the religious sights which Karlin is thought to have visited, and an analysis of Karlin’s understand- ing and interpretation of the Japanese religious life based on her memos on the postcards and the Japanese part of her travelogue. In the following section, Alma Karlin and her journey around the world are briefly presented, with a specific focus on the year of her stay in Japan, 1922-1923. -

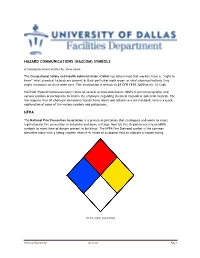

Hazard Communications (Hazcom) Symbols Nfpa

HAZARD COMMUNICATIONS (HAZCOM) SYMBOLS A training document written by: Steve Serna The Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) has determined that workers have a, “right to know” what chemical hazards are present in their particular work areas, or what chemical hazards they might encounter on their work sites. This information is written in 29 CFR 1910.1200 of the US Code. HAZCOM (Hazard Communications) relies on several written documents (MSDS & written programs) and various symbols or pictograms to inform the employee regarding chemical hazards or potential hazards. The law requires that all chemical containers/vessels have labels and adhere to a set standard; here is a quick explanation of some of the various symbols and pictograms… NFPA The National Fire Prevention Association is a private organization that catalogues and works to enact legislation for fire prevention in industrial and home settings. Most US Fire Departments rely on NFPA symbols to warn them of danger present in buildings. The NFPA Fire Diamond symbol is the common identifier along with a rating number (from 0-4) inside of a colored field to indicate a hazard rating. NFPA FIRE DIAMOND Hazcommadesimple.doc Opr: Serna Page 1 HAZARD RATINGS GUIDE For example: Diesel Fuel has an NFPA hazard rating of 0-2-0. 0 for Health (blue), 2 for Flammability (red), and 0 for Instability/Reactivity (yellow). HMIS (taken from WIKIPEDIA) The Hazardous Materials Identification System (HMIS) is a numerical hazard rating that incorporates the use of labels with color-coded bars as well as training materials. It was developed by the American Paints & Coatings Association as a compliance aid for the OSHA Hazard Communication Standard. -

R Color Cheatsheet

R Color Palettes R color cheatsheet This is for all of you who don’t know anything Finding a good color scheme for presenting data about color theory, and don’t care but want can be challenging. This color cheatsheet will help! some nice colors on your map or figure….NOW! R uses hexadecimal to represent colors TIP: When it comes to selecting a color palette, Hexadecimal is a base-16 number system used to describe DO NOT try to handpick individual colors! You will color. Red, green, and blue are each represented by two characters (#rrggbb). Each character has 16 possible waste a lot of time and the result will probably not symbols: 0,1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,A,B,C,D,E,F: be all that great. R has some good packages for color palettes. Here are some of the options “00” can be interpreted as 0.0 and “FF” as 1.0 Packages: grDevices and i.e., red= #FF0000 , black=#000000, white = #FFFFFF grDevices colorRamps palettes Two additional characters (with the same scale) can be grDevices comes with the base cm.colors added to the end to describe transparency (#rrggbbaa) installation and colorRamps topo.colors terrain.colors R has 657 built in color names Example: must be installed. Each palette’s heat.colors To see a list of names: function has an argument for rainbow colors() peachpuff4 the number of colors and see P. 4 for These colors are displayed on P. 3. transparency (alpha): options R translates various color models to hex, e.g.: heat.colors(4, alpha=1) • RGB (red, green, blue): The default intensity scale in R > #FF0000FF" "#FF8000FF" "#FFFF00FF" "#FFFF80FF“ ranges from 0-1; but another commonly used scale is 0- 255. -

Fruit and Vegetable Color Chart Red Orange/ Yellow Green Blue

Fruit and Vegetable Color Chart Color Why It’s Good For You Fruit and Veggie Examples • Lycopene: • Reduces risk of prostate cancer tomatoes, watermelon, red cabbage, red • Reduces risk of hypertension bell peppers • Decreases LDL (bad) cholesterol levels • Quercetin • Decreases plaque formation apples, cherries, cranberries, red onions, Red • Reduces risk of lung and breast cancers beets • Improves aerobic endurance capacity • Anthocyanins • Reduces risk of heart disease red raspberries, sweet cherries, • Improves brain function and memory strawberries, cranberries, beets, red apples, • Improves balance kidney beans • Improves vision • Beta Carotene/Vitamin A Carrots, pumpkins, sweet potatoes, • Improves eye health cantaloupes, apricots, peaches, papaya, Reduces risk of cancer and heart disease Orange / • grapefruits, persimmons, butternut squash • Helps to fight infection Yellow • Bioflavonoids oranges, grapefruit, lemons, tangerines, • Reduces risk of heart disease clementines, peaches, papaya, apricots, • Improves brain function nectarines, pineapple • Beta Carotene/Vitamin A kale, spinach, lettuce, mustard greens, • Keeps eyes healthy cabbage, swiss chard, collard greens, • Reduces risk of cancer and heart disease parsley, basil, beet greens, endive, chives, • Helps to fight infections arugula, asparagus • Folate • Reduces risk of birth defects spinach, endive, lettuce, asparagus, • Protection against neurodegenerative mustard greens, green beans, collard disorders greens, okra, broccoli Green • Helps to fight infections • Regulates