How Does Dinosaur Diversity Through Time Change Through Time?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Implications for Predatory Dinosaur Macroecology and Ontogeny in Later Late Cretaceous Asiamerica

Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences Theropod Guild Structure and the Tyrannosaurid Niche Assimilation Hypothesis: Implications for Predatory Dinosaur Macroecology and Ontogeny in later Late Cretaceous Asiamerica Journal: Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences Manuscript ID cjes-2020-0174.R1 Manuscript Type: Article Date Submitted by the 04-Jan-2021 Author: Complete List of Authors: Holtz, Thomas; University of Maryland at College Park, Department of Geology; NationalDraft Museum of Natural History, Department of Geology Keyword: Dinosaur, Ontogeny, Theropod, Paleocology, Mesozoic, Tyrannosauridae Is the invited manuscript for consideration in a Special Tribute to Dale Russell Issue? : © The Author(s) or their Institution(s) Page 1 of 91 Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences 1 Theropod Guild Structure and the Tyrannosaurid Niche Assimilation Hypothesis: 2 Implications for Predatory Dinosaur Macroecology and Ontogeny in later Late Cretaceous 3 Asiamerica 4 5 6 Thomas R. Holtz, Jr. 7 8 Department of Geology, University of Maryland, College Park, MD 20742 USA 9 Department of Paleobiology, National Museum of Natural History, Washington, DC 20013 USA 10 Email address: [email protected] 11 ORCID: 0000-0002-2906-4900 Draft 12 13 Thomas R. Holtz, Jr. 14 Department of Geology 15 8000 Regents Drive 16 University of Maryland 17 College Park, MD 20742 18 USA 19 Phone: 1-301-405-4084 20 Fax: 1-301-314-9661 21 Email address: [email protected] 22 23 1 © The Author(s) or their Institution(s) Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences Page 2 of 91 24 ABSTRACT 25 Well-sampled dinosaur communities from the Jurassic through the early Late Cretaceous show 26 greater taxonomic diversity among larger (>50kg) theropod taxa than communities of the 27 Campano-Maastrichtian, particularly to those of eastern/central Asia and Laramidia. -

Age and Paleoenvironment of the Maastrichtian to Paleocene of the Mahajanga Basin, Madagascar: a Multidisciplinary Approach

Marine Micropaleontology 47 (2002) 17^70 www.elsevier.com/locate/marmicro Age and paleoenvironment of the Maastrichtian to Paleocene of the Mahajanga Basin, Madagascar: a multidisciplinary approach S. Abramovich a;Ã, G. Keller a, T. Adatte b, W. Stinnesbeck c, L. Hottinger d, D. Stueben e, Z. Berner e, B. Ramanivosoa f , A. Randriamanantenasoa g a Department of Geosciences, Princeton University, Princeton, NJ 08544, USA b Geological Institute, University of Neucha“tel, CH-2007 Neucha“tel, Switzerland c Geological Institute, University of Karlsruhe, D-76128 Karlsruhe, Germany d Museum of Natural History, CH-4001 Basel, Switzerland e Petrography and Geochemistry Institute, University of Karlsruhe, D-76128 Karlsruhe, Germany f Muse¤e Akiba, PO Box 652, Mahajanga 401, Madagascar g De¤partment des Sciences de la Terre, Universite¤ de Mahajanga, Mahajanga, Madagascar Received 30 May 2001; received in revised form 1 May 2002; accepted 8 May 2002 Abstract Lithology, geochemistry, stable isotopes and integrated high-resolution biostratigraphy of the Berivotra and Amboanio sections provide new insights into the age, faunal turnovers, climate, sea level and environmental changes of the Maastrichtian to early Paleocene of the Mahajanga Basin of Madagascar. In the Berivotra type area, the dinosaur-rich fluvial lowland sediments of the Anembalemba Member prevailed into the earliest Maastrichtian. These are overlain by marginal marine and near-shore clastics that deepen upwards to hemipelagic middle neritic marls by 69.6 Ma, accompanied by arid to seasonally cool temperate climates through the early and late Maastrichtian. An unconformity between the Berivotra Formation and Betsiboka limestone marks the K^Tboundary, and juxtaposes early Danian (zone Plc? or Pld) and latest Maastrichtian (zones CF2^CF1, Micula prinsii) sediments. -

Late Cretaceous Sea Surface Temperature Record

Discussion Paper | Discussion Paper | Discussion Paper | Discussion Paper | Clim. Past Discuss., 11, 5049–5071, 2015 www.clim-past-discuss.net/11/5049/2015/ doi:10.5194/cpd-11-5049-2015 CPD © Author(s) 2015. CC Attribution 3.0 License. 11, 5049–5071, 2015 This discussion paper is/has been under review for the journal Climate of the Past (CP). Late Cretaceous sea Please refer to the corresponding final paper in CP if available. surface temperature record Late Cretaceous (Late Campanian– N. Thibault et al. Maastrichtian) sea surface temperature record of the Boreal Chalk Sea Title Page Abstract Introduction N. Thibault1, R. Harlou1, N. H. Schovsbo2, L. Stemmerik3, and F. Surlyk1 Conclusions References 1Department of Geosciences and Natural Resource Management, University of Copenhagen, Øster Voldgade 10, 1350 Copenhagen K, Denmark Tables Figures 2Geological Survey of Denmark and Greenland, Øster Voldgade 10, 1350 Copenhagen K, Denmark J I 3Statens Naturhistoriske Museum, University of Copenhagen, Øster Voldgade 5–7, 1350 Copenhagen K, Denmark J I Back Close Received: 26 September 2015 – Accepted: 16 October 2015 – Published: 3 November 2015 Correspondence to: N. Thibault ([email protected]) Full Screen / Esc Published by Copernicus Publications on behalf of the European Geosciences Union. Printer-friendly Version Interactive Discussion 5049 Discussion Paper | Discussion Paper | Discussion Paper | Discussion Paper | Abstract CPD The last 8 Myr of the Cretaceous greenhouse interval were characterized by a pro- gressive global cooling with superimposed cool/warm fluctuations. The mechanisms 11, 5049–5071, 2015 responsible for these climatic fluctuations remain a source of debate that can only 5 be resolved through multi-disciplinary studies and better time constraints. -

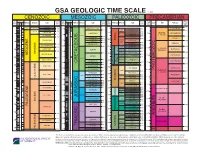

GEOLOGIC TIME SCALE V

GSA GEOLOGIC TIME SCALE v. 4.0 CENOZOIC MESOZOIC PALEOZOIC PRECAMBRIAN MAGNETIC MAGNETIC BDY. AGE POLARITY PICKS AGE POLARITY PICKS AGE PICKS AGE . N PERIOD EPOCH AGE PERIOD EPOCH AGE PERIOD EPOCH AGE EON ERA PERIOD AGES (Ma) (Ma) (Ma) (Ma) (Ma) (Ma) (Ma) HIST HIST. ANOM. (Ma) ANOM. CHRON. CHRO HOLOCENE 1 C1 QUATER- 0.01 30 C30 66.0 541 CALABRIAN NARY PLEISTOCENE* 1.8 31 C31 MAASTRICHTIAN 252 2 C2 GELASIAN 70 CHANGHSINGIAN EDIACARAN 2.6 Lopin- 254 32 C32 72.1 635 2A C2A PIACENZIAN WUCHIAPINGIAN PLIOCENE 3.6 gian 33 260 260 3 ZANCLEAN CAPITANIAN NEOPRO- 5 C3 CAMPANIAN Guada- 265 750 CRYOGENIAN 5.3 80 C33 WORDIAN TEROZOIC 3A MESSINIAN LATE lupian 269 C3A 83.6 ROADIAN 272 850 7.2 SANTONIAN 4 KUNGURIAN C4 86.3 279 TONIAN CONIACIAN 280 4A Cisura- C4A TORTONIAN 90 89.8 1000 1000 PERMIAN ARTINSKIAN 10 5 TURONIAN lian C5 93.9 290 SAKMARIAN STENIAN 11.6 CENOMANIAN 296 SERRAVALLIAN 34 C34 ASSELIAN 299 5A 100 100 300 GZHELIAN 1200 C5A 13.8 LATE 304 KASIMOVIAN 307 1250 MESOPRO- 15 LANGHIAN ECTASIAN 5B C5B ALBIAN MIDDLE MOSCOVIAN 16.0 TEROZOIC 5C C5C 110 VANIAN 315 PENNSYL- 1400 EARLY 5D C5D MIOCENE 113 320 BASHKIRIAN 323 5E C5E NEOGENE BURDIGALIAN SERPUKHOVIAN 1500 CALYMMIAN 6 C6 APTIAN LATE 20 120 331 6A C6A 20.4 EARLY 1600 M0r 126 6B C6B AQUITANIAN M1 340 MIDDLE VISEAN MISSIS- M3 BARREMIAN SIPPIAN STATHERIAN C6C 23.0 6C 130 M5 CRETACEOUS 131 347 1750 HAUTERIVIAN 7 C7 CARBONIFEROUS EARLY TOURNAISIAN 1800 M10 134 25 7A C7A 359 8 C8 CHATTIAN VALANGINIAN M12 360 140 M14 139 FAMENNIAN OROSIRIAN 9 C9 M16 28.1 M18 BERRIASIAN 2000 PROTEROZOIC 10 C10 LATE -

A Census of Dinosaur Fossils Recovered from the Hell Creek and Lance Formations (Maastrichtian)

The Journal of Paleontological Sciences: JPS.C.2019.01 1 TAKING COUNT: A Census of Dinosaur Fossils Recovered From the Hell Creek and Lance Formations (Maastrichtian). ______________________________________________________________________________________ Walter W. Stein- President, PaleoAdventures 1432 Mill St.. Belle Fourche, SD 57717. [email protected] 605-210-1275 ABSTRACT: A census of Hell Creek and Lance Formation dinosaur remains was conducted from April, 2017 through February of 2018. Online databases were reviewed and curators and collections managers interviewed in an effort to determine how much material had been collected over the past 130+ years of exploration. The results of this new census has led to numerous observations regarding the quantity, quality, and locations of the total collection, as well as ancillary data on the faunal diversity and density of Late Cretaceous dinosaur populations. By reviewing the available data, it was also possible to make general observations regarding the current state of certain exploration programs, the nature of collection bias present in those collections and the availability of today's online databases. A total of 653 distinct, associated and/or articulated remains (skulls and partial skeletons) were located. Ceratopsid skulls and partial skeletons (mostly identified as Triceratops) were the most numerous, tallying over 335+ specimens. Hadrosaurids (Edmontosaurus) were second with at least 149 associated and/or articulated remains. Tyrannosaurids (Tyrannosaurus and Nanotyrannus) were third with a total of 71 associated and/or articulated specimens currently known to exist. Basal ornithopods (Thescelosaurus) were also well represented by at least 42 known associated and/or articulated remains. The remaining associated and/or articulated specimens, included pachycephalosaurids (18), ankylosaurids (6) nodosaurids (6), ornithomimids (13), oviraptorosaurids (9), dromaeosaurids (1) and troodontids (1). -

Report 2015–1087

Chronostratigraphic Cross Section of Cretaceous Formations in Western Montana, Western Wyoming, Eastern Utah, Northeastern Arizona, and Northwestern New Mexico, U.S.A. Pamphlet to accompany Open-File Report 2015–1087 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey Chronostratigraphic Cross Section of Cretaceous Formations in Western Montana, Western Wyoming, Eastern Utah, Northeastern Arizona, and Northwestern New Mexico, U.S.A. By E.A. Merewether and K.C. McKinney Pamphlet to accompany Open-File Report 2015–1087 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior SALLY JEWELL, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey Suzette M. Kimball, Acting Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia: 2015 For more information on the USGS—the Federal source for science about the Earth, its natural and living resources, natural hazards, and the environment—visit http://www.usgs.gov or call 1–888–ASK–USGS. For an overview of USGS information products, including maps, imagery, and publications, visit http://www.usgs.gov/pubprod/. Any use of trade, firm, or product names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. Although this information product, for the most part, is in the public domain, it also may contain copyrighted materials as noted in the text. Permission to reproduce copyrighted items must be secured from the copyright owner. Suggested citation: Merewether, E.A., and McKinney, K.C., 2015, Chronostratigraphic cross section of Cretaceous formations in western Montana, western Wyoming, eastern Utah, northeastern Arizona, and northwestern New Mexico, U.S.A.: U.S. Geological Survey Open-File Report 2015–1087, 10 p. -

A New Middle Jurassic Diplodocoid Suggests an Earlier Dispersal and Diversification of Sauropod Dinosaurs

ARTICLE DOI: 10.1038/s41467-018-05128-1 OPEN A new Middle Jurassic diplodocoid suggests an earlier dispersal and diversification of sauropod dinosaurs Xing Xu1, Paul Upchurch2, Philip D. Mannion 3, Paul M. Barrett 4, Omar R. Regalado-Fernandez 2, Jinyou Mo5, Jinfu Ma6 & Hongan Liu7 1234567890():,; The fragmentation of the supercontinent Pangaea has been suggested to have had a profound impact on Mesozoic terrestrial vertebrate distributions. One current paradigm is that geo- graphic isolation produced an endemic biota in East Asia during the Jurassic, while simul- taneously preventing diplodocoid sauropod dinosaurs and several other tetrapod groups from reaching this region. Here we report the discovery of the earliest diplodocoid, and the first from East Asia, to our knowledge, based on fossil material comprising multiple individuals and most parts of the skeleton of an early Middle Jurassic dicraeosaurid. The new discovery challenges conventional biogeographical ideas, and suggests that dispersal into East Asia occurred much earlier than expected. Moreover, the age of this new taxon indicates that many advanced sauropod lineages originated at least 15 million years earlier than previously realised, achieving a global distribution while Pangaea was still a coherent landmass. 1 Key Laboratory of Evolutionary Systematics of Vertebrates, Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology & Paleoanthropology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, 100044 Beijing, China. 2 Department of Earth Sciences, University College London, Gower Street, London WC1E 6BT, UK. 3 Department of Earth Science and Engineering, Imperial College London, South Kensington Campus, London SW7 2AZ, UK. 4 Department of Earth Sciences, Natural History Museum, Cromwell Road, London SW7 5BD, UK. 5 Natural History Museum of Guangxi, 530012 Nanning, Guangxi, China. -

Dinosaur Morphological Diversity and the End-Cretaceous Extinction

ARTICLE Received 24 Feb 2012 | Accepted 30 Mar 2012 | Published 1 May 2012 DOI: 10.1038/ncomms1815 Dinosaur morphological diversity and the end-Cretaceous extinction Stephen L. Brusatte1,2, Richard J. Butler3,4, Albert Prieto-Márquez4 & Mark A. Norell1 The extinction of non-avian dinosaurs 65 million years ago is a perpetual topic of fascination, and lasting debate has focused on whether dinosaur biodiversity was in decline before end- Cretaceous volcanism and bolide impact. Here we calculate the morphological disparity (anatomical variability) exhibited by seven major dinosaur subgroups during the latest Cretaceous, at both global and regional scales. Our results demonstrate both geographic and clade-specific heterogeneity. Large-bodied bulk-feeding herbivores (ceratopsids and hadrosauroids) and some North American taxa declined in disparity during the final two stages of the Cretaceous, whereas carnivorous dinosaurs, mid-sized herbivores, and some Asian taxa did not. Late Cretaceous dinosaur evolution, therefore, was complex: there was no universal biodiversity trend and the intensively studied North American record may reveal primarily local patterns. At least some dinosaur groups, however, did endure long-term declines in morphological variability before their extinction. 1 Division of Paleontology, American Museum of Natural History, Central Park West at 79th Street, New York, New York 10024 USA. 2 Department of Earth and Environmental Sciences, Columbia University, New York, New York 10025 USA. 3 GeoBio-Center, Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München, Richard- Wagner-Straße 10, Munich D-80333, Germany. 4 Bayerische Staatssammlung für Paläontologie und Geologie, Richard-Wagner-Straße 10, Munich D- 80333, Germany. Correspondence and requests for materials should be addressed to S.L.B. -

Offshore Marine Actinopterygian Assemblages from the Maastrichtian–Paleogene of the Pindos Unit in Eurytania, Greece

Offshore marine actinopterygian assemblages from the Maastrichtian–Paleogene of the Pindos Unit in Eurytania, Greece Thodoris Argyriou1 and Donald Davesne2,3 1 UMR 7207 (MNHN—Sorbonne Université—CNRS) Centre de Recherche en Paléontologie, Museum National d’Histoire naturelle, Paris, France 2 Department of Earth Sciences, University of Oxford, Oxford, UK 3 UMR 7205 (MNHN—Sorbonne Université—CNRS—EPHE), Institut de Systématique, Évolution, Biodiversité, Museum National d’Histoire naturelle, Paris, France ABSTRACT The fossil record of marine ray-finned fishes (Actinopterygii) from the time interval surrounding the Cretaceous–Paleogene (K–Pg) extinction is scarce at a global scale, hampering our understanding of the impact, patterns and processes of extinction and recovery in the marine realm, and its role in the evolution of modern marine ichthyofaunas. Recent fieldwork in the K–Pg interval of the Pindos Unit in Eurytania, continental Greece, shed new light on forgotten fossil assemblages and allowed for the collection of a diverse, but fragmentary sample of actinopterygians from both late Maastrichtian and Paleocene rocks. Late Maastrichtian assemblages are dominated by Aulopiformes (†Ichthyotringidae, †Enchodontidae), while †Dercetidae (also Aulopiformes), elopomorphs and additional, unidentified teleosts form minor components. Paleocene fossils include a clupeid, a stomiiform and some unidentified teleost remains. This study expands the poor record of body fossils from this critical time interval, especially for smaller sized taxa, while providing a rare, paleogeographically constrained, qualitative glimpse of open-water Tethyan ecosystems from both before and after the extinction event. Faunal similarities Submitted 21 September 2020 Accepted 9 December 2020 between the Maastrichtian of Eurytania and older Late Cretaceous faunas reveal a Published 20 January 2021 higher taxonomic continuum in offshore actinopterygian faunas and ecosystems Corresponding author spanning the entire Late Cretaceous of the Tethys. -

How Has Our Knowledge of Dinosaur Diversity Through Geologic Time Changed Through Research History?

How has our knowledge of dinosaur diversity through geologic time changed through research history? Jonathan P. Tennant1, Alfio Alessandro Chiarenza1 and Matthew Baron2,3 1 Department of Earth Science and Engineering, Imperial College London, London, UK 2 Department of Earth Science, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, UK 3 Earth Sciences Department, Natural History Museum, London, UK ABSTRACT Assessments of dinosaur macroevolution at any given time can be biased by the historical publication record. Recent studies have analysed patterns in dinosaur diversity that are based on secular variations in the numbers of published taxa. Many of these have employed a range of approaches that account for changes in the shape of the taxonomic abundance curve, which are largely dependent on databases compiled from the primary published literature. However, how these ‘corrected’ diversity patterns are influenced by the history of publication remains largely unknown. Here, we investigate the influence of publication history between 1991 and 2015 on our understanding of dinosaur evolution using raw diversity estimates and shareholder quorum subsampling for the three major subgroups: Ornithischia, Sauropodomorpha, and Theropoda. We find that, while sampling generally improves through time, there remain periods and regions in dinosaur evolutionary history where diversity estimates are highly volatile (e.g. the latest Jurassic of Europe, the mid-Cretaceous of North America, and the Late Cretaceous of South America). Our results show that historical changes in database compilation can often Submitted 24 May 2017 substantially influence our interpretations of dinosaur diversity. ‘Global’ estimates Accepted 6 February 2018 of diversity based on the fossil record are often also based on incomplete, and Published 19 February 2018 distinct regional signals, each subject to their own sampling history. -

CHRISTOPHER THOMAS GRIFFIN DEPARTMENT of EARTH and PLANETARY SCIENCES Yale University 210 Whitney Ave

Christopher Griffin 1 Curriculum Vitae CHRISTOPHER THOMAS GRIFFIN DEPARTMENT OF EARTH AND PLANETARY SCIENCES Yale University 210 Whitney Ave. New Haven CT 06511 Phone: +1 (530) 217-9516 E-mail: [email protected] www.ctgriffin.wixsite.com/site Current Position Postdoctoral Associate (July 2020–present) Yale University, Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences Education Virginia Tech, Blacksburg, VA, USA Ph.D. in Geosciences (2020) M.S. in Geosciences (2016) Cedarville University, Cedarville, OH, USA B.S. in Biology, Geology, and Molecular & Cellular Biology, with highest honor (2014) External Grants and Fellowships Total amount of competitive funding offered: $618,382.74 (USD) Total amount of competitive funding received: $364,442 (USD) 2020 COVID-19 Grant Support National Geographic Society, $3,350 (co-principal investigator) Postdoctoral Research Fellowship in Biology (NSF PRFB) National Science Foundation, $138,000. Marie Skłodowska-Curie Actions Individual Fellowship European Commission Research Executive Agency, 212,933.76 €. Review score 98.20/100. Declined. 2019 Arthur J. Boucot Student Research Award Paleontological Society, $1,200 Jackson School of Geosciences Student Travel Grant Society of Vertebrate Paleontology, $600 Young Researcher Travel Grant for Evolutionary Developmental Biology Developmental Dynamics, $500 2018 Exploration Grant National Geographic Society, $27,390 (co-principal investigator) 2017 Graduate Student Research Grant Geological Society of America, $1,755 Early Career Grant National Geographic Society, -

The End of the Sauropod Dinosaur Hiatus in North America

Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 297 (2010) 486–490 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/palaeo The end of the sauropod dinosaur hiatus in North America Michael D. D'Emic a,⁎, Jeffrey A. Wilson a, Richard Thompson b a Museum of Paleontology and Department of Geological Sciences, University of Michigan, 1109 Geddes Avenue, Ann Arbor, MI 48109–1079, USA b Department of Geosciences, University of Arizona, 1040 E 4th St, Tucson, AZ, 85721-0077, USA article info abstract Article history: Sauropod dinosaurs reached their acme in abundance and diversity in North America during the Late Received 4 February 2010 Jurassic. Persisting in lesser numbers into the Early Cretaceous, sauropods disappeared from the North Received in revised form 16 August 2010 American fossil record from the Cenomanian until the Campanian or Maastrichtian stage of the Late Accepted 30 August 2010 Cretaceous. This ca. 25–30 million-year long sauropod hiatus has been attributed to either a true extinction, Available online 19 September 2010 perhaps due to competition with ornithischian dinosaurs, or a false extinction, due to non-preservation of sediments bearing sauropods. The duration of the sauropod hiatus remains in question due to uncertainty in Keywords: fi Dinosaur the ages and af nities of the specimens bounding the observed gap. In this paper, we re-examine the Sauropod phylogenetic affinity of materials from Campanian-aged sediments of Adobe Canyon, Arizona that currently Titanosaur mark the end of the sauropod hiatus. Based on the original description of those remains and new specimens Alamosaurus from the same formation, we conclude that the Adobe Canyon vertebrae do not pertain to titanosaurs, but to Hadrosaur hadrosaurid dinosaurs.