Holistically Understanding and Enhancing the Adaptation of Remote High-Mountain Communities to Hydrometeorological Extremes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

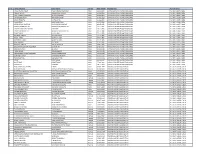

Complete List of Books in Library Acc No Author Title of Book Subject Publisher Year R.No

Complete List of Books in Library Acc No Author Title of book Subject Publisher Year R.No. 1 Satkari Mookerjee The Jaina Philosophy of PHIL Bharat Jaina Parisat 8/A1 Non-Absolutism 3 Swami Nikilananda Ramakrishna PER/BIO Rider & Co. 17/B2 4 Selwyn Gurney Champion Readings From World ECO `Watts & Co., London 14/B2 & Dorothy Short Religion 6 Bhupendra Datta Swami Vivekananda PER/BIO Nababharat Pub., 17/A3 Calcutta 7 H.D. Lewis The Principal Upanisads PHIL George Allen & Unwin 8/A1 14 Jawaherlal Nehru Buddhist Texts PHIL Bruno Cassirer 8/A1 15 Bhagwat Saran Women In Rgveda PHIL Nada Kishore & Bros., 8/A1 Benares. 15 Bhagwat Saran Upadhya Women in Rgveda LIT 9/B1 16 A.P. Karmarkar The Religions of India PHIL Mira Publishing Lonavla 8/A1 House 17 Shri Krishna Menon Atma-Darshan PHIL Sri Vidya Samiti 8/A1 Atmananda 20 Henri de Lubac S.J. Aspects of Budhism PHIL sheed & ward 8/A1 21 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad Bhagabatam PHIL Dhirendra Nath Bose 8/A2 22 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam VolI 23 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam Vo.l III 24 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad Bhagabatam PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 25 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam Vol.V 26 Mahadev Desai The Gospel of Selfless G/REL Navijvan Press 14/B2 Action 28 Shankar Shankar's Children Art FIC/NOV Yamuna Shankar 2/A2 Number Volume 28 29 Nil The Adyar Library Bulletin LIT The Adyar Library and 9/B2 Research Centre 30 Fraser & Edwards Life And Teaching of PER/BIO Christian Literature 17/A3 Tukaram Society for India 40 Monier Williams Hinduism PHIL Susil Gupta (India) Ltd. -

Sl. No. Name of Players Father Name Gender Date of Birth Member Unit

Sl. No. Name of Players Father Name Gender Date of Birth Member Unit PLAYER ID NO 1 VIKAS VISHNU PILLAY PILLAY VISHNU MANIKAM Male 20.11.1989 AIR INDIA SPORTS PROMOTION BOARD PL / AIR / 00042 / 2013 2 YOUSUF AFFAN MOHAMMED YOUSUF Male 29.12.1994 AIR INDIA SPORTS PROMOTION BOARD PL / AIR / 00081 / 2013 3 LALIT KUMAR UPADHYAY SATISH UPADHYAY Male 01.12.1993 AIR INDIA SPORTS PROMOTION BOARD PL / AIR / 00090 / 2013 4 SHIVENDRA SINGH JHAMMAN SINGH Male 09.06.1983 AIR INDIA SPORTS PROMOTION BOARD PL / AIR / 01984 / 2014 5 ARJUN HALAPPA B K HALAPPA Male 17.12.1980 AIR INDIA SPORTS PROMOTION BOARD PL / AIR / 01985 / 2014 6 JOGA SINGH HARJINDER SINGH Male 01.01.1986 AIR INDIA SPORTS PROMOTION BOARD PL / AIR / 01986 / 2014 7 GIRISH RAVAJI PIMPALE RAVAJI BHIKU PIMPALE Male 06.05.1983 AIR INDIA SPORTS PROMOTION BOARD PL / AIR / 01987 / 2014 8 VIKRAM VISHNU PILLAY MANIKAM VISHNU PILLAY Male 27.11.1981 AIR INDIA SPORTS PROMOTION BOARD PL / AIR / 01988 / 2014 9 VINAYA VAKKALIGA SWAMY B SWAMY Male 24.11.1985 AIR INDIA SPORTS PROMOTION BOARD PL / AIR / 01989 / 2014 10 VINOD VISHNU PILLAY MANIKAM VISHNU PILLAY Male 05.12.1988 AIR INDIA SPORTS PROMOTION BOARD PL / AIR / 01990 / 2014 11 SAMEER DAD KHUDA DAD Male 25.11.1978 AIR INDIA SPORTS PROMOTION BOARD PL / AIR / 01991 / 2014 12 PRABODH TIRKEY WALTER TIREKY Male 15.12.1985 AIR INDIA SPORTS PROMOTION BOARD PL / AIR / 01992 / 2014 13 BIMAL LAKRA MARCUS LAKRA Male 04.05.1980 AIR INDIA SPORTS PROMOTION BOARD PL / AIR / 01993 / 2014 14 BIRENDAR LAKRA MARCUS LAKRA Male 22.12.1985 AIR INDIA SPORTS PROMOTION BOARD -

(Ìž'í'ˆìœ¼ë¡Œ) ˪…˶€ : ̦ʲ¨ Ì°¾Ê¸°Ì—͈¬Í'œ

P. Vasu ì˜í ™” 명부 (작품으로) Sethupathi IPS https://ko.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/sethupathi-ips-3644978/actors Pillaikkaga https://ko.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/pillaikkaga-12932045/actors Kathanayakudu https://ko.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/kathanayakudu-16250236/actors Malabar Police https://ko.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/malabar-police-6740755/actors Rickshaw Mama https://ko.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/rickshaw-mama-7332000/actors Udan Pirappu https://ko.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/udan-pirappu-16254909/actors Mr. Madras https://ko.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/mr.-madras-15246345/actors Puli Vesham https://ko.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/puli-vesham-7259315/actors Jeevana Jyothi https://ko.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/jeevana-jyothi-18126259/actors En Thangachi Padichava https://ko.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/en-thangachi-padichava-16248239/actors Seenu https://ko.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/seenu-7445924/actors Ponnu Veetukkaran https://ko.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/ponnu-veetukkaran-7227926/actors Sadhu https://ko.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/sadhu-7397863/actors Vanna Thamizh Pattu https://ko.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/vanna-thamizh-pattu-12988732/actors Asathal https://ko.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/asathal-4803654/actors Kadhal Kisu Kisu https://ko.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/kadhal-kisu-kisu-16852113/actors Vaimaye Vellum https://ko.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/vaimaye-vellum-17075827/actors Adhikari https://ko.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/adhikari-12913438/actors Senthamizh -

Shamanism in Ted Hughes's Poetry

LANGUAGE IN INDIA Strength for Today and Bright Hope for Tomorrow Volume 19:1 January 2019 ISSN 1930-2940 Managing Editor: M. S. Thirumalai, Ph.D. Editors: B. Mallikarjun, Ph.D. Sam Mohanlal, Ph.D. B. A. Sharada, Ph.D. A. R. Fatihi, Ph.D. Lakhan Gusain, Ph.D. Jennifer Marie Bayer, Ph.D. G. Baskaran, Ph.D. L. Ramamoorthy, Ph.D. C. Subburaman, Ph.D. (Economics) N. Nadaraja Pillai, Ph.D. Renuga Devi, Ph.D. Soibam Rebika Devi, M.Sc., Ph.D. Dr. S. Chelliah, Ph.D. Assistant Managing Editor: Swarna Thirumalai, M.A. Language in India www.languageinindia.com is included in the UGC Approved List of Journals. Serial Number 49042. Materials published in Language in India www.languageinindia.com are indexed in EBSCOHost database, MLA International Bibliography and the Directory of Periodicals, ProQuest (Linguistics and Language Behavior Abstracts) and Gale Research. The journal is listed in the Directory of Open Access Journals. It is included in the Cabell’s Directory, a leading directory in the USA. Articles published in Language in India are peer-reviewed by one or more members of the Board of Editors or an outside scholar who is a specialist in the related field. Since the dissertations are already reviewed by the University-appointed examiners, dissertations accepted for publication in Language in India are not reviewed again. This is our 19th year of publication. All back issues of the journal are accessible through this link: http://languageinindia.com/backissues/2001.html Language in India www.languageinindia.com ISSN 1930-2940 19:1 January 2019 List of Contents i Contents • Periyar University Department of English, Salem, Tamilnadu, India Papers presented in the National Seminar Food is not just a Curry: Raison de'tre of Food in Literature - FDLT 2019 .. -

Code Date Description Channel TV001 30-07-2017 & JARA HATKE STAR Pravah TV002 07-05-2015 10 ML LOVE STAR Gold HD TV003 05-02

Code Date Description Channel TV001 30-07-2017 & JARA HATKE STAR Pravah TV002 07-05-2015 10 ML LOVE STAR Gold HD TV003 05-02-2018 108 TEERTH YATRA Sony Wah TV004 07-05-2017 1234 Zee Talkies HD TV005 18-06-2017 13 NO TARACHAND LANE Zee Bangla HD TV006 27-09-2015 13 NUMBER TARACHAND LANE Zee Bangla Cinema TV007 25-08-2016 2012 RETURNS Zee Action TV008 02-07-2015 22 SE SHRAVAN Jalsha Movies TV009 04-04-2017 22 SE SRABON Jalsha Movies HD TV010 24-09-2016 27 DOWN Zee Classic TV011 26-12-2018 27 MAVALLI CIRCLE Star Suvarna Plus TV012 28-08-2016 3 AM THE HOUR OF THE DEAD Zee Cinema HD TV013 04-01-2016 3 BAYAKA FAJITI AIKA Zee Talkies TV014 22-06-2017 3 BAYAKA FAJITI AIYKA Zee Talkies TV015 21-02-2016 3 GUTTU ONDHU SULLU ONDHU Star Suvarna TV016 12-05-2017 3 GUTTU ONDU SULLU ONDU NIJA Star Suvarna Plus TV017 26-08-2017 31ST OCTOBER STAR Gold Select HD TV018 25-07-2015 3G Sony MIX TV019 01-04-2016 3NE CLASS MANJA B COM BHAGYA Star Suvarna TV020 03-12-2015 4 STUDENTS STAR Vijay TV021 04-08-2018 400 Star Suvarna Plus TV022 05-11-2015 5 IDIOTS Star Suvarna Plus TV023 27-02-2017 50 LAKH Sony Wah TV024 13-03-2017 6 CANDLES Zee Tamil TV025 02-01-2016 6 MELUGUVATHIGAL Zee Tamil TV026 05-12-2016 6 TA NAGAD Jalsha Movies TV027 10-01-2016 6-5=2 Star Suvarna TV028 27-08-2015 7 O CLOCK Zee Kannada TV029 02-03-2016 7 SAAL BAAD Sony Pal TV030 01-04-2017 73 SHAANTHI NIVAASA Zee Kannada TV031 04-01-2016 73 SHANTI NIVASA Zee Kannada TV032 09-06-2018 8 THOTAKKAL STAR Gold HD TV033 28-01-2016 9 MAHINE 9 DIWAS Zee Talkies TV034 10-02-2018 A Zee Kannada TV035 20-08-2017 -

Signatory ID

Signatory ID Name CIN Company Name 02050005 NARAYANA PARASU RAMAN U74140DL2008PTC176162 AAGS-PRADGA BIOTECH PRIVATE 02050011 DHIRUKUMAR PATEL U32109GJ2006PTC048621 TRUE SOLUSALES PRIVATE LIMITED 02050012 BHANDARI SHANTICHAND U51909MH2004PTC144101 BESTLINE MERCANTILE COMPANY 02050012 BHANDARI SHANTICHAND U45200MH2008PTC179711 WOODSIDE CONSTURCTIONS 02050023 BUCH ROHITKUMAR UTTAMLAL U51395GJ1999PLC036886 EFFLUENT CHANNEL PROJECT 02050028 RASTE SHANTANU SHARAD U24230MH2008PTC180694 PANCHAMVED PHARMA LAB 02050036 JOTHIMANI SUNDARAM U51909TZ2005PTC012404 FLUX EXPORTS (INDIA) PRIVATE 02050045 JAIN PRADEEP U67120MP2008PTC021247 MAGI FINSTOCK PRIVATE LIMITED 02050047 BHALODE RAJENDRA VASANT U85100MH2007PTC169519 KAMAL HEALTH CARE SERVICES 02050047 BHALODE RAJENDRA VASANT U01407MH2008PTC187593 KAMAL KRUSHI AGRO PRIVATE 02050049 PATEL RASIKBHAI RUCHIT U15209GJ2008PTC053135 KRUSHNA CREAM PROCESS 02050051 DEEPAK JAIN U45400DL2008PTC183140 SHRI PARSV PADMAVATI 02050051 DEEPAK JAIN U45400DL2008PTC183138 MANGLIK INFRASTRUCTURES 02050062 GARG KUMAR SANDEEP U70109PB2008PTC031772 SHIV SHANKAR INFRATECH 02050066 BHANDARI HEMANT U67120MP2008PTC021247 MAGI FINSTOCK PRIVATE LIMITED 02050067 ANBARASU SENNIAPPAN U74140TZ2005PTC012225 ACTIVE MANAGEMENT SOLUTIONS 02050075 PALKAR SONIA VIVEK U24110MH1972PTC016169 NIVEDITA CHEMICALS PRIVATE 02050075 PALKAR SONIA VIVEK U73100MH1979PTC021320 ANEK PRAYOG PRIVATE LIMITED 02050079 DHARMENDER YADAV U70101CH1993PLC013932 CONSOLIDATED DEALERS LIMITED 02050081 BHALODE RAJENDRA SAROJ U85100MH2007PTC169519 KAMAL HEALTH CARE -

Language Wise List of the Feature Films Indian/Foreign (Digital & Video)

Language wise List of the feature films Indian/Foreign (Digital & Video) Certified during period (01/01/2019 - 01/12/2019) Certified Type Of Film Certificate Sr. No Title Language Certificate No. Certificate Date Duration/ (Video/Digital/C Producer Name Production House Type Length elluloid) ARABIC ARABIC WITH ENGLISH 1 YOMEDDINE DFL/1/16/2019-MUM 26 March 2019 99.2 Digital WILD BUNCH - U SUBTITLES CAPHARNAUM ( Arabic With English Capharnaum Film 2 DFL/3/25/2019-MUM 02 May 2019 128.08 Digital - A CHILDREN OF CHAOS) Subtitles Ltd BVI CAPHARNAUM Arabic with English Capharnaum Film 3 VFL/2/448/2019-MUM 13 August 2019 127.54 Video - UA (CHILDREN OF CHAOS) Subtitles Ltd BVI ASSAMESE DREAM 1 KOKAIDEU BINDAAS Assamese DIL/1/1/2019-GUW 14 February 2019 120.4 Digital Rahul Modi U PRODUCTION Ajay Vishnu Children's Film 2 GATTU Assamese DIL/1/59/2019-MUM 22 March 2019 74.41 Digital U Chavan Society, India ASSAMESE WITH Anupam Kaushik Bhaworiya - The T- 3 BORNODI BHOTIAI DIL/1/5/2019-GUW 18 April 2019 120 Digital U ENGLISH SUBTITLES Borah Posaitives ASSAMESE WITH Kunjalata Gogoi 4 JANAKNANDINI DIL/1/8/2019-GUW 25 June 2019 166.23 Digital NIZI PRODUCTION U ENGLISH SUBTITLES Das SKYPLEX MOTION Nazim Uddin 5 ASTITTWA Assamese DIL/1/9/2019-GUW 04 July 2019 145.03 Digital PICTURES U Ahmed INTERNATIONAL FIREFLIES... JONAKI ASSAMESE WITH 6 DIL/3/2/2019-GUW 04 July 2019 93.06 Digital Milin Dutta vortex films A PORUA ENGLISH SUBTITLES ASSAMESE WITH 7 AAMIS DIL/2/4/2019-GUW 10 July 2019 109.07 Digital Poonam Deol Signum Productions UA ENGLISH SUBTITLES ASSAMESE WITH 8 JI GOLPOR SES NAI DIL/3/3/2019-GUW 26 July 2019 94.55 Digital Krishna Kalita M/S. -

List of Selected Candidates and Their Research Papers for the Year 2016-2017

List of Selected Candidates and their Research Papers for the Year 2016-2017 Junior Fellowship Research Papers S. Name &Address File No. Field/ Project Title No. Sub Field 1 Ms. Rupali Jain CCRT/JF- Classical Music Contribution Of Female Artist In 30- Sahyog Vihar E-8 Extension Near 3/001 /2018 Hindustani Vocal The Field Of Dhrupad Music Shahpura Thana Gulmohar Bhopal, (Musical Analysis And Bhopal, Madhya Pradesh- 462039 Transcription) Mobile No. 9300690926, Email- [email protected] 2 Shri Pradeep Kumar Chopra CCRT/JF- Classical Music Dhrupad Gaan Shaily Ko Vill- Deena P.O -Halduchour Ditt- 3/002 /2018 Hindustani Vocal Sanrakshit Karne Wale Nainital Uttrakhand India 263139 Rachnakaro ,Kalakaro Va Mobile No. – 9410581515 Ashradatao Ka Yogdan Email- [email protected] (Madhyakaal Se Adhunikaal Tak) 3 Shri Dhriti Gobinda Dutta CCRT/JF- Classical Music "SONOROUS SIBLINGS" -A C/O: C Barman, H.No: 3, Namghar Gali, 3/003 /2018 Hindustani Comparative Study Between Lutuma, Battalion Gate, Guwahati, Instrumental Sattriya Khol & Tabla Kamrup Metro, Assam- 781018 Mobile- 9678351108 Email- [email protected] 4 Shri Alok Mishra CCRT/JF- Classical Music Uttar Bharat Ki Sangritik Lok 319N/2 Harshwardhan Nagar Meerapur 3/004 /2018 Hindustani Kalaon Me Prayukt Lok Awnadh Allahabad, Uttar Pradesh- 211003 Instrumental Vadyo Ewam Vadko Ka Mobile No-.9389976650 Abhilekhikaran [email protected] 5 Ms. Kanchana S Shriranjani CCRT/JF- Classical Music The Influence Of Karnataka Music 1303, Navada, 24TH Cross, 28TH Main, 3/005 /2018 Carnatic Vocal On Yakshagana And Writing The Banashankari Ii Stage, Bangalore, Notation To Its Musical And Form Karnataka- 560070 Content (Literature) Mobile No- 9448100509 [email protected] 6 Ms. -

Mbbs/Bds Provisional Meritlist 2009/2010

MBBS/BDS PROVISIONAL MERITLIST 2009/2010 RANK ARNO Name Community Total Mark Com rank Eligibility 1 8411 KARTHIKA SANKAR BC 200.00 1 2 4826 BALAJIPRATHEP S BC 200.00 2 3 808 KARTHIKEYAN M A BC 200.00 3 4 9350 DEVASENA N BC 200.00 4 5 4119 VIGNESH S BC 200.00 5 6 6210 KARTHIKEYAN T BC 200.00 6 7 3572 PALANISAMY V MBC/DC 200.00 1 8 4985 VARSHINI RAMESH BC 200.00 7 9 6325 MONISHA PRIYADARSHINI K BC 199.75 8 10 4693 AARTHY G BC 199.75 9 11 2555 PRAVEEN A BC 199.75 10 12 2078 SATHYA SEELAN S BC 199.75 11 13 10010 NISHA V OC 199.75 14 5564 SANTHOSH KUMAR S BC 199.75 12 15 7133 NARMADHAM K B BC 199.75 13 16 3944 MUTHULAKSHMI S BC 199.75 14 17 774 ANISH H DEVA OC 199.75 18 5421 NIRMAL NITHIN A M BC 199.75 15 19 6492 CHINNA KUMARAVEL T BC 199.75 16 20 1202 RAMYA V BC 199.75 17 21 392 CHARANYA LAKSHMI B OC 199.75 22 5088 GRIDHARAN S BC 199.75 18 23 305 ROHINI R BC 199.75 19 24 6359 RAMESH B BC 199.75 20 25 5789 KANMANI M BC 199.75 21 26 5466 MONISHA T S BC 199.75 22 27 1061 KOPIKA S BC 199.75 23 28 4578 AISHWARIYA R BC 199.75 24 29 3997 PRADEEBAA T BC 199.75 25 30 3709 EASWAR E BC 199.75 26 31 10008 RAJA RATHINAM R BC 199.75 27 32 7677 THENDRAL N MBC/DC 199.75 2 33 593 CHARUMATHY A MBC/DC 199.75 3 34 5347 GNANASURIYAN R SC 199.75 1 35 916 DIVYA S MBC/DC 199.50 4 1 MBBS/BDS PROVISIONAL MERITLIST 2009/2010 RANK ARNO Name Community Total Mark Com rank Eligibility 36 7299 DHEAPAK V BC 199.50 28 37 1555 PRIYADARSHINI M BC 199.50 29 38 2272 ABBINAYA E BC 199.50 30 39 101 DAVASUMANI D BC 199.50 31 40 9289 JAZIMA SULAIHA S BCM 199.50 1 41 8856 APARNA DEVI -

Hindi & Tamil Learning Book हÛद और त मल सीखने क पुèतक

Hindi & Tamil Learning Book हद/ और तGमल सीखने क3 पु तक ஹிதி மN தமி! பய*P Eதக First Edition - January, 2014 Price: 100 AED (UAE Dirham) थम सं करण – जनवर/ २०१४ मयू : १०० ए इ Kड अGभ वीकृ Cत “ कोई भी अके ला नह/ं चलता, तो जैसे आप िजदगीं के सफर मQ आगे चलत े हS, आपको उन सबका शIHयाु करना है, जो आपके साथ जुड़,े जो आपके साथ चले और िजहUने सारे रा त े बराबर आपक3 मदद क3 ” अपनी खुद क3 कोGशशU के बावजूद, Iकसी भी प@रयोजना क3 सफलता दसरUू के \ोसाहन और मागदश% न% पर काफ़3 हद तक Cनभर% करती है | इस अवसर को लेत े हुए म,S उन लोगU का हाAद%क धयवाद अGभय2त करता हूँ, िजहUने इस प ु तक के समापन को सभवं Iकया है : सौरभ सद,ू गीता सद,ू सात ु दास, जीबन पॉल, सिमताु पॉल(जैमी), मीता पॉल, Aहरेन देब, Aदलशा Aदल/प, हसना बीजू, मीता दे, रजाथी बालाकु मार, अनपमु पॉल, Bबनॉय चौधुर/, ह@र पद रॉय, राजीब पॉल राके श और \ीतम पॉल | ताGमल भाग मQ एकमाW योगदान के Gलए ीमती रजाथी बालाकु मार, राधा \काश को Jवशषे धयवाद | खास तौर पर परमवरे का, मेरे प@रवार और दो तU का िजहUने इस काय % मQ, सब चीज़U को सभवं कर Aदखाया है | “You have to grow from the inside out. -

July 2020 Session Overall Merit List - Md/Ms Courses Rank Slno Roll No

JIPMER, PUDUCHERRY MD/MS ENTANCE EXAMINATION - JULY 2020 SESSION OVERALL MERIT LIST - MD/MS COURSES RANK SLNO ROLL NO. NAME OF THE CANDIDATE TOTAL MARKS DOB (dd/mm/yyyy) Percentile UR OBC SC ST EWS INST OPH Sponsored Foreign Eligibility 1 2007120166 DURGIA PARTH THAKUR 741 29/05/1996 99.9898837 1 Yes 2 2007114055 VINEETHA KANNEGANTI 718 19/01/1997 99.9797673 2 Yes 3 2007123321 VINITH KUMAR P R 697 22/09/1996 99.9696510 3 Yes 4 2007122664 INAMUL HASAN S 695 20/11/1996 99.9595346 4 1 Yes 5 2007110470 SELVAGANESAN M 689 18/03/1996 99.9494183 5 1 Yes 6 2007116464 SUBHAJIT DAS 680 22/07/1995 99.9393020 6 Yes 7 2007111110 ADITYA S NARAYAN 677 03/06/1996 99.9291856 7 Yes 8 2007123661 AKSHAYA J 675 12/09/1996 99.9190693 8 Yes 9 2007111683 SHAURYA SHARMA 666 08/09/1996 99.9089530 9 2 Yes 10 2007125025 SUVRANKAR DATTA 665 30/09/1996 99.8988366 10 3 Yes 11 2007116114 DIBYENDU SEKHAR DAS 664 16/01/1996 99.8887203 11 4 Yes 12 2007112411 ANAND V 662 13/07/1996 99.8786039 12 Yes 13 2007119543 SHUBHAM GOYAL 661 04/08/1997 99.8583713 13 Yes 14 2007113326 BIKASH SOURAV 661 18/06/1993 99.8583713 14 2 Yes 15 2007111699 BHUMIKA 659 05/11/1994 99.8482549 15 Yes 16 2007115625 MUPPANA VEERABHADRA VENKATA SAI SRIKANTH 656 04/05/1997 99.8381386 16 3 Yes 17 2007115294 ANAGHA PUNTAMBEKAR 654 13/07/1996 99.8280223 17 5 Yes 18 2007125774 MUDDANA POOJA SAI 651 02/01/1997 99.8179059 18 6 Yes 19 2007116210 SANIA RAHMAN 649 24/04/1994 99.8077896 19 7 Yes 20 2007115434 JAGPRIT SINGH 648 15/03/1996 99.7774406 20 Yes 21 2007110681 AISHWARYA R 648 16/06/1994 99.7774406 21 -

India Foundation for the Arts Annual Report 2015-16

India Foundation for the Arts Annual Report 2015-16 ‘ ‘ “IFA’s support went beyond the financial, and assumed various forms: by putting me in touch with other artists whose inputs were invaluable to my work, inviting the show to cities/spaces where we would normally never ABOUT IFA have performed, inviting eminent critics/audiences to the shows, and panel India Foundation for the Arts (IFA) is one of the country’s leading discussions that fostered dialogue based on my work. I am super glad to independent arts funders, championing the cause of arts philan- have been a grantee!” thropy and advocating the importance of the arts in public life. IFA began supporting the arts in 1995 and has made over 440 grants Sharanya Ramprakash, Grantee, Arts Practice Programme disbursing Rs 22 crore since. This year is special to us as we rejoice in completing 20 years of celebrating the arts. Our support has gone out to independent research and teaching institutions, cultural and development organisations, scholars and artists to facilitate critical research, cutting edge practice and edu- cation in the arts. We also act as a source of information and expertise to those in the arts community and beyond. MISSION IFA enriches the practice and knowledge of, widens public access to, and strengthens capacities and infrastructure in the arts in India, by supporting critical projects and creating public platforms. VISION To ensure that the arts, in all their diversity, are nurtured and val- ued because they enrich individual and community life and are critical to envisioning the future of our society.