The Link Between Prostitution and Human Trafficking

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gang Project Brochure Pg 1 020712

Salt Lake Area Gang Project A Multi-Jurisdictional Gang Intelligence, Suppression, & Diversion Unit Publications: The Project has several brochures available free of charge. These publications Participating Agencies: cover a variety of topics such as graffiti, gang State Agencies: colors, club drugs, and advice for parents. Local Agencies: Utah Dept. of Human Services-- Current gang-related crime statistics and Cottonwood Heights PD Div. of Juvenile Justice Services historical trends in gang violence are also Draper City PD Utah Dept. of Corrections-- available. Granite School District PD Law Enforcement Bureau METRO Midvale City PD Utah Dept. of Public Safety-- GANG State Bureau of Investigation Annual Gang Conference: The Project Murray City PD UNIT Salt Lake County SO provides an annual conference open to service Salt Lake County DA Federal Agencies: providers, law enforcement personnel, and the SHOCAP Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, community. This two-day event, held in the South Salt Lake City PD Firearms, and Explosives spring, covers a variety of topics from Street Taylorsville PD United States Attorney’s Office Survival to Gang Prevention Programs for Unified PD United States Marshals Service Schools. Goals and Objectives commands a squad of detectives. The The Salt Lake Area Gang Project was detectives duties include: established to identify, control, and prevent Suppression and street enforcement criminal gang activity in the jurisdictions Follow-up work on gang-related cases covered by the Project and to provide Collecting intelligence through contacts intelligence data and investigative assistance to with gang members law enforcement agencies. The Project also Assisting local agencies with on-going provides youth with information about viable investigations alternatives to gang membership and educates Answering law-enforcement inquiries In an emergency, please dial 911. -

Private Conflict, Local Organizations, and Mobilizing Ethnic Violence In

Private Conflict, Local Organizations, and Mobilizing Ethnic Violence in Southern California Bradley E. Holland∗ Abstract Prominent research highlights links between group-level conflicts and low-intensity (i.e. non-militarized) ethnic violence. However, the processes driving this relationship are often less clear. Why do certain actors attempt to mobilize ethnic violence? How are those actors able to mobilize participation in ethnic violence? I argue that addressing these questions requires scholars to focus not only on group-level conflicts and tensions, but also private conflicts and local violent organizations. Private conflicts give certain members of ethnic groups incentives to mobilize violence against certain out-group adversaries. Institutions within local violent organizations allow them to mobilize participation in such violence. Promoting these selective forms of violence against out- group adversaries mobilizes indiscriminate forms of ethnic violence due to identification problems, efforts to deny adversaries access to resources, and spirals of retribution. I develop these arguments by tracing ethnic violence between blacks and Latinos in Southern California. In efforts to gain leverage in private conflicts, a group of Latino prisoners mobilized members of local street gangs to participate in selective violence against African American adversaries. In doing so, even indiscriminate forms of ethnic violence have become entangled in the private conflicts of members of local violent organizations. ∗Assistant Professor, Department of Political Science, The Ohio State University, [email protected]. Thanks to Sarah Brooks, Jorge Dominguez, Jennifer Hochschild, Didi Kuo, Steven Levitsky, Chika Ogawa, Meg Rithmire, Annie Temple, and Bernardo Zacka for comments on earlier drafts. 1 Introduction On an evening in August 1992, the homes of two African American families in the Ramona Gardens housing projects, just east of downtown Los Angeles, were firebombed. -

2016 Annual Report United States Department of Justice United States Attorney’S Office Central District of California

2016 Annual Report United States Department of Justice United States Attorney’s Office Central District of California TABLE OF CONTENTS Letter from U.S. Attorney Eileen M. Decker ____________________________________________________________________ 3 Introduction ______________________________________________________________________________________________________ 5 Overview of Cases ________________________________________________________________________________________________ 6 Assaults on Federal Officers ___________________________________________________________________________________ 6 Appeals __________________________________________________________________________________________________________ 7 Bank and Mortgage Fraud ____________________________________________________________________________________ 10 Civil Recovery _________________________________________________________________________________________________ 15 Civil Rights _____________________________________________________________________________________________________ 16 Community Safety _____________________________________________________________________________________________ 19 Credit Fraud ___________________________________________________________________________________________________ 21 Crimes and Fraud against the Government _________________________________________________________________ 22 Cyber Crimes __________________________________________________________________________________________________ 26 Defending the United States __________________________________________________________________________________ -

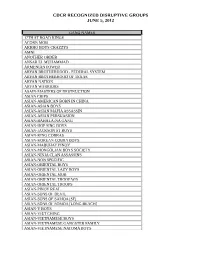

Cdcr Recognized Disruptive Groups June 5, 2012

CDCR RECOGNIZED DISRUPTIVE GROUPS JUNE 5, 2012 GANG NAMES 17TH ST ROAD KINGS ACORN MOB AKRHO BOYS CRAZZYS AMNI ANOTHER ORDER ANSAR EL MUHAMMAD ARMENIAN POWER ARYAN BROTHERHOOD - FEDERAL SYSTEM ARYAN BROTHERHOOD OF TEXAS ARYAN NATION ARYAN WARRIORS ASAIN-MASTERS OF DESTRUCTION ASIAN CRIPS ASIAN-AMERICAN BORN IN CHINA ASIAN-ASIAN BOYS ASIAN-ASIAN MAFIA ASSASSIN ASIAN-ASIAN PERSUASION ASIAN-BAHALA-NA GANG ASIAN-HOP SING BOYS ASIAN-JACKSON ST BOYS ASIAN-KING COBRAS ASIAN-KOREAN COBRA BOYS ASIAN-MABUHAY PINOY ASIAN-MONGOLIAN BOYS SOCIETY ASIAN-NINJA CLAN ASSASSINS ASIAN-NON SPECIFIC ASIAN-ORIENTAL BOYS ASIAN-ORIENTAL LAZY BOYS ASIAN-ORIENTAL MOB ASIAN-ORIENTAL TROOP W/S ASIAN-ORIENTAL TROOPS ASIAN-PINOY REAL ASIAN-SONS OF DEVIL ASIAN-SONS OF SAMOA [SF] ASIAN-SONS OF SOMOA [LONG BEACH] ASIAN-V BOYS ASIAN-VIET CHING ASIAN-VIETNAMESE BOYS ASIAN-VIETNAMESE GANGSTER FAMILY ASIAN-VIETNAMESE NATOMA BOYS CDCR RECOGNIZED DISRUPTIVE GROUPS JUNE 5, 2012 ASIAN-WAH CHING ASIAN-WO HOP TO ATWOOD BABY BLUE WRECKING CREW BARBARIAN BROTHERHOOD BARHOPPERS M.C.C. BELL GARDENS WHITE BOYS BLACK DIAMONDS BLACK GANGSTER DISCIPLE BLACK GANGSTER DISCIPLES NATION BLACK GANGSTERS BLACK INLAND EMPIRE MOB BLACK MENACE MAFIA BLACK P STONE RANGER BLACK PANTHERS BLACK-NON SPECIFIC BLOOD-21 MAIN BLOOD-916 BLOOD-ATHENS PARK BOYS BLOOD-B DOWN BOYS BLOOD-BISHOP 9/2 BLOOD-BISHOPS BLOOD-BLACK P-STONE BLOOD-BLOOD STONE VILLAIN BLOOD-BOULEVARD BOYS BLOOD-BOUNTY HUNTER BLOOD-BOUNTY HUNTER [LOT BOYS] BLOOD-BOUNTY HUNTER-BELHAVEN BLOOD-BOUNTY HUNTER-INCKERSON GARDENS BLOOD-BOUNTY HUNTER-NICKERSON -

Mexican Mafia Timeline

MEXICAN MAFIA TIMELINE April 24, 1923 Henry "Hank" Leyva born in Tuscon, Arizona. April 10, 1929 Joe "Pegleg" Morgan born. 1935 1st generation "Originals" of Hoyo Maravilla gang forms. 1939 2nd generation "Cherries" of Hoyo Maravilla gang forms. December 1941 Henry "Hank" Leyva, Joe Valenzuela and Jack Melendez all members from 38th street gang in Long Beach arrested on suspicion of armed robbery. Charges dropped against Joe Valenzuela and Jack Melendez but Leyva is rebooked on a charge of assault with a deadly weapon. Leyva pled guilty and received a 3 month county jail term. August 2, 1942 Gang fight involving 38th street gang from Long Beach and a Downey gang results in the death of Jose Diaz. January 13, 1943 11 members of the 38th street gang are sentenced to prison for the murder of Jose Diaz. June 3, 1943 The Zoot suites erupt in Los Angeles. Many blame the racial tension in the city as a result of the treatment hispanics were subjected to while they searched for the killers of Jose Diaz. October 4, 1943 District Court of Appeals dismisses the case against the members of the 38th st., and orders them freed from custody. 1946 Joe Morgan [Maravilla gang] beats the husband of his 32 year old girlfriend to death and buries the body in a shallow grave. While awaiting trial he escapes using the identification papers of a fellow inmate awaiting transfer to a forestry camp. He is recaptured and sentenced to 9 years at San Quentin.. 1954 South Ontario Black Angels gang is formed. -

Gun Violence in the LAPD 77Th Street Area: Research Results and Policy Options

Gun Violence in the LAPD 77th Street Area Research Results and Policy Options GEORGE TITA, SCOTT HIROMOTO, JEREMY WILSON, JOHN CHRISTIAN, CLIFFORD GRAMMICH WR-128-OJP January 2004 Prepared for Office of Justice Programs Gun Violence in the Los Angeles Police Department (LAPD) 77th Street Area: Background Information and Policy Options Introduction This document is intended to aid the U.S. Attorney’s Office in designing and implementing a Project Safe Neighborhoods gun-violence reduction strategy in the 77th Street Area of the Los Angeles Police Department. (A future analysis, pending approved access to and analysis of homicide records, will focus on the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Century Station and its nearby areas.) We consider three topics: 1. Analysis of data on the 322 homicides, most of which were gang related, in the area from January 1998 through March 2003 2. Insights gathered from interviews with local experts, including police officers, probation officers, and community representatives, including their assessment of individual gangs in the area 3. A review of three potential interventions implemented elsewhere and the pros and cons of applying them to the 77th Street area Analysis of Homicide Data We chose to analyze homicide data to gauge violence in the area because no other type of crime gets more time and attention than homicide, and because homicide has been shown to be a good proxy for other types of violence, especially gun assaults. The difference between a homicide and an attempted homicide or an aggravated assault, for example, rarely depends on the intent of the offender but rather on the location of the wound and the speed of medical attention. -

Gangs-Overview-LES-FOUO.Pdf

2 Updated 10/2010 850,000 - Gang members in 31,000 gangs in the United States 300,000 - Gang members in over 2,000 gangs in California 150,000 - Gang members in over 1000 gangs in Los Angeles County 20,000 - Gang members in Orange County 10,000 - Gang members in San Diego County 1,000 - Gang members in Imperial County • Estimated Strengths Circ: 2008 • 97,000 LA County Gang Members • 6,700 Female Gang Members (6.7%) • 28,400 Black Gang Members • 58,800 Hispanic Gang Members • 3,500 Asian Gang Members • 311 Black Gangs (83 Blood) • 573 Hispanic Gangs • 104 Asian Gangs • 28 White Gangs • 18,000 LA Morgue Bodies Processed • 326 Gang Fatalities in 2009 • These numbers are based on actual identified members, not estimates (2009) A group of three or more persons who are united by a common ideology that revoles around criminal activity • Gangs are not part of one’s ethnic culture • Gangs are part of a criminal culture • The gang comes before religion, family, marriage, community, friendship and the law. “Barney” Mayberry Crips - Criminal Gangs: Members conspire or commit criminal acts for the benefit of the gang - Traditional Gangs: Common name or symbol and claim territory - Non-Traditional Gangs: Do not claim territory, but may have a location that members frequent • Taggers/Bombers • Party Crews • Rappers Young tagger in training • Gothics • Punks • Stoners • Car Clubs • SHARP Skin Heads • Occult Gangs Identity or Recognition - Allows a gang member to achieve a level or status he feels impossible outside the gang culture. They visualize themselves as warriors protecting their neighborhood. -

Cerritos College Now Offers 2 Years of Free Tuition

Friday, Feb. 15, 2019 Vol. 13 No. 2 14783 Carmenita Road, Norwalk, CA 90650 Jason Barquero, public address Norwalk announcer for the South Bay Lakers, delivered the keynote address at the restaurant 49th annual Mayor’s Prayer Breakfast in Norwalk on Wednesday. grades Barquero’s roots in public broadcasting El Marinero date back to the late 90s, when he was 11025 E Alondra Blvd. a student at Cerritos College and helped Date Inspected: 2/4/19 FridayWeekend58˚ launch the school’s first interet radio Grade: A station. at a Cerritos College Cafeteria Glance In addition to his work within the Lakers 11110 E Alondra Blvd. Saturday 6859˚⁰ organization, Barquero is also executive Date Inspected: 2/4/19 Friday director of career services at Otis College Grade: A of Art & Design. Huh Daegam Restaurant Sunday 57˚ ⁰ 16511 Pioneer Blvd. Ste. 104 Saturday 70 Date Inspected: 2/4/19 Grade: A Starbucks 14322 Pioneer Blvd. PhOtO COurteSy CIty Of NOrWALk Date Inspected: 2/1/19 Grade: A Kikka 11660 Firestone Blvd. Date Inspected: 1/31/19 Cerritos College now offers 2 years Grade: A Painting & Pancakes Northgate (Meat) Saturday - Norwalk Cultural Arts 11660 E Firestone Blvd. Center, 10 am Date Inspected: 1/31/19 of free tuition Make a brunch date with your favorite Grade: A little painter. Open to children ages 6 and up and any adult guardian. Cerritos Complete goes beyond “We believe that adding Northgate (Tortilleria) the programs across the state another year of free tuition is 11660 E Firestone Blvd. that offer one year of free going to give even more students Date Inspected: 1/31/19 college tuition. -

Download: Brill.Com/Brill-Typeface

Women and Knowledge in Early Christianity Supplements to Vigiliae Christianae texts and studies of early christian life and language Editors-in-Chief D.T. Runia G. Rouwhorst Editorial Board J. den Boeft B.D. Ehrman K. Greschat J. Lössl J. van Oort C. Scholten volume 144 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/vcs Women and Knowledge in Early Christianity Edited by Ulla Tervahauta Ivan Miroshnikov Outi Lehtipuu Ismo Dunderberg leiden | boston This title is published in Open Access with the support of the University of Helsinki Library. This is an open access title distributed under the terms of the CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 license, which permits any non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided no alterations are made and the original author(s) and source are credited. Further information and the complete license text can be found at https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ The terms of the CC license apply only to the original material. The use of material from other sources (indicated by a reference) such as diagrams, illustrations, photos and text samples may require further permission from the respective copyright holder. The Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available online at http://catalog.loc.gov Typeface for the Latin, Greek, and Cyrillic scripts: “Brill”. See and download: brill.com/brill-typeface. issn 0920-623x isbn 978-90-04-35543-9 (hardback) isbn 978-90-04-34493-8 (e-book) Copyright 2017 by the Authors. Published by Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, The Netherlands. -

LA Gang Injunction Complaint

1 EDMUND G. BROWN JR. CONFORMED COPY Attorney General of the State ofCali fornia OF ORIGINAL FILED 2 LOUIS VERDUGO, JR. Los Angeles Superior Court Senior Assistant Attorney General 3 ANGELA SIERRA JUN 12 2009 Supervising Deputy Attorney General 4 DAVlD 1 BASS John A. OlficerlDerk Deputy Attorney General By Z" , Deputy 5 ANTHONY V. SEFERlAN S LEY Deputy AttomeyGeneral (Stale Bar No. 142741) 6 BOO I Street, Suite 11 01, P.O. Box 944255 Sacramento, California 94244-2550 7 (916) 445-8227; Fax: (916) 327-2319 Email: [email protected] 8 9 ROCKARD J. DELGADILLO Los Angeles City Attorney (Bar No. 125465x) 10 JEFFREY B. ISAACS Chief Assistaot City Attorney (Bar No. 117104) 11 BRUCE RIORDAN Senior Assistaot City Attorney (Bar No. 127230) 12 ANNE C. TREMBLAY Assistant City Attorney (Bar No. 180956) 13 KEllY HUYNH Deputy City Attorney (Bar No. 175156) 14 200 N. Main Street, 9th Floor, Room #%6 Los Angeles, California 90012 15 (213) 978-4090; Fax (213) 978-8717 Email: [email protected] 16 Attorneys for Plaintiff, 17 People ofthe Stale of California I ir SUPERIOR COURT OF THE STATE OF CALIFORNIA 19 FOR THE COUNTY OFLOS ANGELES 20 PEOPLE OF STATE OF CALIFORNIA, nrn Case No.: .R C4 1 5 69 ex reL Edmund G. Brown Jr., as the (Unlimited civil ease,.. 4 21 Attorney General of the State of California, and ex reL Rockar-d J. DelgadIllo, as the COMPLAINT FOR INJUNCTIVE 22 City Attorney for the City of Los Angeles, RELIEF FOR VIOLATIONS OF nrn BANE CIVIL RIGHTS ACf AND 23 Plain!ilI, PUBLIC NUISANCE LAWS 24 vs. -

147227NCJRS.Pdf

If you have issues viewing or accessing this file contact us at NCJRS.gov. ., l' .;-.....- ~- ~ .-', ,-" -.- ... , _.-:"l.~"'-"if,-- • "",. ~--'-"'-~-'--- ..... .. - -r",' ",,~.-_ ""'. ~---.. ~-- .. ... ~t of" .~ de.: .~. ~;6 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Preface i Introduction 1 Alabama 3 Black Gangster Disciples 3 Arizona 4 Southside Posse 4 Arkansas 4 Niggers With An Attitude 4 Califomia 4 F-Tfoop 4 Lapers 5 Harpys 5 18th Street 7 Connecticut 7 Kensington Street International 7 Florida 8 International Posse 8 Zulu 8 308 Street Boys 8 Georgia 9 Major Problems 9 Phinokes 9 Illinois 9 Black Gangster DAsciples 9 EIRukns 10 Latin Kings 10 Vice Lords 10 Indiana 12 Disciples 12 Louisiana 12 Bally Boys 12 Massachusetts 12 X-Men 12 Michigan 13 Best Friends 13 Peoples Organization 13 Minnesota 14 Vice Lords 14 Missouri 15 Sydney Street Hustlers 15 New Mexico 15 Juaritos 15 North Carolina 15 Juice Crew 15 Ohio 16 Ready-Rock Boys 16 Pennsylvania 16 Junior Black Mafia 16 Texas 17 East Side Locos 17 Greenspoint Posse 17 Latin Kings 17 Virginia 18 Fila Mafia 18 Washington 18 Black Gangster Disciples 18 Wisconsin 19 Brothers of the Struggle 19 Bulletin 19 black Gangster Disciples 19 Peoples Organization 19 Conclusion 21 Index 23 -------- ------~----------~- PREFACE A major objective of the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms is to help decrease the violence associated with street gangs throughout the United States. The intention of this intelligence booklet is to provide information in support of that objective. It will be distributed throughout the law enforcement community. This publication is not all inclusive. It does, however, include the gangs that have been reported as the most criminally active. -

Running Towards Runaways

Young Visionaries Youth Leadership Academy Stones’ Theory On Gang Relationships, Memberships and Exit Strategies Questionnaire (Please Fill Out thank You) Name: 1. What is your favorite color, band, or even leisure activity? 2. Would you like to take a stroll or join a sport activity while on beach? 3. Do you like to dance? 4. Are you interested in traveling? 5. What would you prefer - flowers, candy or books? 1 Name That Gang Game Young Visionaries Youth Leadership Academy 18th Street Gang (18th St) 101 Crip Gang 40 Ounce Gang 104st. (Inglewood) 38St - South Los Angeles 21st Street 8th Street Acacia Block Compton Crips 29th Street Alley Tiny Criminals (ATC) – Southside Alley Tiny Criminals (ATCX3) - South Los Angeles 33rd Street Barrio Mojados (BMS 43) Anaheim Vatos Locos (AVLS 13) 38th Street Barrio Mojados (BMS 82) Anzac Grape Compton Crips 39th Street Big Hazard (BH) Assassins - a clique of the Avenues gang, 3rd Street Crips Highland Park Breed Street Atlantic Drive Compton Crips 41st Street Carnales 13 (CxL) Avenue 43rd - Highland Park. 42nd Street Lil Criminals (FSLC) Clanton 14 (ES C14) Azusa trese (13) 50th Street Cuatro Flats Baldwin Park Trese (BP 13) 55 Bunch Diamond Street(DST) Ballista St.(La Puente) A Line Crips East LA Dukes Bartlett Gang (S.G.V.) Aliso Village Brim East Side Locos Bassett Chicos All For Crime Evergreen Bassett Grande Angelo Mafia Crips Fickette Bassett Nite Owls Avalon 40′s Crips Florencia (SS F) Big Bolen Avalon Gangster Crips, 53 Ghetto Boys (GBZ) Big Hazard, based in East Los Angeles Avalon Ganster