Operation Sudden Impact: the Effective Use of Federal and State Resources to Combat Gang Violence Reema M

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gang Project Brochure Pg 1 020712

Salt Lake Area Gang Project A Multi-Jurisdictional Gang Intelligence, Suppression, & Diversion Unit Publications: The Project has several brochures available free of charge. These publications Participating Agencies: cover a variety of topics such as graffiti, gang State Agencies: colors, club drugs, and advice for parents. Local Agencies: Utah Dept. of Human Services-- Current gang-related crime statistics and Cottonwood Heights PD Div. of Juvenile Justice Services historical trends in gang violence are also Draper City PD Utah Dept. of Corrections-- available. Granite School District PD Law Enforcement Bureau METRO Midvale City PD Utah Dept. of Public Safety-- GANG State Bureau of Investigation Annual Gang Conference: The Project Murray City PD UNIT Salt Lake County SO provides an annual conference open to service Salt Lake County DA Federal Agencies: providers, law enforcement personnel, and the SHOCAP Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, community. This two-day event, held in the South Salt Lake City PD Firearms, and Explosives spring, covers a variety of topics from Street Taylorsville PD United States Attorney’s Office Survival to Gang Prevention Programs for Unified PD United States Marshals Service Schools. Goals and Objectives commands a squad of detectives. The The Salt Lake Area Gang Project was detectives duties include: established to identify, control, and prevent Suppression and street enforcement criminal gang activity in the jurisdictions Follow-up work on gang-related cases covered by the Project and to provide Collecting intelligence through contacts intelligence data and investigative assistance to with gang members law enforcement agencies. The Project also Assisting local agencies with on-going provides youth with information about viable investigations alternatives to gang membership and educates Answering law-enforcement inquiries In an emergency, please dial 911. -

A Constitutional Analysis of the Ogden Trece Gang Injunction Megan K

Utah OnLaw: The Utah Law Review Online Supplement Volume 2013 Article 22 2013 Removing the Presumption of Innocence: A Constitutional Analysis of the Ogden Trece Gang Injunction Megan K. Baker Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.law.utah.edu/onlaw Part of the Civil Rights and Discrimination Commons, Constitutional Law Commons, and the Criminal Law Commons Recommended Citation Baker, Megan K. (2013) "Removing the Presumption of Innocence: A Constitutional Analysis of the Ogden Trece Gang Injunction," Utah OnLaw: The Utah Law Review Online Supplement: Vol. 2013 , Article 22. Available at: https://dc.law.utah.edu/onlaw/vol2013/iss1/22 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Utah Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Utah OnLaw: The tU ah Law Review Online Supplement by an authorized editor of Utah Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. REMOVING THE PRESUMPTION OF INNOCENCE: A CONSTITUTIONAL ANALYSIS OF THE OGDEN TRECE GANG INJUNCTION Megan K. Baker* Abstract Gang activity poses a substantial problem in many communities. The city of Ogden, Utah, is home to many gangs, and law enforcement is constantly looking for a way to decrease gang violence. In an attempt to reduce gang violence in Ogden, Judge Ernie Jones issued the Ogden Trece gang injunction on September 27, 2010, in Weber County, Utah. The injunction, based on several similar injunctions in California, affects hundreds of alleged Ogden Trece gang members and spans an area including virtually the entire city of Ogden. The injunction prohibits those enjoined from engaging in various illegal activities as well as many otherwise legal activities. -

Private Conflict, Local Organizations, and Mobilizing Ethnic Violence In

Private Conflict, Local Organizations, and Mobilizing Ethnic Violence in Southern California Bradley E. Holland∗ Abstract Prominent research highlights links between group-level conflicts and low-intensity (i.e. non-militarized) ethnic violence. However, the processes driving this relationship are often less clear. Why do certain actors attempt to mobilize ethnic violence? How are those actors able to mobilize participation in ethnic violence? I argue that addressing these questions requires scholars to focus not only on group-level conflicts and tensions, but also private conflicts and local violent organizations. Private conflicts give certain members of ethnic groups incentives to mobilize violence against certain out-group adversaries. Institutions within local violent organizations allow them to mobilize participation in such violence. Promoting these selective forms of violence against out- group adversaries mobilizes indiscriminate forms of ethnic violence due to identification problems, efforts to deny adversaries access to resources, and spirals of retribution. I develop these arguments by tracing ethnic violence between blacks and Latinos in Southern California. In efforts to gain leverage in private conflicts, a group of Latino prisoners mobilized members of local street gangs to participate in selective violence against African American adversaries. In doing so, even indiscriminate forms of ethnic violence have become entangled in the private conflicts of members of local violent organizations. ∗Assistant Professor, Department of Political Science, The Ohio State University, [email protected]. Thanks to Sarah Brooks, Jorge Dominguez, Jennifer Hochschild, Didi Kuo, Steven Levitsky, Chika Ogawa, Meg Rithmire, Annie Temple, and Bernardo Zacka for comments on earlier drafts. 1 Introduction On an evening in August 1992, the homes of two African American families in the Ramona Gardens housing projects, just east of downtown Los Angeles, were firebombed. -

Mara Salvatrucha: the Most Dangerous Gang in America

Mara Salvatrucha: The Deadliest Street Gang in America Albert DeAmicis July 31, 2017 Independent Study LaRoche College Mara Salvatrucha: The Deadliest Street Gang in America Abstract The following paper will address the most violent gang in America: Mara Salvatrucha or MS-13. The paper will trace the gang’s inception and its development exponentially into this country. MS-13’s violence has increased ten-fold due to certain policies and laws during the Obama administration, as in areas such as Long Island, New York. Also Suffolk County which encompasses Brentwood and Central Islip and other areas in New York. Violence in these communities have really raised the awareness by the Trump administration who has declared war on MS-13. The Department of Justice under the Trump administration has lent their full support to Immigration Custom Enforcement (ICE) to deport these MS-13 gang members back to their home countries such as El Salvador who has been making contingency plans to accept this large influx of deportations of MS-13 from the United States. It has been determined by Garcia of Insight.com that MS-13 has entered into an alliance with the security threat group, the Mexican Mafia or La Eme, a notorious prison gang inside the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation. The Mexican Drug Trafficking Organization [Knights Templar] peddles their drugs throughout a large MS-13 national network across the country. This MS-13 street gang is also attempting to move away from a loosely run clique or clikas into a more structured organization. They are currently attempting to organize the hierarchy by combining both west and east coast MS-13 gangs. -

2016 Annual Report United States Department of Justice United States Attorney’S Office Central District of California

2016 Annual Report United States Department of Justice United States Attorney’s Office Central District of California TABLE OF CONTENTS Letter from U.S. Attorney Eileen M. Decker ____________________________________________________________________ 3 Introduction ______________________________________________________________________________________________________ 5 Overview of Cases ________________________________________________________________________________________________ 6 Assaults on Federal Officers ___________________________________________________________________________________ 6 Appeals __________________________________________________________________________________________________________ 7 Bank and Mortgage Fraud ____________________________________________________________________________________ 10 Civil Recovery _________________________________________________________________________________________________ 15 Civil Rights _____________________________________________________________________________________________________ 16 Community Safety _____________________________________________________________________________________________ 19 Credit Fraud ___________________________________________________________________________________________________ 21 Crimes and Fraud against the Government _________________________________________________________________ 22 Cyber Crimes __________________________________________________________________________________________________ 26 Defending the United States __________________________________________________________________________________ -

History of Gangs in the United States

1 ❖ History of Gangs in the United States Introduction A widely respected chronicler of British crime, Luke Pike (1873), reported the first active gangs in Western civilization. While Pike documented the existence of gangs of highway robbers in England during the 17th century, it does not appear that these gangs had the features of modern-day, serious street gangs. Later in the 1600s, London was “terrorized by a series of organized gangs calling themselves the Mims, Hectors, Bugles, Dead Boys [and they] fought pitched battles among themselves dressed with colored ribbons to distinguish the different factions” (Pearson, 1983, p. 188). According to Sante (1991), the history of street gangs in the United States began with their emer- gence on the East Coast around 1783, as the American Revolution ended. These gangs emerged in rapidly growing eastern U.S. cities, out of the conditions created in large part by multiple waves of large-scale immigration and urban overcrowding. This chapter examines the emergence of gang activity in four major U.S. regions, as classified by the U.S. Census Bureau: the Northeast, Midwest, West, and South. The purpose of this regional focus is to develop a better understanding of the origins of gang activity and to examine regional migration and cultural influences on gangs themselves. Unlike the South, in the Northeast, Midwest, and West regions, major phases characterize gang emergence. Table 1.1 displays these phases. 1 2 ❖ GANGS IN AMERICA’S COMMUNITIES Table 1.1 Key Timelines in U.S. Street Gang History Northeast Region (mainly New York City) First period: 1783–1850s · The first ganglike groups emerged immediately after the American Revolution ended, in 1783, among the White European immigrants (mainly English, Germans, and Irish). -

Susany. Soong Clerk, U.S. District Court Northern

FILED 1 STEPHANIE M. HINDS (CABN 154284) Acting United States Attorney 2 Apr 15 2021 3 SUSANY. SOONG 4 CLERK, U.S. DISTRICT COURT NORTHERN DISTRICT OF CALIFORNIA 5 SAN FRANCISCO 6 7 8 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT 9 NORTHERN DISTRICT OF CALIFORNIA 10 SAN FRANCISCO DIVISION 11 UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, ) CASE NO. 3:21-cr-00153 VC ) 12 Plaintiff, ) VIOLATIONS: ) 18 U.S.C. §§ 924(j)(1) and 2 – Use of a Firearm in 13 v. ) Furtherance of a Crime of Violence Resulting in ) Death; 14 JONATHAN ESCOBAR, ) 18 U.S.C. §§ 924(c)(1)(A) and 2 – Use/Carrying of a a/k/a “Wicked,” a/k/a “Rico,” and ) Firearm During and in Relation to a Crime of 15 JOSE AGUILAR, ) Violence; a/k/a “Slim” ) 18 U.S.C. § 924(d) and 28 U.S.C. § 2461(c) – 16 ) Forfeiture Allegation Defendants. ) 17 ) SAN FRANCISCO VENUE ) 18 ) UNDER SEAL ) 19 20 I N D I C T M E N T 21 The Grand Jury charges, with all dates being approximate and all date ranges being both 22 approximate and inclusive, and at all times relevant to this Indictment: 23 Introductory Allegations 24 1. The 19th Street Sureños gang was a predominantly Hispanic street gang that claimed the 25 area centered around 19th Street and Mission Street, in the Mission District of San Francisco, as its 26 territory or “turf.” The claimed territory included the area bounded by 19th Street to the South, 16th 27 Street to the North, Folsom Street to the East, and Dolores Street to the West. -

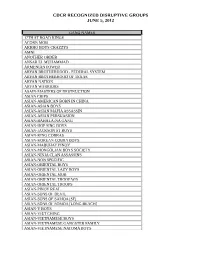

Cdcr Recognized Disruptive Groups June 5, 2012

CDCR RECOGNIZED DISRUPTIVE GROUPS JUNE 5, 2012 GANG NAMES 17TH ST ROAD KINGS ACORN MOB AKRHO BOYS CRAZZYS AMNI ANOTHER ORDER ANSAR EL MUHAMMAD ARMENIAN POWER ARYAN BROTHERHOOD - FEDERAL SYSTEM ARYAN BROTHERHOOD OF TEXAS ARYAN NATION ARYAN WARRIORS ASAIN-MASTERS OF DESTRUCTION ASIAN CRIPS ASIAN-AMERICAN BORN IN CHINA ASIAN-ASIAN BOYS ASIAN-ASIAN MAFIA ASSASSIN ASIAN-ASIAN PERSUASION ASIAN-BAHALA-NA GANG ASIAN-HOP SING BOYS ASIAN-JACKSON ST BOYS ASIAN-KING COBRAS ASIAN-KOREAN COBRA BOYS ASIAN-MABUHAY PINOY ASIAN-MONGOLIAN BOYS SOCIETY ASIAN-NINJA CLAN ASSASSINS ASIAN-NON SPECIFIC ASIAN-ORIENTAL BOYS ASIAN-ORIENTAL LAZY BOYS ASIAN-ORIENTAL MOB ASIAN-ORIENTAL TROOP W/S ASIAN-ORIENTAL TROOPS ASIAN-PINOY REAL ASIAN-SONS OF DEVIL ASIAN-SONS OF SAMOA [SF] ASIAN-SONS OF SOMOA [LONG BEACH] ASIAN-V BOYS ASIAN-VIET CHING ASIAN-VIETNAMESE BOYS ASIAN-VIETNAMESE GANGSTER FAMILY ASIAN-VIETNAMESE NATOMA BOYS CDCR RECOGNIZED DISRUPTIVE GROUPS JUNE 5, 2012 ASIAN-WAH CHING ASIAN-WO HOP TO ATWOOD BABY BLUE WRECKING CREW BARBARIAN BROTHERHOOD BARHOPPERS M.C.C. BELL GARDENS WHITE BOYS BLACK DIAMONDS BLACK GANGSTER DISCIPLE BLACK GANGSTER DISCIPLES NATION BLACK GANGSTERS BLACK INLAND EMPIRE MOB BLACK MENACE MAFIA BLACK P STONE RANGER BLACK PANTHERS BLACK-NON SPECIFIC BLOOD-21 MAIN BLOOD-916 BLOOD-ATHENS PARK BOYS BLOOD-B DOWN BOYS BLOOD-BISHOP 9/2 BLOOD-BISHOPS BLOOD-BLACK P-STONE BLOOD-BLOOD STONE VILLAIN BLOOD-BOULEVARD BOYS BLOOD-BOUNTY HUNTER BLOOD-BOUNTY HUNTER [LOT BOYS] BLOOD-BOUNTY HUNTER-BELHAVEN BLOOD-BOUNTY HUNTER-INCKERSON GARDENS BLOOD-BOUNTY HUNTER-NICKERSON -

HISTORY of STREET GANGS in the UNITED STATES By: James C

Bureau of Justice Assistance U.S. Department of Justice NATIO N AL GA ng CE N TER BULLETI N No. 4 May 2010 HISTORY OF STREET GANGS IN THE UNITED STATES By: James C. Howell and John P. Moore Introduction The first active gangs in Western civilization were reported characteristics of gangs in their respective regions. by Pike (1873, pp. 276–277), a widely respected chronicler Therefore, an understanding of regional influences of British crime. He documented the existence of gangs of should help illuminate key features of gangs that operate highway robbers in England during the 17th century, and in these particular areas of the United States. he speculates that similar gangs might well have existed in our mother country much earlier, perhaps as early as Gang emergence in the Northeast and Midwest was the 14th or even the 12th century. But it does not appear fueled by immigration and poverty, first by two waves that these gangs had the features of modern-day, serious of poor, largely white families from Europe. Seeking a street gangs.1 More structured gangs did not appear better life, the early immigrant groups mainly settled in until the early 1600s, when London was “terrorized by a urban areas and formed communities to join each other series of organized gangs calling themselves the Mims, in the economic struggle. Unfortunately, they had few Hectors, Bugles, Dead Boys … who found amusement in marketable skills. Difficulties in finding work and a place breaking windows, [and] demolishing taverns, [and they] to live and adjusting to urban life were equally common also fought pitched battles among themselves dressed among the European immigrants. -

Gang Recognition Guide

Gang Recognition Guide As gangs become an increasing issue in our society, education is the key to recognizing their activity and understanding what they are about. However, when discussing gangs, a working defi nition must be developed. Gangs are three or more individuals, using the same name, sign or symbol who commit criminal acts individually or as a group to further their agenda. The following information is not exhaustive in describing gangs and their background, but is a basic framework to educate concerned community members. Crips: This street gang originally started in South Central Los Angeles in the 1960’s. Stanley “Tookie” Williams met with Raymond Lee Washington to unite local gang members to battle neighboring street gangs. Today, the Crips are one of the largest and most violent gangs, involved in murders, robberies, drug dealing and many other criminal pursuits. Crips identify with the color blue. Their biggest rivals are the Bloods and disrespect in many ways - calling them “slobs”. Crips call themselves “Blood Killas” and cross the letter “b” out or leave it off altogether. Crips do not use the letters “ck” as it denotes “Crip Killer” and substitute it for “cc” (as in “kicc” for “kick”). While traditionally African-American, today’s Crip membership are multi-ethnic. Bloods: The Bloods were formed to compete against the Crips. Their origins stem from a Piru street gang (initially a Crip set) who broke away during an internal gang war and allied with other smaller street gangs to form the present day Bloods. Since the Bloods were originally outnumbered 3 to 1 by the Crips, they had to be more violent. -

Slide 1 Gang Awareness ______Supervising Gang Members in Rural ______Communities by Brian Parry ______

Slide 1 Gang Awareness ___________________________________ Supervising Gang Members In Rural ___________________________________ Communities By Brian Parry ___________________________________ ___________________________________ ___________________________________ ___________________________________ ___________________________________ Slide 2 ___________________________________ Training Objectives ___________________________________ • Identify scope of problem • Gang definitions and level of involvement ___________________________________ • Types of gangs • Characteristics and methods of ___________________________________ identification • Safety and supervision issues ___________________________________ • Collaboration and partnerships ___________________________________ ___________________________________ Slide 3 ___________________________________ Gang Perspectives ___________________________________ • Every instructor has a different perspective • 34 years of practical experience ___________________________________ • National perspective (NMGTF) • California gangs ___________________________________ • Professional organizations ___________________________________ ___________________________________ ___________________________________ Slide 4 ___________________________________ Collaborative Approach ___________________________________ • Societal problem • Requires collaborative effort ___________________________________ • Law enforcement/courts • Corrections ___________________________________ • Communities/schools/faith based groups -

2011 National Gang Threat Assessment

Federal Bureau of Investigation, National Gang Intelligence Center 2011 National Gang Threat Assessment [NOTE: This is a cached text version of the report obtained after the report was removed from the FBI website. It is missing all of the illustrations that appeared in the original report.] Preface The National Gang Intelligence Center (NGIC) prepared the 2011 National Gang Threat Assessment (NGTA) to examine emerging gang trends and threats posed by criminal gangs to communities throughout the United States. The 2011 NGTA enhances and builds on the gang-related trends and criminal threats identified in the 2009 assessment. It supports US Department of Justice strategic objectives 2.2 (to reduce the threat, incidence, and prevalence of violent crime) and 2.4 (to reduce the threat, trafficking, use, and related violence of illegal drugs). The assessment is based on federal, state, local, and tribal law enforcement and corrections agency intelligence, including information and data provided by the National Drug Intelligence Center (NDIC) and the National Gang Center. Additionally, this assessment is supplemented by information retrieved from open source documents and data collected through April 2011. Scope and Methodology In 2009, the NGIC released its second threat assessment on gang activity in the United States. The NGIC and its law enforcement partners documented increases in gang proliferation and migration nationwide and emerging threats. This report attempts to expand on these findings. Reporting and intelligence collected over the past two years have demonstrated increases in the number of gangs and gang members as law enforcement authorities nationwide continue to identify gang members and share information regarding these groups.