Commissioner for Standards in Public Life Case Report K/010

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

It-Tlettax-Il Leġiżlatura Pl 5604

IT-TLETTAX-IL LEĠIŻLATURA P.L. 5604 Dokument imqiegħed fuq il-Mejda tal-Kamra tad-Deputati fis-Seduta Numru 378 tas-26 ta’ Ottubru 2020 mill-Kap tal-Oppożizzjoni. ___________________________ Raymond Scicluna Skrivan tal-Kamra 10/26/2020 Malta, l'isola dell'impunita ecco chi vuole insabbiare Ia verita su Daphne - Ia Repubblica ABBONATI [ill = MENU Q_ CERCA Ia Repubblica ABBONATI QUOTIDIANO [ID (i} Esteri l\lalta, l'isola dell'impunita ecco chi v110le insabbiarc Ia Yerita su Daphne dai nostri inviati CARLO BONINI e GIULIANO FOSCHINI L 'indagine sui mandanti della giornalista uccisa e ferma, il govern a vuole aiTestare la sua fonte. Sei mesi dopa, il delitto Caruana Galizia e diventato un caso europeo 12 APRILE 2018 PUBBLICATO + Dl UN ANNO FA @ 4° MIN UTI Dl LETTURA f m ® LA VALLETTA - In cima alla antica Rocca, quella da cui tuona a salve il cannone della memoria due volte al giorno, c'e chi vuole che il volto in bianco e nero di Daphne Caruana Galizia non sorrida pili. Perche c'e me1noria e 1Tie1noria. E dunque, come accade con un fantasma della cui ombra si ha urgenza di liberarsi, da settimane mani zelanti rimuovono di notte cio che mani generose ricostruiscono di giorno: !'ultima traccia ancora tangibile dell'esistenza di Daphne. II suo memorial e. Foto in bianco e nero, in un letto di fiori e candele, alla base di una scultura marmorea, epigrafe della sua vita, spezzata da un'autobomba sei mesi fa, aile 14 e 58 minuti del16 Ottobre 2017, nella campagna di Bidnija.Nella furia iconoclasta di chi cancella c'e un riflesso condizionato e un'involontaria ammissione. -

Public Inquiry Into the Assassination of Daphne Caruana Galizia Written

Public Inquiry into the assassination of Daphne Caruana Galizia Written submission 31 March 2021 Authored by: Supported by: This submission has been coordinated by the Media Freedom Rapid Response (MFRR), which tracks, monitors and responds to violations of press and media freedom in EU Member States and Candidate Countries. This project provides legal and practical support, public advocacy and information to protect journalists and media workers. The MFRR is organised by a consortium led by the European Centre for Press and Media Freedom (ECPMF) including ARTICLE 19, the European Federation of Journalists (EFJ), Free Press Unlimited (FPU), the Institute for Applied Informatics at the University of Leipzig (InfAI), International Press Institute (IPI) and CCI/Osservatorio Balcani e Caucaso Transeuropa (OBCT). The project is co-funded by the European Commission. www.mfrr.eu Introduction 1. Our organisations, experts in freedom of expression and media freedom who work on research and advocacy on freedom of expression in Malta, are grateful for the opportunity to contribute our submission to this important process. Our submission will focus on the following areas of the Terms of Reference1: ● “To determine whether any wrongful action or omission by or within, any State entity facilitated the assassination or failed to prevent it. In particular whether (a) any State entity knew or ought to have known of, or caused, a real and immediate risk to Daphne Caruana Galizia’s life including from the criminal acts of a third party and (b) failed to take measures within the scope of its powers which, judged reasonably, it might have been expected to take in order to avoid that risk; ● “To determine whether the State has fulfilled and is fulfilling its positive obligation to take preventive operational measures to protect individuals whose lives are at risk from criminal acts in particular in the case of journalists.” The Establishment of the Public Inquiry 2. -

Daphne Caruana Galizia's Assassination and The

Restricted AS/Jur (2019) 23 20 May 2019 ajdoc23 2019 Committee on Legal Affairs and Human Rights Daphne Caruana Galizia’s assassination and the rule of law, in Malta and beyond: ensuring that the whole truth emerges Draft report Rapporteur: Mr Pieter OMTZIGT, the Netherlands, Group of the European People’s Party A. Preliminary draft resolution 1. Daphne Caruana Galizia, Malta’s best known and most widely-read investigative journalist, whose work focused on corruption amongst Maltese politicians and public officials, was assassinated by a car bomb close to her home on 16 October 2017. The response of the international community was immediate. Within the Council of Europe, the President of the Parliamentary Assembly, the Secretary General and the Commissioner for Human Rights all called for a thorough investigation of the murder. Ms Caruana Galizia’s murder and the continuing failure of the Maltese authorities to bring the suspected killers to trial or identify those who ordered her assassination raise serious questions about the rule of law in Malta. 2. Recalling the recent conclusions of the European Commission for Democracy through Law (Venice Commission) and the Group of States against Corruption (GRECO) concerning Malta, the Assembly notes the following: 2.1. The Prime Minister of Malta is predominant in Malta’s constitutional arrangements, sitting at the centre of political power, with extensive powers of appointment; 2.2. The Office of the Prime Minister has taken over responsibility for various areas of activity that present particular risks of money laundering, including on-line gaming, investment migration (‘golden passports’) and regulation of financial services, including cryptocurrencies; 2.3. -

Layout VGD Copy

The Voice oWfe tarhe foer thMe Graeatletr eMasltea Issue The Voice of the Maltese November 24, 2020 241 Fortnighttlly magazine A panoramic view of the Mellie ħa Parish Church and the surrounding area that in - cludes Malta’s most popular sandy beach, Mellie ħa Bay, otherwise known as G ħadira Bay in the background 2 The Voice of the Maltese Tuesday, November 24, 2020 Relationships - Churchill and Malta Busting the Myth The Winston Churchill bronze bust Paul Calleja (Part 1 of a at the Upper Barrakka Gardens in Valletta-Malta sculptured by well three-part series) known Maltese artist Vincent Apap hortly before Winston Churchill’s eightieth birthday, a But this truth is only a part of what is needed to adequately member of Malta’s Judiciary, Justice Montanaro-Gauci, assess Churchill’s worthiness of Malta’s post-war praises and wrote to him to inform him of fund-raising for his birth - sense of indebtedness. The missing truth is inconvenient, yet Sday gift from Malta. The gift was a bronze bust of Churchill, central to this assessment, in that it explains why crafted by eminent sculpturer, Vincent Apap. Today, this bust Churchill/Britain invested so much time, effort, resources and is found at the Upper Barrakka Gardens in Valletta. passion to defend Malta. Unsurprisingly, such information is Justice Montanaro-Gauci was generous with his praise of frequently omitted, or understated, by British historians, who Churchill, attributing his efforts for the salvation of Malta and write the bulk of publications on Malta’s wartime role. the Maltese during WW11. The Justice stated, “All people of Equally important of this missing truth, are explanations Malta recognise the great debt we owe to you …. -

It-Tlettax-Il Leġiżlatura P.L

IT-TLETTAX-IL LEĠIŻLATURA P.L. 6551 Dokument imqiegħed fuq il-Mejda tal-Kamra tad-Deputati fis-Seduta Numru 458 tal-10 ta’ Mejju 2021 mill-Onor. Glenn Bedingfield, MP. ___________________________ Raymond Scicluna Skrivan tal-Kamra The @ Ads by Google Srop seeing this ad Why this ad? (;) The Costanza defence Ranier Fsadni Prime Minister Robert Abela misled parliament on expenditure on public relations firms Caroline Muscat Contrary to what Prime Minister Robert Abela told parl iament, the Office of the Prime Minister (OPM) Keep your enemies close appears to have spent a significant amount of Blanche Gatt taxpayers' money on local and international public relations Consultancy, an analysis of information published in the Government Gazette shows. In February, PN MP Jason Azzopa rdi asked Abela to state and list exactly how much money has been spent by the OPM on public relations (PR) and communications consultancies si nce 2013, when the Labour Parry came to power. Political responsibility is the new serenity Ryan Munlock <D x Photography sorne cornpames Still Believe that Media Marketing Is Wasted Money. Is that You? Nisga Abela replied last week that no entit:y or department that falls under the remit of the Prime Minister's office has spent any money on such services. But according to information publicly available in the Government Gazette and past PQs analysed by The Shift, betvveen 2013 and the present day, the OPM spent hundreds of thousands on Consultancy services to some of the most well-known PR and advisory consultancies in the world. The hundreds of thousands spent by the OPM is, in turn, a mere fraction of the rota! spend by the government on PR, communications and si milar marketing related services over the years. -

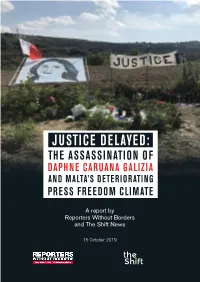

A Report by Reporters Without Borders and the Shift News

A report by Reporters Without Borders and The Shift News 15 October 2019 CONTENTSI Acknowledgements 2 Executive Summary 3 1 - Chapter One: An unthinkable act 4 2 - Chapter Two: Investigating the assassination 7 3 - Chapter Three: The magisterial inquiry and police interference 20 4 - Chapter Four: Malta’s deteriorating press freedom climate 25 5 - Chapter Five: The international reaction 35 6 - Chapter Six: An urgent need for an independent and impartial public inquiry 42 Concluding observations and recommendations 46 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This publication is a joint report of Reporters Without Borders (RSF) and The Shift News, researched and co-authored by RSF UK Bureau Director Rebecca Vincent and The Shift News Founder and Editor Caroline Muscat. Editorial support was provided by RSF Editor-in-Chief Bertin Leblanc and the Head of RSF’s EU-Balkans Desk, Pauline Adès-Mével, with proofreading done by RSF UK Programme Assistant Katie Fallon. This report has been published with the kind financial support of the Justice for Journalists Foundation. 2 EXECUTIVE SUMMARYN On 16 October 2017, journalist Daphne Caruana Galizia was assassinated by a car bomb that detonated near her home in Bidnija, Malta – an act that was previously unthinkable in an EU state. Caruana Galizia was the country’s most prominent journalist, known for her courageous investigative reporting exposing official corruption in Malta and beyond, including her reporting on the Panama Papers. A full two years on, there has still been no justice for this heinous assassination, which has shed light on broader systemic failings with regard to Malta’s press freedom climate, rule of law, and democratic checks and balances. -

Annual-Report-2017-English-Version.Pdf

House of Representatives Annual Report 2017 House of Representatives Parliament of Malta Freedom Square Valletta Tel: +356 2559 6000 Website: www.parlament.mt Printed at the Government Printing Press Photos: Office of the Speaker and Department of Information ‘There shall be a Parliament of Malta which shall consist of the President and a House of Representatives’. [Article 51 of the Constitution of Malta] ‘Subject to the provisions of this Constitution, Parliament may make laws for the peace, order and good government of Malta in conformity with full respect for human rights, generally accepted principles of international law and Malta’s international and regional obligations in particular those assumed by the treaty of accession to the European Union signed in Athens on the 16th April, 2003’. [Article 65 (1) of the Constitution of Malta] Table of Contents FOREWORD............................................................................................................................................................. 3 1. HOUSE BUSINESS ................................................................................................................................................ 5 1.1 Overview ........................................................................................................................................................... 5 1.1.1 New initiatives taken by Parliament in 2017......................................................................................... 5 1.1.2 Composition of Parliament .................................................................................................................... -

A MISSION to INFORM Daphne Caruana Galizia Speaks Out

A MISSION TO INFORM Daphne Caruana Galizia speaks out PREMS 092120 ENG The last recorded interview with Daphne Caruana Galizia 6 October 2017 Edited by Marilyn Clark and William Horsley A MISSION TO INFORM Daphne Caruana Galizia speaks out The last recorded interview with Daphne Caruana Galizia 6 October 2017 Abridged version Editors: Marilyn Clark William Horsley Council of Europe The opinions expressed in this work are the responsibility of the interviewee and not of the authors, editors or Council of Europe and do not necessarily reflect the official policy of the Council of Europe. All requests concerning the reproduction or translation of all or part of this document should be addressed to the Directorate of Communications (F-67075 Strasbourg Cedex or [email protected]). Back cover quotations by: All other correspondence concerning Mr Harlem Désir, Fourth OSCE Representative on this document should be addressed Freedom of the Media. to the Media and Internet Governance Statement available at www.osce.org Information Society Department. The UN Special Rapporteurs: Ms Agnes Callamard, Special Rapporteur on extrajudicial, summary or Cover and layout: arbitrary executions; Mr Michel Forst, Special Documents and Publications Production Rapporteur on the situation of human rights Department (SPDP), Council of Europe defenders; Mr Juan Pablo Bohoslavsky, Independent Expert on the effects of foreign debt and human Cover Photo: ©Pippa Zammit Cutajar rights; and Mr David Kaye, Special Rapporteur on the promotion and protection of the right to freedom ©Council of Europe, October 2020 of opinion and expression. Printed at the Council of Europe Statement available at www.ohchr.org. -

How They Voted on Gay Rights

NEWS MaltaToday, Sunday, 10 May 2009 7 Four MEP candidates sign gay rights pledge James Debono How they voted on gay rights FOUR MEP candidates have signed a ten-point election pledge by the International Lesbian-Gay Association of Europe (ILGA) to combat dis- crimination based on sexual orientation, gender identity and gender expression. The candidates are Altern- attiva Demorakita candidates Arnold Cassola and Yvonne Busuttil Casa Bedingfi eld Grech Montalto Muscat Ebejer Arqueros, Labour can- didate Sharon Ellul Bonici Buitenweg report (April 2009) Abs / + + / * and Alleanza Liberali candi- Catania report (Jan 2009) – – Abs Abs Abs * date John Zammit. They joined 266 MEP can- Lynne report (May 2008) Abs Abs * + – / didates from all over Europe who signed the declaration. Resolution on homophobia (April 2007) Abs Abs * + + + The declaration makes no Resolution on homophobic violence (June 2006) Abs Abs * + + + specific reference to gay mar- riages or adoptions, but calls Zdonoka report (June 2006) – – * + + / on MEPs to support an “inclu- sive definition of the family” Resolution on homophobia (Jan 2006) – Abs * + / + which recognises the diversi- ty of family relationships, and Legend : Abs Abstain, / Not present for the vote, + In favour, – Against to ensure the needs of LGBT (lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans- * Joseph Muscat was elected PL leader in September 2008 and his seat was taken by Glenn Bedingfi eld sexual) families are increas- ingly reflected in EU policy and in its social legislation, including the parental leave Louis Grech in EU law, by their adequate vote once. The two MEPs did stained on the Catania report directive. coverage in future gender not vote in favour of any of on the human rights situa- In a comment on ILGA’s equality laws and policy. -

It-Tlettax-Il Leġiżlatura Pl 2543

IT-TLETTAX-IL LEĠIŻLATURA P.L. 2543 Dokument imqiegħed fuq il-Mejda tal-Kamra tad-Deputati fis-Seduta Numru 169 tad-19 ta’ Novembru 2018 mill-Ispeaker, l-Onor. Anġlu Farrugia. ___________________________ Raymond Scicluna Skrivan tal-Kamra Second Session of the International Parliament for Tolerance and Peace 15 - 16 November 2018 Tirana, Albania Hon Anglu Farrugia, Speaker Hon Glenn Bedingfield, MP Parliamentary Delegation Report to the House of Representatives. Date: 14th -17th November 2018 Venue: Tirana, Albania r Maltese delegation: Honourable Anglu Farrugia, President of the House of Representatives, Parliament of Malta Honourable Glenn Bedingfield, Government Member Ms Karen Mama, Research Analyst, House of Representatives Programme: At the invitation of the President of the International Parliament for Tolerance and Peace, Honourable Taulant Balla, the Speaker of the House of Representatives, Parliament of Malta, the Honourable Anglu Farrugia, participated at the Second Session of the International Parliament for Tolerance and Peace, plenary session, which was held at the House of Representatives, Parliament of Albania, in Tirana. Report prepared by the Honourable Speaker of the House of Representatives, Parliament of Malta. Between Thursday 15U1 of November and Friday the 16th of November, I led a parliamentary delegation to the 2nd Session of the International Parliament for Tolerance and Peace. The meeting took place in Tirana, Albania and included the participation of over 30 countries from across the globe. I was invited to give one of the opening speeches and together with President Al-Jarwan to sign the declaration establishing the foundation of the IPTP. The other members of the delegation were Honourable Glenn Bedingfield from the Government side and Ms Karen Mamo, Research Analyst. -

Bord Ta' Inkjesta- Daphne Caruana Galizia

Rapport tal-Inkjesta Pubblika Daphne Caruana Galizia Ġurnalista Assassinata fis-16 ta’ Ottubru 2017 Preżentat lil Onor. Prim Ministru Dr. Robert Abela fid-29 ta’ Lulju 2021 Chairman - Imħallef Michael Mallia Membri - Prim Imħallef Emeritus Joseph Said Pullicino Onor. Imħallef Abigail Lofaro Werrej Daħla .................................................................................................................... 3 Taqsima I - Preliminari ......................................................................................... 7 Taqsima II – Osservazzjonijiet Ġenerali ............................................................. 23 Kap 1 Dwar in-natura u l-limiti tat-termini ta’ referenza ..................................... 25 Kap 2 Il-provi rilevanti għall-Inkjesta.................................................................... 53 Kap 3 Il-valur tal-ġurnaliżmu investigattiv f’demokrazija parteċipattiva ............. 61 Kap 4 Kultura ta’ Impunità u l-Poter .................................................................... 89 Kap 5 Stil ta’ tmexxija li iffavorixxa l-impunità ................................................... 114 Kap 6 L-eżerċizzju tal-poter u l-assassinju .......................................................... 147 Kap 7 Mill-pubblikazzjoni tal-Panama Papers u wara Jeskala l-livell ta’ riskju 185 Taqsima III L-ewwel terminu ta’ referenza ........................................................................ 231 Taqsima IV It-tieni terminu ta’ referenza .......................................................................... -

Cover Feb15 2009.Pdf

MALTA’S INDEPENDENT VOICE maltatoday €0.90 Sunday, 15 February 2009 – issue 484 • www.maltatoday.com.mt PN ‘super-mole’ informs Labour of what PM is doing A veritable rebellion from Nationalist Gonzi did not want to give Joseph Mus- Sources fromm the OOfficeffice hihhiss party over the MMistra scandal in backbenchers and former ministers last cat an even bigger winning card before of the Primeme MiniMinisterster thtthee lastlast eelection.lection Wednesday forced the prime minister the European Parliament and local coun- sources told MMaltaTodayaltaToday ThThee backbencherbackb launched into retreat over the proposed €16 mil- cil elections. that Gonzi waswas furiousfuriouss hihhiss owownn personal cru- lion underground extension for St John’s In an attempt to avoid any leaks to the at yet another leakleak ffromromm ssasadede aagainstg the EU- Co-Cathedral. Labour Party and the press, Gonzi decid- within the parliamen-rliamen- ffufundednded project to house Lawrence Gonzi was faced with no al- ed to call a meeting just four hours before tary group. tththee Cathedral’sCat Goblin ternative but to backtrack over the al- parliament convened to discuss the mo- Wednesday’sa y’s ttatapestriespestr in an un- location of millions in EU funds for the tion on Wednesday evening. parliamentaryt ary deddergroundrgro museum, Cathedral’s underground museum, as he But the ‘permanent’ presence of a super- meeting was not bbubutt PPN sources say faced a rebellion from Jeffrey Pullicino mole in the PN parliamentary group, led attended by JeJef-f-- hhihiss ooppositionp stems Orlando, Censu Galea, Ninu Zammit, Labour to issue the flash news of the par- frey Pullicinocinoo fromffrom his antagonism Jesmond Mugliett and Robert Arrigo.