Functional Regression Method for Whole Genome Eqtl Epistasis Analysis with Sequencing Data Kelin Xu1,2, Li Jin1 and Momiao Xiong1,3,4*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“A Very Stinking Herbe” Is Cilantro Love/Hate a Genetic Trait? So Fresh Or So Clean? Methods Results and Discussion Referenc

A Genetic Variant Near Olfactory Receptor Genes Associates With Cilantro Preference S. Wu, J.Y. Tung, A.B. Chowdry, A.K. Kiefer, J.L. Mountain, N. Eriksson 23andMe, Inc., Mountain View, CA “A very stinking herbe”! Many people love the taste of fresh cilantro (Coriandrum sativum, also called coriander), while Oh, coriander.! others despise it with every fiber of their being. The debate has raged for centuries. Pliny extolled If "pure evil# had a taste?! its “refreshing” properties, a medieval herbalist claimed that the leaves had a “venomous quality,” It would taste like you.! by SilverSpoon at and, more recently, beloved culinary icon Julia Child opined that cilantro had “kind of a dead taste” IHateCilantro.com! and that she would “pick it out if [she] saw it and throw it on the floor.”! So fresh or so clean?! Is cilantro love/hate a genetic trait?! Cilantro"s dual nature may lie in its key aroma components, which consist of It is not known why cilantro is so differentially perceived. Cilantro various aldehydes. The unsaturated aldehydes (mostly decanal and preference varies with ancestry and may be influenced by dodecanal) are described as fruity, green, and pungent; the (E)-2-alkenals exposure. Genetic factors are also thought to play a role but to as soapy, fatty, pungent, and “like cilantro.” Of the many descriptors that date no studies have found genetic variants influencing cilantro “haters” use, soapy is the most common.! taste preference. ! Methods! Results and discussion! We conducted the first-ever genome-wide association study of cilantro preference. Participants were drawn from the more than 180,000 genotyped customers of 23andMe, Inc., a consumer genetics company.! Phenotype data collection! Participants reported their age and answered Figure 1. -

Genetic Variation Across the Human Olfactory Receptor Repertoire Alters Odor Perception

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/212431; this version posted November 1, 2017. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY 4.0 International license. Genetic variation across the human olfactory receptor repertoire alters odor perception Casey Trimmer1,*, Andreas Keller2, Nicolle R. Murphy1, Lindsey L. Snyder1, Jason R. Willer3, Maira Nagai4,5, Nicholas Katsanis3, Leslie B. Vosshall2,6,7, Hiroaki Matsunami4,8, and Joel D. Mainland1,9 1Monell Chemical Senses Center, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA 2Laboratory of Neurogenetics and Behavior, The Rockefeller University, New York, New York, USA 3Center for Human Disease Modeling, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, North Carolina, USA 4Department of Molecular Genetics and Microbiology, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, North Carolina, USA 5Department of Biochemistry, University of Sao Paulo, Sao Paulo, Brazil 6Howard Hughes Medical Institute, New York, New York, USA 7Kavli Neural Systems Institute, New York, New York, USA 8Department of Neurobiology and Duke Institute for Brain Sciences, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, North Carolina, USA 9Department of Neuroscience, University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA *[email protected] ABSTRACT The human olfactory receptor repertoire is characterized by an abundance of genetic variation that affects receptor response, but the perceptual effects of this variation are unclear. To address this issue, we sequenced the OR repertoire in 332 individuals and examined the relationship between genetic variation and 276 olfactory phenotypes, including the perceived intensity and pleasantness of 68 odorants at two concentrations, detection thresholds of three odorants, and general olfactory acuity. -

Identification of Genetic Factors Underpinning Phenotypic Heterogeneity in Huntington’S Disease and Other Neurodegenerative Disorders

Identification of genetic factors underpinning phenotypic heterogeneity in Huntington’s disease and other neurodegenerative disorders. By Dr Davina J Hensman Moss A thesis submitted to University College London for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Neurodegenerative Disease Institute of Neurology University College London (UCL) 2020 1 I, Davina Hensman Moss confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. Collaborative work is also indicated in this thesis. Signature: Date: 2 Abstract Neurodegenerative diseases including Huntington’s disease (HD), the spinocerebellar ataxias and C9orf72 associated Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis / Frontotemporal dementia (ALS/FTD) do not present and progress in the same way in all patients. Instead there is phenotypic variability in age at onset, progression and symptoms. Understanding this variability is not only clinically valuable, but identification of the genetic factors underpinning this variability has the potential to highlight genes and pathways which may be amenable to therapeutic manipulation, hence help find drugs for these devastating and currently incurable diseases. Identification of genetic modifiers of neurodegenerative diseases is the overarching aim of this thesis. To identify genetic variants which modify disease progression it is first necessary to have a detailed characterization of the disease and its trajectory over time. In this thesis clinical data from the TRACK-HD studies, for which I collected data as a clinical fellow, was used to study disease progression over time in HD, and give subjects a progression score for subsequent analysis. In this thesis I show blood transcriptomic signatures of HD status and stage which parallel HD brain and overlap with Alzheimer’s disease brain. -

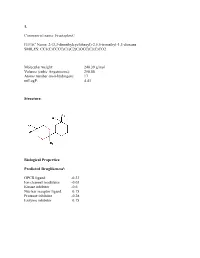

Sean Raspet – Molecules

1. Commercial name: Fructaplex© IUPAC Name: 2-(3,3-dimethylcyclohexyl)-2,5,5-trimethyl-1,3-dioxane SMILES: CC1(C)CCCC(C1)C2(C)OCC(C)(C)CO2 Molecular weight: 240.39 g/mol Volume (cubic Angstroems): 258.88 Atoms number (non-hydrogen): 17 miLogP: 4.43 Structure: Biological Properties: Predicted Druglikenessi: GPCR ligand -0.23 Ion channel modulator -0.03 Kinase inhibitor -0.6 Nuclear receptor ligand 0.15 Protease inhibitor -0.28 Enzyme inhibitor 0.15 Commercial name: Fructaplex© IUPAC Name: 2-(3,3-dimethylcyclohexyl)-2,5,5-trimethyl-1,3-dioxane SMILES: CC1(C)CCCC(C1)C2(C)OCC(C)(C)CO2 Predicted Olfactory Receptor Activityii: OR2L13 83.715% OR1G1 82.761% OR10J5 80.569% OR2W1 78.180% OR7A2 77.696% 2. Commercial name: Sylvoxime© IUPAC Name: N-[4-(1-ethoxyethenyl)-3,3,5,5tetramethylcyclohexylidene]hydroxylamine SMILES: CCOC(=C)C1C(C)(C)CC(CC1(C)C)=NO Molecular weight: 239.36 Volume (cubic Angstroems): 252.83 Atoms number (non-hydrogen): 17 miLogP: 4.33 Structure: Biological Properties: Predicted Druglikeness: GPCR ligand -0.6 Ion channel modulator -0.41 Kinase inhibitor -0.93 Nuclear receptor ligand -0.17 Protease inhibitor -0.39 Enzyme inhibitor 0.01 Commercial name: Sylvoxime© IUPAC Name: N-[4-(1-ethoxyethenyl)-3,3,5,5tetramethylcyclohexylidene]hydroxylamine SMILES: CCOC(=C)C1C(C)(C)CC(CC1(C)C)=NO Predicted Olfactory Receptor Activity: OR52D1 71.900% OR1G1 70.394% 0R52I2 70.392% OR52I1 70.390% OR2Y1 70.378% 3. Commercial name: Hyperflor© IUPAC Name: 2-benzyl-1,3-dioxan-5-one SMILES: O=C1COC(CC2=CC=CC=C2)OC1 Molecular weight: 192.21 g/mol Volume -

Genome-Wide Analysis Distinguishes Hyperglycemia Regulated Epigenetic Signatures of Primary Vascular Cells

Downloaded from genome.cshlp.org on September 28, 2021 - Published by Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press Research Genome-wide analysis distinguishes hyperglycemia regulated epigenetic signatures of primary vascular cells Luciano Pirola,1,8 Aneta Balcerczyk,1,8 Richard W. Tothill,2 Izhak Haviv,3 Antony Kaspi,1 Sebastian Lunke,1 Mark Ziemann,1,2 Tom Karagiannis,1 Stephen Tonna,1 Adam Kowalczyk,4 Bryan Beresford-Smith,4 Geoff Macintyre,4 Ma Kelong,5 Zhang Hongyu,5 Jingde Zhu,5 and Assam El-Osta1,2,6,7,9 1Epigenetics in Human Health and Disease Laboratory, Baker IDI Heart and Diabetes Institute, The Alfred Medical Research and Education Precinct, Melbourne, Victoria 3004, Australia; 2Epigenomic Profiling Facility, Baker IDI Heart and Diabetes Institute, The Alfred Medical Research and Education Precinct, Melbourne, Victoria 3004, Australia; 3Bioinformatics & Systems Integration, Baker IDI Heart and Diabetes Institute, The Alfred Medical Research and Education Precinct, Melbourne, Victoria 3004, Australia; 4NICTA Victoria Research Laboratory, Department of Electrical and Electronic Engineering, The University of Melbourne, Victoria 3010, Australia; 5Shanghai Cancer Institute, Jiaotong University, Shanghai 200032, China; 6Department of Pathology, The University of Melbourne, Victoria 3010, Australia; 7Faculty of Medicine, Monash University, Victoria 3800, Australia Emerging evidence suggests that poor glycemic control mediates post-translational modifications to the H3 histone tail. We are only beginning to understand the dynamic role of some of the diverse epigenetic changes mediated by hyper- glycemia at single loci, yet elevated glucose levels are thought to regulate genome-wide changes, and this still remains poorly understood. In this article we describe genome-wide histone H3K9/K14 hyperacetylation and DNA methylation maps conferred by hyperglycemia in primary human vascular cells. -

Genetic Characterization of Greek Population Isolates Reveals Strong Genetic Drift at Missense and Trait-Associated Variants

ARTICLE Received 22 Apr 2014 | Accepted 22 Sep 2014 | Published 6 Nov 2014 DOI: 10.1038/ncomms6345 OPEN Genetic characterization of Greek population isolates reveals strong genetic drift at missense and trait-associated variants Kalliope Panoutsopoulou1,*, Konstantinos Hatzikotoulas1,*, Dionysia Kiara Xifara2,3, Vincenza Colonna4, Aliki-Eleni Farmaki5, Graham R.S. Ritchie1,6, Lorraine Southam1,2, Arthur Gilly1, Ioanna Tachmazidou1, Segun Fatumo1,7,8, Angela Matchan1, Nigel W. Rayner1,2,9, Ioanna Ntalla5,10, Massimo Mezzavilla1,11, Yuan Chen1, Chrysoula Kiagiadaki12, Eleni Zengini13,14, Vasiliki Mamakou13,15, Antonis Athanasiadis16, Margarita Giannakopoulou17, Vassiliki-Eirini Kariakli5, Rebecca N. Nsubuga18, Alex Karabarinde18, Manjinder Sandhu1,8, Gil McVean2, Chris Tyler-Smith1, Emmanouil Tsafantakis12, Maria Karaleftheri16, Yali Xue1, George Dedoussis5 & Eleftheria Zeggini1 Isolated populations are emerging as a powerful study design in the search for low-frequency and rare variant associations with complex phenotypes. Here we genotype 2,296 samples from two isolated Greek populations, the Pomak villages (HELIC-Pomak) in the North of Greece and the Mylopotamos villages (HELIC-MANOLIS) in Crete. We compare their genomic characteristics to the general Greek population and establish them as genetic isolates. In the MANOLIS cohort, we observe an enrichment of missense variants among the variants that have drifted up in frequency by more than fivefold. In the Pomak cohort, we find novel associations at variants on chr11p15.4 showing large allele frequency increases (from 0.2% in the general Greek population to 4.6% in the isolate) with haematological traits, for example, with mean corpuscular volume (rs7116019, P ¼ 2.3 Â 10 À 26). We replicate this association in a second set of Pomak samples (combined P ¼ 2.0 Â 10 À 36). -

A Genetic Variant Near Olfactory Receptor Genes Influences Cilantro Preference

A genetic variant near olfactory receptor genes influences cilantro preference Nicholas Eriksson1,*, Shirley Wu1, Chuong B. Do1, Amy K. Kiefer1, Joyce Y. Tung1, Joanna L. Mountain1, David A. Hinds1, and Uta Francke1 123andMe, Inc., Mountain View, CA USA *[email protected] September 11, 2012 Abstract ponent to cilantro taste perception and suggest that cilantro dislike may stem from genetic variants in ol- The leaves of the Coriandrum sativum plant, known factory receptors. We propose that OR6A2 may be as cilantro or coriander, are widely used in many the olfactory receptor that contributes to the detec- cuisines around the world. However, far from being tion of a soapy smell from cilantro in European pop- a benign culinary herb, cilantro can be polarizing| ulations. many people love it while others claim that it tastes or smells foul, often like soap or dirt. This soapy or pungent aroma is largely attributed to several Background aldehydes present in cilantro. Cilantro preference is suspected to have a genetic component, yet to date The Coriandrum sativum plant has been cultivated nothing is known about specific mechanisms. Here since at least the 2nd millennium BCE [1]. Its fruits we present the results of a genome-wide association (commonly called coriander seeds) and leaves (called study among 14,604 participants of European ances- cilantro or coriander) are important components of try who reported whether cilantro tasted soapy, with many cuisines. In particular, South Asian cuisines replication in a distinct set of 11,851 participants who use both the leaves and the seeds prominently, and declared whether they liked cilantro. -

A Genome-Wide Association Study

Identification of genetic variants associated with Huntington’s disease progression: a genome-wide association study Davina J Hensman Moss* 1, MBBS, Antonio F. Pardiñas* 2, PhD, Prof Douglas Langbehn 3, PhD, Kitty Lo 4, PhD, Prof Blair R. Leavitt 5, MD,CM, Prof Raymund Roos 6, MD, Prof Alexandra Durr 7, MD, Prof Simon Mead 8, PhD, the REGISTRY investigators and the TRACK-HD investigators, Prof Peter Holmans 2, PhD, Prof Lesley Jones §2 , PhD, Prof Sarah J Tabrizi §1 , PhD. * These authors contributed equally to this work § These authors contributed equally to this work 1) UCL Huntington’s Disease Centre, UCL Institute of Neurology, Dept. of Neurodegenerative Disease, London, UK 2) MRC Centre for Neuropsychiatric Genetics and Genomics, Cardiff University, Cardiff, UK 3) University of Iowa Carver College of Medicine, Dept. of Psychiatry and Biostatistics, Iowa, USA 4) UCL Genetics Institute, Div. of Biosciences, London, UK 5) Centre for Molecular Medicine and Therapeutics, Department of Medical Genetics, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada 6) Department of Neurology, Leiden University Medical Centre, Leiden, Netherlands 7) ICM and APHP Department of Genetics, Inserm U 1127, CNRS UMR 7225, Sorbonne Universités, UPMC Univ Paris 06 UMR S 1127, Pitié- Salpêtrière University Hospital, Paris, France 8) MRC Prion Unit, UCL Institute of Neurology, London, UK Corresponding authors: Sarah J Tabrizi at [email protected] Lesley Jones at [email protected] 1 ABSTRACT Background Huntington’s disease (HD) is a fatal inherited neurodegenerative disease, caused by a CAG repeat expansion in HTT . Age at onset (AAO) has been used as a quantitative phenotype in genetic analysis looking for HD modifiers, but is hard to define and not always available. -

The Hypothalamus As a Hub for SARS-Cov-2 Brain Infection and Pathogenesis

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.06.08.139329; this version posted June 19, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. The hypothalamus as a hub for SARS-CoV-2 brain infection and pathogenesis Sreekala Nampoothiri1,2#, Florent Sauve1,2#, Gaëtan Ternier1,2ƒ, Daniela Fernandois1,2 ƒ, Caio Coelho1,2, Monica ImBernon1,2, Eleonora Deligia1,2, Romain PerBet1, Vincent Florent1,2,3, Marc Baroncini1,2, Florence Pasquier1,4, François Trottein5, Claude-Alain Maurage1,2, Virginie Mattot1,2‡, Paolo GiacoBini1,2‡, S. Rasika1,2‡*, Vincent Prevot1,2‡* 1 Univ. Lille, Inserm, CHU Lille, Lille Neuroscience & Cognition, DistAlz, UMR-S 1172, Lille, France 2 LaBoratorY of Development and PlasticitY of the Neuroendocrine Brain, FHU 1000 daYs for health, EGID, School of Medicine, Lille, France 3 Nutrition, Arras General Hospital, Arras, France 4 Centre mémoire ressources et recherche, CHU Lille, LiCEND, Lille, France 5 Univ. Lille, CNRS, INSERM, CHU Lille, Institut Pasteur de Lille, U1019 - UMR 8204 - CIIL - Center for Infection and ImmunitY of Lille (CIIL), Lille, France. # and ƒ These authors contriButed equallY to this work. ‡ These authors directed this work *Correspondence to: [email protected] and [email protected] Short title: Covid-19: the hypothalamic hypothesis 1 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.06.08.139329; this version posted June 19, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. -

Supplementary Table S4

Supplementary Table 4 - Patient P10 Heat maps of mutations and gene expression for patients with three or more tumor sample analyzed. P10 SNV Allele frequency Log2(FPKM+1) GeneSymbol S1 S5 S8 S1 S5 S8 S1 S5 S8 Ref KDM6A* 1 1 1 0.82 0.87 0.64 2.36 2.28 2.22 3.01 UBAP2L 1 1 1 0.63 0.58 0.47 4.72 5.10 5.33 4.78 SLC12A5 1 1 1 0.60 0.32 0.29 0.05 0.01 0.00 0.02 KDM6A FMO1 1 1 1 0.59 0.56 0.41 0.23 0.04 0.40 0.14 MCC 1 1 1 0.58 0.46 0.49 4.33 5.29 4.99 4.54 3.50 MCAM 1 1 1 0.57 0.38 0.38 2.73 2.60 3.95 3.11 CCDC60 1 1 1 0.52 0.47 0.36 0.06 0.01 0.00 1.58 3.00 RALYL 1 1 1 0.52 0.25 0.24 0.03 0.03 0.00 0.15 2.50 AGXT 1 1 1 0.50 0.40 0.29 0.01 0.00 0.00 0.04 FAM209B 1 1 1 0.46 0.33 0.35 0.01 0.02 0.02 0.09 2.00 MYO7B 1 1 1 0.45 0.52 0.34 0.01 0.00 0.01 0.13 PPARG 1 1 1 0.45 0.48 0.34 5.55 5.93 5.70 5.92 1.50 MUC4 1 1 1 0.44 0.42 0.29 0.17 0.12 0.05 0.67 Log2(FPKM+1) HRAS** 1 1 1 0.44 0.39 0.20 4.32 4.75 4.55 3.28 1.00 MIA3 1 1 1 0.39 0.38 0.19 5.30 5.35 5.15 4.70 0.50 CLTC# 1 1 1 0.39 0.39 0.37 5.57 5.93 5.81 6.05 CEP152 1 1 1 0.38 0.43 0.17 3.28 2.78 3.25 2.14 0.00 DDC 1 1 1 0.38 0.34 0.29 0.01 0.01 0.00 0.12 S1 S5 S8 Ref HERC2 1 1 1 0.38 0.36 0.25 3.60 3.77 3.09 3.14 SEMA3D 1 1 1 0.37 0.51 0.26 0.38 0.60 0.53 2.83 ZNF320 1 1 1 0.34 0.41 0.22 4.14 4.25 4.08 4.07 HRAS ERBB3# 1 1 1 0.34 0.39 0.26 5.52 5.85 5.60 4.69 KSR2 1 1 1 0.33 0.39 0.27 0.75 1.17 0.65 0.97 5.00 TRERF1 1 1 1 0.32 0.42 0.27 2.10 2.45 2.25 2.63 4.50 COG4 1 1 1 0.31 0.36 0.27 3.78 4.06 4.12 3.58 4.00 LPAR5 1 1 1 0.31 0.43 0.24 0.92 1.03 0.47 1.17 3.50 PRTN3 1 1 1 0.30 0.05 0.02 -

Gnomad Lof Supplement

1 gnomAD supplement gnomAD supplement 1 Data processing 4 Alignment and read processing 4 Variant Calling 4 Coverage information 5 Data processing 5 Sample QC 7 Hard filters 7 Supplementary Table 1 | Sample counts before and after hard and release filters 8 Supplementary Table 2 | Counts by data type and hard filter 9 Platform imputation for exomes 9 Supplementary Table 3 | Exome platform assignments 10 Supplementary Table 4 | Confusion matrix for exome samples with Known platform labels 11 Relatedness filters 11 Supplementary Table 5 | Pair counts by degree of relatedness 12 Supplementary Table 6 | Sample counts by relatedness status 13 Population and subpopulation inference 13 Supplementary Figure 1 | Continental ancestry principal components. 14 Supplementary Table 7 | Population and subpopulation counts 16 Population- and platform-specific filters 16 Supplementary Table 8 | Summary of outliers per population and platform grouping 17 Finalizing samples in the gnomAD v2.1 release 18 Supplementary Table 9 | Sample counts by filtering stage 18 Supplementary Table 10 | Sample counts for genomes and exomes in gnomAD subsets 19 Variant QC 20 Hard filters 20 Random Forest model 20 Features 21 Supplementary Table 11 | Features used in final random forest model 21 Training 22 Supplementary Table 12 | Random forest training examples 22 Evaluation and threshold selection 22 Final variant counts 24 Supplementary Table 13 | Variant counts by filtering status 25 Comparison of whole-exome and whole-genome coverage in coding regions 25 Variant annotation 30 Frequency and context annotation 30 2 Functional annotation 31 Supplementary Table 14 | Variants observed by category in 125,748 exomes 32 Supplementary Figure 5 | Percent observed by methylation. -

Us 2018 / 0305689 A1

US 20180305689A1 ( 19 ) United States (12 ) Patent Application Publication ( 10) Pub . No. : US 2018 /0305689 A1 Sætrom et al. ( 43 ) Pub . Date: Oct. 25 , 2018 ( 54 ) SARNA COMPOSITIONS AND METHODS OF plication No . 62 /150 , 895 , filed on Apr. 22 , 2015 , USE provisional application No . 62/ 150 ,904 , filed on Apr. 22 , 2015 , provisional application No. 62 / 150 , 908 , (71 ) Applicant: MINA THERAPEUTICS LIMITED , filed on Apr. 22 , 2015 , provisional application No. LONDON (GB ) 62 / 150 , 900 , filed on Apr. 22 , 2015 . (72 ) Inventors : Pål Sætrom , Trondheim (NO ) ; Endre Publication Classification Bakken Stovner , Trondheim (NO ) (51 ) Int . CI. C12N 15 / 113 (2006 .01 ) (21 ) Appl. No. : 15 /568 , 046 (52 ) U . S . CI. (22 ) PCT Filed : Apr. 21 , 2016 CPC .. .. .. C12N 15 / 113 ( 2013 .01 ) ; C12N 2310 / 34 ( 2013. 01 ) ; C12N 2310 /14 (2013 . 01 ) ; C12N ( 86 ) PCT No .: PCT/ GB2016 /051116 2310 / 11 (2013 .01 ) $ 371 ( c ) ( 1 ) , ( 2 ) Date : Oct . 20 , 2017 (57 ) ABSTRACT The invention relates to oligonucleotides , e . g . , saRNAS Related U . S . Application Data useful in upregulating the expression of a target gene and (60 ) Provisional application No . 62 / 150 ,892 , filed on Apr. therapeutic compositions comprising such oligonucleotides . 22 , 2015 , provisional application No . 62 / 150 ,893 , Methods of using the oligonucleotides and the therapeutic filed on Apr. 22 , 2015 , provisional application No . compositions are also provided . 62 / 150 ,897 , filed on Apr. 22 , 2015 , provisional ap Specification includes a Sequence Listing . SARNA sense strand (Fessenger 3 ' SARNA antisense strand (Guide ) Mathew, Si Target antisense RNA transcript, e . g . NAT Target Coding strand Gene Transcription start site ( T55 ) TY{ { ? ? Targeted Target transcript , e .