This Document IS a HOLDING of the ARCHIVES SECTION LIBRARY SERVICES FORT LEAVENWORTH, KANSAS DOCUMENT NO.N Li-- COPY NO

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ABSTRACT Title of Document: the FURTHEST

ABSTRACT Title of Document: THE FURTHEST WATCH OF THE REICH: NATIONAL SOCIALISM, ETHNIC GERMANS, AND THE OCCUPATION OF THE SERBIAN BANAT, 1941-1944 Mirna Zakic, Ph.D., 2011 Directed by: Professor Jeffrey Herf, Department of History This dissertation examines the Volksdeutsche (ethnic Germans) of the Serbian Banat (northeastern Serbia) during World War II, with a focus on their collaboration with the invading Germans from the Third Reich, and their participation in the occupation of their home region. It focuses on the occupation period (April 1941-October 1944) so as to illuminate three major themes: the mutual perceptions held by ethnic and Reich Germans and how these shaped policy; the motivation behind ethnic German collaboration; and the events which drew ethnic Germans ever deeper into complicity with the Third Reich. The Banat ethnic Germans profited from a fortuitous meeting of diplomatic, military, ideological and economic reasons, which prompted the Third Reich to occupy their home region in April 1941. They played a leading role in the administration and policing of the Serbian Banat until October 1944, when the Red Army invaded the Banat. The ethnic Germans collaborated with the Nazi regime in many ways: they accepted its worldview as their own, supplied it with food, administrative services and eventually soldiers. They acted as enforcers and executors of its policies, which benefited them as perceived racial and ideological kin to Reich Germans. These policies did so at the expense of the multiethnic Banat‟s other residents, especially Jews and Serbs. In this, the Third Reich replicated general policy guidelines already implemented inside Germany and elsewhere in German-occupied Europe. -

Opening Statement Transcript.Pdf

Court 5, Case 7 15 July 47 -M1-1-ABG-Perrin (Schaefer) Official Transcript of the American Military Tribunal in the matter of the United States of America, against Wilhelm List, et al., Defendants, sitting at Nurnberg[sic], Germany, on 15 July 1947, 0930-1630, Justice Wennerstrum, presiding. THE MARSHAL: The Honorable, the Judges of Military Tribunal 5. Military Tribunal 5 is now in session. God save the United States of America and this honorable Tribunal. THE PRESIDENT: This Tribunal is convened at this time for the purpose of the presentation of the opening statements on behalf of the prosecution. Prior to the presentation of this opening statement, I wish to make a statement relative to certain motions which have been filed by the defense counsel. These motions will receive the consideration of this Tribunal following the presentation of the opening statements by the prosecution. Is the prosecution ready? GENERAL TAYLOR: Yes, Your Honor. THE PRESIDENT: You may proceed. GENERAL TAYLOR: May it please Your Honors. This is the first time, since the conclusion of the trial before the International Military Tribunal, that high-ranking officers of the Wehrmacht have appeared in this dock, charged with capital crimes committed in a strictly military capacity. The conviction and execution of Keitel and Jodl, pursuant to the judgement and sentence of the International Military Tribunal, gave rise to wide-spread public comment, not only in Germany, but also in the United States and England. Since that time, there have been several other note-worthy trials of German military leaders. In the British zone of occupation, Generals von Falkenhorst and Blumentritt have been tried for the murder of prisoners of war. -

Tegerm:.An Gen -Eral Sta~Ff: Training And3 Develiopine T Of' General .Taft

TeGerm:.an Gen-eral sta~ff: training and3 develiopine t of' general .tafTof fie rs Vol VIII , fita oi iv~c,~OM A #P.-031b Hermann FOERTSCH General der Infanterie OjO', First Army Project # 6 GERMN GONEAL S TAFF Vol VIII TRAINING AND D VLOP1 T OF GERMAN GE2IERAL STA "F OFFICER Translator: Code # 1. Editor: Dr. FREDE IKSEN Reviewer: Lt Col. VERNON HISTORICAL DIVISION EUROPEAN COMMND z Ns # P-031b INDEX CONTAINED IN~ THE GERMN COPY MS # P-031b -a- This is Volumn VIII of 30 volumes concerning the Training and Development of German Generaal Staff, Officers. It is divided into two general portions, manuscripts numbered P-031a are the re- sults of studies solicited from individual writers by the Historical Division, EUCOM, and consist of Volumes XXII to XXX inclu- sive. The evaluation and synopsis given in Volume I does not consider these vol- umes Inasmuch as this material is con- sidered to be of immediate value to the General Staff Department of the Army as well as to service schools from the level of Command and General Staff College up- ward, these volumes are submitted as they are produced rather than waiting for com- pletion of the project. Volumes I to XXI were completed for Historical D)ivision, EUCOM, by individual writers under the supervision of the Con- trol Group and consist of manuscripts numbei- ed P-031b. This particular series has been evaluated and co-ordinated by the Control Group. LOUIS M. N.AW CKY Lt Col, Armor Chief, Foreign Military Studies Branch MS # P-031b GERMAN G ERAL STAFF PROJECT LIST OF CONTRIBUT( S Vol 1* TRAINING AND DEWEN T OF GERMAN GENERAL. -

Air Power for Patton's Army

AIR POWER FOR PATTON’S ARMY The XIX Tactical Air Command in the Second World War David N. Spires Air Force History and Museums Program Washington, D. C. 2002 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Spires, David N. Air Power for Patton’s Army : the XIX Tactical Air Command in the Second World War / David N. Spires. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. 1. World War, 1939-1945—Aerial operations, American. 2. United States. Army Air Forces. Tactical Air Command, 19th—History. 3. World War, 1939- 1945—Campaigns—Western Front. 4. Close air sup- port—History—20th century. 5. United States. Army. Army, 3rd—History. I. Title. D790 .S65 2002 940.54’4973—dc21 2002000903 In Memory of Colonel John F. “Fred” Shiner, USAF (1942–1995) Foreword This insightful work by David N. Spires holds many lessons in tacti- cal air-ground operations. Despite peacetime rivalries in the drafting of service doctrine, in World War II the immense pressures of wartime drove army and air commanders to cooperate in the effective prosecution of battlefield opera- tions. In northwest Europe during the war, the combination of the U.S. Third Army commanded by Lt. Gen. George S. Patton and the XIX Tactical Air Command led by Brig. Gen. Otto P. Weyland proved to be the most effective allied air-ground team of World War II. The great success of Patton’s drive across France, ultimately crossing the Rhine, and then racing across southern Germany, owed a great deal to Weyland’s airmen of the XIX Tactical Air Command. This deft cooperation paved the way for allied victory in Westren Europe and today remains a clas- sic example of air-ground effectiveness. -

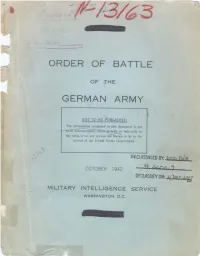

Usarmy Order of Battle GER Army Oct. 1942.Pdf

OF rTHE . , ' "... .. wti : :::. ' ;; : r ,; ,.:.. .. _ . - : , s "' ;:-:. :: :: .. , . >.. , . .,.. :K. .. ,. .. +. TABECLFCONENS TABLE OF CONTENTS Page FOREWORD iii - vi PART A - THE GERMAN HIGH COMMAND I INTRODUCTION....................... 2 II THE DEFENSE MINISTRY.................. 3 III ARMY GHQ........ 4 IV THE WAR DEPARTMENT....... 5 PART B - THE BASIC STRUCTURE I INTRODUCTION....................... 8 II THE MILITARY DISTRICT ORGANIZATION,- 8 III WAR DEPARTMENT CONTROL ............ 9 IV CONTROL OF MANPOWER . ........ 10 V CONTROL OF TRAINING.. .. ........ 11 VI SUMMARY.............. 11 VII DRAFT OF PERSON.NEL .... ..... ......... 12 VIII REPLACEMENT TRAINING UNITS: THE ORI- GINAL ALLOTMENENT.T. ...... .. 13 SUBSEQUENT DEVELOPMENTS... ........ 14 THE PRESENT ALLOTMENT..... 14 REPLACEMENT TRAINING UNITS IN OCCUPIED TERRITORY ..................... 15 XII MILITARY DISTRICTS (WEHRKREISE) . 17 XIII OCCUPIED COUNTRIES ........ 28 XIV THE THEATER OF WAR ........ "... 35 PART C - ORGANIZATIONS AND COMMANDERS I INTRODUCTION. ... ."....... 38 II ARMY GROUPS....... ....... .......... ....... 38 III ARMIES........... ................. 39 IV PANZER ARMIES .... 42 V INFANTRY CORPS.... ............. 43 VI PANZER CORPS...... "" .... .. :. .. 49 VII MOUNTAIN CORPS ... 51 VIII CORPS COMMANDS ... .......... :.. '52 IX PANZER DIVISIONS .. " . " " 55 X MOTORIZED DIVISIONS .. " 63 XI LIGHT DIVISIONS .... .............. : .. 68 XII MOUNTAIN DIVISIONS. " """ ," " """ 70 XII CAVALRY DIVISIONS.. .. ... ". ..... "s " .. 72 XIV INFANTRY DIVISIONS.. 73 XV "SICHERUNGS" -

M1035 Publication Title: Guide to Foreign Military Studies

Publication Number: M1035 Publication Title: Guide to Foreign Military Studies, 1945-54 Date Published: 1954 GUIDE TO FOREIGN MILITARY STUDIES, 1945-54 Preface This catalog and index is a guide to the manuscripts produced under the Foreign Military Studies Program of the Historical Division, United States Army, Europe, and of predecessor commands since 1945. Most of these manuscripts were prepared by former high-ranking officers of the German Armed Forces, writing under the sponsorship of their former adversaries. The program therefore represents an unusual degree of collaboration between officers of nations recently at war. The Foreign Military Studies Program actually began shortly after V-E Day, when Allied interrogators first questioned certain prominent German prisoners of war. Results were so encouraging that the program was expanded; written questions replaced oral interrogation, and later certain highly-placed German officers were asked to prepare a series of monographs. Originally the mission of the program was only to obtain information on enemy operations in the European Theater for use in the preparation of an official history of the U.S. Army in World War II. In 1946 the program was broadened to include the Mediterranean and Russian war theaters. Beginning in 1947 emphasis was placed on the preparation of operational studies for use by U.S. Army planning and training agencies and service schools. The result has been the collection of a large amount of useful information about the German Armed Forces, prepared by German military experts. While the primary aim of the program has remained unchanged, many of the more recent studies have analyzed the German experience with a view toward deriving useful lessons. -

United States Army European Command, Historical Division Typescript Studies, 1945-1954

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/tf696nb1jc No online items Register of the United States Army European Command, Historical Division Typescript Studies, 1945-1954 Hoover Institution Archives Stanford University Stanford, California 94305-6010 Phone: (650) 723-3563 Fax: (650) 725-3445 Email: [email protected] © 1999, 2012 Hoover Institution Archives. All rights reserved. 66026 1 Register of the United States Army European Command, Historical Division Typescript Studies, 1945-1954 Hoover Institution Archives Stanford University Stanford, California Contact Information Hoover Institution Archives Stanford University Stanford, California 94305-6010 Phone: (650) 723-3563 Fax: (650) 725-3445 Email: [email protected] © 1999, 2012 Hoover Institution Archives. All rights reserved. Descriptive Summary Title: United States Army European Command, Historical Division Typescript Studies, Date (inclusive): 1945-1954 Collection number: 66026 Creator: United States. Army. European Command. Historical Division Collection Size: 60 manuscript boxes(25.2 linear feet) Repository: Hoover Institution Archives Stanford, California 94305-6010 Abstract: Relates to German military operations in Europe, on the Eastern Front, and in the Mediterranean Theater, during World War II. Studies prepared by former high-ranking German Army officers for the Foreign Military Studies Program of the Historical Division, U.S. Army, Europe. Language: English. Access Collection open for research. The Hoover Institution Archives only allows access to copies of audiovisual items. To listen to sound recordings or to view videos or films during your visit, please contact the Archives at least two working days before your arrival. We will then advise you of the accessibility of the material you wish to see or hear. Please note that not all audiovisual material is immediately accessible. -

HIGHER HEADQUARTERS and MECHANIZED GHQ UNITS (4 July 1943) the GERMAN WORLD WAR II ORGANIZATIONAL SERIES

GERMAN WORLD WAR II ORGANIZATIONAL SERIES Volume 5/II HIGHER HEADQUARTERS AND MECHANIZED GHQ UNITS (4 July 1943) THE GERMAN WORLD WAR II ORGANIZATIONAL SERIES 1/I 01.09.39 Mechanized Army Formations and Waffen-SS Formations (3rd Revised Edition) 1/II-1 01.09.39 1st and 2nd Welle Army Infantry Divisions 1/II-2 01.09.39 3rd and 4th Welle Army Infantry Divisions 1/III 01.09.39 Higher Headquarters — Mechanized GHQ Units — Static Units (2nd Revised Edition) 2/I 10.05.40 Mechanized Army Formations and Waffen-SS Formations (2nd Revised Edition) 2/II 10.05.40 Higher Headquarters and Mechanized GHQ Units (2nd Revised Edition) 3/I 22.06.41 Mechanized Army Divisions - (2nd Revised Edition) 3/II 22.06.41 Higher Headquarters and Mechanized GHQ Units (2nd Revised Edition) 3/III 22.06.41 Waffen-SS Mechanized Formations and GHQ Service Units 4/I 28.06.42 Mechanized Army Divisions - (2nd Revised Edition) 4/II 28.06.42 Mechanized GHQ Units and Waffen-SS Formations 5/I 04.07.43 Mechanized Army Formations 5/II 04.07.43 Higher Headquarters and Mechanized GHQ Units 5/III 04.07.43 Waffen-SS Higher Headquarters and Mechanized Formations IN PREPARATION FOR PUBLICATION 2008/2009 3/V 22.06.41 Army Security, Occupation, and Provost Marshal Forces 7/I 06.06.44 Mechanized Army Formations IN PREPARATION FOR PUBLICATION 01.09.39 Landwehr Division — Mountain Divisions — Cavalry Brigade 10.05.40 Army Divisions GHQ Service ggUnits Static Units 22.06.41 Army Divisions Static Units 28.06.42 Higher Headquarters Army Divisions Static Units 04.07.43 Army Divisions Static Units -

Foreign Military Studies 1945-54 Catalog & Index

HISTORICAL DIVISION GUIDE TO_FOREIGN MILITARY STUDIES 1945-54_CATALOG & INDEX HEADQUARTERS_UNITED STATES ARMY, EUROPE_1954 AVAILABILITY OF STUDIESCopie Unless otherwise indicated, the studies listed in this guide are Library, Ft. Leslie J. McNair,s Washington 25, D.C.; Armed Forces unclassified. Their release to nonofficial and to non-U.S. Staff College Library, Fortress Monroe, Va.; Army War College agencies and individuals, however, is controlled. Agencies and Library, Carlisle Barracks, Pa.; and Command and General Staff nationals of foreign countries desiring access to the collection College Library, Fort Leavenworth, Kansas. should apply for per mission through normal liaison channels. The channels and procedures for loans are as follows: Ninety percent of the studies listed exist only as typed a. U.S. Army, Navy, and Air Force Units in the manuscripts. Where multiple copies of studies have been made, areas not specified below. Requests should be forwarded through either through printing or other wise, this fact is noted in the channels to the Office of the Chief of Military History, Department individual catalog entries. Copies of such studies usually can be of the Army, Washington 25, D.C. Historical channels are obtained on loan by official U. S. agencies. Where only single authorized. file copies exist, these must usually be researched in the b. U.S. Army, Navy, and Air Force Units in USAREUR, USAFE, repository itself. TRUST; Re quests should be forwarded through channels to All reproduced studies may be ob tained on loan for varying Historical Division, Hq. USAREUR, APO 164, U.S. Army periods. They are also available for limited issue on a while-they- Historical channels are authorized. -

Hostage Case090901mit Deckblatt

Hostage Case US Military Tribunal, Nuremberg, Judgment of 19 February 1948 Page numbers in braces refer to US Military Tribunal Nuremberg, judgment of 19 February 1948, in Trials of War Criminals Before the Nuremberg Military Tribunals Under Control Council Law No. 10, Volume XI/2 {1230} XI. JUDGMENT A. Opinion and Judgment of Military Tribunal V In the matter of the United States of America against Wilhelm List, et al., sitting at Nuernberg, Germany, on 19 February 1948, Justice Wennerstrum, presiding. Presiding JUDGE WENNERSTRUM: Judge Carter will read the first portion of the opinion. JUDGE CARTER: In this case, the United States of America prosecutes each of the defendants on one or more of four counts of an indictment charging that each and all of said defendants unlawfully, willfully, and knowingly committed war crimes and crimes against humanity as such crimes are denned in Article 11 of the Control Council Law No. 10. They are charged with being principals in and accessories to the murder of thousands of persons from the civilian population of Greece, Yugoslavia, Norway, and Albania between September 1939 and May 1945 by the use of troops of the German armed forces under the command of and acting pursuant to orders issued, distributed, and executed by the defendants at the bar. It is further charged that these defendants participated in a deliberate scheme of terrorism and intimidation, wholly unwarranted and unjustified by military necessity, by the murder, ill-treatment and deportation to slave labor of prisoners of war and members of the civilian populations in territories occupied by the German armed forces; by plundering and pillaging public and private property and wantonly destroying cities, towns, and villages for which there was no military necessity. -

The Muernberg War Crimes Trials Under Control Goungil Law No

ON THE MUERNBERG WAR CRIMES TRIALS UNDER CONTROL GOUNGIL LAW NO. 10 by TELFORD TAYLOR Brigadier General, U. S. A. Chief of Counsel for War Crimes Washington, D. C.JAG SCHOOL 15 August 1949 MAR 2 0 1997 LIBRARY For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U. 8. Government Printing Oflee Washington 25, D. C. - Price 70 cents fioc LETTER OF TRANSMI~AL------,------------------------------------ v INTR~D~~ION-----------------------------------------------------VII HISTORICALBACKGROUND.......................................... 1 J. C. S. 1023/10............................................... 4 Control Council Law No. 10.................................... 6 Executive Order No. 9679-------------------------------------- 10 THE "SUBSEQUENTPROCEEDINGS DIVISION" OF OCCPAC------------- 13 Staff Recruitment and Organization .............................. 14 Operations---------------------------------------------------- 15 A SECONDTRIAL UNDERTHE LONDONCHARTER?.................... 22 MILITARYGOVERNMENTORDINANCE NO. 7.......................... 28 THE MILITARYTRIBUNALS, THE SECRETARYGENERAL, AND THE OFFICE, CHIEFOF COUNSELFOR WAR CRIMES.............................. The Military Tribunals The Central Secretariat- - -------_--------------------y---------- The Office, Chief of Counsel for War Crimes ....................... Foreign Delegations --------- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - ---- - - - - - - - ---- - Defense Counsel----------------------------------------------- WAR CRIMESSUSPECTS AND WITNESSES............................. Incarceration------------------------------------------------- -

Generale Der Wehrmacht Copyright by Deutsches Wehrkundearchiv

A 3559 - Generale der Wehrmacht Dietrich von Saucken-A3559-001.jpg Eberhard Kinzel-A3559-002.jpg Eberhard Thunert-A3559-003.jpg Eberhard von Kurowski-A3559-004.jpg Eberhard von Mackensen-A3559-005.jpg Eberhardt Rodt-A3559-006.jpg Eccard Freiherr von Gablenz-A3559-007.jpgEdgar Feuchtinger-A3559-008.jpg Edmund Blaurock-A3559-009.jpg Edmund Hoffmeister-A3559-010.jpg Eduard Crasemann-A3559-011.jpg Eduard Dietl-A3559-012.jpg Eduard Hauser-A3559-013.jpg Eduard Metz-A3559-014.jpg Eduard Wagner-A3559-015.jpg Egbert Picker-A3559-016.jpg Copyright by Deutsches Wehrkundearchiv - 1 - A 3559 - Generale der Wehrmacht Egon von Neindorff-A3559-017.jpg Ehrenfried-Oskar Boege-A3559-018.jpg Emil Vogel-A3559-019.jpg Erhard Berner-A3559-020.jpg Erhard Milch-A3559-021.jpg Erhard Raus-A3559-022.jpg Erich Abraham-A3559-023.jpg Erich Barenfanger-A3559-024.jpg Erich Bey-A3559-025.jpg Erich Brandenberger-A3559-026.jpg Erich Buschenhagen-A3559-027.jpg Erich Fellgiebel-A3559-028.jpg Erich Freiherr von Seckendorff-A3559-029.jpgErich Friderici-A3559-030.jpg Erich Hoepner-A3559-031.jpg Erich Jaschke-A3559-032.jpg Copyright by Deutsches Wehrkundearchiv - 2 - A 3559 - Generale der Wehrmacht Erich Kahsnitz-A3559-033.jpg Erich Marcks-A3559-034.jpg Erich Raeder-A3559-035.jpg Erich Reuter-A3559-036.jpg Erich Schopper-A3559-037.jpg Erich Straube-A3559-038.jpg Erich v. Manstein-A3559-039.jpg Erich von Manstein, Brandenberger-A3559-040.jpg Erich von Manstein-A3559-041.jpg Erik Hansen-A3559-042.jpg Ernst Bolbrinker-A3559-043.jpg Ernst Dehner-A3559-044.jpg Ernst Felix Fackenstedt-A3559-045.jpg Ernst Haccius-A3559-046.jpg Ernst Hammer-A3559-047.jpg Ernst Maisel-A3559-048.jpg Copyright by Deutsches Wehrkundearchiv - 3 - A 3559 - Generale der Wehrmacht Ernst Rupp-A3559-049.jpg Ernst Seifert-A3559-050.jpg Ernst Udet-A3559-051.jpg Ernst v.