By Norman Dannatt

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Sheffield Hallam University Thesis

How do I look? Viewing, embodiment, performance, showgirls, and art practice. CARR, Alison J. Available from the Sheffield Hallam University Research Archive (SHURA) at: http://shura.shu.ac.uk/19426/ A Sheffield Hallam University thesis This thesis is protected by copyright which belongs to the author. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. Please visit http://shura.shu.ac.uk/19426/ and http://shura.shu.ac.uk/information.html for further details about copyright and re-use permissions. How Do I Look? Viewing, Embodiment, Performance, Showgirls, & Art Practice Alison Jane Carr A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of Sheffield Hallam University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy ProQuest Number: 10694307 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10694307 Published by ProQuest LLC(2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 Declaration I, Alison J Carr, declare that the enclosed submission for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, and consisting of a written thesis and a DVD booklet, meets the regulations stated in the handbook for the mode of submission selected and approved by the Research Degrees Sub-Committee of Sheffield Hallam University. -

Wehrmacht Uniforms

Wehrmacht uniforms This article discusses the uniforms of the World uniforms, not included here, began to break away in 1935 War II Wehrmacht (Army, Air Force, and with minor design differences. Navy). For the Schutzstaffel, see Uniforms and Terms such as M40 and M43 were never designated by the insignia of the Schutzstaffel. Wehrmacht, but are names given to the different versions of the Modell 1936 field tunic by modern collectors, to discern between variations, as the M36 was steadily sim- plified and tweaked due to production time problems and combat experience. The corresponding German term for tunic is Feldbluse and literally translates “field blouse”. 1 Heer 1.1 Insignia Main article: Ranks and insignia of the Heer (1935– 1945) For medals see List of military decorations of the Third Reich Uniforms of the Heer as the ground forces of the Wehrmacht were distinguished from other branches by two devices: the army form of the Wehrmachtsadler or German general Alfred Jodl wearing black leather trenchcoat Hoheitszeichen (national emblem) worn above the right breast pocket, and – with certain exceptions – collar tabs bearing a pair of Litzen (Doppellitze “double braid”), a device inherited from the old Prussian Guard which re- sembled a Roman numeral II on its side. Both eagle and Litzen were machine-embroidered or woven in white or grey (hand-embroidered in silk, silver or aluminium for officers). Rank was worn on shoulder-straps except for junior enlisted (Mannschaften), who wore plain shoulder- straps and their rank insignia, if any, on the left upper sleeve. NCO’s wore a 9mm silver or grey braid around the collar edge. -

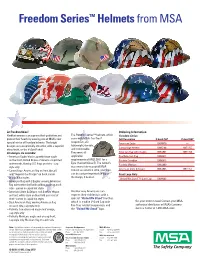

Freedom Series™ Helmetsfrom

Freedom Series™ Helmets from MSA Let Freedom Shine! Ordering Information Hardhat wearers can express their patriotism and The Freedom Series™ helmets, which Freedom Series ® protect their heads by wearing one of MSA’s new come with MSA’s Fas-Trac Full Decoration V-Gard CAP V-Gard HAT suspension, are special series of Freedom helmets. The bright American Eagle 10079479 — designs are exceptionally attractive, with a superior lightweight, durable, Camouflage Helmet 10065166 10071155 shiny finish, on the V-Gard® shell. and comfortable. Six designs are available: They meet all American Flag with 2 Eagles 10052947 10071159 • American Eagle: black cap with large eagle applicable Dual American Flag 10050611 — on the front, United States of America imprinted requirements of ANSI Z89.1 for a Patriotic Canadian 10050613 — Type I helmet (Class E). The helmet’s underneath, flowing U.S. flags on sides - cap Patriotic Mexican 10052600 — style only accessory slots accept all MSA American Stars & Stripes 10052945 10071157 • Camouflage: American flag on front (decal) V-Gard accessories. Also, your logo and “Support Our Troops” on back comes can be custom-imprinted on top of Front Logo Only the design, if desired. in cap & hat styles “United We Stand” V-Gard Cap 10034263 — • American Flag with 2 Eagles: waving American flag over entire shell with golden eagle on each side - comes in cap & hat styles • American Stars & Stripes: red & white stripes Another way Americans can on front, white stars on blue field over rest of express their solidarity is with a shell -comes in cap & hat styles special “United We Stand” hardhat, • Dual American Flag: waving American flag which is a white V-Gard Cap with Get your order in now! Contact your MSA- on each side, cap style only Fas-Trac ratchet suspension, and authorized distributor, or MSA’s Customer • Patriotic Canadian: red maple leaf design, the “United We Stand” logo. -

Army Dress Regulations (All Ranks)

ARMY DRESS REGULATIONS (ALL RANKS) Part 4 – GENERAL STAFF DRESS REGULATIONS Ministry of Defence PS12(A) February 2017 GENERAL ORDER HORSE GUARDS 1st April, 1846 The Queen having been pleased to approve of the dress of the Officers of the Army being established according to the following descriptions, the Commander-in-Chief has received Her Majesty’s commands to enjoin the strictest attention thereto; and His Grace accordingly holds all General Officers, Colonels of Regiments, and Commanding Officers of Corps, responsible that these Orders for regulating the Dress shall be scrupulously obeyed. The Commander-in-Chief has received Her Majesty’s special commands to declare, that any Colonel or Commanding Officer who shall take upon himself to introduce or sanction the addition of an ornament, lace, or embroidery, or to sanction a deviation from the approved Patterns in any respect whatsoever, without due authority being previously obtained for that purpose, will incur Her Majesty’s displeasure. By Command of Field Marshall The Duke of Wellington, K.G., Commander-in-Chief Part 4 13 Apr 16 04.01. Scope. Part 4 of these Regulations deals with Corps and Regimental Dress Regulations. These sections cover Dress Regulations for the General Staff. 04.02. Contents. Contents are as follows: a. Section 1 – Introduction b. Section 2 – Field Marshal’s Dress c. Section 3 – General Officer’s Dress d. Section 4 – Brigadier and Colonels’ Dress e. Section 5 – Honorary and E1 Appointments and Retired Officers Dress f. Section 6 – Joint Service Dress Tables g. Section 7 – Guide to the Correct Order of Dress 04.03. -

Their Stories

NORTH YORKSHIRE’S UNSUNG HEROES THEIR STORIES Acknowledgements We are indebted to the men and women who have given their time to share their valuable stories and kindly allowed us to take copies of their personal photographs. We are also extremely grateful to them for allowing their personal histories to be recorded for the benefit of current and future generations. In addition, we would like to thank Dr Tracy Craggs, who travelled the length and breadth of North Yorkshire to meet with each of the men and women featured in this book to record their stories. We would also like to thank her – on behalf of the Unsung Heroes – for her time, enthusiasm and kindness. © Copyright Community First Yorkshire, 2020 All rights reserved. The people who have shared their stories for this publication have done so with the understanding that they will not be reproduced without prior permission of the publisher. Any unauthorised copying or reproduction will constitute an infringement of copyright. Contents Foreword 3 Introduction 4 Their stories 5 – 45 Glossary 46 NORTH YORKSHIRE’S UNSUNG HEROES I THEIR STORIES Foreword North Yorkshire has a strong military history and a continuing armed forces presence. The armed forces are very much part of our local lives – whether it’s members of our own families, the armed forces’ friends in our children’s schools, the military vehicles on the A1, or the jets above our homes. The serving armed forces are visible in our county – but the older veterans, our unsung heroes, are not necessarily so obvious. With the Ex-Forces Support North Yorkshire project we wanted to raise the profile of older veterans across North Yorkshire. -

Commonwealth

COMMONWEALTH COMMONWEALTH Michael Hardt Antonio Negri THE BELKNAP PRESS OF HARVARD UNIVERSITY PRESS Cambridge, Massachusetts 2009 Copyright © 2009 by Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Hardt, Michael, 1960– Commonwealth / Michael Hardt, Antonio Negri. p. cm. Sequel to “Empire” and “Multitude.” Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-674-03511-9 (cloth : alk. paper) 1. International or ga ni za tion. 2. International cooperation. 3. Globalization. I. Negri, Antonio, 1933– II. Title. JZ1318.H368 2009 321.02—dc22 2009012652 CONTENTS Preface: The Becoming-Prince of the Multitude vii PART 1 Republic (and the Multitude of the Poor) 1.1 Republic of Property 3 1.2 Productive Bodies 22 1.3 The Multitude of the Poor 39 De Corpore 1: Biopolitics as Event 56 PART 2 Modernity (and the Landscapes of Altermodernity) 2.1 Antimodernity as Resistance 67 2.2 Ambivalences of Modernity 83 2.3 Altermodernity 101 De Homine 1: Biopolitical Reason 119 PART 3 Capital (and the Struggles over Common Wealth) 3.1 Metamorphoses of the Composition of Capital 131 3.2 Class Struggle from Crisis to Exodus 150 3.3 Kairos of the Multitude 165 De Singularitate 1: Of Love Possessed 179 INTERMEZZO: A FORCE TO COMBAT EVIL 189 vi CONTENTS PART 4 Empire Returns 4.1 Brief History of a Failed Coup d’État 203 4.2 After U.S. Hegemony 219 4.3 Genealogy of Rebellion 234 De Corpore 2: Metropolis 249 PART 5 Beyond Capital? 5.1 Terms of the Economic Transition 263 5.2 What Remains of Capitalism 280 5.3 Pre-shocks along the Fault Lines 296 De Homine 2: Cross the Threshold! 312 PART 6 Revolution 6.1 Revolutionary Parallelism 325 6.2 Insurrectional Intersections 345 6.3 Governing the Revolution 361 De Singularitate 2: Instituting Happiness 376 Notes 387 Acknowledgments 427 Index 428 PR EFA C E : T H E B ECO M ING- PR I N C E OF THE MULTITUDE People only ever have the degree of freedom that their audacity wins from fear. -

Hornet Heads Page 1.Ai

HORNET 1/35th Scale Resin Head Sets Bare Heads HH/1 5 bare different heads HH/11 5 different heads laughing, joking HH/2 5 different character heads HH/12 5 different bareheads, neutral expression HH/3 5 heads, close cropped hair HH/13 5 different youthful heads WW2 hair HH/4 5 different heads, WW2 haircuts HH/14 5 different heads, snarling, gasping HH/5 5 different African bald heads HH/15 5 heads, smoking (add own ciggies) HH/6 5 different European bald heads HH/16 5 more European bald heads HH/7 5 different east Asian bald heads HH/17 5 different heads eating, drinking HH/8 5 different middle aged euro heads HH/18 5 different heads, necks turned right or left HH/9 5 different heads, sleeping HH/19 5 different heads, looking up or stretched out HH/10 5 different female heads - no hair! HH/20 5 different heads looking down Page 1 HORNET 1/35th Scale Resin Head Sets Bare Heads / US Heads HH/21 5 different heads, gaunt or battleweary HH/31 Heads, 2 old men, 2 youths, 1 boy HH/22 5 more heads with WW2 style haircuts HH/32 5 bare with emaciated features HH/23 5 bandaged heads HH/33 Bare heads with Ultra short haircuts HH/24 5 more heads with european faces HH/34 5 Heads with Aquiline features HH/25 5 more european heads HH/35 5 More bare heads with Caucasian features HH/26 5 bald heads with defeated expressions HCH/1 Rural Civilians WWII Set 1 HH/27 5 bald heads with triumphant, exulting faces HCH/2 Rural Civilians WWII Set 2 HH/28 5 headset, bare heads with hooked ('semitic') noses HUH/6 5 heads with USMC early type M1/cover HH/29 5 Bareheads with one eye closed. -

1939-45 – Unit Manual. the “Home Front” Unit Within the WW2

New Zealand Home Front – 1939-45 – Unit Manual. The “Home Front” Unit within the WW2 Historical Re-enactment Society will present to the public a snapshot of “things at home” during WW2 – and in particular the Emergency services during the period 1941 through to 1945. The period directly after the Japanese attack on the American naval base at Pearl Harbour. This then lead the NZ Government to look at home defence in case of invasion. Potentially – The Home Front Unit could cover representation from Home Guard to Nursing and Ambulance to the Fire Service, Emergency Protection Services to the Coast Watch. We currently have Club members who will wear Home Guard “uniform” – this will either be prior to the issue of Uniforms when they wore their own clothes with the addition of a HG armband so as to be clearly identified as “official” and not some form of enemy agent or spy or once Uniforms were issued. Home Guard members carried a variety of their own weapons until the Army had surplus and could supply them with both weapons and uniforms. Original Home Guard prior to uniform issue. Other members of the Home Guard will be in Battledress Uniforms as worn by their brothers in arms based overseas with the 2NZEF. An example of WW2 Battledress and webbing, helmet, cap and boots as wore by HG. Uniformed Home Guard 1941-1945: • Regulation issue WW2 Battledress with Home Guard Shoulder titles (black background with white writing) – (no service stripes or brigade flashings- rank worn if applicable) • 37 Pattern webbing – including puttees and belt • Black lace-up boots. -

75 Ft Diameter Bin

75 Ft Diameter Bin Models: 40–SERIES BIN Construction Manual PNEG-4075 Version 1.0 Date: 05-27-13 PNEG-4075 All information, illustrations, photos, and specifications in this manual are based on the latest information available at the time of publication. The right is reserved to make changes at any time without notice. 2 Pneg-4075 75 Ft Diameter 40-Series Bin Table of Contents Contents Chapter 1 Safety Precautions ....................................................................................................................7 Safety Guidelines ........................................................................................................................7 Cautionary Symbols ....................................................................................................................9 Safety Decals............................................................................................................................10 Safety Sign-off Sheet.................................................................................................................13 Chapter 2 General Overview ....................................................................................................................15 General Information...................................................................................................................15 Anchor Bolt Charts ....................................................................................................................15 Tools Required for Construction..................................................................................................17 -

Military and Civilian Figures Made by Enthusiasts for Enthusiasts

ASSET Military and Civilian Figures made by Enthusiasts for Enthusiasts. 12, Norwood Drive, North Harrow, Middx HA2 7PE 020-8868-0422 This list supersedes previous lists © ASSET December 2010/11 www.assetminiatures.co.uk [email protected] LAST YEAR’S PRICES HELD 1 POLICE FIGURES ALL FIGURES STANDING UNLESS OTHERWISE STATED NUMBER DESCRIPTION PRICE CODE P1 W.P.C., may be painted as several different British Forces A P1a As P1 Wearing Reflective Jacket A P2 Military Policeman, No. 2 Dress - may be painted as R.A.F. A P3 British P.C. - Dog Handler - standing dog B P4 British P.C. - Dog Handler - sitting dog B P5 British P.C. wearing Home Office Pattern helmet A P6 British P.C. wearing Cap - white top A P6a As P6, Blue cap A P6b As P6, Reflective Jacket, Cap - White top A P7 City of London P.C., hands behind back A P8 As P7, Painted as Sergeant A P9 P.C. - Point Duty wearing Helmet A P10 ―T.J‖ P.C. crouching - comforting little boy, can be supplied with either flat cap, H.O. helmet or City of London Helmet. C P11 P.C. wearing crested helmet - ―Star‖ Badge A P12 Met. Police Dog Handler - 1960‘s - sitting dog B P13 City of London P.C. - Point duty A P14 City of London - Mounted Branch. May be painted as Met. J P14a Mounted P.C. wearing reflective jacket, Painted as Met. Or City J P15 W.P.C in trousers A P15a As P15 Wearing Reflective Jacket A P16a Royal Military Police - mounted - carrying lance D P16b Royal Military Police - mounted - carrying sabre D P17 Hampshire Constabulary P.C., hands behind back A P18 Merseyside Police Sergeant - with signalling stick A P19 R.A.F Police Dog Handler and Air Dog (Display Team) B P20 W.P.C walking A P20a As P20 wearing Reflective Jacket A P21 P.C. -

The Lincoln Center Repertory Theatre, 1958-1965

This dissertation has been microiilmed exactly as received 67-2524 ROBERTS, Kenneth Harris, 1930- THE LINCOLN CENTER REPERTORY THEATRE, 1958-1965. The Ohio State University, Ph.D„ 1966 Speech-Theater University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan THE nCNCOm CENTER REPERTORÏ THEATRE, 1958-1965 DISSEREATION Presented in Paarbial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Kenneth H a rris R o b erts, B .A ., M.A. ******* The Ohio State University 1966 Approved by A dviser Department of ^eech VITA. November l 6, 1930 Bom - Bedford., Virginia 1957 .. B.A., Denison University, Granville, Ohio 1957-1958 Instructor, Department of Speech Denison University, Granville, Ohio 1958 . M.A., The Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio 1958-1961 Assistant Professor and Director of Theatre Kansas State College, Pittsburg, Kansas 1961-1963 Graduate A ssistant, Department of Speech The Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio 1963-1964 Professional Actoi*, New York, New York 1964-1966 lecturer. Department of Speech and Theatre Hunter College, New York, New York PIEEBS OF STUDY Major Field: Theatre Studies in History of Theatre, Professor John McDowell Studies in Dramatic Literature, Professor Charles C. B itter Studies in Directing and Classical Criticism, Professor Boy H. Bowen Studies in Educational Theatre: Theoiy and Production, P ro fe sso r W alter 8 . Dewey Minor Fields: Badio-Television and Motion Picture Photography Studies in Badio and Television, Professor James E. lynch Studies in Motion Picture Photography, Professor Bobert W. Wagner ii CONTENTS VITA ................................................................................................................................ i i Chapter Page I . THE ORIGIN AND DEVELOÏMENT OF THE LINCOLN CENTER COMPLEX, 1 Five Developments That Made Lincoln Center Possible The Beginning The Constituents of Lincoln Center Acquiring the Laud and Relocation of Tenants Raising the Funds The Presidents of Lincoln Center Early Criticism of the Center I I . -

HANDSCHARSTRIKE This Range of Figures Enables You to Recreate The

HANDSCHARSTRIKE WAFFEN-SS GRENADIERS This range of figures enables you to recreate the struggle for These Waffen SS figures depict the WWII grenadier in mix Muslim independence in WWII Bosnia, against the communist smock and M43 jacket partisans and nationalist Cetniks on the wargaming battlefield. BBG1 Officer advancing with MP40, The 13 th Waffen SS Division “Handschar” was raised in the Officer crouching with MP40 £3.00 spring of 1943 from Muslim and Croatian volunteers as part of NCO advancing with MP40 and panzerfaust, an ambitious plan to create a Muslim state in the Balkans NCO crouching with grenade and MP40 under the control of the SS. Trained to the highest standards in France and Germany (to escape Croatian interference) the Infantry jager advancing with panzerfaust men of the Handschar entered the terrible battlefield of Bosnia Infantryman advancing with K98 BBG2 £2.25 early in 1944. Wearing the traditional fez and observing Infantryman advancing with K98 and traditional Muslim religious customs, they gained a fearsome demolition charge reputation in combat, giving and expecting no quarter as they cleared Bosnia of their traditional enemies. Panzerjager advancing with 38Kg magnetic mine £2.25 As the tide of war turned on the axis occupiers in the Balkans BBG3 Sniper prone firing K98 the men on the Handschar found themselves fighting a bitter Sniper advancing with K98 war outside their security zone. This led to some desertions by some elements fearing for the security of their families, many Infantryman kneeling firing GWR43 Muslim volunteers were released from service and continued a Infantryman advancing with GWR43 and guerrilla war in Bosnia in a vain hope of keeping the idea of a £2.25 BBG4 panzerfaust Muslim state alive.