Commonwealth

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Sheffield Hallam University Thesis

How do I look? Viewing, embodiment, performance, showgirls, and art practice. CARR, Alison J. Available from the Sheffield Hallam University Research Archive (SHURA) at: http://shura.shu.ac.uk/19426/ A Sheffield Hallam University thesis This thesis is protected by copyright which belongs to the author. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. Please visit http://shura.shu.ac.uk/19426/ and http://shura.shu.ac.uk/information.html for further details about copyright and re-use permissions. How Do I Look? Viewing, Embodiment, Performance, Showgirls, & Art Practice Alison Jane Carr A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of Sheffield Hallam University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy ProQuest Number: 10694307 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10694307 Published by ProQuest LLC(2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 Declaration I, Alison J Carr, declare that the enclosed submission for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, and consisting of a written thesis and a DVD booklet, meets the regulations stated in the handbook for the mode of submission selected and approved by the Research Degrees Sub-Committee of Sheffield Hallam University. -

Change the World Without Taking Power. the Meaning of Revolution Today

Change the World without Taking Power. The Meaning of Revolution Today. John Holloway Originally published 2002 by Pluto Press Chapter 1 – The Scream . 2 Chapter 2 – Beyond the State? . 9 Chapter 3 – Beyond Power? . 14 Chapter 4 – Fetishism . 30 Chapter 5 – Fetishism and Fetishisation . 52 Chapter 6 – Anti-fetishism and Criticism . 70 Chapter 7 – The Tradition of Scientific Marxism . 77 Chapter 8 – The Critical-Revolutionary Subject . 91 Chapter 9 – The Material Reality of Anti-Power . .101 Chapter 10 – The Material Reality of Anti-Power and the Crisis of Capital . Chapter 11 – Revolution? . 132 1 Chapter 1 - The Scream I In the beginning is the scream. We scream. When we write or when we read, it is easy to forget that the beginning is not the word, but the scream. Faced with the mutilation of human lives by capitalism, a scream of sadness, a scream of horror, a scream of anger, a scream of refusal: NO. The starting point of theoretical reflection is opposition, negativity, struggle. It is from rage that thought is born, not from the pose of reason, not from the reasoned-sitting-back-and-reflecting-on- the-mysteries-of-existence that is the conventional image of ‘the thinker’. We start from negation, from dissonance. The dissonance can take many shapes. An inarticulate mumble of discontent, tears of frustration, a scream of rage, a confident roar. An unease, a confusion, a longing, a critical vibration. Our dissonance comes from our experience, but that experience varies. Sometimes it is the direct experience of exploitation in the factory, or of oppression in the home, of stress in the office, of hunger and poverty, or of state violence or discrimination. -

Wehrmacht Uniforms

Wehrmacht uniforms This article discusses the uniforms of the World uniforms, not included here, began to break away in 1935 War II Wehrmacht (Army, Air Force, and with minor design differences. Navy). For the Schutzstaffel, see Uniforms and Terms such as M40 and M43 were never designated by the insignia of the Schutzstaffel. Wehrmacht, but are names given to the different versions of the Modell 1936 field tunic by modern collectors, to discern between variations, as the M36 was steadily sim- plified and tweaked due to production time problems and combat experience. The corresponding German term for tunic is Feldbluse and literally translates “field blouse”. 1 Heer 1.1 Insignia Main article: Ranks and insignia of the Heer (1935– 1945) For medals see List of military decorations of the Third Reich Uniforms of the Heer as the ground forces of the Wehrmacht were distinguished from other branches by two devices: the army form of the Wehrmachtsadler or German general Alfred Jodl wearing black leather trenchcoat Hoheitszeichen (national emblem) worn above the right breast pocket, and – with certain exceptions – collar tabs bearing a pair of Litzen (Doppellitze “double braid”), a device inherited from the old Prussian Guard which re- sembled a Roman numeral II on its side. Both eagle and Litzen were machine-embroidered or woven in white or grey (hand-embroidered in silk, silver or aluminium for officers). Rank was worn on shoulder-straps except for junior enlisted (Mannschaften), who wore plain shoulder- straps and their rank insignia, if any, on the left upper sleeve. NCO’s wore a 9mm silver or grey braid around the collar edge. -

Eugen Ehrlich, Evgeny Pashukanis, and Meaningful Freedom Through Incremental Jurisprudential Change

Journal of Libertarian Studies JLS Volume 23 (2019): 64–90 A Practical Approach to Legal- Pluralist Anarchism: Eugen Ehrlich, Evgeny Pashukanis, and Meaningful Freedom through Incremental Jurisprudential Change Jason M. Morgan2 ABSTRACT: John Hasnas (2008) has famously argued that anarchy is obvious and everywhere. It is less well known, however, that Hasnas also argues that anarchy must be achieved gradually. But how can this work? In this paper, I show that directly confronting state power will never produce viable anarchy (or minarchy). Using the example of Soviet jurist Evgeny Pashukanis, I detail an episode in apparent anti-statism which, by relying on the state, ended in disaster for the putative anti-statist. I next show how combining the theories of Austrian legal thinker Eugen Ehrlich and American political philosopher William Sewell, Jr., can lead to a gradual undoing of state power via case law. Finally, I bring in the example of Japanese jurist and early anti-statist Suehiro Izutarō as a warning. Suehiro also attempted to decrease state power by means of case law, but because he lacked a clear anti-statist teleology he ended up becoming an accomplice of state power, even imperialism. The way to Hasnian anarchy/minarchy lies through the skillful application of case law with an eye always towards the attenuation, and eventual elimination, of the power of the state. Jason M. Morgan ([email protected]) is associate professor of foreign languages at Reitaku University. The author would like to thank Lenore Ealy, Joe Salerno, and Mark Thornton for helpful comments on an early draft of this article. -

Marxist and Soviet Law Stephen C

Saint Louis University School of Law Scholarship Commons All Faculty Scholarship 2014 Marxist and Soviet Law Stephen C. Thaman Saint Louis University School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.slu.edu/faculty Part of the Comparative and Foreign Law Commons, Criminal Law Commons, Criminal Procedure Commons, and the European Law Commons Recommended Citation Thaman, Stephen C., Marxist and Soviet Law (2014). The Oxford Handbook of Criminal Law (Markus D. Dubber and Tatjana Hörnle, eds.), Chpt. 14, 2014. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of Scholarship Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. No. 2015-2 Marxist and Soviet Law The Oxford Handbook of Criminal Law Stephen C. Thaman Electronic copy available at: http://ssrn.com/abstract=2570530 The Oxford Handbook of CRIMINAL LAW Edited by MARKUS D. DUBBER and TATJANA HÖRNLE 1 9780199673599_Hornle_Book.indb 3 Electronic copy available at: http://ssrn.com/abstract=257053010/28/2014 1:05:38 PM 1 Great Clarendon Street, Oxford, ox2 6dp, United Kingdom Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries © The several contributors 2014 The moral rights of the authors have been asserted First Edition published in 2014 Impression: 1 All rights reserved. -

Copyright © and Moral Rights for This Phd Thesis Are Retained by the Author And/Or Other Copyright Owners. a Copy Can Be Downlo

Taylor, Owen (2014) International law and revolution. PhD Thesis. SOAS, University of London. http://eprints.soas.ac.uk/id/eprint/20343 Copyright © and Moral Rights for this PhD Thesis are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners. A copy can be downloaded for personal non‐commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This PhD Thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder/s. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. When referring to this PhD Thesis, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the PhD Thesis must be given e.g. AUTHOR (year of submission) "Full PhD Thesis title", name of the School or Department, PhD PhD Thesis, pagination. INTERNATIONAL LAW AND REVOLUTION OWEN TAYLOR Thesis submitted for the degree of PhD 2014 Law Department SOAS, University of London 1 Declaration for SOAS PhD thesis I have read and understood regulation 17.9 of the Regulations for students of the SOAS, University of London concerning plagiarism. I undertake that all the material presented for examination is my own work and has not been written for me, in whole or in part, by any other person. I also undertake that any quotation or paraphrase from the published or unpublished work of another person has been duly acknowledged in the work which I present for examination. Signed: ____________________________ Date: _________________23/10/2014 2 ABSTRACT: This thesis aims to provide an investigation into how revolutionary transformation aimed to affect the international legal order itself, rather than what the international order might have to say about a revolution. -

The Situation on the International Legal Theory Front: the Power of Rules and the Rule of Power

q EJIL 2000 ............................................................................................. The Situation on the International Legal Theory Front: The Power of Rules and the Rule of Power Gerry Simpson* Abstract The rejuvenation of international law in the last decade has its source in two developments. On the one hand, ‘critical legal scholarship’ has infiltrated the discipline and provided it with a new sensibility and self-consciousness. On the other hand, liberal international lawyers have reached out to International Relations scholarship to recast the ways in which rules and power are approached. Meanwhile, the traditional debates about the source and power of norms have been invigorated by these projects. This review article considers these developments in the light of a recent contribution to international legal theory, Michael Byers’ Custom, Power and the Power of Rules. The article begins by entering a number of reservations to Byers’ imaginative strategy for reworking customary law and his distinctive approach to the enigma of opinio juris. The discussion then broadens by placing Byers’ book in the expanding dialogue between International Relations and International Law. Here, the article locates the mutual antipathy of the two disciplines in two moments of intellectual hubris: Wilson’s liberal certainty in 1919 and realism’s triumphalism in the immediate post-World War II era. The article then goes on to suggest that, despite a valiant effort, Byers cannot effect a reconciliation between the two disciplines and, in particular, the power of rules and the three theoretical programmes against which he argues: realism, institutionalism and constructivism. Finally, Byers’ book is characterized as a series of skirmishes on the legal theory front; a foray into an increasingly rich, adversarial and robust dialogue about the way to approach the study of international law and the goals one might support within the * Law Department, London School of Economics. -

A Grounded Theory Study of Behavior Patterns Linda Carey Halverson University of St

University of St. Thomas, Minnesota UST Research Online Education Doctoral Dissertations in Organization School of Education Development 2011 Stereotype-Free Mixed Birth Generation Workplaces: A Grounded Theory Study of Behavior Patterns Linda Carey Halverson University of St. Thomas, Minnesota, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.stthomas.edu/caps_ed_orgdev_docdiss Part of the Education Commons Recommended Citation Halverson, Linda Carey, "Stereotype-Free Mixed Birth Generation Workplaces: A Grounded Theory Study of Behavior Patterns" (2011). Education Doctoral Dissertations in Organization Development. 7. https://ir.stthomas.edu/caps_ed_orgdev_docdiss/7 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Education at UST Research Online. It has been accepted for inclusion in Education Doctoral Dissertations in Organization Development by an authorized administrator of UST Research Online. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Stereotype-Free Mixed Birth Generation Workplaces: A Grounded Theory Study of Behavior Patterns A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE SCHOOL OF EDUCATION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF ST. THOMAS By Linda Carey Halverson IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF EDUCATION March 2011 UNIVERSITY OF ST. THOMAS We certify that we have read this dissertation and approved it as adequate in scope and quality. We have found that it is complete and satisfactory in all respects, and that any and all revisions -

The Intern – Ben & Patty – Entire Screenplay.Pdf

THE INTERN by Nancy Meyers January 2014 FADE IN: EXT. PROSPECT PARK - BROOKLYN - AN EARLY SPRING MORNING An eclectic Group ranging in age from 30 to 80 gather in rows performing the ancient Chinese martial art of TAI CHI. They are led by their young and graceful Instructor. CAMERA GLIDES PAST one student to the next, as they move in sync through their meditative poses. CREDITS BEGIN. BEN (V.O.) Freud said, “Love and work, work and love. That’s all there is.” Well, I’m retired and my wife is dead. And on that, we ARRIVE on BEN WHITTAKER. Ben just turned Seventy, an Everyman in many ways, but a unique man to all who know him. He exhales as he turns in sync with the others. BEN (V.O.) -- As you can imagine, that has given me some time on my hands. INT. BEN’S HOUSE - BROOKLYN - NIGHT BEN, wearing a suit and tie, sits in an upright chair in his comfortable brownstone, TALKING TO CAMERA. Looks like he’s on VIDEO. BEN My wife’s been gone for three-and-a- half years. I miss her in every way. And retirement -- that is an ongoing, relentless effort in creativity. At first, I admit, I enjoyed the novelty of it. Sort of felt like I was playing hooky. EXT. JFK TARMAC - NEW YORK CITY - DAY A jumbo jet lifts off. BEN V.O. I used all the miles I had saved and traveled the globe. 2. INT. BEN’S BROWNSTONE - BROOKLYN - NIGHT Ben ENTERS in an overcoat, carrying his suitcase and wearing a purple lei around his neck. -

Sociology in Continental Europe After WWII1

Sociology in Continental Europe after WWII1 Matthias Duller & Christian Fleck Continental particularities Sociology was invented in Europe. For several reasons, however, it did not bloom there for the first one-and-a-half centuries. The inventor of sociology, Auguste Comte, was an independent scholar with no affiliation to any institution. Likewise, other European founding fathers, such as Alexis Tocqueville, Herbert Spencer, Karl Marx, and Friedrich Engels, were not professors, nor were they paid for their scholarly service by the state. Looking at the history of sociology in continental Europe, we do not come upon a striking role model of a “professional sociologist.” What is normally called the classical period ranges from pre-Comtean authors down to the generation after Comte (born 1798): Among the most prominent figures, from Ludwig Gumplowicz (1838), Vilfredo Pareto (1848), Tomáš Masaryk (1850), Maksim Kovalevsky (1851), Ferdinand Tönnies (1855), Georg Simmel (1858), Émile Durkheim (1858), Max Weber (1864), Marcel Mauss (1872), Roberto Michels (1876), Maurice Halbwachs (1977) to Florian Znaniecki (1882), only the Frenchmen and the exiled Pole occupied positions whose descriptions covered sociology and nothing other than sociology. All the others earned their living by practicing different professions or teaching other disciplines. For a very long time sociology failed to appear as a distinct entity in Continental Europe’s academic world. Simply put, one could not study it (even in Durkheim’s France a specialized undergraduate programme, licence de sociologie, started not earlier than 1958, before that students got an multidisciplinary training in the Facultés de Lettres or specialized institutions as the Vth Section of the École pratique des hautes études or the College des France). -

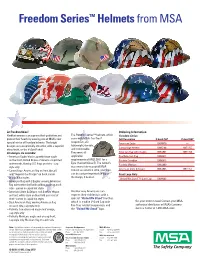

Freedom Series™ Helmetsfrom

Freedom Series™ Helmets from MSA Let Freedom Shine! Ordering Information Hardhat wearers can express their patriotism and The Freedom Series™ helmets, which Freedom Series ® protect their heads by wearing one of MSA’s new come with MSA’s Fas-Trac Full Decoration V-Gard CAP V-Gard HAT suspension, are special series of Freedom helmets. The bright American Eagle 10079479 — designs are exceptionally attractive, with a superior lightweight, durable, Camouflage Helmet 10065166 10071155 shiny finish, on the V-Gard® shell. and comfortable. Six designs are available: They meet all American Flag with 2 Eagles 10052947 10071159 • American Eagle: black cap with large eagle applicable Dual American Flag 10050611 — on the front, United States of America imprinted requirements of ANSI Z89.1 for a Patriotic Canadian 10050613 — Type I helmet (Class E). The helmet’s underneath, flowing U.S. flags on sides - cap Patriotic Mexican 10052600 — style only accessory slots accept all MSA American Stars & Stripes 10052945 10071157 • Camouflage: American flag on front (decal) V-Gard accessories. Also, your logo and “Support Our Troops” on back comes can be custom-imprinted on top of Front Logo Only the design, if desired. in cap & hat styles “United We Stand” V-Gard Cap 10034263 — • American Flag with 2 Eagles: waving American flag over entire shell with golden eagle on each side - comes in cap & hat styles • American Stars & Stripes: red & white stripes Another way Americans can on front, white stars on blue field over rest of express their solidarity is with a shell -comes in cap & hat styles special “United We Stand” hardhat, • Dual American Flag: waving American flag which is a white V-Gard Cap with Get your order in now! Contact your MSA- on each side, cap style only Fas-Trac ratchet suspension, and authorized distributor, or MSA’s Customer • Patriotic Canadian: red maple leaf design, the “United We Stand” logo. -

8123 Songs, 21 Days, 63.83 GB

Page 1 of 247 Music 8123 songs, 21 days, 63.83 GB Name Artist The A Team Ed Sheeran A-List (Radio Edit) XMIXR Sisqo feat. Waka Flocka Flame A.D.I.D.A.S. (Clean Edit) Killer Mike ft Big Boi Aaroma (Bonus Version) Pru About A Girl The Academy Is... About The Money (Radio Edit) XMIXR T.I. feat. Young Thug About The Money (Remix) (Radio Edit) XMIXR T.I. feat. Young Thug, Lil Wayne & Jeezy About Us [Pop Edit] Brooke Hogan ft. Paul Wall Absolute Zero (Radio Edit) XMIXR Stone Sour Absolutely (Story Of A Girl) Ninedays Absolution Calling (Radio Edit) XMIXR Incubus Acapella Karmin Acapella Kelis Acapella (Radio Edit) XMIXR Karmin Accidentally in Love Counting Crows According To You (Top 40 Edit) Orianthi Act Right (Promo Only Clean Edit) Yo Gotti Feat. Young Jeezy & YG Act Right (Radio Edit) XMIXR Yo Gotti ft Jeezy & YG Actin Crazy (Radio Edit) XMIXR Action Bronson Actin' Up (Clean) Wale & Meek Mill f./French Montana Actin' Up (Radio Edit) XMIXR Wale & Meek Mill ft French Montana Action Man Hafdís Huld Addicted Ace Young Addicted Enrique Iglsias Addicted Saving abel Addicted Simple Plan Addicted To Bass Puretone Addicted To Pain (Radio Edit) XMIXR Alter Bridge Addicted To You (Radio Edit) XMIXR Avicii Addiction Ryan Leslie Feat. Cassie & Fabolous Music Page 2 of 247 Name Artist Addresses (Radio Edit) XMIXR T.I. Adore You (Radio Edit) XMIXR Miley Cyrus Adorn Miguel Adorn Miguel Adorn (Radio Edit) XMIXR Miguel Adorn (Remix) Miguel f./Wiz Khalifa Adorn (Remix) (Radio Edit) XMIXR Miguel ft Wiz Khalifa Adrenaline (Radio Edit) XMIXR Shinedown Adrienne Calling, The Adult Swim (Radio Edit) XMIXR DJ Spinking feat.