Zoom Sur Le Robot De Metropolis, Fritz Lang, 1926

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dp-Metropolis-Version-Longue.Pdf

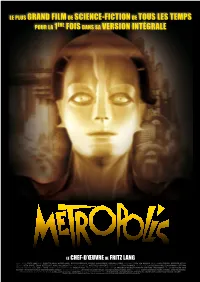

LE PLUS GRAND FILM DE SCIENCE-FICTION DE TOUS LES TEMPS POUR LA 1ÈRE FOIS DANS SA VERSION INTÉGRALE LE CHEf-d’œuvrE DE FRITZ LANG UN FILM DE FRITZ LANG AVEC BRIGITTE HELM, ALFRED ABEL, GUSTAV FRÖHLICH, RUDOLF KLEIN-ROGGE, HEINRICH GORGE SCÉNARIO THEA VON HARBOU PHOTO KARL FREUND, GÜNTHER RITTAU DÉCORS OTTO HUNTE, ERICH KETTELHUT, KARL VOLLBRECHT MUSIQUE ORIGINALE GOTTFRIED HUPPERTZ PRODUIT PAR ERICH POMMER. UN FILM DE LA FRIEDRICH-WILHELM-MURNAU-STIFTUNG EN COOPÉRATION AVEC ZDF ET ARTE. VENTES INTERNATIONALES TRANSIT FILM. RESTAURATION EFFECTUÉE PAR LA FRIEDRICH-WILHELM-MURNAU-STIFTUNG, WIESBADEN AVEC LA DEUTSCHE KINE MATHEK – MUSEUM FÜR FILM UND FERNSEHEN, BERLIN EN COOPÉRATION AVEC LE MUSEO DEL CINE PABLO C. DUCROS HICKEN, BUENOS AIRES. ÉDITORIAL MARTIN KOERBER, FRANK STROBEL, ANKE WILKENING. RESTAURATION DIGITAle de l’imAGE ALPHA-OMEGA DIGITAL, MÜNCHEN. MUSIQUE INTERPRÉTÉE PAR LE RUNDFUNK-SINFONIEORCHESTER BERLIN. ORCHESTRE CONDUIT PAR FRANK STROBEL. © METROPOLIS, FRITZ LANG, 1927 © FRIEDRICH-WILHELM-MURNAU-STIFTUNG / SCULPTURE DU ROBOT MARIA PAR WALTER SCHULZE-MITTENDORFF © BERTINA SCHULZE-MITTENDORFF MK2 et TRANSIT FILMS présentent LE CHEF-D’œuvre DE FRITZ LANG LE PLUS GRAND FILM DE SCIENCE-FICTION DE TOUS LES TEMPS POUR LA PREMIERE FOIS DANS SA VERSION INTEGRALE Inscrit au registre Mémoire du Monde de l’Unesco 150 minutes (durée d’origine) - format 1.37 - son Dolby SR - noir et blanc - Allemagne - 1927 SORTIE EN SALLES LE 19 OCTOBRE 2011 Distribution Presse MK2 Diffusion Monica Donati et Anne-Charlotte Gilard 55 rue Traversière 55 rue Traversière 75012 Paris 75012 Paris [email protected] [email protected] Tél. : 01 44 67 30 80 Tél. -

Close-Up on the Robot of Metropolis, Fritz Lang, 1926

Close-up on the robot of Metropolis, Fritz Lang, 1926 The robot of Metropolis The Cinémathèque's robot - Description This sculpture, exhibited in the museum of the Cinémathèque française, is a copy of the famous robot from Fritz Lang's film Metropolis, which has since disappeared. It was commissioned from Walter Schulze-Mittendorff, the sculptor of the original robot, in 1970. Presented in walking position on a wooden pedestal, the robot measures 181 x 58 x 50 cm. The artist used a mannequin as the basic support 1, sculpting the shape by sawing and reworking certain parts with wood putty. He next covered it with 'plates of a relatively flexible material (certainly cardboard) attached by nails or glue. Then, small wooden cubes, balls and strips were applied, as well as metal elements: a plate cut out for the ribcage and small springs.’2 To finish, he covered the whole with silver paint. - The automaton: costume or sculpture? The robot in the film was not an automaton but actress Brigitte Helm, wearing a costume made up of rigid pieces that she put on like parts of a suit of armour. For the reproduction, Walter Schulze-Mittendorff preferred making a rigid sculpture that would be more resistant to the risks of damage. He worked solely from memory and with photos from the film as he had made no sketches or drawings of the robot during its creation in 1926. 3 Not having to take into account the morphology or space necessary for the actress's movements, the sculptor gave the new robot a more slender figure: the head, pelvis, hips and arms are thinner than those of the original. -

Film Front Weimar: Representations of the First World War in German Films from the Weimar Period (1919-1933) Kester, Bernadette

www.ssoar.info Film Front Weimar: Representations of the First World War in German Films from the Weimar Period (1919-1933) Kester, Bernadette Veröffentlichungsversion / Published Version Monographie / monograph Zur Verfügung gestellt in Kooperation mit / provided in cooperation with: OAPEN (Open Access Publishing in European Networks) Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Kester, B. (2002). Film Front Weimar: Representations of the First World War in German Films from the Weimar Period (1919-1933). (Film Culture in Transition). Amsterdam: Amsterdam Univ. Press. https://nbn-resolving.org/ urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-317059 Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer CC BY-NC-ND Lizenz This document is made available under a CC BY-NC-ND Licence (Namensnennung-Nicht-kommerziell-Keine Bearbeitung) zur (Attribution-Non Comercial-NoDerivatives). For more Information Verfügung gestellt. Nähere Auskünfte zu den CC-Lizenzen finden see: Sie hier: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/deed.de * pb ‘Film Front Weimar’ 30-10-2002 14:10 Pagina 1 The Weimar Republic is widely regarded as a pre- cursor to the Nazi era and as a period in which jazz, achitecture and expressionist films all contributed to FILM FRONT WEIMAR BERNADETTE KESTER a cultural flourishing. The so-called Golden Twenties FFILMILM FILM however was also a decade in which Germany had to deal with the aftermath of the First World War. Film CULTURE CULTURE Front Weimar shows how Germany tried to reconcile IN TRANSITION IN TRANSITION the horrendous experiences of the war through the war films made between 1919 and 1933. -

Present and Future Urban Spaces Cinematically Considered

Exploding Spaces Present and Future Urban Spaces Cinematically Considered University of Cape Town lan-Malcolm Rijsdijk The copyright of this thesis vests in the author. No quotation from it or information derived from it is to be published without full acknowledgement of the source. The thesis is to be used for private study or non- commercial research purposes only. Published by the University of Cape Town (UCT) in terms of the non-exclusive license granted to UCT by the author. University of Cape Town [Abstract] Urban visions in contemporary film considered to be science fiction are, in fundamental ways, not extrapolations from (or even analogies with) the present, but rather derive their extrapolative impetus from the confluence of urban utopianism and the development of the film medium in the first three decades of the twentieth century. This study seeks to understand the visual dynamics of contemporary science fiction cities in film by exploring a number of diverse architectural and cinematic influences. The argument is initiated through a consideration of utopianism and science fiction, before moving onto specific architectural analysis focused on utopian plans from the modernist period, and the growth of New York during the 1920s. Through a brief reading of German Expressionist Cinema in Chapter 3, the spatial and architectural groundwork is laid for the analysis of several films in Chapters 4-6: Disclosure, Blade Runner, Selen, The Devil's Advocate, 12 Monkeys and The Fifth Element. (While not all the films would be considered as science fiction, those non-science fiction films offer provocative readings of the city as a whole). -

* Hc Omslag Film Architecture 22-05-2007 17:10 Pagina 1

* hc omslag Film Architecture 22-05-2007 17:10 Pagina 1 Film Architecture and the Transnational Imagination: Set Design in 1930s European Cinema presents for the first time a comparative study of European film set design in HARRIS AND STREET BERGFELDER, IMAGINATION FILM ARCHITECTURE AND THE TRANSNATIONAL the late 1920s and 1930s. Based on a wealth of designers' drawings, film stills and archival documents, the book FILM FILM offers a new insight into the development and signifi- cance of transnational artistic collaboration during this CULTURE CULTURE period. IN TRANSITION IN TRANSITION European cinema from the late 1920s to the late 1930s was famous for its attention to detail in terms of set design and visual effect. Focusing on developments in Britain, France, and Germany, this book provides a comprehensive analysis of the practices, styles, and function of cine- matic production design during this period, and its influence on subsequent filmmaking patterns. Tim Bergfelder is Professor of Film at the University of Southampton. He is the author of International Adventures (2005), and co- editor of The German Cinema Book (2002) and The Titanic in Myth and Memory (2004). Sarah Street is Professor of Film at the Uni- versity of Bristol. She is the author of British Cinema in Documents (2000), Transatlantic Crossings: British Feature Films in the USA (2002) and Black Narcis- sus (2004). Sue Harris is Reader in French cinema at Queen Mary, University of London. She is the author of Bertrand Blier (2001) and co-editor of France in Focus: Film -

From Iron Age Myth to Idealized National Landscape: Human-Nature Relationships and Environmental Racism in Fritz Lang’S Die Nibelungen

FROM IRON AGE MYTH TO IDEALIZED NATIONAL LANDSCAPE: HUMAN-NATURE RELATIONSHIPS AND ENVIRONMENTAL RACISM IN FRITZ LANG’S DIE NIBELUNGEN Susan Power Bratton Whitworth College Abstract From the Iron Age to the modern period, authors have repeatedly restructured the ecomythology of the Siegfried saga. Fritz Lang’s Weimar lm production (released in 1924-1925) of Die Nibelungen presents an ascendant humanist Siegfried, who dom- inates over nature in his dragon slaying. Lang removes the strong family relation- ships typical of earlier versions, and portrays Siegfried as a son of the German landscape rather than of an aristocratic, human lineage. Unlike The Saga of the Volsungs, which casts the dwarf Andvari as a shape-shifting sh, and thereby indis- tinguishable from productive, living nature, both Richard Wagner and Lang create dwarves who live in subterranean or inorganic habitats, and use environmental ideals to convey anti-Semitic images, including negative contrasts between Jewish stereo- types and healthy or organic nature. Lang’s Siegfried is a technocrat, who, rather than receiving a magic sword from mystic sources, begins the lm by fashioning his own. Admired by Adolf Hitler, Die Nibelungen idealizes the material and the organic in a way that allows the modern “hero” to romanticize himself and, with- out the aid of deities, to become superhuman. Introduction As one of the great gures of Weimar German cinema, Fritz Lang directed an astonishing variety of lms, ranging from the thriller, M, to the urban critique, Metropolis. 1 Of all Lang’s silent lms, his two part interpretation of Das Nibelungenlied: Siegfried’s Tod, lmed in 1922, and Kriemhilds Rache, lmed in 1923,2 had the greatest impression on National Socialist leaders, including Adolf Hitler. -

Heng-Moduleawk7-Metropolis.Pdf

Phone: (02) 8007 6824 DUX Email: [email protected] Web: dc.edu.au 2018 HIGHER SCHOOL CERTIFICATE COURSE MATERIALS HSC English Advanced Module A: Metropolis Term 1 – Week 7 Name ………………………………………………………. Class day and time ………………………………………… Teacher name ……………………………………………... HSC English Advanced - Module A: Metropolis Term 1 – Week 7 1 DUX Term 1 – Week 7 – Theory • Film Analysis • Homework FILM ANALYSIS SEGMENT SIX (THE MACHINE-MAN) After discovering the workers' clandestine meeting, Freder's controlling, glacial father conspires with mad scientist Rotwang to create an evil, robotic Maria duplicate, in order to manipulate his workers and preach riot and rebellion. Fredersen could then use force against his rebellious workers that would be interpreted as justified, causing their self-destruction and elimination. Ultimately, robots would be capable of replacing the human worker, but for the time being, the robot would first put a stop to their revolutionary activities led by the good Maria: "Rotwang, give the Machine-Man the likeness of that girl. I shall sow discord between them and her! I shall destroy their belief in this woman --!" After Joh Fredersen leaves to return above ground, Rotwang predicts doom for Joh's son, knowing that he will be the workers' mediator against his own father: "You fool! Now you will lose the one remaining thing you have from Hel - your son!" Rotwang comes out of hiding, and confronts Maria, who is now alone deep in the catacombs (with open graves and skeletal remains surrounding her). He pursues her - in the expressionistic scene, he chases her with the beam of light from his bright flashlight, then corners her, and captures her when she cannot escape at a dead-end. -

Bertelsmann and UFA Present 'Extended Version' of UFA Film Nights

PRESS RELEASE Bertelsmann and UFA Present ‘Extended Version’ of UFA Film Nights • From 22 to 25 August, early masterpieces of cinema history as well as – for the first time – a contemporary UFA movie will be screened in the open air accompanied by live music • Premiere of the digitized version of the silent movie classics “Die Liebe der Jeanne Ney” (The Love of Jeanne Ney), “Metropolis,” and “Der letzte Mann” (The Last Laugh) with new score • Live musical accompaniment by Jeff Mills, the WDR Radio Orchestra, the Neues Kammerorchester Potsdam and Deutsche Oper Berlin’s UFA Brass • Maria Furtwängler, Tom Schilling, Katharina Wackernagel and Franz Dinda introduce the UFA Film Nights • Tickets now available Berlin, July 12, 2017 – Bertelsmann and UFA will present the UFA Film Nights in Berlin for the seventh time from August 22 to 25, 2017. This year, early masterpieces of cinema history as well as a contemporary box office hit from UFA – to mark the centenary of Germany’s leading film production company – will be screened in the open air against a spectacular backdrop and accompanied by live music. The UFA Film Nights have become a cinematic-musical highlight of Berlin’s cultural summer with a dedicated stage orchestra and big screen erected for the occasion in the Kolonnadenhof on Museum Island, a World Cultural Heritage site. The international media company Bertelsmann and UFA thus continue their tradition of presenting silent movie classics in a historic architectural setting. As in previous years, more than 800 guests are expected to attend each evening. Following a reception at Bertelsmann Unter den Linden 1, Berlin, the UFA Film Nights open on August 22nd with Georg Wilhelm Pabst's “Die Liebe der Jeanne Ney” (“The Love of Jeanne Ney”) an exciting melodrama set during the October Revolution. -

DCP – Film Distribution 09/2018

DCP – Film distribution 09/2018 Friedrich-Wilhelm-Murnau-Stiftung Murnaustraße 6 65189 Wiesbaden Film distribution Patricia Heckert phone.: +49 (0) 611 / 9 77 08 - 45 Fax: +49 (0) 611 / 9 77 08 - 19 [email protected] Friedrich-Wilhelm-Murnau-Stiftung Film distribution (DCP) 09/2018 Film title / Year Silent film / Music Type Credits Languages / Length Subtitles Abschied sound film directed by: Robert Siodmak german 77'25" DE 1930 cast: Brigitte Horney, Aribert Mog, Emilie alternate ending on DCP Unda Akrobat Schö-ö-ö-n sound film directed by: Wolfgang Staudte german 84'06'' DE 1943 cast: Charlie Rivell, Clara Tabody, Karl Schönböck, Fritz Kampers Als ich tot war music: Aljoscha Zimmermann silent film directed by: Ernst Lubitsch german intertitles 37'43" DE 1915 arrangement: Sabrina Hausmann cast: Ernst Lubitsch, Helene Voß tinted ensemble: Sabrina Hausmann, Mark Pogolski Amphitryon sound film directed by: Reinhold Schünzel german 103'11" DE 1935 cast: Willy Fritsch, Paul Kemp, Lilian Harvey Anna Boleyn music: Javier Pérez de Azpeitia silent film directed by: Ernst Lubitsch german intertitles 123'47" DE 1920 cast: Emil Jannings, Henny Porten, tinted Paul Hartmann restoration 1998 Apachen von Paris, Die without music silent film director: Nikolai Malikoff german intertitles 108'08'' DE 1927 cast: Jaque Catelain, Lia Eibenschütz, Olga Limburg Asphalt music: Karl-Ernst Sasse without mus directed by: Joe May german intertitles 94'14'' DE 1929 recording: Brandenburgische Philharmonie cast: Betty Amann, Gustav Fröhlich, Albert restoration -

Metropolis Um Filme De Fritz Lang 1927

CICLO INTEGRADO DE CINEMA, DEBATES E COLÓQUIOS NA FEUC DOC TAGV / FEUC INTEGRAÇÃO MUNDIAL, DESINTEGRAÇÃO NACIONAL: A CRISE NOS MERCADOS DE TRABALHO METROPOLIS UM FILME DE FRITZ LANG 1927 CICLO INTEGRADO DE CINEMA, DEBATES E COLÓQUIOS NA FEUC DOC TAGV / FEUC INTEGRAÇÃO MUNDIAL, DESINTEGRAÇÃO NACIONAL: A CRISE NOS MERCADOS DE TRABALHO http://www4.fe.uc.pt/ciclo_int/2007_2008.htm SESSÃO 14 (SESSÃO DE ENCERRAMENto) METROPOLIS: UMA ANTEVISÃO DA EUROPA ACTUAL? METROPOLIS (1927) UM FILME DE FRITZ LANG DEBate COM: JEAN-MICHEL MEURICE (CINeasta) MANUEL PORTELA (FLUC) JOSÉ ANTÓNIO BANDEIRINHA (PRÓ-REItoR UC) TeatRO ACADÉMICO DE GIL VICENTE 2 DE JULHO DE 2008 METROPOLIS: UMA ANTEVISÃO DA EUROPA ACTUAL? 1. METROPOLIS: A VISÃO DE ALGUNS cineastas 05 1.1. METROPOLIS, Visto POR FRITZ Lang 05 1.2. METROPOLIS, Visto POR Bunuel 08 1.3. METROPOLIS, Visto POR JOÃO BÉNARD DA Costa 11 1.4. Relatos DE UMA REALIZAÇÃo 15 2. LANG, METROPOLIS E A DIMENSÃO POLÍtica 17 2.1. METROPOLIS: UM FILME INTEMPoral 17 2.2. A LEITURA POLÍTICA DE UMA cena 30 3. METROPOLIS: ALGUMAS RECENSÕes 31 3.1. METROPOLIS, DE FRITZ Lang 31 3.2. METROPOLIS, SINOPse 35 3.3. METROPOLIS: O FILME MAIS INOVADOR DESDE A INVENÇÃO DO CINEMa 39 3.4. METROPOLIS: ALGUMAS BRECHas 41 3.5. COMENTÁRIOS DO LE MONDE SOBRE METROPOLIS 43 4. A FUGA DE Lang 48 5. METROPOLIS: UMA LEITURA DE SÍntese 50 CICLO INTEGRADO DE CINEMA, DEBATES E COLÓQUIOS NA FEUC DOC TAGV / FEUC INTEGRAÇÃO MUNDIAL, DESINTEGRAÇÃO NACIONAL: A CRISE NOS MERCADOS DE TRABALHO PROGRAMA 2007 - 2008 60 © Metropolis, 1927. METROPOLIS: UMA ANTEVISÃO DA EUROPA ACTUAL? 1. -

Cinema 2: the Time-Image

m The Time-Image Gilles Deleuze Translated by Hugh Tomlinson and Robert Caleta M IN University of Minnesota Press HE so Minneapolis fA t \1.1 \ \ I U III , L 1\) 1/ ES I /%~ ~ ' . 1 9 -08- 2000 ) kOTUPHA\'-\t. r'Y'f . ~ Copyrigh t © ~1989 The A't1tl ----resP-- First published as Cinema 2, L1111age-temps Copyright © 1985 by Les Editions de Minuit, Paris. ,5eJ\ Published by the University of Minnesota Press III Third Avenue South, Suite 290, Minneapolis, MN 55401-2520 f'tJ Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper 1'::>55 Fifth printing 1997 :])'''::''531 ~ Library of Congress Number 85-28898 ISBN 0-8166-1676-0 (v. 2) \ ~~.6 ISBN 0-8166-1677-9 (pbk.; v. 2) IJ" 2. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or othenvise, ,vithout the prior written permission of the publisher. The University of Minnesota is an equal-opportunity educator and employer. Contents Preface to the English Edition Xl Translators'Introduction XV Chapter 1 Beyond the movement-image 1 How is neo-realism defined? - Optical and sound situations, in contrast to sensory-motor situations: Rossellini, De Sica - Opsigns and sonsigns; objectivism subjectivism, real-imaginary - The new wave: Godard and Rivette - Tactisigns (Bresson) 2 Ozu, the inventor of pure optical and sound images Everyday banality - Empty spaces and stilllifes - Time as unchanging form 13 3 The intolerable and clairvoyance - From cliches to the image - Beyond movement: not merely opsigns and sonsigns, but chronosigns, lectosigns, noosigns - The example of Antonioni 18 Chapter 2 ~ecaPitulation of images and szgns 1 Cinema, semiology and language - Objects and images 25 2 Pure semiotics: Peirce and the system of images and signs - The movement-image, signaletic material and non-linguistic features of expression (the internal monologue). -

Angel Sings the Blues: Josef Von Sternberg's the Blue Angel in Context

FILMHISTORIA Online Vol. 30, núm. 2 (2020) · ISSN: 2014-668X REVIEW ESSAYS . Angel Sings the Blues: Josef von Sternberg’s The Blue Angel in Context ROBERT J. CARDULLO University of Michigan Abstract This essay reconsiders The Blue Angel (1930) not only in light of its 2001 restoration, but also in light of the following: the careers of Josef von Sternberg, Emil Jannings, and Marlene Dietrich; the 1905 novel by Heinrich Mann from which The Blue Angel was adapted; early sound cinema; and the cultural-historical circumstances out of which the film arose. In The Blue Angel, Dietrich, in particular, found the vehicle by which she could achieve global stardom, and Sternberg—a volatile man of mystery and contradiction, stubbornness and secretiveness, pride and even arrogance—for the first time found a subject on which he could focus his prodigious talent. Keywords: The Blue Angel, Josef von Sternberg, Emil Jannings, Marlene Dietrich, Heinrich Mann, Nazism. Resumen Este ensayo reconsidera El ángel azul (1930) no solo a la luz de su restauración de 2001, sino también a la luz de lo siguiente: las carreras de Josef von Sternberg, Emil Jannings y Marlene Dietrich; la novela de 1905 de Heinrich Mann de la cual se adaptó El ángel azul; cine de sonido temprano; y las circunstancias histórico-culturales de las cuales surgió la película. En El ángel azul, Dietrich, en particular, encontró el vehículo por el cual podía alcanzar el estrellato global, y Sternberg, un hombre volátil de misterio y contradicción, terquedad y secretismo, orgullo e incluso arrogancia, por primera vez encontró un tema en el que podía enfocar su prodigioso talento.