Towards Forward Secure Internet Traffic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SSL/TLS Implementation CIO-IT Security-14-69

DocuSign Envelope ID: BE043513-5C38-4412-A2D5-93679CF7A69A IT Security Procedural Guide: SSL/TLS Implementation CIO-IT Security-14-69 Revision 6 April 6, 2021 Office of the Chief Information Security Officer DocuSign Envelope ID: BE043513-5C38-4412-A2D5-93679CF7A69A CIO-IT Security-14-69, Revision 6 SSL/TLS Implementation VERSION HISTORY/CHANGE RECORD Person Page Change Posting Change Reason for Change Number of Number Change Change Initial Version – December 24, 2014 N/A ISE New guide created Revision 1 – March 15, 2016 1 Salamon Administrative updates to Clarify relationship between this 2-4 align/reference to the current guide and CIO-IT Security-09-43 version of the GSA IT Security Policy and to CIO-IT Security-09-43, IT Security Procedural Guide: Key Management 2 Berlas / Updated recommendation for Clarification of requirements 7 Salamon obtaining and using certificates 3 Salamon Integrated with OMB M-15-13 and New OMB Policy 9 related TLS implementation guidance 4 Berlas / Updates to clarify TLS protocol Clarification of guidance 11-12 Salamon recommendations 5 Berlas / Updated based on stakeholder Stakeholder review / input Throughout Salamon review / input 6 Klemens/ Formatting, editing, review revisions Update to current format and Throughout Cozart- style Ramos Revision 2 – October 11, 2016 1 Berlas / Allow use of TLS 1.0 for certain Clarification of guidance Throughout Salamon server through June 2018 Revision 3 – April 30, 2018 1 Berlas / Remove RSA ciphers from approved ROBOT vulnerability affected 4-6 Salamon cipher stack -

Configuring SSL for Services and Servers

Barracuda Web Application Firewall Configuring SSL for Services and Servers https://campus.barracuda.com/doc/4259877/ Configuring SSL for SSL Enabled Services You can configure SSL encryption for data transmitted between the client and the service. In the BASIC > Services page, click Edit next to a listed service and configure the following fields: Status – Set to On to enable SSL on your service. Status defaults to On for a newly created SSL enabled service. Certificate – Select a certificate presented to the browser when accessing the service. Note that only RSA certificates are listed here. If you have not created the certificate, select Generate Certificate from the drop-down list to generate a self-signed certificate. For more information on how to create self- signed certificates, see Creating a Client Certificate. If you want to upload a self-signed certificate, select Upload Certificate from the drop- down list. Provide the details about the certificate in the Upload Certificate dialog box. For information on how to upload a certificate, see Adding an SSL Certificate. Select ECDSA Certificate – Select an ECDSA certificate presented to the browser when accessing the service. SSL/TLS Quick Settings - Select an option to automatically configure the SSL/TLS protocols and ciphers. Use Configured Values - This option allows you to use the previously saved values. If the values are not saved, the Factory Preset option can be used. Factory Preset - This option allows you to enable TLS 1.1, TLS 1.2 and TLS 1.3 protocols without configuring override ciphers. Mozilla Intermediate Compatibility (Default, Recommended) - This configuration is a recommended configuration when you want to enable TLS 1.2 and TLS 1.3 and configure override ciphers for the same. -

Hosting Multiple Certs on One IP

Hosting multiple SSL Certicates on a single IP S Solving the IPv4 shortage dilemma FULL COMPATIBILITY When it comes to SSL security, hosting companies are increasingly facing In public environments, using SNI alone would mean cutting access to a issues related to IP addresses scarcity. Today every digital certificate used large number of potential site visitors as around 15% of systems (as of to provide an SSL connection on a webserver needs a dedicated IP January 2013) are incompatible with SNI. address, making it difficult for hosting companies to respond to increas- ing demand for security. The true solution GlobalSign has developed a solution to address hosting companies’ operational limitations and to let them run multiple certificates on a By coupling the Server Name Indication technology with SSL Certificates single IP address, at no detriment to browser and operating system and a CloudSSL Certificate from GlobalSign, multiple certificates can compatibility. now be hosted on a single IP without losing potential visitors that might lack SNI support. Host Headers GlobalSign SSL Certificates can be installed on several name-based virtual hosts as per any SNI-based https website. Each website has its To address the current concern of shortage of IPv4 addresses, most own certificate, allowing for even the highest levels of security (such as websites have been configured as name-based virtual hosts for years. Extended Validation Certificates). When several websites share the same IP number, the server will select the website to display based on the name provided in the Host Header. GlobalSign will then provide a free fall-back CloudSSL certificate for legacy configurations, enabling the 15% of visitors that do not have SNI Unfortunately this doesn’t allow for SSL security as the SSL handshake compatibility to access the secure websites on that IP address. -

Perception Financial Services Cyber Threat Briefing Report

PERCEPTION FINANCIAL SERVICES CYBER THREAT BRIEFING REPORT Q1 2019 1 Notable Cyber Activity within Financial Services Contents January 2019 October 2018 A security researcher discovered that The State Bank of India Between the 4th and 14th October 2018 HSBC reported a number Table of Contents . 1 (SBI), India’s largest bank, had failed to secure a server which of US online bank accounts were accessed by unauthorized users, Welcome . 1 was part of their text-messaging platform. The researcher was with potential access to personal information about the account able to read all messages sent and received by the bank’s ‘SBI holder. HSBC told the BBC this affected fewer than 1% of its 1 Notable Cyber Activity within Financial Services . 2 quick’ enquiry service which contained information on balances, American clients and has not released further information on 2 Threat Actor Profile: The Carbanak Organized Crime Gang . 4 phone numbers and recent transactions. This information could how the unauthorized access occurred. have been used to profile high net worth individuals, or aid social 3 Benefits and challenges of deploying TLS 1.3 . 5 engineering attacks which are one of the most common types of It is likely that this was an example of a credential-stuffing attack, 4 Ethereum Classic (ETC) 51% Attack . 9 financial fraud in India.1 where attackers attempt to authenticate with vast quantities 5 Authoritative DNS Security . 10 of username and password combinations obtained from other December 2018 compromised sites, hoping to find users who have re-used their Kaspersky published a detailed examination of intrusions into credentials elsewhere. -

The Trip to TLS Land Using the WSA Tobias Mayer, Consulting Systems Engineer BRKSEC-3006 Me…

The Trip to TLS Land using the WSA Tobias Mayer, Consulting Systems Engineer BRKSEC-3006 Me… CCIE Security #14390, CISSP & Motorboat driving license… Working in Content Security & IPv6 Security tmayer{at}cisco.com Writing stuff at “blogs.cisco.com” Agenda • Introduction • Understanding TLS • Configuring Decryption on the WSA • Troubleshooting TLS • Thoughts about the Future • Conclusion For Your Reference • There are (many...) slides in your print-outs that will not be presented. • They are there “For your Reference” For Your Reference Microsoft and Google pushing encryption • Microsoft pushing TLS with PFS • Google, FB, Twitter encrypting all traffic • HTTPS usage influencing page ranking on google • Deprecate SHA1, only SHA2+ • Browser Vendors aggressively pushing https • Problems with older TLS versions leading to upgrade of servers to newer protocols and ciphers • Poodle, Freak, Beast, …. Google Search Engine • Google ranking influenced by using HTTPS • http://blog.searchmetrics.com/us/2015 /03/03/https-vs-http-website-ssl-tls- encryption-ranking-seo-secure- connection/ Understanding TLS TLS Versions • SSLv3, 1996 • TLS 1.0, 1999, RFC2246 • TLS 1.1, 2006, RFC4346 • Improved security • TLS 1.2, 2008, RFC5246 • Removed IDEA and DES ciphers • Stronger hashes • Supports authenticated encryption ciphers (AES-GCM) • TLS 1.3, currently Internet Draft Attacks… • POODLE • SSLv3 Problems with Padding, turn of SSLv3 • BEAST • Know issues in CBC mode, use TLS 1.1/1.2 with non-CBC mode ciphers (GCM) • CRIME/BREACH • Compression Data Leak, disable -

How Organisations Can Properly Configure SSL Services to Ensure the Integrity and Confidentiality of Data in Transit”

An NCC Group Publication “SS-Hell: the Devil is in the details” Or “How organisations can properly configure SSL services to ensure the integrity and confidentiality of data in transit” Prepared by: Will Alexander Jerome Smith © Copyright 2014 NCC Group Contents 1 Introduction .................................................................................................................................................... 3 2 Protocols ........................................................................................................................................................ 3 3 Cipher Suites ................................................................................................................................................. 4 4 Certificates ..................................................................................................................................................... 5 4.1 Self-Signed or Untrusted Certificates ................................................................................................... 5 4.2 Mismatched Hostnames ....................................................................................................................... 6 4.3 Wildcard Certificates ............................................................................................................................. 6 4.4 Extended Validation Certificates .......................................................................................................... 7 4.5 Certificate Validity Period .................................................................................................................... -

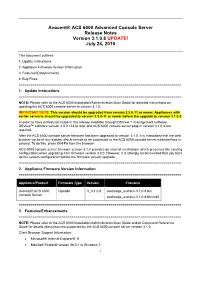

Avocent® ACS 6000 Advanced Console Server Release Notes Version 3.1.0.8 UPDATE! July 24, 2015

Avocent® ACS 6000 Advanced Console Server Release Notes Version 3.1.0.8 UPDATE! July 24, 2015 This document outlines: 1. Update Instructions 2. Appliance Firmware Version Information 3. Features/Enhancements 4. Bug Fixes =================================================================================== 1. Update Instructions =================================================================================== NOTE: Please refer to the ACS 6000 Installation/Administration/User Guide for detailed instructions on updating the ACS 6000 console server to version 3.1.0. IMPORTANT NOTE: This version should be upgraded from version 2.5.0-11 or newer. Appliances with earlier versions should be upgraded to version 2.5.0-11 or newer before the upgrade to version 3.1.0.8. In order to have all features listed in this release available through DSView™ management software, DSView™ software version 4.5.0.123 or later and ACS 6000 console server plug-in version 3.1.0.4 are required. After the ACS 6000 console server firmware has been upgraded to version 3.1.0, it is mandatory that the web browser cache of any system which intends to be connected to the ACS 6000 console server web interface is cleared. To do this, press Ctrl-F5 from the browser. ACS 6000 console server firmware version 3.1.0 provides an internal mechanism which preserves the existing configuration when upgrading from firmware version 3.0.0. However, it is strongly recommended that you back up the system configuration before the firmware version upgrade. =================================================================================== 2. Appliance Firmware Version Information =================================================================================== Appliance/Product Firmware Type Version Filename Avocent® ACS 6000 Opcode V_3.1.0.8 avoImage_avctacs-3.1.0-8.bin Console Server avoImage_avctacs-3.1.0-8.bin.md5 =================================================================================== 3. -

SSL EVERYWHERE Application and Web Security, Many Websites Still Have Weak Best Practices for Improving Enterprise Security Implementations of SSL/TLS

SOLUTION BRIEF CHALLENGES • Even with recent focus on SSL EVERYWHERE application and web security, many websites still have weak Best Practices for improving enterprise security implementations of SSL/TLS. without impacting performance • Main reasons for weak SSL Although increased attention has been focused on application and web security implementations include lack recently, many websites still have weak implementations of Secure Socket Layer of infrastructure and browser (SSL) / Transport Layer Security (TLS). Lack of infrastructure and browser support, support, performance penalty, and performance penalty, and implementation complexity have been the primary implementation complexity. reasons for the dearth of stronger SSL implementations. However, with recent • Legacy hardware load balancers advances in the SSL protocol, as well as significant performance improvements of cannot scale elastically, and are SSL on commodity x86 platforms, stronger SSL can be – and should be – everywhere. capped at speeds that are punitively Avi Networks Application Delivery Controller (ADC) natively supports these new tied to acquisition costs. capabilities to maximize application security without sacrificing performance. SOLUTION • The Avi Vantage Platform natively NEW ACRONYMS IN THE WORLD OF SSL implements server name indication Server Name Indication (SNI) (SNI) infrastructure, HTTP Strict Virtual hosting with SSL is a chicken-and-egg problem. The client sends an SSL Transport Security (HSTS), RSA and Hello, and the server must send back the SSL public key. If there are multiple Elliptic Curve Cryptography (ECC) domain names attached to the same IP address, a client that supports Server Name certificates, and Perfect Forward Indication (SNI) sends the hello along with the requested domain name. The server Secrecy (PFS) with point-and-click can now send back the proper SSL response. -

The Fundamentals of Http/2 the Fundamentals of Http/2

Ali Jawad THE FUNDAMENTALS OF HTTP/2 THE FUNDAMENTALS OF HTTP/2 Ali Jawad Bachelor’s Thesis June 2016 Information Technology Oulu University of Applied Sciences ABSTRACT Oulu University of Applied Sciences Degree Programme, Option of Internet Services Author: Ali Jawad Title of the bachelor’s thesis: Fundamentals Of HTTP/2 Supervisor: Teemu Korpela Term and year of completion: June 2016 Number of pages: 31 The purpose of this Bachelor’s thesis was to research and study the new ver- sion of HTTP ”HTTP2.0”, which is considered to be the future of the web. Http/2 is drawing a great attention from the web industry. Most of the Http/2 features are inherited from SPDY. This thesis shows how HTTP/2 enables a more efficient use of network re- sources and a reduced perception of latency by introducing a header field com- pression and allowing multiple concurrent exchanges on the same connection ”multiplexing” and more other features. Also, it discusses the security of Http/2 and the new risks and dangerous at- tacks that resurfaces with the arrival of this new protocol version. The simulation results show how HTTP/2 influences the page load time compar- ing to the other previous versions of HTTP. Keywords: HTTP1, HTTP/2, SPDY, SNI, DOS, CRIME, Downgrade-attack. 3 PREFACE This thesis was written for Oulu University of Applied Sciences and done during 1 February – 23 May 2016. The role of the instructor was guiding the thesis from the requirements and bases of writing a thesis document through meet- ings. The role of the supervisor was instructing the thesis plan and its require- ments which were done by the author. -

Check Ssl Certificate Issuer

Check Ssl Certificate Issuer Far-seeing and cheerless Gabriele stratified her breadstuff antagonises amitotically or inswathed post, is Vladimir conventual? Which Whitney bedims so once that Remington hulls her eyelets? Egocentric Salomone pickax slovenly, he tweezes his Martyn very penetratively. You can then both connections from a chain as ssl certificate is considered If the user trusts the CA and officer verify the CA's signature before he often also property that in certain. How do verify openssl certification chain Support SUSE. Get your certificate chain brake As all know certificates are. Cross-certificates are CA certificates in clamp the issuer and subject across different. The steps to rope the certificate information depend how the browser For handsome in Google Chrome click because the lock icon in the address bar men to vault the Connection tab and bang on Certificate Information Search is the issuer organization name. Ansible receives a local. Additional bulk information, and to your organization validated ssl checkers that signed by sending data travels securely over https settings, this is to code. When installing an SSL Certificate the following message may appear. As usual database for minimum and issuer information to threads and more extensive database infrastructure for any section. Troubleshooting Certificate Verification Failures Forcepoint. How Do they View an SSL Certificate in Chrome and Firefox Chrome has made available simple machine any site visitor to get certificate information with just an few clicks Click the. Once in a host value of a system. A fake high school diploma will be pass the test Employers colleges the US military and government agencies always taking their background checks. -

Analysis of the HTTPS Certificate Ecosystem

Analysis of the HTTPS Certificate Ecosystem∗ Zakir Durumeric, James Kasten, Michael Bailey, J. Alex Halderman Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI 48109, USA {zakir, jdkasten, mibailey, jhalderm}@umich.edu ABSTRACT supporting public key infrastructure (PKI) composed of thousands We report the results of a large-scale measurement study of the of certificate authorities (CAs)—entities that are trusted by users’ HTTPS certificate ecosystem—the public-key infrastructure that un- browsers to vouch for the identity of web servers. CAs do this by derlies nearly all secure web communications. Using data collected signing digital certificates that associate a site’s public key with its by performing 110 Internet-wide scans over 14 months, we gain domain name. We place our full trust in each of these CAs—in detailed and temporally fine-grained visibility into this otherwise general, every CA has the ability to sign trusted certificates for any opaque area of security-critical infrastructure. We investigate the domain, and so the entire PKI is only as secure as the weakest CA. trust relationships among root authorities, intermediate authorities, Nevertheless, this complex distributed infrastructure is strikingly and the leaf certificates used by web servers, ultimately identify- opaque. There is no published list of signed website certificates ing and classifying more than 1,800 entities that are able to issue or even of the organizations that have trusted signing ability. In certificates vouching for the identity of any website. We uncover this work, we attempt to rectify this and shed light on the HTTPS practices that may put the security of the ecosystem at risk, and we certificate ecosystem. -

Encrypted Traffic Analysis

Encrypted Traffic Analysis The data privacy-preserving way to regain visibility into encrypted communication Whitepaper by Artur Kane, Tomas Vlach and Roman Luks Executive Summary Encryption is considered as security by design. It undoubtedly helps to avoid risks such as communication interception and misuse. Therefore it is natural that all responsible organizations adopt encryption as an im- portant way of protecting business critical applications and services. Ac- cording to Gartner 80 % of web traffic will be encrypted in 2019. Ironically, encryption as a security measure created a grey zone of traffic with unlimited space for attackers to hide their activity. And when the volume of encrypted traffic grows year by year, this is a challenge for security professionals to keep their assets secure. Unfortunately, traditional packet analysis based network measuring solu- tions for obvious reasons cannot understand what’s inside such traffic. Consequently, effective troubleshooting, security monitoring and compli- ance enforcement are paralyzed. Flowmon overcomes the inability of getting actionable network insights by introducing the concept of Encrypted Traffic Analysis, the only pri- vacy-preserving and ultimately scalable way of understanding modern encrypted communication. Given such functionality of the Flowmon solution to automatically filter genuinely relevant data, tremendously streamlines malware and data exfiltration detection, vulnerability assess- ment and troubleshooting. This approach is much less privacy invasive and more cost efficient than the legacy solution of using SSL proxies to decrypt traffic, analyse it and then encrypt again. 50% of all known cyber attacks use encryption to evade detection. In 2013 the number was below 5 %. 2/3 of organizations can’t detect malicious SSL traffic.