Semi-Aquatic Adaptations in a Spinosaur from the Lower Cretaceous of Brazil

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

JVP 26(3) September 2006—ABSTRACTS

Neoceti Symposium, Saturday 8:45 acid-prepared osteolepiforms Medoevia and Gogonasus has offered strong support for BODY SIZE AND CRYPTIC TROPHIC SEPARATION OF GENERALIZED Jarvik’s interpretation, but Eusthenopteron itself has not been reexamined in detail. PIERCE-FEEDING CETACEANS: THE ROLE OF FEEDING DIVERSITY DUR- Uncertainty has persisted about the relationship between the large endoskeletal “fenestra ING THE RISE OF THE NEOCETI endochoanalis” and the apparently much smaller choana, and about the occlusion of upper ADAM, Peter, Univ. of California, Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA; JETT, Kristin, Univ. of and lower jaw fangs relative to the choana. California, Davis, Davis, CA; OLSON, Joshua, Univ. of California, Los Angeles, Los A CT scan investigation of a large skull of Eusthenopteron, carried out in collaboration Angeles, CA with University of Texas and Parc de Miguasha, offers an opportunity to image and digital- Marine mammals with homodont dentition and relatively little specialization of the feeding ly “dissect” a complete three-dimensional snout region. We find that a choana is indeed apparatus are often categorized as generalist eaters of squid and fish. However, analyses of present, somewhat narrower but otherwise similar to that described by Jarvik. It does not many modern ecosystems reveal the importance of body size in determining trophic parti- receive the anterior coronoid fang, which bites mesial to the edge of the dermopalatine and tioning and diversity among predators. We established relationships between body sizes of is received by a pit in that bone. The fenestra endochoanalis is partly floored by the vomer extant cetaceans and their prey in order to infer prey size and potential trophic separation of and the dermopalatine, restricting the choana to the lateral part of the fenestra. -

A New Angiosperm from the Crato Formation (Araripe Basin, Brazil) and Comments on the Early Cretaceous Monocotyledons

Anais da Academia Brasileira de Ciências (2014) 86(4): 1657-1672 (Annals of the Brazilian Academy of Sciences) Printed version ISSN 0001-3765 / Online version ISSN 1678-2690 http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/0001-3765201420140339 www.scielo.br/aabc A new angiosperm from the Crato Formation (Araripe Basin, Brazil) and comments on the Early Cretaceous Monocotyledons FLAVIANA J. DE LIMA1, ANTÔNIO A.F. SARAIVA2, MARIA A.P. DA SILVA3, RENAN A.M. BANTIM1 and JULIANA M. SAYÃO4 1Programa de Pós-Graduação em Geociências, Centro de Tecnologia e Geociências, Universidade Federal de Pernambuco, Av. Acadêmico Hélio Ramos, s/n, Cidade Universitária, 50740-530 Recife, PE, Brasil 2Laboratório de Paleontologia, Universidade Regional do Cariri, Rua Carolino Sucupira, s/n, 63100-000 Crato, CE, Brasil 3Laboratório de Botânica Aplicada, Universidade Regional do Cariri, Rua Carolino Sucupira, s/n, 63100-000 Crato, CE, Brasil 4Laboratório de Biodiversidade do Nordeste, Universidade Federal de Pernambuco, Rua do Alto Reservatório, s/n, Bela Vista, 55608-680 Vitória de Santo Antão, PE, Brasil Manuscript received on July 1, 2014; accepted for publication on September 9, 2014 ABSTRACT The Crato Formation paleoflora is one of the few equatorial floras of the Early Cretaceous. It is diverse, with many angiosperms, especially representatives of the clades magnoliids, monocotyledons and eudicots, which confirms the assumption that angiosperm diversity during the last part of the Early Cretaceous was reasonably high. The morphology of a new fossil monocot is studied and compared to all other Smilacaceae genus, especially in the venation. Cratosmilax jacksoni gen. et sp. nov. can be related to the Smilacaceae family, becoming the oldest record of the family so far. -

Evidence of a New Carcharodontosaurid from the Upper Cretaceous of Morocco

http://app.pan.pl/SOM/app57-Cau_etal_SOM.pdf SUPPLEMENTARY ONLINE MATERIAL FOR Evidence of a new carcharodontosaurid from the Upper Cretaceous of Morocco Andrea Cau, Fabio Marco Dalla Vecchia, and Matteo Fabbri Published in Acta Palaeontologica Polonica 2012 57 (3): 661-665. http://dx.doi.org/10.4202/app.2011.0043 SOM1. PHYLOGENETIC ANALYSIS Material and Methods The data set of the phylogenetic analysis includes 37 Operational Taxonomic Units (OTUs) (35 ingroup neotheropod taxa, including one based on MPM 2594; and two basal theropod outgroups, Herrerasaurus and Tawa), and 808 character statements (see S2 and S3, below). The phylogenetic analyses were conducted through PAUP* vers. 4.010b (Swofford 2002). In the analysis, Herrerasaurus was used as root of the tree. The tree search strategy follows Benson (2009). The analysis initially performed a preliminary search using PAUPRat (Sikes and Lewis 2001). The unique topologies among the most parsimonious trees (MPTs) resulted after the preliminary search were used as a starting point for 1000 tree-bisection-reconnection branch swapping heuristic searches using PAUP*. Included taxa (and source for codings) Outgroup Herrerasaurus (Sereno 1993; Sereno and Novas 1993; Novas 1994; Sereno 2007) Tawa (Nesbitt et al. 2009) Ingroup Abelisaurus (Bonaparte and Novas 1985; Carrano and Sampson 2008) Acrocanthosaurus (Stoval and Landston 1950; Harris 1998; Currie and Carpenter 2000; Eddy and Clarke 2011) Allosaurus (Gilmore 1920; Madsen 1976) Baryonyx (Charig and Milner 1997; Mateus et al. 2010) Carcharodontosaurus (Stromer 1931; Sereno et al. 1996; Brusatte and Sereno 2007) Carnotaurus (Bonaparte et al. 1990) Ceratosaurus (Gilmore 1920; Madsen and Welles 2000). Compsognathus (Peyer 2006) Cryolophosaurus (Smith et al. -

Asteroid Impact, Not Volcanism, Caused the End-Cretaceous Dinosaur Extinction

Asteroid impact, not volcanism, caused the end-Cretaceous dinosaur extinction Alfio Alessandro Chiarenzaa,b,1,2, Alexander Farnsworthc,1, Philip D. Mannionb, Daniel J. Luntc, Paul J. Valdesc, Joanna V. Morgana, and Peter A. Allisona aDepartment of Earth Science and Engineering, Imperial College London, South Kensington, SW7 2AZ London, United Kingdom; bDepartment of Earth Sciences, University College London, WC1E 6BT London, United Kingdom; and cSchool of Geographical Sciences, University of Bristol, BS8 1TH Bristol, United Kingdom Edited by Nils Chr. Stenseth, University of Oslo, Oslo, Norway, and approved May 21, 2020 (received for review April 1, 2020) The Cretaceous/Paleogene mass extinction, 66 Ma, included the (17). However, the timing and size of each eruptive event are demise of non-avian dinosaurs. Intense debate has focused on the highly contentious in relation to the mass extinction event (8–10). relative roles of Deccan volcanism and the Chicxulub asteroid im- An asteroid, ∼10 km in diameter, impacted at Chicxulub, in pact as kill mechanisms for this event. Here, we combine fossil- the present-day Gulf of Mexico, 66 Ma (4, 18, 19), leaving a crater occurrence data with paleoclimate and habitat suitability models ∼180 to 200 km in diameter (Fig. 1A). This impactor struck car- to evaluate dinosaur habitability in the wake of various asteroid bonate and sulfate-rich sediments, leading to the ejection and impact and Deccan volcanism scenarios. Asteroid impact models global dispersal of large quantities of dust, ash, sulfur, and other generate a prolonged cold winter that suppresses potential global aerosols into the atmosphere (4, 18–20). These atmospheric dinosaur habitats. -

From the Crato Formation (Lower Cretaceous)

ORYCTOS.Vol. 3 : 3 - 8. Décembre2000 FIRSTRECORD OT CALAMOPLEU RUS (ACTINOPTERYGII:HALECOMORPHI: AMIIDAE) FROMTHE CRATO FORMATION (LOWER CRETACEOUS) OF NORTH-EAST BRAZTL David M. MARTILL' and Paulo M. BRITO'z 'School of Earth, Environmentaland PhysicalSciences, University of Portsmouth,Portsmouth, POl 3QL UK. 2Departmentode Biologia Animal e Vegetal,Universidade do Estadode Rio de Janeiro, rua SâoFrancisco Xavier 524. Rio de Janeiro.Brazll. Abstract : A partial skeleton representsthe first occurrenceof the amiid (Actinopterygii: Halecomorphi: Amiidae) Calamopleurus from the Nova Olinda Member of the Crato Formation (Aptian) of north east Brazil. The new spe- cimen is further evidencethat the Crato Formation ichthyofauna is similar to that of the slightly younger Romualdo Member of the Santana Formation of the same sedimentary basin. The extended temporal range, ?Aptian to ?Cenomanian,for this genus rules out its usefulnessas a biostratigraphic indicator for the Araripe Basin. Key words: Amiidae, Calamopleurus,Early Cretaceous,Brazil Première mention de Calamopleurus (Actinopterygii: Halecomorphi: Amiidae) dans la Formation Crato (Crétacé inférieur), nord est du Brésil Résumé : la première mention dans le Membre Nova Olinda de la Formation Crato (Aptien ; nord-est du Brésil) de I'amiidé (Actinopterygii: Halecomorphi: Amiidae) Calamopleurus est basée sur la découverted'un squelettepar- tiel. Le nouveau spécimen est un élément supplémentaireindiquant que I'ichtyofaune de la Formation Crato est similaire à celle du Membre Romualdo de la Formation Santana, située dans le même bassin sédimentaire. L'extension temporelle de ce genre (?Aptien à ?Cénomanien)ne permet pas de le considérer comme un indicateur biostratigraphiquepour le bassin de l'Araripe. Mots clés : Amiidae, Calamopleurus, Crétacé inférieu4 Brésil INTRODUCTION Araripina and at Mina Pedra Branca, near Nova Olinda where cf. -

7.2.1. Introduction

Veldmeijer Cretaceous, toothed pterosaurs from Brazil. A reappraisal 1. Introduction Campos & Kellner (1985b) related that references to flying reptiles from Brazil (not from the Araripe Basin) were made as early as the 19th century, but the first find from Chapada do Araripe was described as late as the 1970s (Price, 1971, post–cranial remains of Araripesaurus castilhoi). Wellnhofer (1977) published the description of a phalanx of a wing finger of a pterosaur from the Santana Formation and named it Araripedactylus dehmi. Since then, much has been published on the pterosaurs from Brazil, and there has been an increasing interest in the material from this area, resulting in an increase in scientific interest in pterosaurs in general. The plateau of the Araripe Basin, in northeast Brazil on the boundaries of Piaui, Ceará and Pernambuco (figure 1.1) was already famous for its well preserved fossils, escpacially fish (e.g. Maisey, 1991), long before the area became the most important source of Cretaceous pterosaur fossils. At present, it is the most important area for Cretaceous pterosaurs globally, although an increasing number of finds are reported from China (e.g. Lü & Ji, 2005; Wang & Lü, 2001 and Wang & Zhou, 2003). Some of the Brazilian material is severely compacted (Crato Formatin; Frey & Martill, 1994; Frey et al., 2003a, b; Sayão & Kellner, 2000) and preserved on a laminated limestone comparable to that of Solnhofen. (The type locality of most, if not all, pterosaur fossils from the Araripe Basin is uncertain, because no systematic, scientically based excavations or even surveys have been done in this area. -

Late Jurassic Theropod Dinosaur Bones from the Langenberg Quarry

Late Jurassic theropod dinosaur bones from the Langenberg Quarry (Lower Saxony, Germany) provide evidence for several theropod lineages in the central European archipelago Serjoscha W. Evers1 and Oliver Wings2 1 Department of Geosciences, University of Fribourg, Fribourg, Switzerland 2 Zentralmagazin Naturwissenschaftlicher Sammlungen, Martin-Luther-Universität Halle-Wittenberg, Halle (Saale), Germany ABSTRACT Marine limestones and marls in the Langenberg Quarry provide unique insights into a Late Jurassic island ecosystem in central Europe. The beds yield a varied assemblage of terrestrial vertebrates including extremely rare bones of theropod from theropod dinosaurs, which we describe here for the first time. All of the theropod bones belong to relatively small individuals but represent a wide taxonomic range. The material comprises an allosauroid small pedal ungual and pedal phalanx, a ceratosaurian anterior chevron, a left fibula of a megalosauroid, and a distal caudal vertebra of a tetanuran. Additionally, a small pedal phalanx III-1 and the proximal part of a small right fibula can be assigned to indeterminate theropods. The ontogenetic stages of the material are currently unknown, although the assignment of some of the bones to juvenile individuals is plausible. The finds confirm the presence of several taxa of theropod dinosaurs in the archipelago and add to our growing understanding of theropod diversity and evolution during the Late Jurassic of Europe. Submitted 13 November 2019 Accepted 19 December 2019 Subjects Paleontology, -

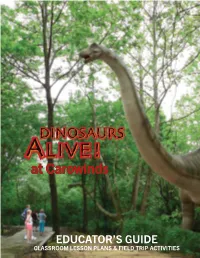

At Carowinds

at Carowinds EDUCATOR’S GUIDE CLASSROOM LESSON PLANS & FIELD TRIP ACTIVITIES Table of Contents at Carowinds Introduction The Field Trip ................................... 2 The Educator’s Guide ....................... 3 Field Trip Activity .................................. 4 Lesson Plans Lesson 1: Form and Function ........... 6 Lesson 2: Dinosaur Detectives ....... 10 Lesson 3: Mesozoic Math .............. 14 Lesson 4: Fossil Stories.................. 22 Games & Puzzles Crossword Puzzles ......................... 29 Logic Puzzles ................................. 32 Word Searches ............................... 37 Answer Keys ...................................... 39 Additional Resources © 2012 Dinosaurs Unearthed Recommended Reading ................. 44 All rights reserved. Except for educational fair use, no portion of this guide may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any Dinosaur Data ................................ 45 means—electronic, mechanical, photocopy, recording, or any other without Discovering Dinosaurs .................... 52 explicit prior permission from Dinosaurs Unearthed. Multiple copies may only be made by or for the teacher for class use. Glossary .............................................. 54 Content co-created by TurnKey Education, Inc. and Dinosaurs Unearthed, 2012 Standards www.turnkeyeducation.net www.dinosaursunearthed.com Curriculum Standards .................... 59 Introduction The Field Trip From the time of the first exhibition unveiled in 1854 at the Crystal -

The Geologic Time Scale Is the Eon

Exploring Geologic Time Poster Illustrated Teacher's Guide #35-1145 Paper #35-1146 Laminated Background Geologic Time Scale Basics The history of the Earth covers a vast expanse of time, so scientists divide it into smaller sections that are associ- ated with particular events that have occurred in the past.The approximate time range of each time span is shown on the poster.The largest time span of the geologic time scale is the eon. It is an indefinitely long period of time that contains at least two eras. Geologic time is divided into two eons.The more ancient eon is called the Precambrian, and the more recent is the Phanerozoic. Each eon is subdivided into smaller spans called eras.The Precambrian eon is divided from most ancient into the Hadean era, Archean era, and Proterozoic era. See Figure 1. Precambrian Eon Proterozoic Era 2500 - 550 million years ago Archaean Era 3800 - 2500 million years ago Hadean Era 4600 - 3800 million years ago Figure 1. Eras of the Precambrian Eon Single-celled and simple multicelled organisms first developed during the Precambrian eon. There are many fos- sils from this time because the sea-dwelling creatures were trapped in sediments and preserved. The Phanerozoic eon is subdivided into three eras – the Paleozoic era, Mesozoic era, and Cenozoic era. An era is often divided into several smaller time spans called periods. For example, the Paleozoic era is divided into the Cambrian, Ordovician, Silurian, Devonian, Carboniferous,and Permian periods. Paleozoic Era Permian Period 300 - 250 million years ago Carboniferous Period 350 - 300 million years ago Devonian Period 400 - 350 million years ago Silurian Period 450 - 400 million years ago Ordovician Period 500 - 450 million years ago Cambrian Period 550 - 500 million years ago Figure 2. -

A Revised Taxonomy of the Iguanodont Dinosaur Genera and Species

ARTICLE IN PRESS + MODEL Cretaceous Research xx (2007) 1e25 www.elsevier.com/locate/CretRes A revised taxonomy of the iguanodont dinosaur genera and species Gregory S. Paul 3109 North Calvert Station, Side Apartment, Baltimore, MD 21218-3807, USA Received 20 April 2006; accepted in revised form 27 April 2007 Abstract Criteria for designating dinosaur genera are inconsistent; some very similar species are highly split at the generic level, other anatomically disparate species are united at the same rank. Since the mid-1800s the classic genus Iguanodon has become a taxonomic grab-bag containing species spanning most of the Early Cretaceous of the northern hemisphere. Recently the genus was radically redesignated when the type was shifted from nondiagnostic English Valanginian teeth to a complete skull and skeleton of the heavily built, semi-quadrupedal I. bernissartensis from much younger Belgian sediments, even though the latter is very different in form from the gracile skeletal remains described by Mantell. Currently, iguanodont remains from Europe are usually assigned to either robust I. bernissartensis or gracile I. atherfieldensis, regardless of lo- cation or stage. A stratigraphic analysis is combined with a character census that shows the European iguanodonts are markedly more morpho- logically divergent than other dinosaur genera, and some appear phylogenetically more derived than others. Two new genera and a new species have been or are named for the gracile iguanodonts of the Wealden Supergroup; strongly bipedal Mantellisaurus atherfieldensis Paul (2006. Turning the old into the new: a separate genus for the gracile iguanodont from the Wealden of England. In: Carpenter, K. (Ed.), Horns and Beaks: Ceratopsian and Ornithopod Dinosaurs. -

Implications for Predatory Dinosaur Macroecology and Ontogeny in Later Late Cretaceous Asiamerica

Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences Theropod Guild Structure and the Tyrannosaurid Niche Assimilation Hypothesis: Implications for Predatory Dinosaur Macroecology and Ontogeny in later Late Cretaceous Asiamerica Journal: Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences Manuscript ID cjes-2020-0174.R1 Manuscript Type: Article Date Submitted by the 04-Jan-2021 Author: Complete List of Authors: Holtz, Thomas; University of Maryland at College Park, Department of Geology; NationalDraft Museum of Natural History, Department of Geology Keyword: Dinosaur, Ontogeny, Theropod, Paleocology, Mesozoic, Tyrannosauridae Is the invited manuscript for consideration in a Special Tribute to Dale Russell Issue? : © The Author(s) or their Institution(s) Page 1 of 91 Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences 1 Theropod Guild Structure and the Tyrannosaurid Niche Assimilation Hypothesis: 2 Implications for Predatory Dinosaur Macroecology and Ontogeny in later Late Cretaceous 3 Asiamerica 4 5 6 Thomas R. Holtz, Jr. 7 8 Department of Geology, University of Maryland, College Park, MD 20742 USA 9 Department of Paleobiology, National Museum of Natural History, Washington, DC 20013 USA 10 Email address: [email protected] 11 ORCID: 0000-0002-2906-4900 Draft 12 13 Thomas R. Holtz, Jr. 14 Department of Geology 15 8000 Regents Drive 16 University of Maryland 17 College Park, MD 20742 18 USA 19 Phone: 1-301-405-4084 20 Fax: 1-301-314-9661 21 Email address: [email protected] 22 23 1 © The Author(s) or their Institution(s) Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences Page 2 of 91 24 ABSTRACT 25 Well-sampled dinosaur communities from the Jurassic through the early Late Cretaceous show 26 greater taxonomic diversity among larger (>50kg) theropod taxa than communities of the 27 Campano-Maastrichtian, particularly to those of eastern/central Asia and Laramidia. -

Postcranial Skeletal Pneumaticity in Sauropods and Its

Postcranial Pneumaticity in Dinosaurs and the Origin of the Avian Lung by Mathew John Wedel B.S. (University of Oklahoma) 1997 A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Integrative Biology in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Kevin Padian, Co-chair Professor William Clemens, Co-chair Professor Marvalee Wake Professor David Wake Professor John Gerhart Spring 2007 1 The dissertation of Mathew John Wedel is approved: Co-chair Date Co-chair Date Date Date Date University of California, Berkeley Spring 2007 2 Postcranial Pneumaticity in Dinosaurs and the Origin of the Avian Lung © 2007 by Mathew John Wedel 3 Abstract Postcranial Pneumaticity in Dinosaurs and the Origin of the Avian Lung by Mathew John Wedel Doctor of Philosophy in Integrative Biology University of California, Berkeley Professor Kevin Padian, Co-chair Professor William Clemens, Co-chair Among extant vertebrates, postcranial skeletal pneumaticity is present only in birds. In birds, diverticula of the lungs and air sacs pneumatize specific regions of the postcranial skeleton. The relationships among pulmonary components and the regions of the skeleton that they pneumatize form the basis for inferences about the pulmonary anatomy of non-avian dinosaurs. Fossae, foramina and chambers in the postcranial skeletons of pterosaurs and saurischian dinosaurs are diagnostic for pneumaticity. In basal saurischians only the cervical skeleton is pneumatized. Pneumatization by cervical air sacs is the most consilient explanation for this pattern. In more derived sauropods and theropods pneumatization of the posterior dorsal, sacral, and caudal vertebrae indicates that abdominal air sacs were also present.