Wound Care Management: Tracheostomy and Gastrostomy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Patient Education Guide

Patient Education Guide Guidance and support to help you manage your gastrostomy tube (g-tube) Balloon ® Mini ONE Buttons The Leader in Enteral Device Innovation Contents Balloon Mini ONE® Button 2 How the Balloon Mini ONE® Button is Different 17 Decompression (Venting the 4 Balloon Mini ONE® Button Kit Contents Stomach / Releasing Gas) 18 G-Tube Related Concerns 6 Attaching Feed Sets 22 Stoma Site Related Concerns 8 Feeding with Your Mini ONE® Feeding Tube 23 Administering Medications 10 Stoma Site Care / Button Maintenance 24 Feeding Sets and Accessories 12 Replacing the Balloon Mini ONE® Button 25 Re-Ordering Information 16 Special Concerns for Children 1 Introduction to Tube Feeding Proper nutrition is essential to maintaining our bodies’ health, growth and ability to heal. Various medical conditions may make it difficult or impossible for a person to eat, and thus deny the body of essential nutrients. In such cases, a gastrostomy tube (g-tube) is inserted to provide direct access to the stomach for feeding. A g-tube is a convenient, comfortable and effective means for delivering nutritional formulas to the George J. Picha, body. These nutritional formulas are either commercially available or homemade using M.D., Ph.D., F.A.C.S. a food processor. A physician will prescribe the proper feeding procedure, formula Founder of AMT and Co-inventor of the and amount of water to most effectively feed each patient. first Button low profile feeding device. Comfort and Confidence are Important, Too AMT specializes in enteral devices, our As a caregiver or patient, we believe you have a right to the most comfortable core business. -

Content Production and Management by Applying Artificial Intelligence Techniques for Content Composition, Representation (Format) and Workflow; Ii

IST-2-511299 Automating Production of Cross Media Content for Multi-channel Distribution www.AXMEDIS.org CCoonntteenntt PPrroodduuccttiioonn Version: 1.0 URL: http://www.axmedis.org/ David Luigi FUSCHI GIUNTI Interactive Labs Laurence PEARCE XIM AXMEDIS: Automating Production of Cross Media Content for Multi-channel Distribution www.AXMEDIS.org 1 Preface Digital-content market is urging better pricing and value-for-money for industry products and services. This is clearly evident in the recent price reductions by major companies in the sector. The containment of sale prices is a vital key when setting up a viable and sustainable business venture in the digital cross media content. Possible solutions to this challenge could be found by automating, accelerating and re- structuring production processes, and providing solution to the content protection. Such solutions will en- able the production processes to be faster and cheaper, while at the same time providing new capabilities to support safer distribution. AXMEDIS aims to meet the challenges of market demand by: i. reducing costs for content production and management by applying Artificial Intelligence techniques for content composition, representation (format) and workflow; ii. reducing distribution and aggregation costs in order to increase accessibility with a Peer-to-Peer (P2P) platform at Business-to-Business (B2B) level, which can integrate content management sys- tems and workflows; iii. providing new methods and tools for innovative and flexible Digital Rights Management (DRM), -

CQ-TV Is Produced on an ATARI MEGA ST4 Computer System, Using the PROTEXT Word Processing Package and the TIMEWORKS Desktop Publishing Package

EQINIU No. 156 NOVEMBER 1991 BRITISH AMATEUR TELEVISION CLUB GUESS WHAT ? CONTENTS 7 SATELLITE TV NEWS Trevor Brown G8CJS 9 S-VHS/CVBS TO RGB CONVERTER H.Reelen 20 PULSAR - DIGITAL CIRCUIT SIMULATOR Mike Wooding G6IQM SOFTWARE PACKAGE REVIEW 25 CONSTRUCTING AERIAL PHASING LINES Ron Neyens NOCIH 26 MORE CROPREDY BOARD TIPS Brian Kelly GW6BWX 28 A NEW SSTV STANDARD ? Mike Wooding G6IQM 31 CONTEST CALENDAR 32 A 5-ELEMENT VIDEO FILTER John Cronk GW3MEO 33 IN THE STUDIO PART-13 John Goode 40 USING OSCILLOSCOPES Part-9 (Conclusion) Mike Wooding G6IQM SUP-1 to SUP-8 PUBLICATIONS AND MEMBERS' SERVICES SUPPLEMENT 45 THE DAYTON HAMFEST REPORT Andy Emmerson G8PTH 48 A DETACHABLE HIGH POWER E-PLANE PROBE Dr.J.A.Share Msc. Phd. 50 BEYOND TTL Part-1 Trevor Brown G8CJS 56 10GHZ AN THE EASY WAY Part-4 Jim Toon GOFNH 59 FEEDBACK - THE TDA3590 AGAIN Tom Mitchell G3LMX 62 BROADCAST BAND DX-TV RECEPTION Garry Smith & Keith Hamer 67 CONTEST NEWS Bob Platts G8OZP 68 NON THE AIR Andy Emmerson G8PTH 71 HOW TO GET INTO SAT N - WITH A MELON INSTEAD OF A DISH ! REVIEW Andy Emmerson G8PTH 73 THE BATC AT THE HAMFEST Brian Summers G8GQS 75 REPEATER GROUP AFFILLIATIONS 76 THE BATC BULLETIN BOARD SYSTEM 77 MORE ON THATVIDEO FILTER Peter Grannell G4TQB CLOSE FOR PRESS FOR THE NEXT ISSUE 20th DECEMBER 1991 CQ-TV is produced on an ATARI MEGA ST4 computer system, using the PROTEXT word processing package and the TIMEWORKS desktop publishing package. The camera- ready artwork is produced on an NEC PINWRITER P2200 24-pin dot-matrix printer. -

Spectrophotometric Determination of Thorium with the Trisodium Salt of 2-(2-Hydroxy-3,6-Disulfo-1-Naphthylazo)

Ames Laboratory ISC Technical Reports Ames Laboratory 6-1953 Spectrophotometric determination of thorium with the trisodium salt of 2-(2-hydroxy-3,6-disulfo-1-naphthylazo)- benzenearsonic acid and some properties of complexes involved Carol H. Byrd Iowa State College Charles V. Banks Iowa State College Follow this and additional works at: http://lib.dr.iastate.edu/ameslab_iscreports Part of the Chemistry Commons Recommended Citation Byrd, Carol H. and Banks, Charles V., "Spectrophotometric determination of thorium with the trisodium salt of 2-(2-hydroxy-3,6-disulfo-1-naphthylazo)-benzenearsonic acid and some properties of complexes involved" (1953). Ames Laboratory ISC Technical Reports. 62. http://lib.dr.iastate.edu/ameslab_iscreports/62 This Report is brought to you for free and open access by the Ames Laboratory at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Ames Laboratory ISC Technical Reports by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Spectrophotometric determination of thorium with the trisodium salt of 2-(2-hydroxy-3,6-disulfo-1-naphthylazo)-benzenearsonic acid and some properties of complexes involved Abstract The ods ium salt of 2-(2-hydroxy-3 3 6-disulfo-1- naphthylazo)-benzenearsonic acid, hereinafter referred to as thorin, has been extensively employed as a reagent for the spectrophotometric determination of thorium in recent years. No studies of the nature of the reaction between thorin and thorium have been reported. In this work, an examination of some properties of the complexes involved has been initiated. Keywords Ames Laboratory Disciplines Chemistry This report is available at Iowa State University Digital Repository: http://lib.dr.iastate.edu/ameslab_iscreports/62 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page I. -

Minionelow Profile Balloon G-Tube Patient Education Guide

Innovating. Educating. Changing Lives.™ ® MiniONELow Profile Balloon G-Tube Patient Education Guide Guidance & support to help you manage your gastrostomy tube (G-tube) Patient Education Guide Contents Introduction to Tube Feeding ® MiniONE Balloon Button Patient Education Guide Proper nutrition is essential to maintaining our bodies’ health, growth, and ability to heal. Introduction to Tube Feeding 1-3 Various medical conditions may make it difficult or impossible for a person to eat, and thus deny the body of essential nutrients. In such cases, a gastrostomy tube (G-tube) may be Enteral Nutrition 4-5 inserted to provide direct access to the stomach for feeding. A G-tube is a convenient, How the MiniONE® is Different 6-9 comfortable and effective means for delivering nutritional formulas to the body. These Attaching Feed Sets to the MiniONE® Balloon Button 10-11 nutritional formulas are either commercially available or homemade using a food processor. ® A healthcare provider will prescribe the proper feeding procedure, formula, and amount of Feeding With Your MiniONE 12-13 water to most effectively feed each patient. MiniONE® Maintenance 14-15 Replacing the MiniONE® Balloon Button 16-19 Comfort and Confidence are Important, Too As a caregiver or patient, we believe you have a right to the most comfortable and reliable Administering Medications 20 gastrostomy tubes, that’s why we developed the MiniONE® Balloon Button. Reading and Special Concerns For Children 21 understanding this guide, along with using our products, will help you achieve the comfort Device Related Concerns 22-25 and confidence you deserve. Stoma Site Related Concerns 26 Decompression 27 Compatible Feed Sets 28 Feed Set Accessories 29 Legacy Balloon Button Kit 30 MiniONE® Family 31 Re-Ordering information 32-33 Information Card 34-35 Share Your Story 36 Social Media 37 Customer Service 38 George J. -

Type & Typography

Type & Typography by Walton Mendelson 2017 One-Off Press Copyright © 2009-2017 Walton Mendelson All rights reserved. [email protected] All images in this book are copyrighted by their respective authors. PhotoShop, Illustrator, and Acrobat are registered trademarks of Adobe. CreateSpace is a registered trademark of Amazon. All trademarks, these and any others mentioned in the text are the property of their respective owners. This book and One- Off Press are independent of any product, vendor, company, or person mentioned in this book. No product, company, or person mentioned or quoted in this book has in any way, either explicitly or implicitly endorsed, authorized or sponsored this book. The opinions expressed are the author’s. Type & Typography Type is the lifeblood of books. While there is no reason that you can’t format your book without any knowledge of type, typography—the art, craft, and technique of composing and printing with type—lets you transform your manuscript into a professional looking book. As with writing, every book has its own issues that you have to discover as you design and format it. These pages cannot answer every question, but they can show you how to assess the problems and understand the tools you have to get things right. “Typography is what language looks like,” Ellen Lupton. Homage to Hermann Zapf 3 4 Type and Typography Type styles and Letter Spacing: The parts of a glyph have names, the most important distinctions are between serif/sans serif, and roman/italic. Normal letter spacing is subtly adjusted to avoid typographical problems, such as widows and rivers; open, touching, or expanded are most often used in display matter. -

Looking at Shirley, the Ultimate Norm: Colour Balance, Image Technologies, and Cognitive Equity

Looking at Shirley, the Ultimate Norm: Colour Balance, Image Technologies, and Cognitive Equity Lorna Roth Concordia University Abstract: Until recently, due to a light-skin bias embedded in colour film stock emulsions and digital camera design, the rendering of non-Caucasian skin tones was highly deficient and required the development of compensatory practices and technology improvements to redress its shortcomings. Using the emblem- atic “Shirley” norm reference card as a central metaphor reflecting the changing state of race relations/aesthetics, this essay analytically traces the colour adjust- ment processes in the industries of visual representation and identifies some pro- totypical changes in the field. The author contextualizes the history of these changes using three theoretical categories: the ‘technological unconscious’ (Vaccari, 1981), ‘dysconsciousness’ (King, 2001), and an original concept of ‘cognitive equity,’ which is proposed as an intelligent strategy for creating and promoting equity by inscribing a wider dynamic range of skin tones into image technologies, products, and emergent practices in the visual industries. Keywords: Colour balance; Norm reference cards; Dynamic range; Technological unconscious; Dysconsciousness; Cognitive equity; Cultural studies Résumé : Jusqu’à récemment, en raison d’un préjugé favorisant la peau claire dans les films couleurs et dans la conception des caméras numériques, la reproduction des couleurs de peaux non-caucasiennes a été très déficiente, exigeant le développement de diverses techniques de compensation et d’amélioration. Utilisant la carte de référence normative « Shirley » comme métaphore pour refléter l'évolution des rapports entre les races et leurs pratiques esthétiques, cet essai analyse les processus d’ajustement de la couleur dans les industries de la représentation visuelle et identifie certains prototypes de changements dans le domaine. -

Chemical Hygiene Plan Ii Revised 03/2021 Table of Contents

MAR 2021 Office of Environmental Health and Safety Principal Author/Editor: David Webber, PhD/Chemical Hygiene Officer Contributing Authors/Editors: Nikolai Evdokimov, PhD, James Gibson, PhD, Tania Guardado, PhD, Amanda Jevons, Deona Willes, MPH Graphics/Design: Alfred M. Bouziane, MS, Brent Pantell USC Chemical Hygiene Plan ii Revised 03/2021 Table of Contents i.0 2021 Revision Summary Section 3.0 vi Section 4.0 vi Section 5.0 vii Section 7.0 vii Section 8.0 viii Section 10.0 x Appendix D x Appendix G x 1.0 Introduction Purpose and Scope 1.1 Sources of Safety Information 1.2 2.0 Regulatory Requirements 3.0 Roles and Responsibilities Research Safety Oversight Committee (RSOC) 3.1 Campus-Wide Chemical Safety Committee (CCSC) 3.1 Other Safety Committees 3.2 Office of Environmental Health & Safety 3.2 Principal Investigator (PI) 3.3 Training Requirements 3.5 4.0 Basics of Laboratory Safety Hazard, Risk, and Safety Management 4.1 Hierarchy of Safety Controls 4.1 Group Safety Management and Safety Culture 4.4 USC Chemical Hygiene Plan iii Revised 03/2021 Basics of Lab Facilities, Equipment, and Emergency Supplies 4.7 Emergency Equipment and Supplies 4.15 Open Flames 4.20 5.0 Hazard Communication Labeling and Signage Systems 5.2 Labelling and Signage in the Lab: What You Need to Do 5.5 Safety Data Sheets (SDSs): What Are They? 5.7 SDSs in The Lab: What You Need to Do 5.8 6.0 Hazardous Chemicals and Hazard Classification Introduction 6.1 Health-Hazardous Chemicals: Routes of Exposure 6.2 Particularly Hazardous Substances (PHS) 6.16 7.0 Chemical -

Download Doc ^ Test Card F (Paperback)

ZXEBSPG53KL3 > eBook / Test Card F (Paperback) Test Card F (Paperback) Filesize: 4.59 MB Reviews Thorough information for publication lovers. it was actually writtern extremely properly and useful. I found out this publication from my i and dad suggested this book to learn. (Dr. Garnett McLaughlin II) DISCLAIMER | DMCA WNU9F4OMDEHA ^ PDF » Test Card F (Paperback) TEST CARD F (PAPERBACK) AK Press, United Kingdom, 2001. Paperback. Condition: New. Language: English . Brand New Book. Test Card F is a graphic demolition derby through the culture of a factory farmed and show-shocked society, a society whose sell-by date has long since expired. Using savage image/text cut and paste, this controversial book explodes all previous media theories and riots through the Global Village, looting the ideological supermarkets of all its products: anti-fascism, Malcolm X, James Bulger, the Gulf War, Satanic Abuse, Somalia, and Eastern Europe. Test Card F joyrides in front of the surveillance cameras, amidst the rubble of a junkyard nation, and heaves television s burnt-out carcass through the plate glass shop window of independent video and community access broadcasting. It transcends postmodern and Situationist analysis in its positive refusal of the concept of Truth. Test Card F has no named authors; it originates in the pirate transmissions of the unruly squatters of cyberspace when scheduled programming closes down for the night. Read Test Card F (Paperback) Online Download PDF Test Card F (Paperback) VTQTLAWF6LL9 ~ Kindle / Test Card F (Paperback) Oth er PDFs Let's Find Out!: Building Content Knowledge With Young Children Stenhouse Publishers. Paperback. Book Condition: new. -

A Clinician's Guide: Caring for People with Gastrostomy Tubes and Devices

A Clinician’s Guide: Caring for people with gastrostomy tubes and devices From pre-insertion to ongoing care and removal AGENCY FOR CLINICAL INNOVATION GASTROENTEROLOGICAL NURSES COLLEGE OF AUSTRALIA (GENCA) Level 4, Sage Building PO Box 7345 67 Albert Avenue Beaumaris VIC 3193 Chatswood NSW 2067 Australia PO Box 699 T +61 1300 788 155 | F +61 1300 799 439 Chatswood NSW 2057 E [email protected] | www.genca.org T +61 2 9464 4666 | F +61 2 9464 4728 E [email protected] | www.aci.health.nsw.gov.au Produced by: The Agency for Clinical Innovation and the Gastroenterological Nurses College of Australia SHPN: (ACI) 140453 ISBN: 978-1-76000-112-4 Electronic copies of this publication can be obtained from: ACI website: www.aci.health.nsw.gov.au GENCA website: www.genca.org Disclaimer: Content within this publication was accurate at the time of publication. This work is copyright. It may be reproduced in whole or part for study or training purposes subject to the inclusion of an acknowledgment of the source. Photographs included in this document are owned by the clinicians who provided them. They are not to be copied or reproduced. This document may not be reproduced for commercial usage or sale. Reproduction for purposes other than those indicated above requires written permission from the ACI and GENCA. © Agency for Clinical Innovation 2014 Version 1.2: March 2015 The ACI will undertake a review of the document within 2-5 years of its release and will liaise with relevant stakeholders during the revision process. -

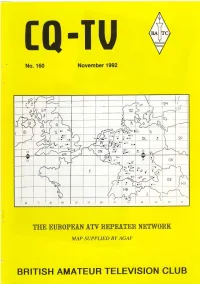

CQ-TV Is Produced on a 386 PC Computer System, Using the PROTEXT Wor D Processing Package and the TIMEWORKS Desktop Publishing Package

CQ-T V No. 160 November 1992 I ' f (' o u V dm, OZ ire. a V C , slA,9 El L~~ AiH .HV M H NH_ S AiV• fi D L P - .221 0 .6 PI X, 3 ID ON N3, a o 4 `LN LX • 6 r JN O K ~3r R 2 X20 F %1 FMS •FTV 0E ~ 60 80 90 00 10 20 3.. 4o so 70 _ PEAN ATV EATE ifs NETTW r K MAP SUPPLIED BY AGA F BRITISH AMATEUR TELEVISION CLU B The BATC at the Dagenham Town Show circa 1958/5 9 Courtesy of Ted Stiles GOBHT CONTENTS 9 A Synclock Unit for the BBC Home Computer Hans Wessels PA2HW G 17 Lighting AT V Norman Ash G7AS H 21 A NICAM Decode r Rob Krijgsman PEICH Y 34 Digitalkers Revisited Steve Pocock GOCPV 36 Fade to Black, with A/B Mixer Peter Carliell 38 Tidal Propogation D .J.Bradford G8KB C 41 70cm TVI Filte r John Stockley G8MNY 42 The Middlesex Sho w John Stockley G8MNY 43 Camtech TXV4000 PLL Video Transmitter Review Mike Wooding G6IQM 51 Beyond TT L Trevor Brown G8CJS 56 BSB on 3cm ! ! Bob Platts G8OZ P 58 More on BSB Receivers Trevor Brown G8CJS 59 13cm ATV - It's as easy as this ! ! Bob Plattes GSOZ P 64 Expanding the Pace SS6000 Satellite Receiver Trevor Brown G8CJ S 66 Satellite TV News Paul Holland G3TZ O 73 BATC Contest Championship League Tabl e 74 Contest New s Richard Guttridge G4YT V 76 Contest Calendar 77 TV on the Air Andy Emmerson G8PT H 84 SSTV - A New British Scan Convertor in Kit Form Review Roland Humphries G4UKL CLOSE FOR PRESS FOR THE NEXT ISSUE 20th DECEMBER 1992 CQ-TV is produced on a 386 PC computer system, using the PROTEXT wor d processing package and the TIMEWORKS desktop publishing package . -

A Test of Photovoice and the Zaltman Metaphor

TEST PATTERN: A TEST OF PHOTOVOICE AND THE ZALTMAN METAPHOR ELICITATION TECHNIQUE AND A SEARCH FOR PATTERNS IN LANDSCAPE ENCLOSURE PREFERENCES by KATHERINE LINCOURT (Under the Direction of KATHERINE MELCHER) ABSTRACT Landscape architects may be able to improve communication with clients and community members and generate better data for research and design projects by changing the way they use the images and photographs generated by others. This thesis explores two methods that rely on images generated by and interpreted by study participants: Photovoice and the Zaltman Metaphor Elicitation Technique (ZMET). To test the methods a problem was generated from Christopher Alexander et al.’s (1977) Pattern Language and nine study participants were evenly divided into three arms (ZMET, Photovoice, and a control group using language-based interviewing) and asked about their perceptions and preferences for ‘gardens’ and ‘enclosure’ (Pattern 173 – Garden Wall). The interviews were coded to create themes, which are discussed relative to Pattern 173 and the design of enclosed garden spaces. Additional information is provided on my experience with the methods, the impact of changes to the methods, participants’ responses to the study arms, and suggestions for researchers. Implications for landscape architecture and potential future applications for the methods are discussed. INDEX WORDS: Landscape Architecture, Zaltman, ZMET, Consumer Research, Subconscious, Values, Photovoice, Participatory Research, Photography, Interviews, Pattern Language, Enclosure