THE CASE of DOMINICA's AMERINDIANS Robert A. Myers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Political Change in Dominica, the Commonwealth West Indies. Cuthbert J

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 1-1-1973 From crown colony to associate statehood : political change in Dominica, the Commonwealth West Indies. Cuthbert J. Thomas University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1 Recommended Citation Thomas, Cuthbert J., "From crown colony to associate statehood : political change in Dominica, the Commonwealth West Indies." (1973). Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014. 1879. https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1/1879 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ^^^^^^^ ^0 ASSOCIATE STATEHOOD: CHANGE POLITICAL IN DOMINICA, THE COMMONWEALTH WEST INDIES A Dissertation Presented By CUTHBERT J. THOMAS Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 1973 Major Subject Political Science C\ithbert J. Thomas 1973 All Rights Reserved FROM CROV/N COLONY TO ASSOCIATE STATEHOOD: POLITICAL CHANGE IN DOMINICA, THE COMMONWEALTH WEST INDIES A Dissertation By CUTHBERT J. THOMAS Approved as to stylq and content by; Dr. Harvey "T. Kline (Chairman of Committee) Dr. Glen Gorden (Head of Department) Dr» Gerard Braunthal^ (Member) C 1 Dro George E. Urch (Member) May 1973 To the Youth of Dominica who wi3.1 replace these colonials before long PREFACE My interest in Comparative Government dates back to ray days at McMaster University during the 1969-1970 academic year. -

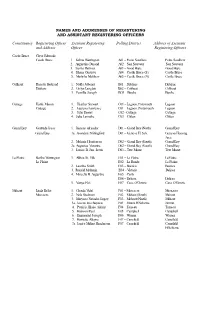

Names and Addresses of Registering and Assistant Registering Officers

NAMES AND ADDRESSES OF REGISTERING AND ASSISTANT REGISTERING OFFICERS Constituency Registering Officer Assistant Registering Polling District Address of Assistant and Address Officer Registering Officers Castle Bruce Cleve Edwards Castle Bruce 1. Kelma Warrington A01 – Petite Soufriere Petite Soufriere 2. Augustina Durand A02 – San Sauveur San Sauveur 3. Sasha Darroux A03 – Good Hope Good Hope 4. Shana Gustave A04 – Castle Bruce (S) Castle Bruce 5. Marlisha Matthew A05 – Castle Bruce (N) Castle Bruce Colihaut Rosette Bertrand 1. Nalda Jubenot B01 – Dublanc Dublanc Dublanc 2. Gislyn Langlais B02 – Colihaut Colihaut 3. Fernillia Joseph BO3 – Bioche Bioche Cottage Hartie Mason 1. Heather Stewart C01 – Lagoon, Portsmouth Lagoon Cottage 2. Laurena Lawrence C01 – Lagoon ,Portsmouth Lagoon 3. Julie Daniel C02 - Cottage Cottage 4. Julia Lamothe C03 – Clifton Clifton Grand Bay Gertrude Isaac 1. Ireneus Alcendor D01 – Grand Bay (North) Grand Bay Grand Bay 1a. Avondale Shillingford D01 – Geneva H. Sch. Geneva Housing Area 2. Melanie Henderson D02 – Grand Bay (South) Grand Bay 2a. Augustus Victorine D02 – Grand Bay (South) Grand Bay 3. Louise B. Jno. Lewis D03 – Tete Morne Tete Morne La Plaine Bertha Warrington 1. Althea St. Ville E01 – La Plaine LaPlaine La Plaine E02 – La Ronde La Plaine 2. Laurina Smith E03 – Boetica Boetica 3. Ronald Mathurin E04 - Victoria Delices 4. Marcella B. Augustine E05 – Carib E06 – Delices Delices 5. Vanya Eloi E07 – Case O’Gowrie Case O’Gowrie Mahaut Linda Bellot 1. Glenda Vidal F01 – Massacre Massacre Massacre 2. Nola Stedman F02 – Mahaut (South) Mahaut 3. Maryana Natasha Lugay F03- Mahaut (North) Mahaut 3a. Josette Jno Baptiste F03 – Jimmit H/Scheme Jimmit 4. -

FP HF SLDHF2 St Lucia 2E Cover.Indd

Footprint St Lucia & Dominica n Extensive coverage of the most famous and lesser-known sites, from the forested mountains of St Lucia to the marine parks of Dominica. Also includes Fort-de-France in Martinque. & Lucia Dominica St 1 W I I n Expert author S N Sarah Cameron has L D A W N travelled throughout the Caribbean for DOMINICA A D R S MARTINIQUE D over two decades ST LUCIA n Inspirational colour section and detailed maps to help you plan your trip n Authoritative advice and recommendations to ensure you find the best accommodation, restaurant or tour operator n Comprehensive information to immerse you in St Lucia’s colonial history and Dominica’s traditional culture n Footprint have built on years of experience to become the experts on the Caribbean ‘Footprint is the best – engagingly written, comprehensive, honest and bang on the ball.’ THE SUNDAY TIMES Footprint Handbook Travel: Caribbean UK £7.99 2nd edition USA $12.99 St Lucia & ISBN 978 1 910120 56 9 Dominica footprinttravelguides.com SARAH CAMERON Planning your trip. .2 St Lucia . 30 Castries. 31 North of Castries . 39 Rodney Bay. 40 Pigeon Island . 42 North coast . 43 East coast to Vieux Fort . 44 Vieux Fort . 48 West coast to Soufrière . 48 Soufrière . 50 South of Soufrière. 51 The southwest . 56 Listings. 58 Martinique Fort-de-France . 80 Dominica . 86 Roseau . 87 Trafalgar Falls. 91 Morne Trois Pitons National Park . 92 South coast. 94 Leeward coast . 95 The north. 98 Transinsular road. 98 Atlantic coast . 99 Listings. .101 Background . 116 Practicalities . 130 Index . -

Population and Housing Census 2011 (Preliminary Results)

Commonwealth of Dominica 2011 POPULATION AND HOUSING CENSUS PRELIMINARY RESULTS CENTRAL STATISTICAL OFFICE MINISTRY OF FINANCE KENNEDY AVENUE ROSEAU SEPTEMBER 2011 CENSUS 2011 - Preliminary Results Table of Contents Page Introduction 3 Explanatory Notes 4 Review 6 Table 1 Review of Demographic Data 1991 to 2010 9 Table 2 Population Trends - Census 1871 to 2011 9 Table 3 Population and Sex Ratio by Parish- 2011 10 Table 4 Non-institutional Population and Percentage Change by Parish - Censuses 1981 - 2011 11 Table 5 Non-institutional Population Distribution and Density by Parish Censuses 1991 - 2011 12 Table 6 Non-institutional and Institutional Population by Parish - 2011 13 " Table 7 Non-institutional Population by Geographic Area 1991- 2011 14 Table 8 Non-institutional Population, Households and Dwelling Units by Geographic Area. 19 Table 9 Non-institutional Population, Households and Type of Dwelling Units by Geographic Area. 23 Table 9.1 Non-institutional Population, Households and Dwelling Units 26 Chart 1 Non-Institutional Population Census 1871-Census -2011 27 Chart 2 Non-Institutional Population by sex and Census years 1981-2011 27 2 CENSUS 2011 - Preliminary Results INTRODUCTION The preliminary results of Census 2011 was extracted from the Census Visitation Records. It must therefore be emphasized that this information is based on preliminary findings from the May 2011 Dominica Population and Housing Census. It is not final information and is subject to slight changes after processing of final Census data. This report also includes census data from 1981 and other demographic trends over the last ten years. The Central Statistical Office acknowledges the assistance and cooperation of individuals groups, institutions, and government departments in making this Census successful. -

Heritage Education — Memories of the Past in the Present Caribbean Social Studies Curriculum: a View from Teacher Practice Issue Date: 2019-05-28

Cover Page The handle http://hdl.handle.net/1887/73692 holds various files of this Leiden University dissertation. Author: Con Aguilar E.O. Title: Heritage education — Memories of the past in the present Caribbean social studies curriculum: a view from teacher practice Issue Date: 2019-05-28 Chapter 6: The presence of Wai’tu Kubuli in teaching history and heritage in Dominica 6.1 Introduction Figure 6.1: Workshop at the Salybia Primary School Kalinago Territory, Dominica, January 2016. During my stay in Dominica, I had the opportunity to organize a teachers’ workshop with the assistance of the indigenous people of the Kalinago Territory. Although the teachers interact with Kalinago culture on a daily basis, we decided to explore the teachers’ knowledge of indigenous heritage and to challenge them in activities where they could put their knowledge into practice. We then drew animals, plants, tools and objects that are found in daily life in the Kalinago Territory. Later on in the workshop, we asked teachers about the Kalinago names that were printed on their tag names. Teachers were able to recognize some of these Kalinago names, and sometimes even the stories behind them. In this simple way, we started our workshop on indigenous history and heritage — because sometimes the most useful and meaningful learning resources are the ones we can find in our everyday life. This case study took place in Dominica; the island is also known by its Kalinago name, Wai’tu Kubuli, which means “tall is her body.” The Kalinago Territory is the home of the Kalinago people. -

Sales Manual

DominicaSALES MANUAL 1 www.DiscoverDominica.com ContentsINTRODUCTION LAND ACTIVITES 16 Biking / Dining GENERAL INFORMATION 29 Hiking and Adventure / 3 At a Glance Nightlife 4 The History 30 Shopping / Spa 4 Getting Here 31 Turtle Watching 6 Visitor Information LisT OF SERviCE PROviDERS RICH HERITAGE & CULTURE 21 Tour Operators from UK 8 Major Festivals & Special Events 22 Tour Operators from Germany 24 Local Ground Handlers / MAIN ACTIVITIES Operators 10 Roseau – Capital 25 Accommodation 18 The Roseau Valley 25 Car Rentals & Airlines 20 South & South-West 26 Water Sports 21 South-East Coast 2 22 Carib Territory & Central Forest Reserve 23 Morne Trois Pitons National Park & Heritage Site 25 North-East & North Coast Introduction Dominica (pronounced Dom-in-ee-ka) is an independent nation, and a member of the British Commonwealth. The island is known officially as the Commonwealth of Dominica. This Sales Manual is a compilation of information on vital aspects of the tourism slopes at night to the coastline at midday. industry in the Nature Island of Dominica. Dominica’s rainfall patterns vary as well, It is intended for use by professionals and depending on where one is on the island. others involved in the business of selling Rainfall in the interior can be as high as Dominica in the market place. 300 inches per year with the wettest months being July to November, and the As we continue our partnership with you, driest February to May. our cherished partners, please help us in our efforts to make Dominica more well known Time Zone among your clients and those wanting Atlantic Standard Time Zone, one hour information on our beautiful island. -

Population and Housing Census 2001

._ ...•..__...__._-------- • COMMONWEALTH OF DOMINICA POPULATION AND HOUSING CENSUS -2001 Preliminary Results CENTRAL STATISTICAL OFFICE MINISTRY OF FINANCE AND PLANNING KENNEDY AVENUE ROSEAU AUGUST 2001 • Census 2001 - Preliminary Tables TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Introduction 2 Explanatory Notes 3-4 A Review of the Census Data 5-8 Table 1: Total Population and Sex Ratio by Parish 9 Table 2: Non-institutional Population and Population Change by Parish, - Censuses 1981 - 2001 10 Table 3: Non-institutional Population, Distribution and Density by Parish Censuses 1981 - 2001 11 Table 4: Non-institutional/Institutional Population by Parish 12 Table 5: Non-institutional Population by Geographical Area 1981 - 2001 13 - 15 Table 6: Non-institutional Population, Households and Dwelling Units by Geographical Area. 16 - 18 Table 7: Non-institutional Population, Households and Type of Dwelling Units by Geographical Area. 19 - 21 CENSUS 2001 - Preliminary Results Introduction The preliminary results of Census 2001 was extracted from the Census Visitation Records. It must therefore be emphasized that this information is based on preliminary findings from the May 2001 Dominica Population Census. It is not final information and is sUbject to slight changes after processing of final Census data. This report also includes census data from 1981 and other demographic trends over the last ten years. The Central Statistical Office acknowledges the assistance and cooperation of individuals groups, institutions, and government departments in making this Census successful. Much appreciation and thanks are extended to Permanent Secretaries, Heads of Government Departments, the Private Sector, The Government Information Service, media houses, religious leaders, local government offices, the Cable and Wireless Company, Census Advisor, Census Area Supervisors and Census Enumerators and many others who contributed in any way towards this national exercise. -

Multi-Hazard Early Warning Systems Gaps Report: Dominica, 2018

MULTI-HAZARD EARLY WARNING SYSTEMS GAPS ASSESSMENT REPORT FOR THE COMMONWEALTH OF DOMINICA, 2018 MULTI-HAZARD EARLY WARNING SYSTEMS GAPS REPORT: DOMINICA, 2018 Led by Dominica Emergency Management Organisation Director Mr. Fitzroy Pascal Author Gelina Fontaine (Local Consultant) National coordination John Walcott (UNDP Barbados & OECS) Marlon Clarke (UNDP Barbados & OECS) Regional coordination Janire Zulaika (UNDP – LAC) Art and design: Beatriz H.Perdiguero - Estudio Varsovia This document covers humanitarian aid activities implemented with the financial assistance of the European Union. The views expressed herein should not be taken, in any way, to reflect the official opinion of the European Union, and the European Commission is not responsible for any use that may be made of the information it contains. UNDP CDEMA IFRC ECHO United Nations Caribbean Disaster International Federation European Civil Protection Development Emergency of the Red Cross and and Humanitarian Programme Management Agency Red Crescent Societies Aid Operations Map of Dominica. (Source Jan M. Lindsay, Alan L. Smith M. John Roobol and Mark V. Stasiuk Dominica, Chapter for Volcanic Hazards Atlas) CONTENTS 1. Executive Summary 2 2. Dominica Context 6 3. MHEWS Capacity and Assets 16 4. MHEWS Specific Gaps As It Relates To International Standards 24 27 4.1 Disaster Risk Knowledge Gaps DOMINICA OF 4.2 Disaster Risk Knowledge Recommendations 30 4.3 Gaps in detection, monitoring, analysis and forecasting 31 4.4 Recommendations for detection, monitoring, analysis and forecasting 35 4.5 Warning Dissemination and Communication Gaps 36 4.6 Recommendations for Warning Dissemination and Communication 38 4.7 Gaps in Preparedness and Response Capabilities 39 4.8 Recommendations for Preparedness and Response Capabilities 14 5. -

Mapaction Brochure

Potable water status: Litres delivered in last five days and remaining days supplies Up to 8 October 2017 Potable Water status: litres delivered in last 5 days and remaining days supplies (up to 08 Oct 2017) All settlements within an 'Operational' Water Dominica 0 2.5 5 10 15 MA626 v1 Capuchin Penville Capuchin Service Area are removed from this representation L'Autre Clifton Bord Kilometers as their demands 'should' be being met. In 2017, Hurricanes Cottage & Cocoyer Vieille !( Settlements Calculation of water remaining based on the Toucari & Morne Cabrit Case population x 7.5 litres per person per day Irma and Maria Savanne Paille Savanne Paille & Tantan & Tantan Moore Park Thibaud Major/Minor Road Thibaud devastated parts of Estate Moore Park Estate Calibishie Anse de Mai Bense Parish Boundaries Bense & Hampstead the Caribbean. Dos & Hampstead Woodford Dos D'Ane Lagon & De D'Ane Hill Woodford Hill La Rosine Borne Borne MapAction Portsmouth Glanvillia Wesley Wesley ST. JOHN responded quickly ST. JOHN Picard 6561 PPL and in numbers, 6561 PPL ST. ANDREW ST. ANDREW producing hundreds Marigot & 9471 PPL 9471 PPL Marigot & Concord of maps, including Concord this one showing the Atkinson Dublanc & Bataka Dublanc Atkinson & Bataka urgent need for water Bioche ST. PETER Bataka Bioche Bataka in Dominica, which 1430 PPL Water (Days) ST. PETER 1430 PPL Salybia & St. Cyr & Gaulette & Sineku took a direct hit from St. Cyr Remaining days St. Cyr Colihaut Colihaut Category 5 Hurricane Gaulette (! < 1 day Gaulette Maria. MapAction Sineku (! 1 - 2 days Sineku volunteers were Coulibistrie Coulibistrie (! 2 - 3 days Morne Rachette amongst the first ST. -

Demographic Statistics No.5

COMMONWEALTH OF DOMINICA DE,MOGRAP'HIC STAT~STICS NO.5 2008 ICENTRAL STATISTICAL OFFICE, Ministry of Finance and Social Security, Roseau, Dominica. Il --- CONTENTS PAGE Preface 1 Analysis ll-Xlll Explanatory Notes XIV Map (Population Zones) XV Map (Topography) xvi TABLES Non-Institutional Population at Census Dates (1901 - 2001) 1 2 Non-Institutional Population, Births and Deaths by Sex At Census Years (1960 - 200I) 2 3 Non-Institutional Population by Sex and Five Year Age Groups (1970,1981,1991, and 2001) 3 4 Non-Institutional Population By Five Year Age Groups (1970,1981, 1991 and 2001) 4 5 Population By Parishes (1946 - 200 I) 5 6 Population Percentage Change and Intercensal Annual Rate of Change (1881 - 200 I) 6 7 Population Density By Land Area - 200I Census compared to 1991 Census 7 8 Births and Deaths by Sex (1990 - 2006) 8 9 Total Population Analysed by Births, Deaths and Net Migration (1990 - 2006) 9 10 Total Persons Moving into and out ofthe Population (1981 -1990, 1991 - 2000 and 2001 - 2005) 10 II Number ofVisas issued to Dominicans for entry into the United States of America and the French Territories (1993 - 2003) 11 12 Mean Population and Vital Rates (1992 - 2006) 12 13 Total Births by Sex and Age Group ofMother (1996 - 2006) 13 14 Total Births by Sex and Health Districts (1996 - 2006) 14 15 Total Births by Age Group ofMother (1996 - 2006) 15 15A Age Specific Fertility Rates ofFemale Population 15 ~ 44 Years not Attending School 1981. 1991 and 2001 Census 16 16 Age Specific Birth Rates (2002 - 2006) 17 17 Basic Demographic -

Free Downloads Dominica Story a History of the Island

Free Downloads Dominica Story A History Of The Island Paperback Publisher: UNSPECIFIED VENDOR ASIN: B000UC3CTY Average Customer Review: 4.8 out of 5 stars  See all reviews (6 customer reviews) Best Sellers Rank: #15,367,898 in Books (See Top 100 in Books) #40 in Books > History > Americas > Caribbean & West Indies > Dominica #23428 in Books > Reference > Writing, Research & Publishing Guides > Writing > Travel Here is a very interesting history of a Caribbean island most people in the U.S. may not know much about. It's written by a native Dominican, Lennox Honychurch, who has himself participated in some of the events of his country in the last 30-40 years, particularly in the country's politics. And, despite that, he does a remarkable job of keeping the whole narrative very objective, even when a tragic portion of that history involves his own family. I also found the history of Britain and France fighting over the island between the 7 Years War and the Napoleonic Wars very exciting as well. Also, Mr. Honychurch mixes in enough ethnography and social observation to give anyone an idea of the general character of the people, even if they have never visited the island. However, I do have one or two critiques. First, about two-thirds of the way through the book, Mr. Honychurch switches from a purely chronological structure to a purely thematic structure then switches back within the last 30-40 pages. Not that I can think of a better way to do it, considering some of the things he had to cover, but it is a little jarring to have that kind of a structural switch. -

Power Relations and Good Governance: a Social Network Analysis of the Evolution of the Integrity in Public Office Act in the Commonwealth of Dominica

POWER RELATIONS AND GOOD GOVERNANCE: A SOCIAL NETWORK ANALYSIS OF THE EVOLUTION OF THE INTEGRITY IN PUBLIC OFFICE ACT IN THE COMMONWEALTH OF DOMINICA Thèse Gérard JEAN-JACQUES Doctorat en science politique Philosophiae doctor (Ph.D) Québec, Canada © Gérard Jean-Jacques, 2016 POWER RELATIONS AND GOOD GOVERNANCE: A SOCIAL NETWORK ANALYSIS OF THE EVOLUTION OF THE INTEGRITY IN PUBLIC OFFICE ACT IN THE COMMONWEALTH OF DOMINICA Thèse Gérard JEAN-JACQUES Sous la direction de: Louis IMBEAU, directeur de recherche Mathieu OUIMET, codirecteur de recherche RÉSUMÉ: La Banque mondiale propose la bonne gouvernance comme la stratégie visant à corriger les maux de la mauvaise gouvernance et de faciliter le développement dans les pays en développement (Carayannis, Pirzadeh, Popescu & 2012; & Hilyard Wilks 1998; Leftwich 1993; Banque mondiale, 1989). Dans cette perspective, la réforme institutionnelle et une arène de la politique publique plus inclusive sont deux stratégies critiques qui visent à établir la bonne gouvernance, selon la Banque et d'autres institutions de Bretton Woods. Le problème, c’est que beaucoup de ces pays en voie de développement ne possèdent pas l'architecture institutionnelle préalable à ces nouvelles mesures. Cette thèse étudie et explique comment un état en voie de développement, le Commonwealth de la Dominique, s’est lancé dans un projet de loi visant l'intégrité dans la fonction publique. Cette loi, la Loi sur l'intégrité dans la fonction publique (IPO) a été adoptée en 2003 et mis en œuvre en 2008. Cette thèse analyse les relations de pouvoir entre les acteurs dominants autour de évolution de la loi et donc, elle emploie une combinaison de technique de l'analyse des réseaux sociaux et de la recherche qualitative pour répondre à la question principale: Pourquoi l'État a-t-il développé et mis en œuvre la conception actuelle de la IPO (2003)? Cette question est d'autant plus significative quand nous considérons que contrairement à la recherche existante sur le sujet, l'IPO dominiquaise diverge considérablement dans la structure du l'IPO type idéal.