Cambodia's Fisheries: Adecade of Changes and Evolution

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Diversity and Risk Patterns of Freshwater Megafauna: a Global Perspective

Diversity and risk patterns of freshwater megafauna: A global perspective Inaugural-Dissertation to obtain the academic degree Doctor of Philosophy (Ph.D.) in River Science Submitted to the Department of Biology, Chemistry and Pharmacy of Freie Universität Berlin By FENGZHI HE 2019 This thesis work was conducted between October 2015 and April 2019, under the supervision of Dr. Sonja C. Jähnig (Leibniz-Institute of Freshwater Ecology and Inland Fisheries), Jun.-Prof. Dr. Christiane Zarfl (Eberhard Karls Universität Tübingen), Dr. Alex Henshaw (Queen Mary University of London) and Prof. Dr. Klement Tockner (Freie Universität Berlin and Leibniz-Institute of Freshwater Ecology and Inland Fisheries). The work was carried out at Leibniz-Institute of Freshwater Ecology and Inland Fisheries, Germany, Freie Universität Berlin, Germany and Queen Mary University of London, UK. 1st Reviewer: Dr. Sonja C. Jähnig 2nd Reviewer: Prof. Dr. Klement Tockner Date of defense: 27.06. 2019 The SMART Joint Doctorate Programme Research for this thesis was conducted with the support of the Erasmus Mundus Programme, within the framework of the Erasmus Mundus Joint Doctorate (EMJD) SMART (Science for MAnagement of Rivers and their Tidal systems). EMJDs aim to foster cooperation between higher education institutions and academic staff in Europe and third countries with a view to creating centres of excellence and providing a highly skilled 21st century workforce enabled to lead social, cultural and economic developments. All EMJDs involve mandatory mobility between the universities in the consortia and lead to the award of recognised joint, double or multiple degrees. The SMART programme represents a collaboration among the University of Trento, Queen Mary University of London and Freie Universität Berlin. -

Downloads/ Scshandbook 2 12 08 Compressed.Pdf (Accessed on 6 June 2020)

water Article Conserving Mekong Megafishes: Current Status and Critical Threats in Cambodia Teresa Campbell 1,* , Kakada Pin 2,3 , Peng Bun Ngor 3,4 and Zeb Hogan 1 1 Department of Biology and Global Water Center, University of Nevada, Reno, NV 89557, USA; [email protected] 2 Centre for Biodiversity Conservation, Royal University of Phnom Penh, Phnom Penh 12156, Cambodia; [email protected] 3 Wonders of the Mekong Project, c/o Inland Fisheries Research and Development Institute, Phnom Penh 12300, Cambodia 4 Inland Fisheries Research and Development Institute, Fisheries Administration, Phnom Penh 12300, Cambodia; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +01-775-682-6066 Received: 2 June 2020; Accepted: 20 June 2020; Published: 25 June 2020 Abstract: Megafishes are important to people and ecosystems worldwide. These fishes attain a maximum body weight of 30 kg. Global population declines highlight the need for more information ≥ about megafishes’ conservation status to inform management and conservation. The northern Cambodian Mekong River and its major tributaries are considered one of the last refugia for Mekong megafishes. We collected data on population abundance and body size trends for eight megafishes in this region to better understand their conservation statuses. Data were collected in June 2018 using a local ecological knowledge survey of 96 fishers in 12 villages. Fishers reported that, over 20 years, most megafishes changed from common to uncommon, rare, or locally extirpated. The most common and rarest species had mean last capture dates of 4.5 and 95 months before the survey, respectively. All species had declined greatly in body size. -

Species of the Day: Mekong Giant Catfish

© Zeb Hogan Species of the Day: Mekong Giant Catfish The Mekong Giant Catfish, Pangasianodon gigas, is classified as ‘Critically Endangered’ on the IUCN Red List of Threatened SpeciesTM. It is the world’s largest freshwater fish and is found only in the parts of the Mekong River basin that run through Cambodia, Laos, Thailand, Vietnam and possibly Burma and China. The Mekong Giant Catfish has been subject to overfishing for many years.As a result of Geographical range damming and clearance of the flooded forest near the Tonle Sap Lake, its habitat has been www.iucnredlist.org severely disrupted effecting its migration, spawning, eating and breeding habits. www.global.wetlands.org Help Save Species Legislation restricting the hunting of Mekong Giant Catfish exists but is rarely enforced. Artificially spawned individuals have been released into the River Mekong since 1985, and captive breeding (reliant on wild-caught brood stock) has been taking place since 2001. The potentially highly significant impact of dams needs urgent assessment, as recent studies suggest that all large migratory catfish will be eliminated from the river system if two or more mainstream dams are constructed without effective adaptation measures. The production of the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species™ is made possible through the IUCN Red List Partnership: Species of the Day IUCN (including the Species Survival Commission), BirdLife is sponsored by International, Conservation International, NatureServe and Zoological Society of London.. -

Giant Fish of the Mekong the Mekong River © Daniel Cheong / Executive Summary WWF Greater Mekong Programme ©

Riverof Giants Giant Fish of the Mekong The Mekong River © Daniel Cheong / www.flickr.com Executive Summary WWF Greater Mekong Programme © The worlds biggest freshwater fish and 4 out of the top ten As ambassadors of the Greater Mekong region, vulnerable to giant freshwater fish species can be found in the Mekong River fishing pressure and changes in the river environment, the which flows through Cambodia, China, Lao PDR, Myanmar, status of the giant fish is one indicator of the health and Thailand and Vietnam. More giants inhabit this mighty river ecological integrity of the Mekong. The well-being of these than any other on Earth. species is therefore closely linked to the sustainable management of the region and to limiting the environmental Little is known about these magnificent species of the Greater impacts of increased regional economic activity and Mekong region, some attaining five metres in length and over integration. half a ton in weight. What is known is that their future is uncertain. Any impact on the ecological balance of the river also threatens the sustainability of the aquatic resources that support Populations of the Mekong giant catfish have plummeted 90 millions of people. There are at least 50 migratory species per cent in just two decades, whilst the giant dog-eating catfish which are highly vulnerable to mainstream dam development. is seldom seen now in the wild. Living amongst the new These make up between 40-70 per cent of the catch of fish in emerging economic powers of Asia, a combination of the Mekong. infrastructure development, habitat destruction and overharvesting, is quickly eroding populations of these The 1995 agreement of the Mekong River Commission should extraordinary species. -

(RIS), Sage 13 Appendix 1. Table 1: Fish Species of Conservation

,QIRUPDWLRQ6KHHWRQ5DPVDU:HWODQGV 5,6 SDJH Appendix 1. Table 1: Fish Species of Conservation Concern Occurring in the TSBR1 Species International Status Significance Mekong Giant Catfish IUCN Critically Fishing Lot No. 2 may be an important Pangasianodon gigas Endangered; CITES nursery area Appendix I Leaping Barb IUCN Critically not recorded from Tonle Sap Lake, but Chela caeruleostigmata Endangered possibly occurs Jullien’s Golden Carp IUCN Endangered; recorded from Tonle Sap Lake Probarbus jullieni CITES Appendix 2 Laotian Shad IUCN Endangered populations have recently drastically declined Tenualosa thibaudeaui due to factors outside of the Tonle Sap Tricolor Sharkminnow IUCN Endangered depicted on FiA’s Endangered Fishes of Balantiocheilos melanopterus Cambodia Asian Bonytongue/Asian IUCN Endangered; occurrence in TSBR not confirmed Arowana CITES Appendix I Scleropages formosus Thicklip Barb IUCN Data Deficient recorded in Tonle Sap, but little known Probarbus labeamajor Giant Pangasius IUCN Data Deficient becoming increasingly rare throughout its Pangasius sanitwongsei range Giant Barb not listed, but requires numbers have declined drastically Catlocarpio siamensis urgent evaluation and immediate conservation attention Puntioplites bulu not listed formerly common, but has recently become very rare. Depicted on FiA’s Endangered Fishes of Cambodia. Occurrence in TSBR requires confirmation. Sabretoothed Thryssa not listed depicted on FiA’s Endangered Fishes of Lycothrissa crocodilus Cambodia Four-barred Tigerfish not listed occurrence in TSBR not confirmed. Depicted Datnioides quadrifasciatus on FiA’s Endangered Fishes of Cambodia Wallago leeri not listed occurrence in TSBR not confirmed. Depicted on FiA’s Endangered Fishes of Cambodia Albulichthys albuloides not listed depicted on FiA’s Endangered Fishes of Cambodia Elephant-ear Gourami not listed occurrence in TSBR not confirmed. -

Mysterious MEKONG

GREATERREPORT MEKONGGREATER REPORTMEKONG 2014 WWF-Greater Mekong MysTERiOus MEKONG NEw sPEciEs discOvERiEs 2012-2013 WWF is one of the world’s largest and most experienced independent conservation organizations, with over 5 million supporters and a global network active in more than 100 countries. WWF’s mission is to stop the degradation of the planet’s natural environment and to build a future in which humans live in harmony with nature, by: conserving the world’s biological diversity, ensuring that the use of renewable natural resources is sustainable, and promoting the reduction of pollution and wasteful consumption. Produced by Christian Thompson (the green room), Maggie Kellogg, Thomas Gray and Sarah Bladen (WWF) Published in 2014 by WWF-World Wide Fund For Nature (Formerly World Wildlife Fund). © Text 2014 WWF All rights reserved Front cover The Cambodian Tailorbird (Orthotomus chaktomuk), a new bird species discovered in 2013 © James Eaton / Birdtour Asia. © Gordon Congdon / WWF-Greater Mekong A tributary of the Mekong River flows through unbroken and highly biodiverse rainforests of the Greater Mekong region, Cambodia. At a glance, by country... Cambodia 13 China 116 (Guangxi / Yunnan) Laos 32 Myanmar 26 Thailand 117 Vietnam 99 © Peter Jäger / Senckenberg Research Institute, Frankfurt Note: The sum of the above figures does not equal the total number of new species discovered in 2012 and 2013, as some species have a distribution spanning more than one country. Blind huntsman spider, Sinopoda scurion, in its original cave habitat in Laos.s An extraordinary 367 new species were discovered in the Greater Mekong in 2012 and 2013. Among the species newly described by EXEuv c Ti E scientists are 290 plants, 24 fish, 21 amphibians, 28 reptiles, 1 bird and 3 mammals [see Appendix]. -

Imperiled Giant Fish and Mainstream Dams in the Lower Mekong Basin: Assessment of Current Status, Threats, and Mitigation

IMPERILED GIANT FISH AND MAINSTREAM DAMS IN THE LOWER MEKONG BASIN: ASSESSMENT OF CURRENT STATUS, THREATS, AND MITIGATION Report prepared by Zeb Hogan, Ph.D. University of Nevada, Reno Reno, U.S.A. Director, National Geographic Society Megafishes Project National Geographic Society Fellow United Nations Convention on Migratory Species Scientific Councilor for Fish April 15 2011 Executive Summary This report focuses on the impacts of the Xayaburi dam on five of the Mekong’s largest fish and provides a short discussion about potential impacts to other threatened and migratory species. From a biodiversity and fisheries perspective, the environmental impact assessment (EIA) of the dam developer (Ch. Karnchang Public Company Limited) has a number of serious shortcomings. The field portion of the fisheries assessment was completed extremely quickly, relied on a very limited number of sampling techniques, and consisted of only 6 sampling locations spread over just 22 km of river. Given the high diversity of Mekong fish, the seasonality of catches, their migratory nature, and – in the case of threatened species – their rarity, the field survey methodology was grossly inadequate. The developer’s EIA cannot be used to predict with any accuracy the serious impacts of the Xayaburi dam on threatened or migratory fish. All available evidence suggests the Xayaburi dam will have serious negative impacts on the migratory and imperiled fish of the lower Mekong River and may drive the Mekong’s two largest freshwater fish species, the Mekong giant catfish and the giant pangasius catfish to extinction. Introduction The Mekong River is one of the most biodiverse and productive rivers on Earth. -

Catchculturevol10-No.1.2-Lao.Pdf

Hydrology 4 January 2005 Catch and Culture Volume 10, No. 1. Hydrology Catch and Culture Volume 10, No. 1. January 2005 5 Hydrology 6 January 2005 Catch and Culture Volume 10, No. 1. Hydrology Catch and Culture Volume 10, No. 1. January 2005 7 Fisheries 14 18 13 16 12 Catc h 11 14 10 12 9 10 8 Catch (000 tonnes) Water Level 7 8 Average Water level over 30 days (m) 6 6 5 4 4 1995-6 1996-7 1997-8 1998-9 1999-0 2000-1 2001-2 2002-3 2003-4 Year 8 January 2005 Catch and Culture Volume 10, No. 1. Fisheries Catch and Culture Volume 10, No. 1. January 2005 9 Fisheries 12 10 8 6 Water Level (m) 4 2 0 1/1/95 1/1/96 31/12/96 31/12/97 31/12/98 31/12/99 30/12/00 30/12/01 30/12/02 30/12/03 10 January 2005 Catch and Culture Volume 10, No. 1. Fisheries techniques Catch and Culture Volume 10, No. 1. January 2005 11 Fisheries techniques 12 January 2005 Catch and Culture Volume 10, No. 1. Fisheries techniques Catch and Culture Volume 10, No. 1. January 2005 13 Biology Siluridae Siluriformes Mastacembelidae Soleidae Cynoglossidae Anguillidae 14 January 2005 Catch and Culture Volume 10, No. 1. Biology Syngnathidae Notopteridae Batrachoididae Betta splendens Ariidae Catch and Culture Volume 10, No. 1. January 2005 15 Biology Polynemidae Gobiidae 16 January 2005 Catch and Culture Volume 10, No. 1. Fisheries Management Catch and Culture Volume 10, No. -

Mekong Giant Catfish Report English Pdf 1.18 MB

PROGRAMME HOLISTIQUE DE CONSERVATIONES FORETS A MADAGASCAR © Zeb Hogan A MEKONG GIANT CURRENT STATUS, THREATS AND PRELIMINARY CONSERVATION MEASURES FOR THE CRITICALLY ENDANGERED MEKONG GIANT CATFISH Report prepared for WWF-Greater Mekong by Dr. Zeb Hogan Department of Natural Resources and Environmental Science University of Nevada, Reno, U.S ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The information contained in this report was gathered over several years with the assistance of many people. Special thanks to Sam Nuov, Xaypladeth Choulamany, Nicolaas van Zalinge, Chris Barlow, Chumnarn Pongsri, Kongpheng Bouakhamvongsa, Peter-John Meynell, Latsamay Sylavong, Richard Friend, Chainarong Srettacheua, Yaowalak Srikhampa, Sayan Khamneung, Lek Kansuntisukmongkol, Piak Kansuntisukmongkol, Praichon Intanujit, Noppakwan Inthapan, Roger Mollot, Victor Cowling, Sylvia Maeght, WWF, the National Geographic Society, the staff of the Cambodian Department of Fisheries, LARREC, the Thai Department of Fisheries, and the helpful fishermen of the lower Mekong River Basin. This report was produced with funding support from the Critical Ecosystem Partnership Fund (CEPF). The Critical Ecosystem Partnership Fund is a joint initiative of l’Agence Française de Développement, Conservation International, the Global Environment Facility, the Government of Japan, the MacArthur Foundation and the World Bank. A fundamental goal is to ensure civil society is engaged in biodiversity conservation. www.cepf.net Front cover photo: a Cambodian man observes a Mekong giant catfish on the Tonle Sap river. -

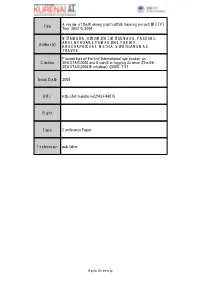

Title a Review of the Mekong Giant Catfish Tracking Project (MCTP)

A review of the Mekong giant catfish tracking project (MCTP) Title from 2002 to 2004 MITAMURA, HIROMICHI; MITSUNAGA, YASUSHI; ARAI, NOBUAKI; YAMAGISHI, YUKIKO; Author(s) KHACHAPHICHAT, METHA; VIPUTHANUMAS, THAVEE Proceedings of the 2nd International symposium on Citation SEASTAR2000 and Asian Bio-logging Science (The 6th SEASTAR2000 Workshop) (2005): 7-11 Issue Date 2005 URL http://hdl.handle.net/2433/44075 Right Type Conference Paper Textversion publisher Kyoto University A review of the Mekong giant catfish tracking project (MCTP) from 2002 to 2004 1 2 1 3 HROMICHI MITAMURA , YASUSHI MITSUNAGA , NOBUAKI ARAI, YUKIKO YAMAGISHI , KHACHA METHA , 4 THAVEE VIPUTHANUMAS 1Graduate School of Informatics, Kyoto University, Kyoto 606-8501, Japan Email: [email protected] 2Faculty of Agriculture, Kinki University, Nara 631-8505, Japan 3 Phayao Inland Fisheries Station, Phayao Province, 19000, Thailand 4Inland Fisheries Research and Development Bureau, Kasetsart University, Bangkok, 10900, Thailand ABSTRACT For the conservation and successful stock enhancement of the endangered species Mekong giant catfish Pangasianodon gigas, an understanding of its movement patterns and behavior is indispensable. The Mekong giant catfish tracking project (MCTP) has been begun to measure the movements of hatchery-reared Mekong giant catfish using acoustic telemetry and bio-logging technology in the Mae peum reservoir and Mekong River. Research in the Mae peum reservoir demonstrated that fish showed distinctive diel vertical movement and the swimming depth was limited by the thermocline or dissolved oxygen stratification. Fish also displayed diel horizontal movement between inshore at night and offshore areas during the day. Researchers in the Mekong River presented the first records of upstream and downstream movement of Mekong giant catfish for up to 97 days. -

Download the WFMD 2016 Factsheet

WHAT IS THIS FISH? The World’s Giant, Endangered Migratory Fish Mekong giant catfish Taimen One of the largest and most iconic fi sh of Or the giant Eurasian trout, isn’t known for Southeast Asia, the Mekong giant catf ish is long distance migrati ons, and yet populati ons symbolic of the health of the Mekong River. A of taimen decline in rivers that are fragmented Mekong River endemic, the huge fi sh grows to or dammed. Taimen seem to do best in free 10 feet and 650 pounds. It makes long distance fl owing rivers. Research from Mongolia shows migrati ons out of the Tonle Sap Lake and into that taimen are capable of movements of over the mainstream Cambodian Mekong. Geneti c 100 miles and oft en return to the same sites evidence suggests that the Mekong giant year aft er year. While more study is needed, catf ish also migrates from Cambodia into Lao it’s clear that taimen do best in healthy rivers PDR and Thailand, a journey of almost 1000 with clean water and abundant prey. miles. ©Brant Allen White sturgeon Freshwater sawfish Are found from California to Alaska. Most Sawfi sh get their name from their saw-like populati ons are anadromous, migrati ng FRESHWATER SAWFISH snout. Freshwater sawfi sh spend the early from fresh water to the sea and back again part of their life in fresh water, then move to complete their life cycle. White sturgeon into coastal waters as they mature. Habitat populati ons are healthiest in undammed degradati on, as well as dams and overfi shing stretches of the Columbia and Sacramento have taken their toll on the freshwater sawfi sh Rivers and largely free fl owing secti ons like the which is now listed as Criti cally Endangered. -

Overfishing of Inland Waters

Articles Overfishing of Inland Waters J. DAVID ALLAN, ROBIN ABELL, ZEB HOGAN, CARMEN REVENGA, BRAD W. TAYLOR, ROBIN L. WELCOMME, AND KIRK WINEMILLER Inland waters have received only slight consideration in recent discussions of the global fisheries crisis, even though inland fisheries provide much-needed protein, jobs, and income, especially in poor rural communities of developing countries. Systematic overfishing of fresh waters is largely unrecognized because of weak reporting and because fishery declines take place within a complex of other pressures. Moreover, the ecosystem consequences of changes to the species, size, and trophic composition of fish assemblages are poorly understood. These complexities underlie the paradox that overexploitation of a fishery may not be marked by declines in total yield, even when individual species and long-term sustainability are highly threatened. Indeed, one of the symptoms of intense fishing in inland waters is the collapse of particular stocks even as overall fish production rises—a biodiversity crisis more than a fisheries crisis. Keywords: overfishing, fishing down, freshwater biodiversity, ecosystem function, fish harvest verexploitation of the world’s fisheries is the inland fisheries. Although there are no global estimates of the Osubject of much recent concern (FAO 2002, Pauly et al. number of people engaged in inland fisheries, in China alone, 2002, Hilborn et al. 2003). Although the global production of more than 80% of the 12 million reported fishers are engaged fish and fishery products continues to grow, the harvest from in inland capture fishing and aquaculture (Kura et al. 2004). capture fisheries has stagnated over the last decade. Today nu- The contribution of fisheries to the global food supply is merous fish stocks and species have declined since their his- also significant.