Quercus Ilicifolia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Oak Diversity and Ecology on the Island of Martha's Vineyard

Oak Diversity and Ecology on the Island of Martha’s Vineyard Timothy M. Boland, Executive Director, The Polly Hill Arboretum, West Tisbury, MA 02575 USA Martha’s Vineyard is many things: a place of magical beauty, a historical landscape, an environmental habitat, a summer vacation spot, a year-round home. The island has witnessed wide-scale deforestation several times since its settlement by Europeans in 1602; yet, remarkably, existing habitats rich in biodiversity speak to the resiliency of nature. In fact, despite repeated disturbances, both anthropogenic and natural (hurricanes and fire), the island supports the rarest ecosystem (sand plain) found in Massachusetts (Barbour, H., Simmons, T, Swain, P, and Woolsey, H. 1998). In particular, the scrub oak (Quercus ilicifolia Wangenh.) dominates frost bottoms and outwash plains sustaining globally rare lepidopteron species, and formerly supported the existence of an extinct ground-dwelling bird, a lesson for future generations on the importance of habitat preservation. European Settlement and Early Land Transformation In 1602 the British merchant sailor Bartholomew Gosnold arrived in North America having made the six-week boat journey from Falmouth, England. Landing on the nearby mainland the crew found abundant codfish and Gosnold named the land Cape Cod. Further exploration of the chain of nearby islands immediately southwest of Cape Cod included a brief stopover on Cuttyhunk Island, also named by Gosnold. The principle mission was to map and explore the region and it included a dedicated effort to procure the roots of sassafras (Sassafras albidum (Nutt.) Nees) which were believed at the time to be medicinally valuable (Banks, 1917). -

Scientific Name Common Name NATURAL ASSOCIATIONS of TREES and SHRUBS for the PIEDMONT a List

www.rainscapes.org NATURAL ASSOCIATIONS OF TREES AND SHRUBS FOR THE PIEDMONT A list of plants which are naturally found growing with each other and which adapted to the similar growing conditions to each other Scientific Name Common Name Acer buergeranum Trident maple Acer saccarum Sugar maple Acer rubrum Red Maple Betula nigra River birch Trees Cornus florida Flowering dogwood Fagus grandifolia American beech Maple Woods Liriodendron tulipifera Tulip-tree, yellow poplar Liquidamber styraciflua Sweetgum Magnolia grandiflora Southern magnolia Amelanchier arborea Juneberry, Shadbush, Servicetree Hamamelis virginiana Autumn Witchhazel Shrubs Ilex opaca American holly Ilex vomitoria*** Yaupon Holly Viburnum acerifolium Maple leaf viburnum Aesulus parvilflora Bottlebrush buckeye Aesulus pavia Red buckeye Carya ovata Shadbark hickory Cornus florida Flowering dogwood Halesia carolina Crolina silverbell Ilex cassine Cassina, Dahoon Ilex opaca American Holly Liriodendron tulipifera Tulip-tree, yellow poplar Trees Ostrya virginiana Ironwood Prunus serotina Wild black cherry Quercus alba While oak Quercus coccinea Scarlet oak Oak Woods Quercus falcata Spanish red oak Quercus palustris Pin oak Quercus rubra Red oak Quercus velutina Black oak Sassafras albidum Sassafras Azalea nudiflorum Pinxterbloom azalea Azalea canescens Piedmont azalea Ilex verticillata Winterberry Kalmia latifolia Mountain laurel Shrubs Rhododenron calendulaceum Flame azalea Rhus copallina Staghorn sumac Rhus typhina Shining sumac Vaccinium pensylvanicum Low-bush blueberry Magnolia -

Oaks (Quercus Spp.): a Brief History

Publication WSFNR-20-25A April 2020 Oaks (Quercus spp.): A Brief History Dr. Kim D. Coder, Professor of Tree Biology & Health Care / University Hill Fellow University of Georgia Warnell School of Forestry & Natural Resources Quercus (oak) is the largest tree genus in temperate and sub-tropical areas of the Northern Hemisphere with an extensive distribution. (Denk et.al. 2010) Oaks are the most dominant trees of North America both in species number and biomass. (Hipp et.al. 2018) The three North America oak groups (white, red / black, and golden-cup) represent roughly 60% (~255) of the ~435 species within the Quercus genus worldwide. (Hipp et.al. 2018; McVay et.al. 2017a) Oak group development over time helped determine current species, and can suggest relationships which foster hybridization. The red / black and white oaks developed during a warm phase in global climate at high latitudes in what today is the boreal forest zone. From this northern location, both oak groups spread together southward across the continent splitting into a large eastern United States pathway, and much smaller western and far western paths. Both species groups spread into the eastern United States, then southward, and continued into Mexico and Central America as far as Columbia. (Hipp et.al. 2018) Today, Mexico is considered the world center of oak diversity. (Hipp et.al. 2018) Figure 1 shows genus, sub-genus and sections of Quercus (oak). History of Oak Species Groups Oaks developed under much different climates and environments than today. By examining how oaks developed and diversified into small, closely related groups, the native set of Georgia oak species can be better appreciated and understood in how they are related, share gene sets, or hybridize. -

THAISZIA the Role of Biodiversity Conservation in Education At

Thaiszia - J. Bot., Košice, 25, Suppl. 1: 35-44, 2015 http://www.bz.upjs.sk/thaiszia THAISZIAT H A I S Z I A JOURNAL OF BOTANY The role of biodiversity conservation in education at Warsaw University Botanic Garden 1 1 IZABELLA KIRPLUK & WOJCIECH PODSTOLSKI 1Botanic Garden, Faculty of Biology, University of Warsaw, Al. Ujazdowskie 4, 00-478 Warsaw, Poland, +48 22 5530515 [email protected], [email protected] Kirpluk I. & Podstolski W. (2015): The role of biodiversity conservation in education at Warsaw University Botanic Garden. – Thaiszia – J. Bot. 25 (Suppl. 1): 35-44. – ISSN 1210-0420. Abstract: The Botanic Garden of Warsaw University, established in 1818, is one of the oldest botanic gardens in Poland. It is located in the centre of Warsaw within its historic district. Initially it covered an area of 22 ha, but in 1834 the garden area was reduced by 2/3, and has remained unchanged since then. Today, the cultivated area covers 5.16 ha. The plant collection of 5000 taxa forms the foundation for a diverse range of educational activities. The collection of threatened and protected Polish plant species plays an especially important role. The Botanic Garden is a scientific and didactic unit. Its educational activities are aimed not only at university students, biology teachers, and school and preschool children, but also at a very wide public. Within the garden there are designed and well marked educational paths dedicated to various topics. Clear descriptions of the paths can be found in the garden guide, both in Polish and English. Specially designed educational games for children, Green Peter and Green Domino, serve a supplementary role. -

Reproduction and Gene Flow in the Genus Quercus L

Review article Reproduction and gene flow in the genus Quercus L A Ducousso H Michaud R Lumaret 1 INRA, BP 45, 33611 Gazinet-Cestas; 2 CEFE/CNRS, BP 5051, 34033 Montpellier Cedex, France Summary — In this paper we review the characteristics of the floral biology, life cycle and breeding system in the genus Quercus. The species of this genus are self-incompatible and have very long life spans. The focus of our review is on the effects of gene flow on the structuration of genetic varia- tion in these species. We have examined the influence of gene flow in 2 ways: 1) by measuring the physical dispersal of pollen, seed and vegetative organs; and 2) by using nuclear and cytoplasmic markers to estimate genetic parameters (Fis, Nm). These approaches have shown that nuclear (iso- zyme markers) as well as cytoplasmic (chloroplastic DNA) gene flow is usually high, so that very low interspecific differentiation occurs. However, intraspecific differentiation is higher for the cytoplasmic DNA than for the nuclear isozyme markers. floral biology / life cycle / breeding system / gene flow / oak Résumé — Système de reproduction et flux de gènes chez les espèces du genre Quercus. Les caractéristiques de la biologie florale, du cycle de vie et du système de reproduction ont été analysées pour les espèces du genre Quercus. Ces espèces sont auto-incompatibles et à très lon- gue durée de vie. Les effets des flux de gènes sur la structuration de la variabilité génétique ont aussi été étudiés de 2 manières. D’une part, grâce aux mesures de la dispersion du pollen, des graines et des organes végétatifs, et, d’autre part, en utilisant des paramètres génétiques (Fis, Nm) obtenus à partir des marqueurs nucléaires et cytoplasmiques. -

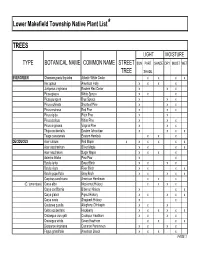

Native Plant List Trees.XLS

Lower Makefield Township Native Plant List* TREES LIGHT MOISTURE TYPE BOTANICAL NAME COMMON NAME STREET SUN PART SHADE DRY MOIST WET TREE SHADE EVERGREEN Chamaecyparis thyoides Atlantic White Cedar x x x x IIex opaca American Holly x x x x Juniperus virginiana Eastern Red Cedar x x x Picea glauca White Spruce x x x Picea pungens Blue Spruce x x x Pinus echinata Shortleaf Pine x x x Pinus resinosa Red Pine x x x Pinus rigida Pitch Pine x x Pinus strobus White Pine x x x Pinus virginiana Virginia Pine x x x Thuja occidentalis Eastern Arborvitae x x x x Tsuga canadensis Eastern Hemlock xx x DECIDUOUS Acer rubrum Red Maple x x x x x x Acer saccharinum Silver Maple x x x x Acer saccharum Sugar Maple x x x x Asimina triloba Paw-Paw x x Betula lenta Sweet Birch x x x x Betula nigra River Birch x x x x Betula populifolia Gray Birch x x x x x Carpinus caroliniana American Hornbeam x x x (C. tomentosa) Carya alba Mockernut Hickory x x x x Carya cordiformis Bitternut Hickory x x x Carya glabra Pignut Hickory x x x x x Carya ovata Shagbark Hickory x x Castanea pumila Allegheny Chinkapin xx x Celtis occidentalis Hackberry x x x x x x Crataegus crus-galli Cockspur Hawthorn x x x x Crataegus viridis Green Hawthorn x x x x Diospyros virginiana Common Persimmon x x x x Fagus grandifolia American Beech x x x x PAGE 1 Exhibit 1 TREES (cont'd) LIGHT MOISTURE TYPE BOTANICAL NAME COMMON NAME STREET SUN PART SHADE DRY MOIST WET TREE SHADE DECIDUOUS (cont'd) Fraxinus americana White Ash x x x x Fraxinus pennsylvanica Green Ash x x x x x Gleditsia triacanthos v. -

Exhibit L1 – List of Native Overstory Trees in Frederick County *Aste

List of Native Overstory Trees In Middletown, MD Source: Exhibit L1 – List of Native Overstory Trees in Frederick County *Asterisks indicate additions to List made because of naturalization or other reasons, assessed by Frederick County Planning Department Conifers - Scientific Name Common Name(s) (and Broad-leafed Evergreens) Juniperus virginiana (Eastern) Red Cedar Pinus echinata Shortleaf Pine Pinus punguns Table Mountain Pine Pinus rigida Pitch Pine Pinus strobus White Pine Pinus virginiana Virginia Pine *Taxodium distichum *Bald Cypress Tsuga canadensis Eastern Hemlock Hardwoods – Scientific Name Common Name(s) Acer negundo Box-Elder Acer nigrum Black Maple Acer rubrum Red Maple Acer saccharinum Silver Maple (Invasive Native – not recommended) Acer saccharum Sugar Maple Alnus rugosa, (serrulata) Smooth Alder (Hazel Alder) Betula lenta Black Birch (Sweet Birch) Betula nigra River Birch (Black Birch) Carpinus caroliniana Blue Beech (American Hornbeam, Musclewood, Ironwood) Carya cordiformis Bitternut Hickory Carya glabra Pignut Hickory Carya ovata Shagbark Hickory Carya pallida Sand Hickory Carya tomentosa Mockernut Hickory Castanea dentata (American) Chestnut Castanea pumila Eastern or Allegheny Chinkapin Celtis occidentalis Hackberry Fagus grandifolia (American) Beech Fraxinus species–There is a temporary, albeit indefinite ban on Ash trees in Frederick County. Juglans cinerea Butternut Juglans nigra Black Walnut *Liquidambar styraciflua *Sweet Gum Liriodendron tulipifera Tulip Tree (Tulip Poplar) Magnolia acuminata Cucumber Tree -

Vegetation Classification and Mapping Project Report

U.S. Geological Survey-National Park Service Vegetation Mapping Program Acadia National Park, Maine Project Report Revised Edition – October 2003 Mention of trade names or commercial products does not constitute endorsement or recommendation for use by the U. S. Department of the Interior, U. S. Geological Survey. USGS-NPS Vegetation Mapping Program Acadia National Park U.S. Geological Survey-National Park Service Vegetation Mapping Program Acadia National Park, Maine Sara Lubinski and Kevin Hop U.S. Geological Survey Upper Midwest Environmental Sciences Center and Susan Gawler Maine Natural Areas Program This report produced by U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey Upper Midwest Environmental Sciences Center 2630 Fanta Reed Road La Crosse, Wisconsin 54603 and Maine Natural Areas Program Department of Conservation 159 Hospital Street 93 State House Station Augusta, Maine 04333-0093 In conjunction with Mike Story (NPS Vegetation Mapping Coordinator) NPS, Natural Resources Information Division, Inventory and Monitoring Program Karl Brown (USGS Vegetation Mapping Coordinator) USGS, Center for Biological Informatics and Revised Edition - October 2003 USGS-NPS Vegetation Mapping Program Acadia National Park Contacts U.S. Department of Interior United States Geological Survey - Biological Resources Division Website: http://www.usgs.gov U.S. Geological Survey Center for Biological Informatics P.O. Box 25046 Building 810, Room 8000, MS-302 Denver Federal Center Denver, Colorado 80225-0046 Website: http://biology.usgs.gov/cbi Karl Brown USGS Program Coordinator - USGS-NPS Vegetation Mapping Program Phone: (303) 202-4240 E-mail: [email protected] Susan Stitt USGS Remote Sensing and Geospatial Technologies Specialist USGS-NPS Vegetation Mapping Program Phone: (303) 202-4234 E-mail: [email protected] Kevin Hop Principal Investigator U.S. -

LEAFLET an Identification Guide of Common Species of Trees Found

THE EDISON LEAFLET An Identification Guide of Common Species of Trees Found Within ^ EDISON TOWNSHIP, NJ by Stephen Paul Yuhas Contains information for the identification of %Q separate species - Field guide done as a Boy Scout Eagle Service Project, October 28, 1983 Edison Twp. Fob. Library 340 Plainfield Ave. Edison, N. J. 08817 - Information gathered and compiled by members of Boy Scout Troop Number 53 Our Lady of Peace Church - Fords, New Jersey The Edison Leaflet Troop 53 Fords, N«J Stephen Yuhas October 28, 1983 This guide done as an Eagle Scout Service Project is intended to offer a comprehensive field guide for the identification of local tree species. Hopefully, it will emphasize the importance of such species and arouse concern for the future of their existence. This guide outlines the general description, habitat, and most important commercial uses of each specimen. As an identification aid this collection will serve to educate those seeking to understand our need of local trees even in a suburban town such as Edison Township, New Jersey, Table of Contents Groupings Page FAGACEAE ( Oaks, Beeches, Chestnuts ) 1-11 ACERACEAE ( Maples ) 12-1? CAPRIFOLIACEAE ( Viburnums ) 18-19 SALICACEAE ( Cottonwoods, Aspens, Poplars, Willows ) 20-25 HAMAMELIDACEAE ( Sweetgum, Witch-Hazel ) 26-2? LAURACEAE ( Sassafras, Spicebush ) 28-29 ULMACEAE ( Elms ) 30-32 BETHLACEAE ( Birches, Hornbeam, Hophornbeam ) 33-38 MAGNOLIACEAE ( Tuliptree, Cucumbertree ) 39-40 JUGLANDACEAE ( Hickories, Walnuts ) 41-43 CORNACEAE ( Dogwood ) 44 PLATANACEAE ( Sycamore -

An Updated Infrageneric Classification of the North American Oaks

Article An Updated Infrageneric Classification of the North American Oaks (Quercus Subgenus Quercus): Review of the Contribution of Phylogenomic Data to Biogeography and Species Diversity Paul S. Manos 1,* and Andrew L. Hipp 2 1 Department of Biology, Duke University, 330 Bio Sci Bldg, Durham, NC 27708, USA 2 The Morton Arboretum, Center for Tree Science, 4100 Illinois 53, Lisle, IL 60532, USA; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: The oak flora of North America north of Mexico is both phylogenetically diverse and species-rich, including 92 species placed in five sections of subgenus Quercus, the oak clade centered on the Americas. Despite phylogenetic and taxonomic progress on the genus over the past 45 years, classification of species at the subsectional level remains unchanged since the early treatments by WL Trelease, AA Camus, and CH Muller. In recent work, we used a RAD-seq based phylogeny including 250 species sampled from throughout the Americas and Eurasia to reconstruct the timing and biogeography of the North American oak radiation. This work demonstrates that the North American oak flora comprises mostly regional species radiations with limited phylogenetic affinities to Mexican clades, and two sister group connections to Eurasia. Using this framework, we describe the regional patterns of oak diversity within North America and formally classify 62 species into nine major North American subsections within sections Lobatae (the red oaks) and Quercus (the Citation: Manos, P.S.; Hipp, A.L. An Quercus Updated Infrageneric Classification white oaks), the two largest sections of subgenus . We also distill emerging evolutionary and of the North American Oaks (Quercus biogeographic patterns based on the impact of phylogenomic data on the systematics of multiple Subgenus Quercus): Review of the species complexes and instances of hybridization. -

Minutes of the 990 Meeting 12 September 2003 Arthur V. Gilman

New England Botanical Club - Minutes of the 990th Meeting 12 September 2003 Arthur V. Gilman, Recording Secretary pro tempore The 763rd meeting of the New England Botanical Club, being the 990th since its original organization was held at the University of Massachusetts-Boston Field Station on Polpis Rd., Nantucket, MA. The fall away meeting was well attended by over 25 members and guests. Following brief remarks and remembrances of long-time Club member Dr. Wesley N. Tiffney, Jr., who ran the field station for many years, the Club welcomed Dr. Ernie Steinauer, Director of the Massachusetts Audubon Society’s programs on Nantucket, who spoke on “Restoring and Maintaining Nantucket’s Rare Plant Communities.” The particular Nantucket communities of most concern from a botanical perspective are sandplain grassland, which is considered globally endangered, and coastal heathland, which is considered globally threatened. Rare species of these habitats include butterfly-weed (Asclepias tuberosa), bushy rockrose (Helianthemum dumosum), broom crowberry (Corema conradii), silvery aster (Aster concolor), New England blazing star (Liatris borealis var. novae-angliae), and lion’s-foot (Prenanthes serpentaria). There is a serious debate about the original extent of these habitats. In presettlement times (when there a was large but mostly seasonal population of Native Americans) they may have been limited to immediate coastal areas, where salt spray reduced woody plant cover. In any case, it is apparent that these plant communities were in large part maintained over a period of more than 200 years by sheep-grazing, which was at times quite intensive (in 1700 there were 17,000 sheep on the island). -

Quercus and Lithocarpus

"Uqog"Vjqwijvu"qp"Gxqnwvkqpct{"cpf"Rj{nqigpgvke" Perspectives in the Oaks - Quercus and Lithocarpus J. Smartt and R.J. White, School of Biological Sciences, University of Southampton, United Kingdom Introduction - the family Hcicegcg Cp"korqtvcpv"lwuvkÞecvkqp"hqt"ectt{kpi"qwv"gzrgtkogpvcn"vczqpqoke"uvwfkgu"qp" c"nctig"itqwr"uwej"cu"vjg"qcmu"ku"vjg"dgnkgh"vjcv"vjgug"ecp"jgnr"vq"tguqnxg"fkhÞewnvkgu" cpf"codkiwkvkgu"yjkej"vjg"encuukecn"vczqpqoke"crrtqcejgu"ecppqv0"Vjg"qcmu"ctg"c" widely distributed and species-rich group with a complex evolutionary history, and it is therefore helpful to view our present perceptions of the oaks particularly in the dtqcfgt"eqpvgzv"qh"vjg"hcokn{"vq"yjkej"vjg{"dgnqpi0 The Fagaceae is not a large family; there are ten recognised genera (Nixon, 3;:;+0"Fagus - the beeches, Nothofagus - the southern beeches, Castanea - the chestnuts, Castanopsis and Chrysolepis - the chinkapins and two genera of oaks, Lithocarpus and Quercus. In terms of species richness, the oak genera are by far vjg"nctiguv0"Ecowu"*3;58/3;76+."kp"jgt"oqpwogpvcn"yqtm"Les Chenes, recognises 279 species of Lithocarpus and 430 of Quercus. In addition, there are 3 very small genera containing rare and possibly relict species, namely Trigonobalanus, Co- lombobalanus and Formanodendron0""Vjg"pwodgt"qh"urgekgu"ujg"tgeqipkugf"kp"vjg" other genera is 8 in Fagus, 12 in Nothofagus, 7 in Castanea and 27 in Castanopsis0 Although the actual number of species recognised by different authorities varies, vjgug"Þiwtgu"kpfkecvg"tgncvkxg"urgekgu"tkejpguu0"Qp"vjku"dcuku."qcmu"eqpuvkvwvg"vjg"