Tailed Swallow Hirundo Megaensis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Birds (Aves) of Oromia, Ethiopia – an Annotated Checklist

European Journal of Taxonomy 306: 1–69 ISSN 2118-9773 https://doi.org/10.5852/ejt.2017.306 www.europeanjournaloftaxonomy.eu 2017 · Gedeon K. et al. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License. Monograph urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:A32EAE51-9051-458A-81DD-8EA921901CDC The birds (Aves) of Oromia, Ethiopia – an annotated checklist Kai GEDEON 1,*, Chemere ZEWDIE 2 & Till TÖPFER 3 1 Saxon Ornithologists’ Society, P.O. Box 1129, 09331 Hohenstein-Ernstthal, Germany. 2 Oromia Forest and Wildlife Enterprise, P.O. Box 1075, Debre Zeit, Ethiopia. 3 Zoological Research Museum Alexander Koenig, Centre for Taxonomy and Evolutionary Research, Adenauerallee 160, 53113 Bonn, Germany. * Corresponding author: [email protected] 2 Email: [email protected] 3 Email: [email protected] 1 urn:lsid:zoobank.org:author:F46B3F50-41E2-4629-9951-778F69A5BBA2 2 urn:lsid:zoobank.org:author:F59FEDB3-627A-4D52-A6CB-4F26846C0FC5 3 urn:lsid:zoobank.org:author:A87BE9B4-8FC6-4E11-8DB4-BDBB3CFBBEAA Abstract. Oromia is the largest National Regional State of Ethiopia. Here we present the first comprehensive checklist of its birds. A total of 804 bird species has been recorded, 601 of them confirmed (443) or assumed (158) to be breeding birds. At least 561 are all-year residents (and 31 more potentially so), at least 73 are Afrotropical migrants and visitors (and 44 more potentially so), and 184 are Palaearctic migrants and visitors (and eight more potentially so). Three species are endemic to Oromia, 18 to Ethiopia and 43 to the Horn of Africa. 170 Oromia bird species are biome restricted: 57 to the Afrotropical Highlands biome, 95 to the Somali-Masai biome, and 18 to the Sudan-Guinea Savanna biome. -

Birding Tour to Ghana Specializing on Upper Guinea Forest 12–26 January 2018

Birding Tour to Ghana Specializing on Upper Guinea Forest 12–26 January 2018 Chocolate-backed Kingfisher, Ankasa Resource Reserve (Dan Casey photo) Participants: Jim Brown (Missoula, MT) Dan Casey (Billings and Somers, MT) Steve Feiner (Portland, OR) Bob & Carolyn Jones (Billings, MT) Diane Kook (Bend, OR) Judy Meredith (Bend, OR) Leaders: Paul Mensah, Jackson Owusu, & Jeff Marks Prepared by Jeff Marks Executive Director, Montana Bird Advocacy Birding Ghana, Montana Bird Advocacy, January 2018, Page 1 Tour Summary Our trip spanned latitudes from about 5° to 9.5°N and longitudes from about 3°W to the prime meridian. Weather was characterized by high cloud cover and haze, in part from Harmattan winds that blow from the northeast and carry particulates from the Sahara Desert. Temperatures were relatively pleasant as a result, and precipitation was almost nonexistent. Everyone stayed healthy, the AC on the bus functioned perfectly, the tropical fruits (i.e., bananas, mangos, papayas, and pineapples) that Paul and Jackson obtained from roadside sellers were exquisite and perfectly ripe, the meals and lodgings were passable, and the jokes from Jeff tolerable, for the most part. We detected 380 species of birds, including some that were heard but not seen. We did especially well with kingfishers, bee-eaters, greenbuls, and sunbirds. We observed 28 species of diurnal raptors, which is not a large number for this part of the world, but everyone was happy with the wonderful looks we obtained of species such as African Harrier-Hawk, African Cuckoo-Hawk, Hooded Vulture, White-headed Vulture, Bat Hawk (pair at nest!), Long-tailed Hawk, Red-chested Goshawk, Grasshopper Buzzard, African Hobby, and Lanner Falcon. -

Ghana Nov 2013

Wise Birding Holidays All tours donate to conservation projects worldwide! Trip Report GHANA: Picathartes to Plover Tour Monday 18th Nov. - Tuesday 3rd Dec. 2013 Tour Participants: John Archer, Bob Watts, Graeme Spinks, Peter Alfrey, Nigel & Kath Oram Leaders: Chris Townend & Robert Oteng-Appau HIGHLIGHTS OF TRIP Yellow-headed Picathartes: Whilst sitting quietly in the magical forest, we were wowed by at least 5 different birds as they returned to their roost site. Egyptian Plover: A minimum of 5 adults were seen very well on the White Volta River, along with a very young chick. Confirmed as the first breeding record for Ghana! Rufous-sided Broadbill: A smart male performed admirably as it carried out its acrobatic display flight with amazing mechanical whirring sound. Black Dwarf Hornbill: An amazing 4 different birds seen throughout the tour! Black Bee-Eater: A very understated name for such a fantastically stunning bird! This Yellow-headed Picathartes taken by tour participant Peter Alfrey was one of five birds seen and voted bird of the trip!! WISE BIRDING HOLIDAYS LTD – GHANA: Picathartes to Plover Tour, November 2013 Monday 18th November: Arrive Accra The whole group arrived on time into Accra’s Kotoka Airport. Here, we boarded our spacious air-conditioned coach which was to be our transport for the next 15 days. After about 30 minutes we arrived at our beach hotel and were all soon checked in to our rooms. Everyone was tired, but full of anticipation for our first full days’ birding in Ghana. It was straight to bed for some whereas others were in need of a cool beer before sleep! Tuesday 19th November: Sakumono Lagoon / Winneba Plains It was a relaxed start today with a brief look at the sea before breakfast where the highlights were a few Royal Terns and a Caspian Tern along with our first Copper Sunbird and Laughing Dove in the hotel gardens. -

ETHIOPIA: Birding the Roof of Africa; with Southern Extension a Tropical Birding Set Departure

ETHIOPIA: Birding the Roof of Africa; with Southern Extension A Tropical Birding Set Departure February 7 – March 1, 2010 Guide: Ken Behrens All photos taken by Ken Behrens during this trip ORIENTATION I have chosen to use a different format for this trip report. First, comes a general introduction to Ethiopia. The text of this section is largely drawn from the recently published Birding Ethiopia, authored by Keith Barnes, Christian, Boix and I. For more information on the book, check out http://www.lynxeds.com/product/birding-ethiopia. After the country introduction comes a summary of the highlights of this tour. Next comes a day-by-day itinerary. Finally, there is an annotated bird list and a mammal list. ETHIOPIA INTRODUCTION Many people imagine Ethiopia as a flat, famine- ridden desert, but this is far from the case. Ethiopia is remarkably diverse, and unexpectedly lush. This is the ʻroof of Africaʼ, holding the continentʼs largest and most contiguous mountain ranges, and some of its tallest peaks. Cleaving the mountains is the Great Rift Valley, which is dotted with beautiful lakes. Towards the borders of the country lie stretches of dry scrub that are more like the desert most people imagine. But even in this arid savanna, diversity is high, and the desert explodes into verdure during the rainy season. The diversity of Ethiopiaʼs landscapes supports a parallel diversity of birds and other wildlife, and although birds are the focus of our tour, there is much more to the country. Ethiopia is the only country in Africa that was never systematically colonized, and Rueppell’s Robin-Chat, a bird of the Ethiopian mountains. -

February 2007 2

GHANA 16 th February - 3rd March 2007 Red-throated Bee-eater by Matthew Mattiessen Trip Report compiled by Tour Leader Keith Valentine Top 10 Birds of the Tour as voted by participants: 1. Black Bee-eater 2. Standard-winged Nightjar 3. Northern Carmine Bee-eater 4. Blue-headed Bee-eater 5. African Piculet 6. Great Blue Turaco 7. Little Bee-eater 8. African Blue Flycatcher 9. Chocolate-backed Kingfisher 10. Beautiful Sunbird RBT Ghana Trip Report February 2007 2 Tour Summary This classic tour combining the best rainforest sites, national parks and seldom explored northern regions gave us an incredible overview of the excellent birding that Ghana has to offer. This trip was highly successful, we located nearly 400 species of birds including many of the Upper Guinea endemics and West Africa specialties, and together with a great group of people, we enjoyed a brilliant African birding adventure. After spending a night in Accra our first morning birding was taken at the nearby Shai Hills, a conservancy that is used mainly for scientific studies into all aspects of wildlife. These woodland and grassland habitats were productive and we easily got to grips with a number of widespread species as well as a few specials that included the noisy Stone Partridge, Rose-ringed Parakeet, Senegal Parrot, Guinea Turaco, Swallow-tailed Bee-eater, Vieillot’s and Double- toothed Barbet, Gray Woodpecker, Yellow-throated Greenbul, Melodious Warbler, Snowy-crowned Robin-Chat, Blackcap Babbler, Yellow-billed Shrike, Common Gonolek, White Helmetshrike and Piapiac. Towards midday we made our way to the Volta River where our main target, the White-throated Blue Swallow showed well. -

GHANA MEGA Rockfowl & Upper Guinea Specials Th St 29 November to 21 December 2011 (23 Days)

GHANA MEGA Rockfowl & Upper Guinea Specials th st 29 November to 21 December 2011 (23 days) White-necked Rockfowl by Adam Riley Trip Report compiled by Tour Leader David Hoddinott RBT Ghana Mega Trip Report December 2011 2 Trip Summary Our record breaking trip total of 505 species in 23 days reflects the immense birding potential of this fabulous African nation. Whilst the focus of the tour was certainly the rich assemblage of Upper Guinea specialties, we did not neglect the interesting diversity of mammals. Participants were treated to an astonishing 9 Upper Guinea endemics and an array of near-endemics and rare, elusive, localized and stunning species. These included the secretive and rarely seen White-breasted Guineafowl, Ahanta Francolin, Hartlaub’s Duck, Black Stork, mantling Black Heron, Dwarf Bittern, Bat Hawk, Beaudouin’s Snake Eagle, Congo Serpent Eagle, the scarce Long-tailed Hawk, splendid Fox Kestrel, African Finfoot, Nkulengu Rail, African Crake, Forbes’s Plover, a vagrant American Golden Plover, the mesmerising Egyptian Plover, vagrant Buff-breasted Sandpiper, Four-banded Sandgrouse, Black-collared Lovebird, Great Blue Turaco, Black-throated Coucal, accipiter like Thick- billed and splendid Yellow-throated Cuckoos, Olive and Dusky Long-tailed Cuckoos (amongst 16 cuckoo species!), Fraser’s and Akun Eagle-Owls, Rufous Fishing Owl, Red-chested Owlet, Black- shouldered, Plain and Standard-winged Nightjars, Black Spinetail, Bates’s Swift, Narina Trogon, Blue-bellied Roller, Chocolate-backed and White-bellied Kingfishers, Blue-moustached, -

Bird Survey of South-Eastern Laikipia: Lolldaiga Ranch, Ole Naishu Ranch, Borana Ranch, and Mukogodo Forest Reserve

8 November 2015 Dear All, Recently Nigel Hunter and I went to stay with Tom Butynski on Lolldaiga Hills Ranch. Whilst there we were joined by Paul Benson, and Eleanor Monbiot for the 31st Oct, Chris Thouless joined us on 1st Nov in Mukogodo, and he and Caroline kindly put the three of us up at their house for the nights of 31st Oct and 1st Nov., and for both these dates we enjoyed the company of Lawrence, the bird-guide at Borana Lodge. For our full day on Lolldaiga on 2nd Nov., Paul spent the entire day with us. The more interesting observations follow, but this is far from the full list which exceeded 200 on Lolldaiga alone in spite of the relatively short time we were there. Best for now Brian BIRD SURVEY OF SOUTH-EASTERN LAIKIPIA: LOLLDAIGA RANCH, OLE NAISHU RANCH, BORANA RANCH, AND MUKOGODO FOREST RESERVE ITINERARY 30th Oct 2015 Drove Nairobi to Lolldaiga, birded as far as old Maize Paddock in late afternoon. 31st Oct Drove from TB house out through Ole Naishu Ranch and across Borana arriving at Mukogodo Forest in early afternoon. 1st Nov All day in Mukogodo Forest, and just 5 kilometres down the main descent road in afternoon. 2nd Nov All day on Borana, back across Ole Naishu to Lolldaiga. 3rd Nov All day outing on Lolldaiga to Black Rock, Ngainitu Kopje (North Gate), Sinyai Lugga, and evening near the Monument. 4th Nov Morning on descent road to Main Gate, Lolldaiga and forest along Timau River, leaving 11.15 AM for Nairobi. -

Ethiopian Endemics I 11Th to 29Th January 2014 & Lalibela Historical Extension 29Th January to 1St February 2014

Ethiopian Endemics I 11th to 29th January 2014 & Lalibela Historical Extension th st 29 January to 1 February 2014 Trip report Abyssinian Roller by Markus Lilje Tour leaders: Wayne Jones & Andrew Stainthorpe. Trip report compiled by Wayne Jones RBT Ethiopian Endemics I Trip Report 2014 2 Top 10 birds as voted by participants: 1. Ruspoli’s Turaco 2. Abyssinian Roller 3. Half-collared Kingfisher 4. Fox Kestrel 5. Abyssinian Ground Thrush 6. Nile Valley Sunbird 7. Hartlaub’s Bustard 8. Quailfinch 9. Abyssinian Catbird 10. Abyssinian Woodpecker Tour Summary Our tour kicked off in the grounds of our hotel in Addis Ababa on what was, essentially, an arrival day. Despite its location in the middle of the bustling and chaotic capital city, the gardens yielded a good selection of birds including Wattled Ibis, African Harrier-Hawk, White-collared Pigeon, African Paradise Flycatcher, Brown Parisoma, Dusky Turtle Dove, Abyssinian Thrush, Montane White-eye, Abyssinian Slaty Flycatcher, Brown-rumped Seedeater and Ruppell’s Robin-Chat. Common Cranes by Adam Riley We set out early the following morning so as to arrive at Lake Chelekcheka just after dawn, when the hundreds of Common Cranes that roost there start becoming active amid a cacophony of guttural bugling. With waves of cranes passing over us on their way to forage in the fields, we found plenty of other waterbirds including Northern Shoveler, Spur-winged Goose, Northern Pintail, Eurasian Teal, Greater and Lesser Flamingos, Spur-winged Lapwing, Three-banded Plover, Black-tailed Godwit and Temminck’s Stint. Yellow Wagtails abounded and one of the area’s specials, the tiny and gorgeous Quailfinch, gave excellent views. -

AERC Wplist July 2015

AERC Western Palearctic list, July 2015 About the list: 1) The limits of the Western Palearctic region follow for convenience the limits defined in the “Birds of the Western Palearctic” (BWP) series (Oxford University Press). 2) The AERC WP list follows the systematics of Voous (1973; 1977a; 1977b) modified by the changes listed in the AERC TAC systematic recommendations published online on the AERC web site. For species not in Voous (a few introduced or accidental species) the default systematics is the IOC world bird list. 3) Only species either admitted into an "official" national list (for countries with a national avifaunistic commission or national rarities committee) or whose occurrence in the WP has been published in detail (description or photo and circumstances allowing review of the evidence, usually in a journal) have been admitted on the list. Category D species have not been admitted. 4) The information in the "remarks" column is by no mean exhaustive. It is aimed at providing some supporting information for the species whose status on the WP list is less well known than average. This is obviously a subjective criterion. Citation: Crochet P.-A., Joynt G. (2015). AERC list of Western Palearctic birds. July 2015 version. Available at http://www.aerc.eu/tac.html Families Voous sequence 2015 INTERNATIONAL ENGLISH NAME SCIENTIFIC NAME remarks changes since last edition ORDER STRUTHIONIFORMES OSTRICHES Family Struthionidae Ostrich Struthio camelus ORDER ANSERIFORMES DUCKS, GEESE, SWANS Family Anatidae Fulvous Whistling Duck Dendrocygna bicolor cat. A/D in Morocco (flock of 11-12 suggesting natural vagrancy, hence accepted here) Lesser Whistling Duck Dendrocygna javanica cat. -

OSME List V3.4 Passerines-2

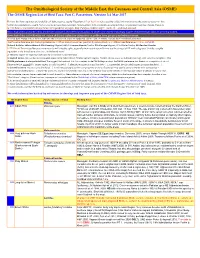

The Ornithological Society of the Middle East, the Caucasus and Central Asia (OSME) The OSME Region List of Bird Taxa: Part C, Passerines. Version 3.4 Mar 2017 For taxa that have unproven and probably unlikely presence, see the Hypothetical List. Red font indicates either added information since the previous version or that further documentation is sought. Not all synonyms have been examined. Serial numbers (SN) are merely an administrative conveninence and may change. Please do not cite them as row numbers in any formal correspondence or papers. Key: Compass cardinals (eg N = north, SE = southeast) are used. Rows shaded thus and with yellow text denote summaries of problem taxon groups in which some closely-related taxa may be of indeterminate status or are being studied. Rows shaded thus and with white text contain additional explanatory information on problem taxon groups as and when necessary. A broad dark orange line, as below, indicates the last taxon in a new or suggested species split, or where sspp are best considered separately. The Passerine Reference List (including References for Hypothetical passerines [see Part E] and explanations of Abbreviated References) follows at Part D. Notes↓ & Status abbreviations→ BM=Breeding Migrant, SB/SV=Summer Breeder/Visitor, PM=Passage Migrant, WV=Winter Visitor, RB=Resident Breeder 1. PT=Parent Taxon (used because many records will antedate splits, especially from recent research) – we use the concept of PT with a degree of latitude, roughly equivalent to the formal term sensu lato , ‘in the broad sense’. 2. The term 'report' or ‘reported’ indicates the occurrence is unconfirmed. -

Species Composition, Relative Abundance and Distribution of the Avian Fauna of Entoto Natural Park and Escarpment, Addis Ababa

SINET: Ethiop. J. Sci., 34(2):113–122, 2011 © College of Natural Sciences, Addis Ababa University, 2011 ISSN: 0379–2897 SPECIES COMPOSITION, RELATIVE ABUNDANCE AND DISTRIBUTION OF THE AVIAN FAUNA OF ENTOTO NATURAL PARK AND ESCARPMENT, ADDIS ABABA Kalkidan Esayas 1 and Afework Bekele 2 1 Department of Natural Science, Gambella Teachers’ Education and Health Science College PO Box 113, Gambella, Ethiopia. E-mail: [email protected] 2 Zological Sciences Program Unit, College of Natural Sciences, Addis Ababa University, PO Box 1176, Addis Ababa Ethiopia. E-mail: [email protected]. ABSTRACT: A study on avian species composition, relative abundance, diversity and distribution at Entoto Natural Park and escarpment was carried out during July 2009 - March 2010. The study area was stratified based on vegetation composition. Four habitat types: forest (rehabilitation and nursery areas), farmland, church compound (St. Mary’s and St. Raguel Churches) and eucalyptus plantation were considered. Point count method was employed for forest habitat and eucalyptus plantation, line-transect method for farmland and total count method was used for the church compound. T-test and ANOVA were applied for analysis of the effect of season and habitats on abundance of species. As a result, 124 avian species belonging to 14 orders and 44 families were identified in the study area during the wet (July, 2009 to October, 2009) and dry season (December, 2009 to March, 2010) surveys. The average temperature and rainfall for wet and dry seasons were 7.5°C and 315 mm and 20.5°C and 9 mm, respectively. During the dry season, highest avian diversity was observed in the farmland habitat (H’=3.73), followed by the forest (H’=2.92), whereas during the wet season, highest avian diversity was observed in the forest habitat (H’=3.98), followed by church compound (H’=3.25). -

Version 2014-04-28 Attached Is the Dynamic1 List of Migratory Landbird

African-Eurasian Migratory Landbirds Action Plan Annex 3: Species Lists Version 2014-04-28 Attached is the dynamic1 list of migratory landbird species that occur within the African Eurasian region according to the following definition: 1. Migratory is defined as those species recorded within the IUCN Species Information Service (SIS) and BirdLife World Bird Database (WBDB) as ‘Full Migrant’, i.e. species which have a substantial (>50%) proportion of the global population which migrates: - with the addition of Great Bustard Otis tarda which is listed on CMS Appendix I and is probably erroneously recorded as an altitudinal migrant within SIS and the WBDB - with the omission of all single-country endemic migrants, in order to conform with the CMS definition of migratory which requires a species to ‘cross one or more national jurisdictional boundaries,’; in reality this has meant the removal of only one species, Madagascar Blue-pigeon Alectroenas madagascariensis. However, it should be noted that removing single-country endemics is not strictly analogous with omitting species that do not cross political borders. It is quite possible for a migratory species whose range extends across multiple countries to contain no populations that actually cross national boundaries as part of their regular migration. 2. African-Eurasian is defined as Africa, Europe (including all of the Russian Federation and excluding Greenland), the Middle East, Central Asia, Afghanistan, and the Indian sub-continent. 3. Landbird is defined as those species not recorded in SIS and the WBDB as being seabirds, raptors or waterbirds, except for the following waterbird species that are recorded as not utilising freshwater habitats: Geronticus eremita, Geronticus calvus, Burhinus oedicnemus, Cursorius cursor and Tryngites subruficollis.