7 -·~·· :1 ·.·.~

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

High Diversity of Fungi Recovered from the Roots of Mature Tanoak (Lithocarpus Densiflorus) in Northern California

1380 High diversity of fungi recovered from the roots of mature tanoak (Lithocarpus densiflorus)in northern California S.E. Bergemann and M. Garbelotto Abstract: We collected mature tanoak (Lithocarpus densiflorus (Hook. & Arn.) Rehder) roots from five stands to charac- terize the relative abundance and taxonomic richness of root-associated fungi. Fungi were identified using polymerase chain reaction (PCR), cloning, and sequencing of internal transcribed spacer (ITS) and 28S rDNA. A total of 382 cloned PCR inserts were successfully sequenced and then classified into 119 taxa. Of these taxa, 82 were basidiomycetes, 33 were ascomycetes, and 4 were zygomycetes. Thirty-one of the ascomycete sequences were identified as Cenococcum geo- philum Fr. with overall richness of 22 ITS types. Other ascomycetes that form mycorrhizal associations were identified in- cluding Wilcoxina and Tuber as well as endophytes such as Lachnum, Cadophora, Phialophora, and Phialocephela. The most abundant mycorrhizal groups were Russulaceae (Lactarius, Macowanites, Russula) and species in the Thelephorales (Bankera, Boletopsis, Hydnellum, Tomentella). Our study demonstrates that tanoak supports a high diversity of ectomycor- rhizal fungi with comparable species richness to that observed in Quercus root communities. Key words: Cenoccocum geophilum, community, dark septate endophytes, ectomycorrhiza, species richness. Re´sume´ : Les auteurs ont pre´leve´ des racines de Lithocarpus densiflorus (Hook. & Arn.) Rehder) dans cinq peuplements, afin de caracte´riser l’abondance relative et la richesse taxonomique des champignons associe´sa` ses racines. On a identifie´ les champignons a` l’aide du PCR, par clonage et se´quenc¸age de l’ITS et du 28S rADN. On a se´quence´ avec succe`s 382 segments clone´s par PCR avant de les classifier en 119 taxons. -

Blood Mushroom

Bleeding-Tooth Fungus Hydnellum Peckii Genus: Hydnellum Family: Bankeraceae Also known as: Strawberries and Cream Fungus, Bleeding Hydnellum, Red-Juice Tooth, or Devil’s Tooth. If you occasionally enjoy an unusual or weird sight in nature, we have one for you. Bleeding-Tooth Fungus fits this description with its strange colors and textures. This fungus is not toxic, but it is considered inedible because of its extremely bitter taste. Hydnoid species of fungus produce their spores on spines or “teeth”; these are reproductive structures. This fungus “bleeds” bright red droplets down the spines, so that it looks a little like blood against the whitish fungus. This liquid actually has an anticoagulant property similar to the medicine heparin; it keeps human or animal blood from clotting. This fungus turns brown with age. Bloody-Tooth Fungus establishes a relationship with the roots of certain trees, so you will find it lower down on the tree’s trunk. The fungus exchanges the minerals and amino acids it has extracted from the soil with its enzymes, for oxygen and carbon within the host tree that allow the fungus to flourish. It’s a great partnership that benefits both, called symbiosis. The picture above was taken at Kings Corner at the pine trees on the west side of the property. It was taken in early to mid-autumn. This part of the woods is moist enough to grow some really beautiful mushrooms and fungi. Come and see—but don’t touch or destroy. Fungi should be respected for the role they play in the woods ecology. -

Biodiversity Action Plan for Hampshire

BIODIVERSITY ACTION PLAN FOR HAMPSHIRE VOLUME TWO HAMPSHIRE BIODIVERSITY PARTNERSHIP HAMPSHIRE BIODIVERSITY PARTNERSHIP BIODIVERSITY Basingstoke and Deane Borough Council Hampshire Business Environment Forum ACTION British Trust for Conservation Volunteers Hampshire County Council PLAN FOR HAMPSHIRE Butterfly Conservation Hampshire Ornithological Society Country Landowners Association Hampshire Wildlife Trust Countryside Agency Hart District Council East Hampshire District Council Havant Borough Council Eastleigh Borough Council Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food English Nature Ministry of Defence Environment Agency National Farmers Union Fareham Borough Council New Forest District Council Farming and Rural Conservation Agency Portsmouth City Council Farming and Wildlife Advisory Group Royal Society for the Protection of Birds Forest Enterprise Rushmoor Borough Council Forestry Commission Southampton City Council The Game Conservancy Trust Test Valley Borough Council Gosport Borough Council Winchester City Council Government Office for the South East Hampshire Association of Parish and Town Councils The following organisations have contributed to the cost of producing this Plan: Hampshire County Council, Environment Agency, Hampshire Wildlife Trust and English Nature. Individual action plans have been prepared by working groups involving many organisations and individuals - principal authors are acknowledged in each plan. The preparation of Habitat Action Plans has been co-ordinated by Hampshire County Council, and Species -

Phellodon Secretus (Basidiomycota ), a New Hydnaceous Fungus.From Northern Pine Woodlands

Karstenia 43: 37--44, 2003 Phellodon secretus (Basidiomycota ), a new hydnaceous fungus.from northern pine woodlands TUOMO NIEMELA, JUHA KJNNUNEN, PERTII RENVALL and DMITRY SCHIGEL NIEMELA, T. , KINNUNEN, J. , RENVALL, P. & SCHIGEL, D. 2003: Phellodon secretus (Basidiomycota), a new hydnaceous fungus from northern pine woodlands. Karstenia 43: 37-44. 2003. Phellodon secretus Niemela & Kinnunen (Basidiomycota, Thelephorales) resembles Phellodon connatus (Schultz : Fr.) P. Karst., but differs in havi ng a thinner stipe, cottony soft pileus, and smaller and more globose spores. Its ecology is peculiar: it is found in dry, old-growth pine woodlands, growing in sheltered places under strongly decayed trunks or rootstocks of pine trees, where there is a gap of only a few centim eters between soil and wood. Basidiocarps emerge from humus as needle-like, ca. I mm thick, black stipes, and the pileus unfolds only after the stipe tip has contacted the overhanging wood. In its ecology and distribution the species resembles Hydnellum gracilipes (P. Karst.) P. Karst. It seems to be extremely rare, found in Northern boreal and Middle boreal vegetation zones, in areas with fairly continental climate. Key words: Aphyllophorales, Phellodon, hydnaceous fungi, taxonomy Tuomo Niemela, Juha Kinnunen & Dmitry Schigel, Finnish Museum of Natural His tory, Botanical Museum, P.O. Box 7, FIN-00014 University of Helsinki, Finland Pertti Renvall, Kuopio Natural History Museum, Myhkyrinkatu 22, FIN-70100 Kuo pio, Finland Introduction Virgin pine woodlands of northern Europe make a eventually dying while standing. Such dead pine specific environment for fungi. The barren sandy trees may keep standing for another 200-500 soil, spaced stand of trees and scanty lower veg years, losing their bark and thinner branches: in etation result in severe drought during sunny this way the so-called kelo trees develop, com summer months, in particular because such wood mon and characteristic for northern old-growth lands are usually situated on exposed hillsides, pine woodlands. -

Taxonomy and Systematics of Thelephorales – Glimpses Into Its Hidden Hyperdiversity

Taxonomy and Systematics of Thelephorales – Glimpses Into its Hidden Hyperdiversity Sten Svantesson 2020 UNIVERSITY OF GOTHENBURG Faculty of Science Department of Biological and Environmental Sciences Opponent Prof. Annemieke Verbeken Examiner Prof. Bengt Oxelman Supervisors Associate Prof. Ellen Larsson & Profs. Karl-Henrik Larsson, Urmas Kõljalg Associate Profs. Tom W. May, R. Henrik Nilsson © Sten Svantesson All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without written permission. Svantesson S (2020) Taxonomy and systematics of Thelephorales – glimpses into its hidden hyperdiversity. PhD thesis. Department of Biological and Environmental Sciences, University of Gothenburg, Gothenburg, Sweden. Många är långa och svåra att fånga Cover image: Pseudotomentella alobata, a newly described species in the Pseudotomentella tristis group. Många syns inte men finns ändå Många är gula och fula och gröna ISBN print: 978-91-8009-064-3 Och sköna och röda eller blå ISBN digital: 978-91-8009-065-0 Många är stora som hus eller så NMÄ NENMÄRK ANE RKE VA ET SV T Digital version available at: http://hdl.handle.net/2077/66642 S Men de flesta är små, mycket små, mycket små Trycksak Trycksak 3041 0234 – Olle Adolphson, från visan Okända djur Printed by Stema Specialtryck AB 3041 0234 © Sten Svantesson All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without written permission. Svantesson S (2020) Taxonomy and systematics of Thelephorales – glimpses into its hidden hyperdiversity. PhD thesis. Department of Biological and Environmental Sciences, University of Gothenburg, Gothenburg, Sweden. Många är långa och svåra att fånga Cover image: Pseudotomentella alobata, a newly described species in the Pseudotomentella tristis group. -

Om Förekomsten Av Hydnellum Cumulatum Och H. Scrobiculatum I Sverige

Svensk Mykologisk Tidskrift 30 (2): 3-8, 2009 SVAMPPRESENTATION Om förekomsten av Hydnellum cumulatum och H. scrobiculatum i Sverige EEF ARNOLDS Abstract On the occurrence of Hydnellum cumulatum and H. scrobiculatum in Sweden. The stipitate hydnoid fungus Hydnellum cumulatum, originally described from Canada, is re- ported as new to Sweden. It was collected in 2007 in two old stands of Picea abies (Tuskö- sundet and Plogmyren) in the coastal region of eastern-central Sweden in the province of Uppland near Östhammar. The species had been found there before and provisionally identified as Hydnellum scrobiculatum. Two other Swedish herbarium collections under the latter name also proved to belong to H. cumulatum. A full description in Swedish and English of that species is provided. The differences between H. scrobiculatum and H. concrescens are discussed. Spore size and ornamentation are the most important discriminating characters, but they are probably also recognisable in the field on differences in pileus surface and smell. More research is needed to confirm this. The conspecificity between European and American collections of H. cumulatum is discussed. The identity of H. scrobiculatum and its oc- currence in Sweden are discussed as well. It is concluded that this taxon may be a phantom species, falling within the variation of H. concrescens, but more research is needed including a renewed study of the neotype collected near Femsjö, Sweden. Inledning auratile, Sarcodon fuligineoviolaceus, S. mar- Mot bakgrund av vårt intresse för taxonomi, tioflavus och S. versipellis. För oss som är vana ekologi och bevarandefrågor kring taggsvam- vid Nederländernas fattiga barrskogsplanteringar par (Arnolds 1989, 2003) blev min kollega var de uppländska sandiga tallskogarna och ört- Rob Chrispijn och jag själv inbjudna av orga- rika granskogarna förbluffande rika och föreföll nisatören Johan Nitare att delta i en workshop representera ett ”mykologiskt himmelrike på jor- i norra Uppland i september 2007. -

Highland Biodiversity Action Plan 2010

HIGHLAND BAP March 2010 Foreword Facal-toisich This Biodiversity Action Plan has been drawn up by Highland Council on behalf of the Highland Biodiversity Partnership. The Partnership is made up of representatives of around 30 local groups and organisations committed to understanding, safeguarding, restoring and celebrating biodiversity within Highland. Our purpose is to provide guidance and support to the existing network of Local Biodiversity Groups, and to make progress on the key strategic biodiversity issues in the Highlands. It is this last point that we hope to address through this Plan. The Plan lists the key issues that have been brought to our attention since the Partnership started in 2005, and proposes a range of future actions or projects that we’d like to undertake in the next three years. We have made progress on nine of the ten strategic issues that were identified in the 2006 Highland BAP. This Plan proposes 24 new projects, each with simple, measurable targets and an identifiable lead partner. It is perhaps fitting that this Plan is being launched in 2010, the International Year of Biodiversity and understandably, a desire to raise awareness building on all the good work undertaken to date features strongly in it. We are of course bound by limits on the budget and resources that our partners can muster in these difficult times, but nonetheless we are confident that we can achieve a lot by working together and planning ahead. Please visit our website www.highlandbiodiversity.com for further information and an electronic -

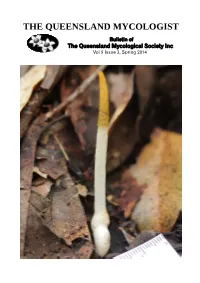

A Most Mysterious Fungus 14

THE QUEENSLAND MYCOLOGIST Bulletin of The Queensland Mycological Society Inc Vol 9 Issue 3, Spring 2014 The Queensland Mycological Society ABN No 18 351 995 423 Internet: http://qldfungi.org.au/ Email: info [at] qldfungi.org.au Address: PO Box 5305, Alexandra Hills, Qld 4161, Australia QMS Executive Society Objectives President The objectives of the Queensland Mycological Society are to: Frances Guard 07 5494 3951 1. Provide a forum and a network for amateur and professional info[at]qldfungi.org.au mycologists to share their common interest in macro-fungi; Vice President 2. Stimulate and support the study and research of Queensland macro- Patrick Leonard fungi through the collection, storage, analysis and dissemination of 07 5456 4135 information about fungi through workshops and fungal forays; patbrenda.leonard[at]bigpond.com 3. Promote, at both the state and federal levels, the identification of Secretary Queensland’s macrofungal biodiversity through documentation and publication of its macro-fungi; Ronda Warhurst 4. Promote an understanding and appreciation of the roles macro-fungal info[at]qldfungi.org.au biodiversity plays in the health of Queensland ecosystems; and Treasurer 5. Promote the conservation of indigenous macro-fungi and their relevant Leesa Baker ecosystems. Minutes Secretary Queensland Mycologist Ronda Warhurst The Queensland Mycologist is issued quarterly. Members are invited to submit short articles or photos to the editor for publication. Material can Membership Secretary be in any word processor format, but not PDF. The deadline for Leesa Baker contributions for the next issue is 1 November 2014, but earlier submission is appreciated. Late submissions may be held over to the next edition, Foray Coordinator depending on space, the amount of editing required, and how much time Frances Guard the editor has. -

Bankera Violascens and Sarcodon Versipellis

C z e c h m y c o l . 49 (1), 1996 Notes on two hydnums - Bankera violascens and Sarcodon versipellis P e t r H r o u d a Department of Systematic Botany and Geobotany, Masaryk University, Kotlářská 2, 61137 Brno, Czech Republic Hrouda P. (1996): Notes on two hydnums - Bankera violascens and Sarcodon versipellis. - Czech Mycol. 49: 35-39 This article deals with two questions concerning to hydnaceous fungi. I do not accept the name Bankera cinerea (Bull.: Fr.) Rauschert for Bankera violascens (Alb. et Schw.: Fr.) Pouz. The reason is that Bulliard’s illustration of Hydnum cinereum, on which Rauschert based his combination, in my opinion does not show a species of the genus Bankera. The characters, on which this statement is based, are given. The specimens of Sarcodon balsamiodorus Pouz. in schaedis from herbaria (PRM, BRA) belong, also according to the description of fresh material, to Sarcodon versipellis (Fr.) Quel. Key words: Combination, Bankera cinerea, Bulliard’s illustration, exsiccates, Sarcodon balsamiodorus. Hrouda P. (1996): Poznámky ke dvěma lošákům - bělozubu nafialovělému a lošáku balzámovému. - Czech Mycol. 49: 35-39 článek komentuje dva otazníky vyvstavší při studiu lošáků. Neakceptuji jméno Bankera cinerea (Bull.: Fr.) Rauschert pro Bankera violascens (Alb. et Schw.: Fr.) Pouz., neboť exempláře Hydnum cinereum na Bulliardově ilustraci, na kterých Rauschert zakládá svou kombinaci, podle mého názoru nejsou jedinci rodu Bankera. Podávám popis znaků, na kterých zakládám své tvrzení. Položky Sarcodon balsamiodorus Pouz. in schaedis, uložené v pražském (PRM) a bratislav ském (BRA) herbáři, patří podle popisu čerstvého materiálu k Sarcodon versipellis (Fr.) Quél. -

Red List of Fungi for Great Britain: Bankeraceae, Cantharellaceae

Red List of Fungi for Great Britain: Bankeraceae, Cantharellaceae, Geastraceae, Hericiaceae and selected genera of Agaricaceae (Battarrea, Bovista, Lycoperdon & Tulostoma) and Fomitopsidaceae (Piptoporus) Conservation assessments based on national database records, fruit body morphology and DNA barcoding with comments on the 2015 assessments of Bailey et al. Justin H. Smith†, Laura M. Suz* & A. Martyn Ainsworth* 18 April 2016 † Deceased 3rd March 2014. (13 Baden Road, Redfield, Bristol BS5 9QE) * Jodrell Laboratory, Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, Surrey TW9 3AB Contents 1. Foreword............................................................................................................................ 3 2. Background and Introduction to this Review .................................................................... 4 2.1. Taxonomic scope and nomenclature ......................................................................... 4 2.2. Data sources and preparation ..................................................................................... 5 3. Methods ............................................................................................................................. 7 3.1. Rationale .................................................................................................................... 7 3.2. Application of IUCN Criterion D (very small or restricted populations) .................. 9 4. Results: summary of conservation assessments .............................................................. 16 5. Results: -

List of UK BAP Priority Fungi Species (Including Lichens) (2007)

UK Biodiversity Action Plan List of UK BAP Priority Fungi Species (including lichens) (2007) For more information about the UK Biodiversity Action Plan (UK BAP) visit https://jncc.gov.uk/our-work/uk-bap/ List of UK BAP Priority Fungi Species (including lichens) (2007) A list of UK BAP priority fungi species (including lichens), created between 1995 and 1999, and subsequently updated in response to the Species and Habitats Review Report, published in 2007, is provided in the table below. The table also provides details of the species' occurrences in the four UK countries, and describes whether the species was an 'original' species (on the original list created between 1995 and 1999), or was added following the 2007 review. All original species were provided with Species Action Plans (SAPs), species statements, or are included within grouped plans or statements, whereas there are no published plans for the species added in 2007. Scientific names and commonly used synonyms derive from the Nameserver facility of the UK Species Dictionary, which is managed by the Natural History Museum. Scientific name Common name Taxon England Scotland Wales Northern Original UK Ireland BAP species? Acarospora lichen Y N N N subrufula Alectoria lichen N Y N N Yes – SAP ochroleuca Amanita friabilis Fragile Amanita fungus Y N Y N (non- lichenised) Anaptychia ciliaris lichen Y Y Y N subsp. ciliaris Armillaria ectypa Marsh Honey fungus Y Y Y Y Yes – SAP Fungus (non- lichenised) Arthonia anglica lichen Y N N N Arthonia atlantica lichen Y Y Y N Arthonia lichen -

June 1997 ISSN 0541 -4938 Newsletter of the Mycological Society of America

Vol. 48(3) June 1997 ISSN 0541 -4938 Newsletter of the Mycological Society of America About This lssue This issue of Inoculum is devoted mainly to the business of the society-the ab- stracts and schedule for the Annual Meeting are included as well as the minutes of the mid-year meeting of the Executive Committee. Remember Inoculum as you prepare for the trip to Montreal. Copy for the next issue is due July 3, 1997. In This lssue Mycology Online ................... 1 Mycology Online MSA Official Business .......... 2 Executive Committee MSA Online Minutes ................................ 3 Visit the MSA Home Page at <http://www.erin.utoronto.ca~soc/msa~>.Members Mycological News .................. 5 can use the links from MSA Home Page to access MSA resources maintained on 1996 Foray Results .............. 6 other servers. Calendar of Events .............. 10 MSAPOST is the new MSA bulletin board service. To subscribe to MSAPOST, Mycological Classifieds ...... 12 send an e-mail message to <[email protected]>.The text of the mes- Abstracts ............................... 17 sage should say subscribe MSAPOST Your Name. Instructions for using MSAPOST are found on the MSA Home Page and in Inoculum 48(1): 5. Change of Address .............. 13 Fungal Genetics The abstracts for the plenary sessions and poster sessions from the 19' Fungal Ge- netics Conference at Asilomar are now available on-line at the FGSC web site <www.kumc.edu/researchlfgsc/main.html>.They can be found either by following Important Dates the Asilomar information links, or by going directly here: <http://www.kumc.edu July 3, 1997 - Deadline for /research/fgsc/asilomar/fgcabs97.html>.[Kevin McCluskey].