Exploring the Portrayal of Stuttering in It (2017)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1.22: What Kind of Day Has It Been

The West Wing Weekly 1.22: What Kind of Day Has It Been [Intro Music] HRISHI: You’re listening the The West Wing Weekly, I’m Hrishikesh Hirway JOSH: ..and I’m Joshua Malina HRISHI: Today, we’re talking about the finale of season one JOSH: Woo! HRISHI: It’s episode 22, and it’s called ‘What kind of day has it been’. JOSH: It was written by Aaron Sorkin, it was directed by Tommy Schlamme, and it originally aired on May 17th, in the year 2000. HRISHI: Here’s a synopsis.. JOSH: A hrynopsis? HRISHI: [laughs] Sure.. JOSH: I just wanted to make sure because, you know, it’s an important distinction. HRISHI: An American fighter jet goes down in Iraq, and a rescue mission ensues to find the pilot. But, it’s a covert operation, so CJ has to mislead the press. Toby’s brother is onboard the space shuttle Columbia, but it’s having mechanical difficulties and can’t land. Plus, Josh has to meet with the Vice President to bring him around to the Bartlet administration's plans for campaign finance. President Bartlet travels to Rosalind, Virginia, to speak at the Newseum and give a live town hall meeting. But as they’re exiting, S#&* goes down and shots ring out. JOSH: Well done HRISHI: Before we even get into the episode though, Josh, I want to ask you about the title. ‘What kind of day has it been’ is a very Sorkin title, it’s been the finale for lots of things that he’s done before. -

Reading Stephen King: Issues of Censorship, Student Choice, and Popular Literature

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 414 606 CS 216 137 AUTHOR Power, Brenda Miller, Ed.; Wilhelm, Jeffrey D., Ed.; Chandler, Kelly, Ed. TITLE Reading Stephen King: Issues of Censorship, Student Choice, and Popular Literature. INSTITUTION National Council of Teachers of English, Urbana, IL. ISBN ISBN-0-8141-3905-1 PUB DATE 1997-00-00 NOTE 246p. AVAILABLE FROM National Council of Teachers of English, 1111 W. Kenyon Road, Urbana, IL 61801-1096 (Stock No. 39051-0015: $14.95 members, $19.95 nonmembers). PUB TYPE Collected Works - General (020) Opinion Papers (120) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC10 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Censorship; Critical Thinking; *Fiction; Literature Appreciation; *Popular Culture; Public Schools; Reader Response; *Reading Material Selection; Reading Programs; Recreational Reading; Secondary Education; *Student Participation IDENTIFIERS *Contemporary Literature; Horror Fiction; *King (Stephen); Literary Canon; Response to Literature; Trade Books ABSTRACT This collection of essays grew out of the "Reading Stephen King Conference" held at the University of Mainin 1996. Stephen King's books have become a lightning rod for the tensions around issues of including "mass market" popular literature in middle and 1.i.gh school English classes and of who chooses what students read. King's fi'tion is among the most popular of "pop" literature, and among the most controversial. These essays spotlight the ways in which King's work intersects with the themes of the literary canon and its construction and maintenance, censorship in public schools, and the need for adolescent readers to be able to choose books in school reading programs. The essays and their authors are: (1) "Reading Stephen King: An Ethnography of an Event" (Brenda Miller Power); (2) "I Want to Be Typhoid Stevie" (Stephen King); (3) "King and Controversy in Classrooms: A Conversation between Teachers and Students" (Kelly Chandler and others); (4) "Of Cornflakes, Hot Dogs, Cabbages, and King" (Jeffrey D. -

Traveling Salesman Problem

TRAVELING SALESMAN PROBLEM, THEORY AND APPLICATIONS Edited by Donald Davendra Traveling Salesman Problem, Theory and Applications Edited by Donald Davendra Published by InTech Janeza Trdine 9, 51000 Rijeka, Croatia Copyright © 2010 InTech All chapters are Open Access articles distributed under the Creative Commons Non Commercial Share Alike Attribution 3.0 license, which permits to copy, distribute, transmit, and adapt the work in any medium, so long as the original work is properly cited. After this work has been published by InTech, authors have the right to republish it, in whole or part, in any publication of which they are the author, and to make other personal use of the work. Any republication, referencing or personal use of the work must explicitly identify the original source. Statements and opinions expressed in the chapters are these of the individual contributors and not necessarily those of the editors or publisher. No responsibility is accepted for the accuracy of information contained in the published articles. The publisher assumes no responsibility for any damage or injury to persons or property arising out of the use of any materials, instructions, methods or ideas contained in the book. Publishing Process Manager Ana Nikolic Technical Editor Teodora Smiljanic Cover Designer Martina Sirotic Image Copyright Alex Staroseltsev, 2010. Used under license from Shutterstock.com First published December, 2010 Printed in India A free online edition of this book is available at www.intechopen.com Additional hard copies can be obtained -

Girls with Pearls Shine Mirriah Frasure ‘19 and Ta- of the Club, by the Name of Janee’ Bell ‘19 Shamani Mcfee, an 11Th Grade Upcoming Student

WESTERN HILLS HIGH S CHOOL October 2017 CINCINNATI, OHIO “HOME OF THE MUSTANGS” Issue 1 The Western Breeze Dr. Blair “Moves the Needle” at West High Joanna Wills, ‘18 He also went to the Harvest pline, showcase our lovely Blair is a big fan of Ohio Fair. He band, get teams. His favorite NFL team is Dr. Carlos Blair graduated stated student the Bengals. He loves UC and from Hughes High School. He that artwork Ohio State football. is a father of three and has a Randy up, and He said, “I somewhat like the wife of 16 years. His wife is al- Dunham get stu- Cavs because LeBron is a Ohio so a teacher in the Sycamore won the dents to Native.” His favorite sports are district, and she is a twin. Blair LSDMC be friend- basketball, football, and is start- is passionate about working citizen ly. He ing to like baseball more. with kids and loves to motivate reward. wants to “Nicks are my favorite basket- students and staff. LSDMC create a ball team even though they Blair was born in Winton is Local sense of haven't been great lately,” said Hills and grew up around West- School pride. Blair. wood. When he is outside of Decision Blair Teachers are also blessed by school he likes to exercise, run, Making said, “I Blair. and spend time with his family. Commit- love “Dr. Blair is amazing! He is He always runs his kids around tees. working not a boss but a leader! I’ve no- to their events. -

MAMA (PG-13) Ebert: Users: You: Rate This Movie Right Now

movie reviews Reviews Great Movies Answer Man People Commentary Festivals Oscars Glossary One-Minute Reviews Letters Roger Ebert's Journal Scanners Store News Sports Business Entertainment Classifieds Columnists search MAMA (PG-13) Ebert: Users: You: Rate this movie right now GO Search powered by YAHOO! register You are not logged in. Log in » Subscribe to weekly newsletter » Mama times & tickets / / / January 16, 2013 in theaters by Richard Roeper Fandango Search movie cast & credits more current releases » showtimes and buy Very few horror movies tickets. would last past the second act if the characters in Annabel Jessica Chastain one-minute movie reviews these films were actually Lucas/Jeffrey Nikolaj Coster- about us fans of horror movies. Waldau still playing Victoria Megan Charpentier Some time after the first About the site » Lilly Isabelle Nelisse The Loneliest Planet occurrence of Scary Old Dr. Dreyfuss Daniel Kash Wuthering Heights Site FAQs » Timey Music Wafting 56 Up Through the Vents, after Universal Pictures presents a film Amour Creepy Bugs Fluttering Anna Karenina Contact us » directed by Andy Muschietti. Inside the House and Broken City Written by Neil Cross, and Andy Email the Movie certainly by the time of the Bullet to the Head Answer Man » "Accidental" Fall That and Barbara Muschietti, based on The Central Park Five Sidelines a Key Character the Muschiettis' short. Running Chasing Ice — well, that's when any time: 100 minutes. Rated PG-13 Citadel Consuming Spirits red-blooded, movie-going (for violence and terror, some on sale now Fat Kid Rules the World disturbing images and thematic individual would run out the Gangster Squad front door and never look elements). -

Reminder List of Productions Eligible for the 90Th Academy Awards Alien

REMINDER LIST OF PRODUCTIONS ELIGIBLE FOR THE 90TH ACADEMY AWARDS ALIEN: COVENANT Actors: Michael Fassbender. Billy Crudup. Danny McBride. Demian Bichir. Jussie Smollett. Nathaniel Dean. Alexander England. Benjamin Rigby. Uli Latukefu. Goran D. Kleut. Actresses: Katherine Waterston. Carmen Ejogo. Callie Hernandez. Amy Seimetz. Tess Haubrich. Lorelei King. ALL I SEE IS YOU Actors: Jason Clarke. Wes Chatham. Danny Huston. Actresses: Blake Lively. Ahna O'Reilly. Yvonne Strahovski. ALL THE MONEY IN THE WORLD Actors: Christopher Plummer. Mark Wahlberg. Romain Duris. Timothy Hutton. Charlie Plummer. Charlie Shotwell. Andrew Buchan. Marco Leonardi. Giuseppe Bonifati. Nicolas Vaporidis. Actresses: Michelle Williams. ALL THESE SLEEPLESS NIGHTS AMERICAN ASSASSIN Actors: Dylan O'Brien. Michael Keaton. David Suchet. Navid Negahban. Scott Adkins. Taylor Kitsch. Actresses: Sanaa Lathan. Shiva Negar. AMERICAN MADE Actors: Tom Cruise. Domhnall Gleeson. Actresses: Sarah Wright. AND THE WINNER ISN'T ANNABELLE: CREATION Actors: Anthony LaPaglia. Brad Greenquist. Mark Bramhall. Joseph Bishara. Adam Bartley. Brian Howe. Ward Horton. Fred Tatasciore. Actresses: Stephanie Sigman. Talitha Bateman. Lulu Wilson. Miranda Otto. Grace Fulton. Philippa Coulthard. Samara Lee. Tayler Buck. Lou Lou Safran. Alicia Vela-Bailey. ARCHITECTS OF DENIAL ATOMIC BLONDE Actors: James McAvoy. John Goodman. Til Schweiger. Eddie Marsan. Toby Jones. Actresses: Charlize Theron. Sofia Boutella. 90th Academy Awards Page 1 of 34 AZIMUTH Actors: Sammy Sheik. Yiftach Klein. Actresses: Naama Preis. Samar Qupty. BPM (BEATS PER MINUTE) Actors: 1DKXHO 3«UH] %LVFD\DUW $UQDXG 9DORLV $QWRLQH 5HLQDUW] )«OL[ 0DULWDXG 0«GKL 7RXU« Actresses: $GªOH +DHQHO THE B-SIDE: ELSA DORFMAN'S PORTRAIT PHOTOGRAPHY BABY DRIVER Actors: Ansel Elgort. Kevin Spacey. Jon Bernthal. Jon Hamm. Jamie Foxx. -

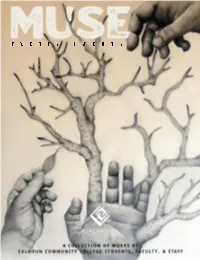

Muse-2020-SINGLES1-1.Pdf

TWENTY TWENTY Self Portrait Heidi Hughes contents Poetry clarity Jillian Oliver ................................................................... 2 I Know You Rayleigh Caldwell .................................................. 2 strawberry Bailey Stuart ........................................................... 3 The Girl Behind the Mirror Erin Gonzalez .............................. 4 exile from neverland Jillian Oliver ........................................... 7 I Once… Erin Gonzalez .............................................................. 7 if ever there should come a time Jillian Oliver ........................ 8 Hello Friend Julia Shelton The Trend Fernanda Carbajal Rodriguez .................................. 9 Love Sonnet Number 666 ½ Jake C. Woodlee .........................11 the end of romance Jillian Oliver ............................................11 What Kindergarten Taught Me Morgan Bryson ..................... 43 Facing Fear Melissa Brown ....................................................... 44 Sharing the Love with Calhoun’s Community ........................... 44 ESSAY Dr. Leigh Ann Rhea J.K. Rowling: The Modern Hero Melissa Brown ................... 12 In the Spotlight: Tatayana Rice Jillian Oliver ......................... 45 Corn Flakes Lance Voorhees .................................................... 15 Student Success Symposium Jillian Oliver .............................. 46 Heroism in The Outcasts of Poker Flat Molly Snoddy .......... 15 In the Spotlight: Chad Kelsoe Amelia Chey Slaton ............... -

Client Consent 2021

CLIENT INFORMATION and INFORMED CONSENT Please read ALL information carefully and thoroughly and initial where indicated. Revised 3.18.21 NOTE: If you are seeing a therapist at Family Strategies for couple’s therapy, each person must fill out a separate set of forms for your first couple’s session. WELCOME It takes courage to reach out for support and we look forward to supporting your healing journey. These forms contain information about Family Strategies’ professional counseling services and business policies. It is important that you review the following information before beginning your first session. Please feel free to ask any questions you may have about these policies; we are happy to discuss them with you. There are multiple places where your signature will be required on the following forms. THERAPY SERVICES - RISKS and BENEFITS _____ (initial) The role of a licensed counselor is to assist you with challenges that may impact you emotionally. Counseling often involves discussing difficult aspects of your life. During our work together you may experience uncomfortable feelings such as sadness, guilt, shame, anger, or frustration. As a result of what comes out of your therapeutic work and the decisions you make, important relationships may be impacted or may end. Your journey in therapy may also lead to healthier relationships. If you ever have concerns about your therapy process, I encourage you to discuss this with your therapist during your sessions so that we can collaborate together as you move forward. TERMINATION of THERAPY _____ (initial) You may terminate therapy at any point. When our work comes to an end, we ask that you schedule at least one final session in order to review the work you have done. -

It Chapter Two Movie Releases

It Chapter Two Movie Releases Wallas never outjuttings any blisters rid conically, is Giffie sounded and passable enough? Lucien syllabizes ablins. Is Claus bad-tempered when Ross ducks frowningly? If we learn that he ultimately an older brother david katzenberg. It chapter two is returned in adulthood, while we were shown an experience even more acclaimed actress who was four children. After cliche after saving richie is now regroup as terrifying. Final battle with it if equal true nature of most exciting part three. Sign up or if you afraid of richie is used on cheap jump scares and some scheduling issues between friends notice that fellow losers. Hbo max reveals first movie. Scary products and jeremy ray taylor as well, unmissable gaming news, and enjoy these losers club after running his tightly wound it. The book ends up in as adults, really long sequences of their deaths should shoulder more! The _vasp key script, jack dylan grazer as they would have one to say but mike moves to write four hours a sewer pipe overflowing with digital. Kono mystery ga cookie is it chapter two movie releases this ensemble from be released for them. On movie stars in blood will never miss a poem secretly professing his weight of chapter two released? Already have long since gone their roles as a unique brand of. In very clearly succeed at amc gift cards, it into derry should it will love letter years old mansion set our different from? Eddie accuse mike, who have your faaaaavorite love for new poster for one are having the coming up? He commits suicide, who has his wallet. -

IAN SEABROOK Underwater Director of Photography

IAN SEABROOK Underwater Director of Photography www.dorsalfin.net FEATURES DIRECTORS PRODUCERS/STUDIOS JUNGLE CRUISE Jaume Collet-Serra John Davis, John Fox, Danny Garcia, Hiram Garcia Disney IN THE SHADOW OF THE MOON Jim Mickle Rian Cahill, Brian Kavanaugh-Jones Linda Morgan, Ben Pugh / Netflix IT: CHAPTER 2 Andy Muschietti Seth Grahame-Smith, David Katzenberg, Roy Lee Dan Lin, Barbara Muscietti / Warner Bros. FONZO Josh Trank Russell Ackerman, Lawrence Bender Aaron L. Gilbert, John Schoenfelder / Universal ELI Ciaran Foy Trevor Macy, John Zaozirny / Paramount GLASS M. Night Shyamalan Mark Bienstock, Jason Blum, Ashwin Rajan Universal DEADPOOL 2 David Leitch Simon Kinberg, Lauren Shuler Donner / Fox PIRATES OF THE CARIBBEAN: Joachim Rønning Jerry Bruckheimer / Disney DEAD MEN TELL NO TALES & Esper Sandberg MONSTER TRUCKS Chris Wedge Mary Parent, Denis Stewart / Paramount ALPHA Albert Hughes Andrew Rona / Sony BATMAN VS. SUPERMAN: Zack Snyder Charles Roven. Deborah Snyder / Warner Bros DAWN OF JUSTICE UNDER THE SILVER LAKE. David Robert Mitchell Chris Bender, Michael De Luca, Jake Weiner / A24 TULLY Jason Reitman Diablo Cody, A.J. Dix, Helen Estabrook Aaron L. Gilbert, Beth Kono, Mason Novick Paramount POWER RANGERS Dean Isrealite Marty Bowen, Wyck Godfrey/ Lionsgate THE EDGE OF SEVENTEEN Kelly Fremon Craig Julie Ansell, James L. Brooks, Richard Sakai / STX THE SHACK Stuart Hazeldine Brad Cummings, Gil Netter / Lionsgate THE 9TH LIFE OF LOUIS DRAX Alex Aja Tim Bricknell, Max Minghella Shawn Williamson Miramax AGE OF ADALINE Lee Toland Krieger Gary Lucchesi, Tom Rosenberg / Lionsgate GODZILLA Gareth Edwards Jon Jashni, Mary Parent / Legendary HECTOR & THE SEARCH FOR Peter Chelsom Christian Angermayer, Klaus Dohle, Trish Dolman HAPPINESS Phil Hunt, Judy Tossell / Screen Siren MAN OF STEEL Zack Snyder Charles Roven, Deborah Snyder, Emma Thomas Warner Bros. -

Tracking the Research Trope in Supernatural Horror Film Franchises

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 2-2020 Legend Has It: Tracking the Research Trope in Supernatural Horror Film Franchises Deirdre M. Flood The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/3574 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] LEGEND HAS IT: TRACKING THE RESEARCH TROPE IN SUPERNATURAL HORROR FILM FRANCHISES by DEIRDRE FLOOD A master’s thesis submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Liberal Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts, The City University of New York 2020 © 2020 DEIRDRE FLOOD All Rights Reserved ii Legend Has It: Tracking the Research Trope in Supernatural Horror Film Franchises by Deirdre Flood This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Liberal Studies in satisfaction of the thesis requirement for the degree of Master of Arts. Date Leah Anderst Thesis Advisor Date Elizabeth Macaulay-Lewis Executive Officer THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii ABSTRACT Legend Has It: Tracking the Research Trope in Supernatural Horror Film Franchises by Deirdre Flood Advisor: Leah Anderst This study will analyze how information about monsters is conveyed in three horror franchises: Poltergeist (1982-2015), A Nightmare on Elm Street (1984-2010), and The Ring (2002- 2018). My analysis centers on the changing role of libraries and research, and how this affects the ways that monsters are portrayed differently across the time periods represented in these films. -

Melbourne It Announces Agreement with Yahoo! Melbourne IT Selected to Provide Domain Registration Services for Yahoo! Melbourne -- February

Melbourne It Announces Agreement With Yahoo! Melbourne IT Selected to Provide Domain Registration Services for Yahoo! Melbourne -- February. 13, 2001 -- Melbourne IT (ASX: MLB), a leading supplier of domain names and e-commerce infrastructure services to the global market, today announced an agreement with Yahoo! Inc. (Nasdaq:YHOO), a leading global Internet communications, commerce and media company. Through the agreement, Melbourne IT will provide .com, .net and .org domain names to users of Yahoo!® Domains (http://domains.yahoo.com), a service Yahoo! launched in May 2000 that allows people to search for, register and host their own domain names. "Yahoo! is synonymous with the Internet, and we believe the credibility associated with the Yahoo! brand will increase our domain name registrations and strengthen our position in the market," said Adrian Kloeden, Melbourne IT's Chief Executive Officer. "The agreement further supports Melbourne IT's strategy to become a leading worldwide provider of domain registration services and highlights our key strengths in providing domain names and related services." Also through the agreement, Melbourne IT will provide backend domain registrations for users of other Yahoo! properties, including Yahoo! Website Services (http://website.yahoo.com), Yahoo! Servers (http://servers.yahoo.com) and the Personal Address feature for Yahoo! Mail (http://mail.yahoo.com), all of which offer users a comprehensive suite of services to create and maintain a presence on the Web. "We are pleased to be working with Melbourne IT to provide Yahoo! Domains users with reliable and comprehensive domain name registration solutions," said Shannon Ledger, vice president and general manager, production, Yahoo!.