DRAFT Kwazulu-Natal Coastal Management Programme the Provincial Policy Directive for the Management of the Coastal Zone 2017 - 2022 First Published in 2017

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

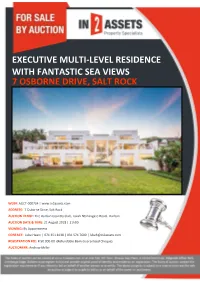

Executive Multi-Level Residence with Fantastic Sea Views 7 Osborne Drive, Salt Rock

EXECUTIVE MULTI-LEVEL RESIDENCE WITH FANTASTIC SEA VIEWS 7 OSBORNE DRIVE, SALT ROCK WEB#: AUCT-000734 | www.in2assets.com ADDRESS: 7 Osborne Drive, Salt Rock AUCTION VENUE: The Durban Country Club, Isaiah Ntshangase Road, Durban AUCTION DATE & TIME: 21 August 2018 | 11h00 VIEWING: By Appointment CONTACT: Luke Hearn | 071 351 8138 | 031 574 7600 | [email protected] REGISTRATION FEE: R 50 000-00 (Refundable Bank Guaranteed Cheque) AUCTIONEER: Andrew Miller CONTENTS 7 OSBORNE DRIVE, SALT ROCK 1318 Old North Coast Road, Avoca CPA LETTER 2 PROPERTY DESCRIPTION 3 PROPERTY LOCATION 4 PICTURE GALLERY 5 ADDITIONAL INFORMATION 11 TERMS AND CONDITIONS 13 SG DIAGRAM 14 TITLE DEED 15 ZONING CERTIFICATE 26 BUILDING PLANS 33 DISCLAIMER: Whilst all reasonable care has been taken to provide accurate information, neither In2assets Properties (Pty) Ltd nor the Seller/s guarantee the correctness of the information, provided herein and neither will be held liable for any direct or indirect damages or loss, of whatsoever nature, suffered by any person as a result of errors or omissions in the information provided, whether due to the negligence or otherwise of In2assets Properties (Pty) Ltd or the Sellers or any other person. The Consumer Protection Regulations as well as the Rules of Auction can be viewed at www.In2assets.com or at Unit 504, 5th Floor, Strauss Daly Place, 41 Richefond Circle, Ridgeside Office Park, Umhlanga Ridge. Bidders must register to bid and provide original proof of identity and residence on registration. Version 4: 20.08.2018 1 CPA LETTER 7 OSBORNE DRIVE, SALT ROCK 1318 Old North Coast Road, Avoca In2Assets would like to offer you, our valued client, the opportunity to pre-register as a bidder prior to the auction day. -

Ethembeni Cultural Heritage

FINAL REPORT PHASE 1 HERITAGE IMPACT ASSESSMENT REPORT: SCOPING AND ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT FOR THE PROPOSED EXPANSION OF PIETERMARITZBURG AIRPORT, MSUNDUZI MUNICIPALITY, KWAZULU-NATAL Prepared for Institute of Natural Resources 67 St Patricks Road, Pietermaritzburg, 3201 Box 100396, Scottsville, 3209 Telephone David Cox 033 3460 796; 082 333 8341 Fax 033 3460 895 [email protected] Prepared by eThembeni Cultural Heritage Len van Schalkwyk Box 20057 Ashburton 3213 Pietermaritzburg Telephone 033 326 1815 / 082 655 9077 Facsimile 086 672 8557 [email protected] 03 January 2017 PHASE 1 HERITAGE IMPACT ASSESSMENT OF EXPANSION OF PIETERMARITZBURG AIRPORT, KWAZULU-NATAL MANAGEMENT SUMMARY eThembeni Cultural Heritage was appointed by the Institute of Natural Resources to undertake a Phase 1 Heritage Impact Assessment of the proposed expansion of Pietermaritzburg Airport, as required by the National Environmental Management Act 107 of 1998 as amended (NEMA), in compliance with Section 38 of the National Heritage Resources Act 25 of 1999 (NHRA). Description and significance assessment of heritage resources Pietermaritzburg Aeroclub Clubhouse The building is older than sixty years and located next to the modern airport terminal buildings. Its continued use for the same purpose over a period of more than sixty years, including its expansions, contribute to give it medium to high heritage significance at community-specific and local levels for its historic, social and cultural values. Its associational value could extend further if it proves that the nearby Italian POW church and the clubhouse were both constructed from Hlatshana shale, and that the construction of the former gave rise to the use of a locally novel material to build the latter. -

Kim Spingorum

Kindly be advised should you be coming with a boat, jet skis or canoe/kayak to contact our local ski boat club manager, contact person Charles Rautenbach, to get the necessary clearances or any additional info re water sport facilities on the lagoon. Cell: 083 375 5399 Brian is the local skipper for all things fishing and for booking a cruise on the barge on the lagoon – for more details contact, 084 446 6813 / 074 479 0987. Have fun! (Ocean echo fishing charters) Or simply just paddle, fish or swim in our lagoon. – Double or single canoes for hire at R40/per hour from the Lagoon lodge – contact: 032 – 485 3344 For additional water escapades in Durban and surrounds including Ballito please have a look at https://adventureescapades.co.za/water-adventures-in-south-africa/ Sugar Rush fun park for the whole family – www.sugarrush.co.za - on the coastal farmland of the North Coast, on the outskirts of Ballito – please have a look at the website for more information. • Putt-putt with paddling pools after the kids have played their holes • Small winery • The Jump Park • Tuwa Beauty Spa • Petting Zoo – Feathers and Furballs • Sugar rats – Kids Mountain biking, safe and fun! • Reptile Park • Restaurant Holla Trails operates from Sugar rush For those who are interested in doing a bike or for the runners!!– Holla trails can be contacted on +27 074 897 8559 (trail master) or 082 899 3114 (desk phone) – Easy to get to situated on the outskirts of Ballito! A fun way to experience the farm life on the North Coast, the trails are for different levels from under 12 to 70 years. -

Cultural and Heritage Impact Assessment

APPENDIX M Cultural and Heritage Impact Assessment eThembeni Cultural Heritage Heritage Impact Assessment Report Proposed Lanele Terminal 1. (Lot 1) Project, Ambrose Park, Bayhead Durban Harbour eThekweni Municipality Report prepared for: Report prepared by: Golder Associates Africa (Pty) Ltd. eThembeni Cultural Heritage Building 1, Golder House, Maxwell Office Park, P O Box 20057 Magwa Crescent West, Waterfall City ASHBURTON P.O. Box 6001, Halfway House, 1685 3213 Midrand, South Africa, 1685 Tel: +27 11 254 4800 | Fax: +27 86 582 1561 16 January 2019 DECLARATION OF INDEPENDENCE I, Leonard van Schalkwyk, declare that – I act as the independent specialist in this application. I will perform the work relating to the application in an objective manner even if this results in views and findings that are not favourable to the applicant. I declare that there are no circumstances that may compromise my objectivity in performing such work. I have no, and will not engage in, conflicting interests in the undertaking of the activity. I undertake to disclose to the applicant and the competent authority all material information in my possession that reasonably has or may have the potential of influencing any decision to be taken with respect to the application by the competent authority; and the objectivity of any report, plan or document to be prepared by myself for submission to the competent authority. All the particulars furnished by me in this form are true and correct. Signed 16 January 2019 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY INTRODUCTION eThembeni Cultural Heritage was appointed by Golder Associates Africa (Pty) Ltd, to conduct a Phase1 Heritage Impact Assessment (HIA) for the establishment of a new liquid fuel storage and handling facility, the Lanele Oil Terminal 1 (Lot 1) project, on a portion of the Kings Royal Flats No. -

Chapter 4 Kwadukuza Environmental Management

1 INTEGRATED DEVELOPMENT PLAN 2011 / 16 KwaDukuza Municipality CHAPTER 1: Executive Summary 1.1 KwaDukuza Powers and Functions 6 1.2 KwaDukuza long-term vision 6 1.3. KwaDukuza Mission 7 1.4. KwaDukuza Development Strategies 7 1.5. ILembe at Glance 7 1.6. KwaDukuza Broad Geographical Context 8 1.7. Opportunities Offered by KwaDukuza Municipality 10 1.8. KwaDukuza Strength, Weaknesses, 11 Opportunities and Threats Analysis 1.9. Institutional Arrangement 12 CHAPTER 2: KwaDukuza Situational Analysis 2.1. Population Statistics 16 2.2. Age of the population 16 2.3. Education and Skills 16 2.4. Employment Profile 16 2.5. Income Levels 16 2.6. HIV & AIDS Prevalence 16 2.7. Environmental Context 16 2.8. Biophysical Context 16 2.9. Infrastructural Context 17 2.10. Transportation 17 2.11. Priority Needs 17 2.12. Current Use of Land 17 CHAPTER 3: Good Governance & Community Participation 3.1. Introduction 20 3.2. Ward Committees 20 3.3. Community Based Planning 20 3.4. Role of local community and ward councillors in integrated 21 development planning process 3.5 Co-Operative Governance 22 CONTENTS CHAPTER 4: KwaDukuza Environmental Management 4.1 KwaDukuza Municipality Environmental Management 26 4.2. White paper on National Environmental 26 Management Act, 1998 4.3. Linkages with principles of National 26 Environmental Management Act, (107 of 1998) 4.4. Environmental Management Tools: 28 4.5. Urban Development Framework 28 4.6. Involvement of Environmental NGO/NPOs 28 Sustainability framework - KwaDukuza Strategic 30 Environmental Assessment 4.7. Waste Management Hierarchy 30 4.8. Strategies and Priorities for Integrated Waste Management 31 4.9. -

C:\Users\Molatlhwe.Molefe\Appdata

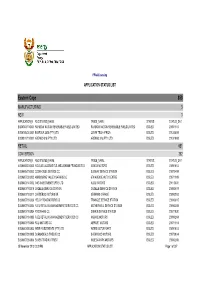

PPAA Licensing APPLICATION STATUS LIST Eastern Cape 853 MANUFACTURING 3 NEW 3 APPLICATION_N REGISTERED_NAME: TRADE_NAME: STATUS: STATUS_DAT B/2007/04/10/0001 RAINBOW NATION RENEWABLE FUELS LIMITED RAINBOW NATION RENEWABLE FUELS LIMITED ISSUED 2008/11/13 B/2007/06/04/0001 BASFOUR 3528 (PTY) LTD CLEAN TECH AFRICA ISSUED 2013/05/09 B/2008/10/10/0001 ARENGO 316 (PTY) LTD ARENGO 316 (PTY) LTD ISSUED 2013/10/08 RETAIL 451 CONVERSION 382 APPLICATION_N REGISTERED_NAME: TRADE_NAME: STATUS: STATUS_DAT A/2006/08/30/0002 NICOLAS JACOBUS ELS AND JOHANN FRANCOIS ELS KOMGA MOTORS ISSUED 2009/10/13 B/2006/06/30/0002 COOKHOUSE SERVICE CC SUBWAY SERVICE STATION ISSUED 2007/04/04 B/2006/07/03/0002 ASHBOURNE VALLEY SAFARIS CC 6TH AVENUE AUTO CENTRE ISSUED 2007/11/09 B/2006/07/14/0002 INXS INVESTMENTS (PTY) LTD KUDU MOTORS ISSUED 2011/03/31 B/2006/07/18/0010 GAZELLE SERVICE STATION GAZELLE SERVICE STATION ISSUED 2008/05/19 B/2006/07/18/0011 CAMDEBOO MOTORS BK SEAMANS GARAGE ISSUED 2009/02/03 B/2006/07/18/0023 HEUGH ROAD MOTORS CC TRIANGLE SERVICE STATION ISSUED 2009/03/15 B/2006/07/18/0024 FUEL RETAILING MANAGEMENT SERVICES CC MOTHERWELL SERVICE STATION ISSUED 2009/02/04 B/2006/07/18/0034 RYDONHAM CC DONKIN SERVICE STATION ISSUED 2007/10/30 B/2006/07/18/0035 FUEL RETAILING MANAGEMENT SERVICES CC KABANE MOTORS ISSUED 2009/02/04 B/2006/07/18/0036 ROLI MOTORS CC AIRPORT MOTORS ISSUED 2007/11/14 B/2006/07/28/0003 WEIR INVESTMENTS (PTY) LTD WEIRS MOTOR MART ISSUED 2009/10/13 B/2006/07/28/0005 DORMADEALS TWELVE CC SHERWOOD MOTORS ISSUED 2007/09/14 B/2006/07/28/0006 -

KZN Administrative Boundaries Western Cape 29°0'0"E 30°0'0"E 31°0'0"E 32°0'0"E 33°0'0"E

cogta Department: Locality Map Cooperative Governance & Traditional Affairs Limpopo Mpumalanga North West Gauteng PROVINCE OF KWAZULU-NATAL Free State KwaZulu-Natal Northern Cape Eastern Cape KZN Administrative Boundaries Western Cape 29°0'0"E 30°0'0"E 31°0'0"E 32°0'0"E 33°0'0"E Mozambique Mboyi Swaziland 5! Kuhlehleni 5! Kosi Bay 5! Manyiseni MATENJWA 5! Ndumo MPUMALANGA T. C 5! KwaNgwanase Jozini Local 5! 5! Manguzi 27°0'0"S Nkunowini Boteler Point 27°0'0"S 5! Municipality 5! (KZN272) Sihangwane 5! Phelandaba 5! MNGOMEZULU T. C TEMBE Kwazamazam T. C 5! Dog Point Machobeni 5! 5! Ingwavuma 5! Mboza Umhlabuyalingana Local ! 5 Municipality (KZN271) NYAWO T. C Island Rock 5! Mpontshani 5! Hully Point Vusumuzi 5! 5! Braunschweig 5! Nhlazana Ngcaka Golela Ophondweni ! 5! Khiphunyawo Rosendale Zitende 5! 5! 5 5! 5! 5! KwaNduna Oranjedal 5! Tholulwazi 5! Mseleni MASHBANE Sibayi 5! NTSHANGASE Ncotshane 5! 5! T. C 5! T. C NTSHANGASE T. C SIQAKATA T. C Frischgewaagd 5! Athlone MASIDLA 5! DHLAMINI MSIBI Dumbe T. C SIMELANE 5! Pongola Charlestown 5! T. C T. C Kingholm 5! T. C Mvutshini 5! Othombothini 5! KwaDlangobe 5! 5! Gobey's Point Paulpietersburg Jozini 5! Simlangetsha Fundukzama 5! 5! ! 5! Tshongwe 5 ! MABASO Groenvlei Hartland 5 T. C Lang's Nek 5! eDumbe Local 5! NSINDE 5! ZIKHALI Municipality Opuzane Candover T. C 5! Majuba 5! 5! Mbazwana T. C Waterloo 5! (KZN261) MTETWA 5! T. C Itala Reserve Majozini 5! KwaNdongeni 5! 5! Rodekop Pivana 5! ! Emadlangeni Local ! 5! Magudu 5 5 Natal Spa Nkonkoni Jesser Point Boeshoek 5! 5!5! Municipality 5! Ubombo Sodwana Bay Louwsburg UPhongolo Local ! (KZN253) 5! 5 Municipality Umkhanyakude (KZN262) Mkhuze Khombe Swaartkop 5! 5! 5! District Madwaleni 5! Newcastle 5! Utrecht Coronation Local Municipality 5! 5! Municipality NGWENYA Liefeldt's (KZN252) Entendeka T. -

Ilembe District Municipality – Quarterly Economic Indicators and Intelligence Report: 4Th Quarter 2011

iLembe District Municipality – Quarterly Economic Indicators and Intelligence Report: 4th Quarter 2011 ILEMBE DISTRICT MUNICIPALITY NOVEMBER 2010 QUARTERLY ECONOMIC INDICATORSNOVEMBER 2010 AND INTELLIGENCE REPORT FOURTH QUARTER October - December 2011 Enterprise iLembe Cnr Link Road and Ballito Drive Ballito, KwaZulu-Natal Tel: 032 – 946 1256 Fax: 032 – 946 3515 iLembe District Municipality – Quarterly Economic Indicators and Intelligence Report: 4th Quarter 2011 FOREWORD This intelligence report comprises of an assessment of key economic indicators for the iLembe District Municipality for the fourth quarter of 2011, i.e. October to December 2011. This is the fourth edition of the quarterly reports which are unique to iLembe as we are the only district municipality to publish such a report. The overall objective of this project is to present economic indicators and economic intelligence to assist Enterprise iLembe in driving its mandate, which is to promote trade and investment and to drive economic development in the District of iLembe. This quarter’s edition not only describes historical trends but also takes a brief look at the future of iLembe through the eyes of district planners. Their plan looks forward 30 years to an iLembe that is thriving of the back of large scale agricultural, manufacturing, resort, and renewable energy investments. The result is a highly connected and integrated district, where Ballito and KwaDukuza have formed a metro, and the north coast has become the tourism destination of choice. Readers are asked to comment on this future scenario and the steps needed to get there. This quarter’s report provides also an update on the work we, at Enterprise iLembe, are doing. -

![Reinforcement of Salt Rock Sea Wall Draft Basic Assessment Report [Dc29/0023/2017]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4452/reinforcement-of-salt-rock-sea-wall-draft-basic-assessment-report-dc29-0023-2017-3104452.webp)

Reinforcement of Salt Rock Sea Wall Draft Basic Assessment Report [Dc29/0023/2017]

SALT ROCK BEACH ESTATES CC REINFORCEMENT OF SALT ROCK SEA WALL DRAFT BASIC ASSESSMENT REPORT [DC29/0023/2017] FEBRUARY 15, 2018 PUBLIC REINFORCEMENT OF SALT ROCK SEA WALL DRAFT BASIC ASSESSMENT REPORT [DC29/0023/2017] SALT ROCK BEACH ESTATES CC TYPE OF DOCUMENT (VERSION) PUBLIC PROJECT NO.: 48410 DATE: FEBRUARY 2018 WSP BLOCK A, 1 ON LANGFORD LANGFORD ROAD, WESTVILLE DURBAN, 3629 SOUTH AFRICA T: +27 31 240 8803 F: +27 31 240 8801 WSP.COM WSP Environmental (Pty) Ltd. QUALITY MANAGEMENT ISSUE/REVISION FIRST ISSUE REVISION 1 REVISION 2 REVISION 3 Draft Remarks 15 February 2018 Date D Sanderson Prepared by Signature C Elliott Checked by Signature N Seed Authorised by Signature 48410 Project number 1 Report number File reference G:\000 NEW Projects\48410 - Salt Rock Hotel BA & EMPr\42 ES\2-REPORTS\01- Draft SIGNATURES PREPARED BY Carla Elliott, Principal Consultant - Environmental Services REVIEWED BY Nigel Seed, Director - Environmental Services This report was prepared by WSP Environmental (Pty) Ltd. for the account of SALT ROCK BEACH ESTATES CC, in accordance with the professional services agreement. The disclosure of any information contained in this report is the sole responsibility of the intended recipient. The material in it reflects WSP Environmental (Pty) Ltd’s best judgement in light of the information available to it at the time of preparation. Any use which a third party makes of this report, or any reliance on or decisions to be made based on it, are the responsibility of such third parties. WSP Environmental (Pty) Ltd. accepts no responsibility for damages, if any, suffered by any third party as a result of decisions made or actions based on this report. -

KZN Liquor Licences 2013

LIQUOR LICENCES 2013 MR MIKE MABUYAKHULU MRS STELLA KHUMALO MEC: Department of Economic CEO: KwaZulu-Natal Development and Tourism Liquor Authority NOTICE TO ALL LIQUOR LICENCE HOLDERS KZN Liquor Authority striving to be the leading liquor regulator in the country 2 LIQUOR LICENCES 2013 HIS notice serves to inform all current licence holders that the KwaZulu-Natal Liquor Authority has finalized the list of all licences for which renewal fees have been paid and received from licence holders for the trading year 2013 and licenses which were granted from July to March 2013 . As part of the ongoing data validation process, we attach a list of all renewed licenses for the period TOctober 1 2012 to February 28 2013. All licenses renewed after February 28 2013 are deemed invalid and lapsed as they fall outside the renewal period as prescribed by the Liquor Act, 1989 ( 27 of 1989).Those affected must cease trading and re-apply for new liquor licenses. If you have renewed your licence and your license details do not appear in the list below please contact Ms Nondumiso Ngcobo on 031 302 0600, with a copy of your ABSA deposit slip as proof of payment together with an affidavit reflecting your contact details, to update our records. Deposit slips can be forwarded to us by fax: 086 628 7011 or e-mail: [email protected] or alternatively hand deliver to our reception at The Marine Buliding, 1st Floor, 22 Dorothy Nyembe Street, Durban. Premises Name License Holder Name License number License Type Premises Name License Holder Name License number License Type 54 Pegma 104 Investments CC KZN/020429 (Special Liquor Licence (Other) Aliwal Dive Centre Aliwal Dive Charters CC KZN/030861 (Special Liquor Licence (Other) @Ed`S Ristorante Men Restaurant CC KZN/032595 Restaurant Liquor Licence Aljaren Pub And Diner Aljaren Pub And Diner C.C. -

Í Cross Boundary Linkages

$R CROSS BOUNDARY.! LINKAGES - SDF 2020-2021 Mpolweni Wartburg Montebello .! D 2 7 ! 21 0 . 8 D KwaDukuza Shakas Kraal .! D 2 2 Tinley Manor D73 0 5 Local Kleine Municipality D 4 Waterval 5 Umhlali D16 7 2 2 6 3 2 O D D 1 .! 0 .! 1 3 D1 Windy Hill Swayimane 02 2 5 1 0 1 D R $ Compensation D Salt Rock 1 0 ! D . D uMshwathi 1 1 0 6 9 6 1 1 8 Ndwedwe iLembe Black Rock 86 D1 Local D1017 D1023 D D2052 .! 5 .! 9 Municipality 9 Ballito Shaka's Rock u T &: h Lower Tugela o Compensation Beach n .! .!R614 g .! Wewe UMgungundlovu a t 8 D Ndwedwe h 40 21 D 66 i R Ezindlovini ive r .! Swayimana Local .! Salmon Bay 90 6 D 5 2 6 D 0 .! 5 1 D 9 Municipality D319 Tongaat 45 D2 Finney's Rock H Hazelmere l aw # i S e R v r Embeka Dam e M43 Table Mountain M36 D D 10 u 10 06 r 01 M ive Westbrook Beach D ti R n¡ 1 0 d l o 0 D D5 0 75 15 Nonzila 2 0 8 8 8 D !r 9 2170 6 D 6 D Makhlanjalo/Abebhuzi o Pietermaritzburg 8 6 2 3 M M 10 2 zi 38 R D n y 5 a 8 5 t D Nkanyeni i S Dube t m D Manyavu r ea $ 3 r Verulam 1 e 8 9 B la la i v Trade 3 c M h i R 7 k s in 1 .! 2 2 7 D 1 2 Port D Inanda S# M27 M4 M54 M 58 Dam D1021 1 KwaXimba 2 0 1 S# Ashburton D 6 Umdloti Beach 0 Umzinyathi 5 D S! Umdloti M26 M e r !r 2 S# iv 5 s 3 h n¡ M28 57 hlang R D M O a w M 52 a M2 O 3 5 t 2 t i S M t t n¡ a S r w 6 D80 ea a i 4 m 6 M D 5 4 5 k M 1 1 3 S 9 S D e 0 l e Bridh ge tr k e D Inchanga a e m 4 e 5 1 h Umhlanga 8 m M 7 7 4 6 l r Cato Ridge M45 b ve Umhlanga Rocks D e i e City R ni e # S iv r S e R tr m D 103 a Inanda R 1 iesa !r 2 S# Camperdown b R P g 5 S# b o Uitsoek ho h o # n -

Ilembe UAP Phase 2 Final Report

Umgeni Water UNIVERSAL ACCESS PLAN FOR WATER SERVICES PHASE 2: PROGRESSIVE DEVELOPMENT OF A REGIONAL CONCEPT PLAN FOR BULK WATER SERVICES REPORT ILEMBE DISTRICT MUNICIPALITY CONTRACT NO. 2015/178 June 2016 STATUS: FINAL Prepared for: Compiled by: Umgeni Water Hatch Goba 310 Burger Street, PMB 25 Richefond Circle, Ridgeside Office Park, PO Box 9, PMB, 3200 Umhlanga, Durban, South Africa, 4321 Tel: (033) 341 1111 Tel: +27(0) 31 536 9400 Fax: (033) 341 1084 Fax: +27(0) 31 536 9500 Attention: Mr Vernon Perumal e-mail: [email protected] Enquiries: Mr G. Morgan In Association with JTN Consulting (Pty) Ltd H350226-00000-100-066-0010, Rev 3 Universal Access Plan Phase 2 Final Report – Ilembe District Municipality June 2016 REPORT CONTROL PAGE Report control Client: Umgeni Water Project Name: Universal Access Plan (For Water Services) Phase 2: Progressive Development Of A Regional Concept Plan Project Stage: Phase 2: Project Report Report title: Project Report Report status: Final Project reference no: 2663-00-00 Report date: June 2016 Quality control Written by: Shivesh Dinanath- JTN Consulting Reviewed by: Busiswa Maome – JTN Consulting Approved by: Pragin Maharaj Pr Tech Eng – JTN Consulting Date: 20 June 2016 Document control Version History: Version Date changed Changed by Comments 0 31 March 2016 PM Issued for Use 1 16 May 2016 PM Second Draft for Comment 2 20 June 2016 PM Final 3 24 June 2016 PM Final H350226-00000-100-066-0010, Rev 3 i Universal Access Plan Phase 2 Final Report – Ilembe District Municipality June 2016 Contents REPORT CONTROL ............................................................................................................................................... I QUALITY CONTROL .............................................................................................................................................