Arxiv:2102.01755V2 [Hep-Ph] 4 Mar 2021 Rect Solution with the Discovery of the Matter-Induced of Ssms with Different Metallicities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Recommended Conventions for Reporting Results from Direct Dark Matter Searches

Recommended conventions for reporting results from direct dark matter searches D. Baxter1, I. M. Bloch2, E. Bodnia3, X. Chen4,5, J. Conrad6, P. Di Gangi7, J.E.Y. Dobson8, D. Durnford9, S. J. Haselschwardt10, A. Kaboth11,12, R. F. Lang13, Q. Lin14, W. H. Lippincott3, J. Liu4,5,15, A. Manalaysay10, C. McCabe16, K. D. Mor˚a17, D. Naim18, R. Neilson19, I. Olcina10,20, M.-C. Piro9, M. Selvi7, B. von Krosigk21, S. Westerdale22, Y. Yang4, and N. Zhou4 1Kavli Institute for Cosmological Physics and Enrico Fermi Institute, University of Chicago, Chicago, IL 60637 USA 2School of Physics and Astronomy, Tel-Aviv University, Tel-Aviv 69978, Israel 3University of California, Santa Barbara, Department of Physics, Santa Barbara, CA 93106, USA 4INPAC and School of Physics and Astronomy, Shanghai Jiao Tong University, MOE Key Lab for Particle Physics, Astrophysics and Cosmology, Shanghai Key Laboratory for Particle Physics and Cosmology, Shanghai 200240, China 5Shanghai Jiao Tong University Sichuan Research Institute, Chengdu 610213, China 6Oskar Klein Centre, Department of Physics, Stockholm University, AlbaNova, Stockholm SE-10691, Sweden 7Department of Physics and Astronomy, University of Bologna and INFN-Bologna, 40126 Bologna, Italy 8University College London, Department of Physics and Astronomy, London WC1E 6BT, UK 9Department of Physics, University of Alberta, Edmonton, Alberta, T6G 2R3, Canada 10Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (LBNL), Berkeley, CA 94720, USA 11STFC Rutherford Appleton Laboratory (RAL), Didcot, OX11 0QX, UK 12Royal Holloway, -

The INT @ 20 the Future of Nuclear Physics and Its Intersections July 1 – 2, 2010

The INT @ 20 The Future of Nuclear Physics and its Intersections July 1 – 2, 2010 Program Thursday, July 1: 8:00 – 8:45: Registration (Kane Hall, Rom 210) 8:45 – 9:00: Opening remarks Mary Lidstrom, Vice Provost for Research, University of Washington David Kaplan, INT Director Session chair: David Kaplan 9:00 – 9:45: Science & Society 9:00 – 9:45 Steven Koonin, Undersecretary for Science, DOE The future of DOE and its intersections 9:45 – 10:30: Strong Interactions and Fundamental Symmetries 9:45 – 10:30 Howard Georgi, Harvard University QCD – From flavor SU(3) to effective field theory 10:30 – 11:00: Coffee Break Session chair: Martin Savage 11:00 – 11:30 Silas Beane, University of New Hampsire Lattice QCD for nuclear physics 11:30 – 12:00 Paulo Bedaque, University of Maryland Effective field theories in nuclear physics 12:00 – 12:30 Michael Ramsey-Musolf, University of Wisconsin Fundamental symmetries of nuclear physics: A window on the early Universe 12:30 – 2:00: Lunch (Mary Gates Hall) 1 Thursday, July 1 2:00 – 5:00: From Partons to Extreme Matter Session chair: Gerald Miller 2:00 – 2:30 Matthias Burkardt, New Mexico State University Transverse (spin) structure of hadrons 2:30 – 3:00 Barbara Jacak, SUNY Stony Brook Quark-gluon plasma: from particles to fields? 3:00 – 3:45 Raju Venugopalan, Brookhaven National Lab Wee gluons and their role in creating the hottest matter on Earth 3:45 – 4:15: Coffee Break Session chair: Krishna Rajagopal 4:15 – 4:45 Jean-Paul Blaizot, Saclay Is the quark-gluon plasma strongly or weakly coupled? 4:45 -

Tritium Beta Decay and the Search for Neutrino Mass

ritium Beta Decay and the Search for Neutrino Mass Tritium Beta Decay and the Search for Neutrino Mass eutrinos have been around, that the decay also produced a second neutrino mass. A short lifetime literally, since the beginning unseen particle, now called the means atoms decay more rapidly, Nof time. In the sweltering electron neutrino. The neutrino would making more data available. moments following the Big Bang, share the energy released in the decay A wonderful accident of nature, tri- neutrinos were among the first particles with the daughter atom and the tium (a hydrogen atom with two extra Tritium Beta Decay and the Search to emerge from the primordial sea. electron. The electrons would emerge neutrons) is a perfect source by both A minute later, the universe had cooled with a spectrum of energies. of these measures: it has a reasonably for Neutrino Mass enough for protons and neutrons In 1934, Enrico Fermi pointed out short lifetime (12.4 years) and releases to bind together and form atomic that, if the neutrino had mass, it would only 18.6 kilo-electron-volts (keV) Thomas J. Bowles and R. G. Hamish Robertson as told to David Kestenbaum nuclei. Ten or twenty billion years subtly distort the tail of this spectrum. as it decays into helium-3. later—today—the universe still teems When an atom undergoes beta decay, it Additionally, its molecular structure with these ancient neutrinos, which produces a specific amount of available is simple enough that the energy outnumber protons and neutrons by energy that is carried away by the spectrum of the decay electrons can roughly a billion to one. -

Neutrino Mass and Oscillations 1 Introduction

Neutrino Mass and Oscillations R. G. Hamish Robertson Department of Physics, University of Washington Seattle, WA 98195 1 Introduction The neutrino remains as exotic and challenging today as it was seventy years ago when first proposed by Pauli. What is known for certain about neutrinos is minimal indeed. They have spin 1 , charge 0, negative helicity, and exist in 3 2 flavors, electron, mu, and tau. Strictly speaking, only 2 flavors are certain: direct observation of the tau neutrino has not yet been achieved, but an experiment, DONUT, at Fermilab is in progress with this objective [1]. Limits on the masses from direct, kinematic experiments (ones that do not require assumptions about the non-conservation of lepton family numbers) have been steadily lowered by experiments of ever-increasing sophistication over the years, with the results given in Table 1. As will be discussed below, there are stronger limits on the mass of νe from tritium beta decay [2, 3], but the data show curious distortions near the endpoint that are not at present understood. Electron Family νe < 15 eV e− 510999.06 eV Mu Family νµ < 170keV µ− 105658.389 keV Tau Family ντ < 18 MeV τ− 1777.1 MeV Table 1: The kinematic mass limits for neutrinos, compared to the known masses of their charged-lepton partners [4] There are strong theoretical and experimental motivations to search for neu- trino mass. Presumably created in the early universe in numbers comparable to photons, neutrinos with a mass of only a few eV would contribute a significant 2 fraction of the closure density. -

Newsletter No. 94

DNP Newsletter No. 94 MAY 1993 TO: Members of the Division of Nuclear Physics, APS FROM: Virginia R. Brown, LLNL - Secretary-Treasurer, DNP • 9 July 1993- Election Ballot for ACCOMPANYING THIS NEWSLETTER DNP Div. Councilor (See item 2). : • 9 July 1993- Nomination Ballot for • A ballot for the nomination of DNP DNP Elections (See item 3). Officers and Executive Committee. • 9 July 1993- Ballot for DNP New Bylaws (See item 4). • A ballot for voting for a second • 1 Sept. 1993-Nominations for 1994 DNP Division Councilor. Dissertation Award (See item 5). • A ballot for the Adoption of the • 1 Sept. 1993-Nominations for 1994 New DNP Bylaws. Bonner Prize (See item 6). • "New" DNP Bylaws. • 17 Sept. 1993-Last day for Asilomar "Special" Preregistration rates and last day for lodging 20-23 OCTOBER DNP MEETING, reservations at the Asilomar ASILOMAR, CA conference grounds. • A pre-registration form which includes workshops and banquet. • A housing form. 1. DNP COMMITTEES Future Deadlines Executive Committee Noemie Benczer-Koller, Rutgers 1993-94 Univ., Chair (1994) DNP Carl B. Dover, BNL, Vice-Chair (1994) Wick C. Haxton, Univ. of • 18 June 1993- Contributed Washington, Past-Chair (1994) Abstracts for the Asilomar Fall Meeting (See item 9). • 25 June 1993 - User Group Virginia R. Brown, LLNL, Secretary- Deadline in Order to Appear in Treasurer (1994) the October Bulletin (See item 9). Gerald T. Garvey, LANL, Division Councilor (December, 1993) Stephen E. Koonin, Caltech, Division S. Kowalski, MIT Councilor (December, 1995) R. E. Pollock, Indiana Univ. Lawrence S. Cardman, CEBAF (1994) 1995 Bonner Prize Committee Walter Henning, ANL (1994) Robert D. -

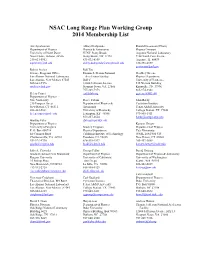

NSAC Subcommittee Membership List

NSAC Long Range Plan Working Group 2014 Membership List Ani Aprahamian Abhay Deshpande Donald Geesaman (Chair) Department of Physics Physics & Astronomy Physics Division University of Notre Dame SUNY Stony Brook Argonne National Laboratory Notre Dame, Indiana 46556 Stony Brook, NY 11794 9700 South Cass Avenue 219-631-5952 631-632-8109 Argonne, IL 60439 [email protected] [email protected] 630-252-4059 [email protected] Robert Atcher Rolf Ent Science Programs Office, Thomas Jefferson National Geoffrey Greene Los Alamos National Laboratory Accelerator Facility Physics Department Los Alamos, New Mexico 87545 Hall C University of Tennessee 505-663-5596 12000 Jefferson Avenue 515 Nielson Building [email protected] Newport News, VA 23606 Knoxville, TN 37996 757-269-7373 865-974-3342 Helen Caines [email protected] [email protected] Department of Physics Yale University Renee Fatemi John Hardy 215 Prospect Street Department of Physics & Cyclotron Institute New Haven, CT 06511 Astronomy Texas A&M University 203-432-5831 University of Kentucky College Station, TX 77843 [email protected] Lexington, KY 40506 979-845-1411 859-257-2664 [email protected] Gordon Cates [email protected] Department of Physics Karsten Heeger University of Virginia Bradley Filippone Department of Physics P. O. Box 400714 Physics Department Yale University McCormick Road California Institute of Technology WNSL 206/JWG 515 Charlottesville, VA 22903 Pasadena, CA 92225 New Haven, CT 06520 434-924-4790 626-395-4517 203-432-3088 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] -

Stuart J. Freedman

Stuart Jay Freedman 1944–2012 A Biographical Memoir by R. G. Hamish Robertson ©2014 National Academy of Sciences. Any opinions expressed in this memoir are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Academy of Sciences. STUART JAY FREEDMAN January 13, 1944–November 10, 2012 Elected to the NAS, 2001 Stuart J. Freedman was an experimental physicist with a broad sweep of talents and interests that centered on nuclear physics but also spanned particle physics, quantum mechanics, astrophysics, and cosmology. As a graduate student at the University of California, Berkeley, he carried out a crucial test of the Einstein-Podolsky- Rosen (EPR) argument that quantum mechanics was an incomplete theory; Stuart showed that EPR’s postulated local hidden variables did not explain experimental data, whereas quantum mechanics did. Stuart was an early and continuous leader in the search for neutrino oscilla- tions, and in the KamLAND project he determined which of several possible solutions the correct one was. He also was noted for several instances in which an incorrect By R. G. Hamish Robertson result with major implications was neutralized. Perhaps the most famous case involved the 17-keV neutrino. Stuart was born in Hollywood, CA—the son of David Freedman, an architect, and Anne (Sklar) Freedman—and attended schools in Beverlywood. By all accounts he was a strong student and a “normal” teenager, with a penchant for ruffling establishment feathers whenever possible. His occasional minor run-ins with the law and hilarious interactions with bureaucracies became the stuff of good stories later in life. -

Direct Probes of Neutrino Mass

Nuclear Physics B Proceed- ings Nuclear Physics B Proceedings Supplement 00 (2018) 1–6 Supple- ment Direct probes of neutrino mass R. G. Hamish Robertson Center for Experimental Nuclear Physics and Astrophysics and Dept. of Physics, University of Washington, Seattle WA 98195, USA Abstract The discovery of neutrino oscillations has shown that neutrinos, in contradiction to a prediction of the minimal standard model, have mass. Oscillations do not yield a value for the mass, but do set a lower limit of 0.02 eV on the average of the 3 known eigenmasses. Moreover, they make it possible to determine or limit all 3 masses from measurements of electron-flavor neutrinos in beta decay. The present upper limit from such measurements is 2 eV. We review the status of laboratory work toward closing the remaining window between 2 and 0.02 eV, and measuring the mass. Keywords: Neutrino mass, beta decay, tritium, electron spectroscopy 1. Introduction conservation in the weak interaction in 1956 [6] and the measurement of the helicity of the neutrino in 1958 [7] The mass of the neutrino has been a topic of specula- made plausible the idea that the neutrino was massless, tion and research since the theory of beta decay was for- and massless neutrinos were subsequently built into the mulated by Fermi [1]. Neutrino mass affects the shape standard model. A decade-long hiatus in searches for of the beta spectrum, and even with the limited data neutrino mass followed. A second kind of neutrino, available at the time, Fermi was able to conclude that the muon neutrino, was discovered in 1962 [8], and the mass of the neutrino must be “either zero, or in any a third, the tau neutrino, was found to exist in 1975 case very small, in comparison to the mass of the elec- [9]. -

![Arxiv:1208.5723V1 [Astro-Ph.SR] 28 Aug 2012 Key Words Solar Neutrinos, Neutrino Oscillations, Solar Models, Helioseismol](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9335/arxiv-1208-5723v1-astro-ph-sr-28-aug-2012-key-words-solar-neutrinos-neutrino-oscillations-solar-models-helioseismol-6069335.webp)

Arxiv:1208.5723V1 [Astro-Ph.SR] 28 Aug 2012 Key Words Solar Neutrinos, Neutrino Oscillations, Solar Models, Helioseismol

1 Solar Neutrinos: Status and Prospects W. C. Haxton Department of Physics, University of California, Berkeley, and Nuclear Science Division, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, Berkeley CA 94720-7300 R. G. Hamish Robertson Department of Physics, University of Washington, and Center for Experimental Nuclear Physics and Astrophysics, Seattle, WA 98195 Aldo M. Serenelli Instituto de Ciencias del Espacio (CSIC-IEEC), Facultad de Ciencias, Campus UAB, 08193 Bellaterra, Spain and Max Planck Institute for Astrophysics, Karl Schwarzschild Str. 1, Garching, D-85471, Germany arXiv:1208.5723v1 [astro-ph.SR] 28 Aug 2012 Key Words solar neutrinos, neutrino oscillations, solar models, helioseismol- ogy, nuclear astrophysics, metal abundances Abstract We describe the current status of solar neutrino measurements and of the theory { both neutrino physics and solar astrophysics { employed in interpreting measurements. Im- portant recent developments include Super-Kamiokande's determination of the ν e elastic − scattering rate for 8B neutrinos to 3%; the latest SNO global analysis in which the inclusion of 2 low-energy data from SNO I and II significantly narrowed the range of allowed values for the 7 neutrino mixing angle θ12; Borexino results for both the Be and pep neutrino fluxes, the first direct measurements constraining the rate of ppI and ppII burning in the Sun; global reanalyses of solar neutrino data that take into account new reactor results on θ13; a new decadal evalua- tion of the nuclear physics of the pp chain and CNO cycle defining best -

20 Years of Solar Neutrinos Since the First SNO Result

20 years of Solar Neutrinos since the first SNO result Art McDonald, Gray Chair in Particle Astrophysics, Emeritus Queen’s University, Kingston, Ontario, Canada For the SNO Collaboration Pioneers of Solar Neutrino Physics: Davis, Bahcall, Pontecorvo & Gribov 1968: Gribov and Pontecorvo suggest flavor 1968: Davis’ Measurements of electron neutrinos with change (oscillation) of Chlorine-based detector show 3 times fewer than electron neutrinos to muon Bahcall’s calculations. neutrinos as a possible Ray Davis: Nobel Laureate 2002 reason. Kamiokande, 1989 on 1968 on 2001 on 1992 on 1984: Herb Chen proposes heavy water to search for direct evidence of flavor transformation for neutrinos from 8B decay in the Sun. Electron neutrinos and all active neutrinos are measured separately to show flavor change independent of solar model calculations. SNO collaboration is created with Chen and George Ewan as Spokesmen. Unique Signatures in SNO (D2O) (1 in 6400 molecules in ordinary water are D2O. We used >99.75% D2O) Electron Neutrinos (CC) - νe+d → e +p+p Ethresh = 1.4 MeV Equal Sensitivity All Types (NC) νx+d → νx+n+p Ethresh = 2.2 MeV 3 ways to detect neutrons Comparing these two reactions tells if electron neutrinos have changed their type. Radioactivity must be carefully controlled because gamma rays can also break apart deuterium and produce a free neutron. Unique Signatures in SNO (D2O) (1 in 6400 molecules in ordinary water are D2O. We used >99.75% D2O) Electron Neutrinos (CC) - νe+d → e +p+p Ethresh = 1.4 MeV Equal Sensitivity All Types (NC) νx+d → νx+n+p Ethresh = 2.2 MeV 3 ways to detect neutrons Comparing these two reactions tells if electron neutrinos have changed their type. -

Members of the Division of Nuclear Physics, APS FROM: Benjamin F

TO: Members of the Division of Nuclear Physics, APS FROM: Benjamin F. Gibson, LANL – Secretary-Treasurer, DNP ACCOMPANYING THIS NEWSLETTER: Charles Glashausser, Rutgers, Vice Chair (2000) • APS Spring Meeting DNP Symposia Walter F. Henning, ANL, Past Chair (2000) • DNP Fall Meeting Speaker Nomination Form Benjamin F. Gibson, LANL, Secretary-Treasurer (2000) J. Dirk Walecka, College of William & Mary Divisional Councilor (December 2001) Christopher R. Gould, N. Carolina State Univ. (2000) Barry R. Holstein, U Mass (2001) Brian Serot, Indiana U (2000) T. James M. Symons, LBNL (2000) Robert E. Tribble, Texas A&M (2001) Future Deadlines Michael C. T. Wiescher, Notre Dame (2001) • 1 April 2000 — APS Fellowship Nominations • 4 May 2000 — Speaker Nominations for Fall Meeting 2. CALL FOR DNP COMMITTEE SUGGESTIONS • 1 July 2000 — Nominations for Bonner Prize • 1 July 2000 — Nominations for Bethe Prize The terms of some of the members of the following DNP committees • 1 July 2000 — Nominations for Dissertation Award expire in April 2000: Bethe, Bonner, Fellowship, Nominating, Home Page, and Education. Suggestions from the DNP membership for new members of these committees for 2000 are welcome and should be sent WWW Home Page for DNP - “http://www.phy.anl.gov/dnp/”. to Hamish Robertson. A list of committee members for 2000 will be published in the August newsletter. A worldwide web home page for the Division of Nuclear Physics is currently available at “http://www.phy.anl.gov/dnp/”. Information of interest to DNP members, such as current NP topics, deadlines for Inside . meetings, prizes, nomination forms, special announcements, and useful links are listed there. -

Stuart Freedman

2010 Decadal Review of NlNuclear Phys ics An Assessment and Outlook for Nuclear Physics Stuart J. Freedman, University of California, Berkeley, Chair Cherry Murray, Harvard University Ani Aprahamian, University of Notre Dame, Vice Chair Witold Nazarewicz, University of Tennessee Ricardo Alarcon, Arizona State University Konstantinos Orginos, College of William and Mary Gordon A. Baym, University of Illinois Krishna Rajagopal, MIT Elizabeth Beise, University of Maryland RGR.G. Hamish Robertson, University of Washington Richard F. Casten, Yale University Thomas J. Ruth, TRIUMF Jolie A. Cizewski, Rutgers Hendrik Schatz, National Superconducting Cyclotron Anna Hayes‐Sterbenz, Los Alamos National Laboratory Laboratory Roy J. Holt, Argonne National Laboratory Robert E. Tribble, Texas A&M University Karlheinz Langanke, GSI Helmholtz William A. Zajc, Columbia University Latest in the Series 1972 1986 1999 2012 100 years of Nuclear Physics Building the foundation for the future NP2010 Statement of Task 2007 NSAC Long Range Plan A five year plan organidized and formulated by the community through NSAC, advising DOE & NSF on science & development priorities in Nuclear Physics! Selecting organizing & writing committees Town meetings for sub‐communities NSAC meeting for entire community Write‐up of report Presentation of report to NSAC Presentation of report to agencies User Facilities CEBAF ATLAS RHIC • 4 National User Facilities • Approximately 40% of users are from foreign institutions • After completion FRIB will be a major National NSCL