Architectural, Sculptural, and Religious Change: a New Interpretation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

GAR 1923-24.Pdf

. o 2- REPORT OF THE ARCH^OLOGSCAL DEPARTMENT GWALIOR STATE. '" SAMVAT 1980 YEAR 1923-24. aWALIOR ALIJAH DARBAR PRESS, CONTENTS, PART i. Page, I. 1 Office Notes ... , ... t II. 2 Circulars and Orders . tt j at III. 3 Work Headquarters ... >t> ... IV. 4 Tours ... ... V. 5 Conservation Bagh ... ... ... Kanod ... ... ... Badoh ... ... ... Udaypur '... ... ... Narwar VI, Annual Upkeep ... VII, Exploration (a) Excavations .... ... ... (6) Listing of Monuments Amera or Murtizanagar ... ... # TJdaypur ... ... 's Sunari ~. ... " N Chirodia ... - * ... - - Badoh . lu Pathari - - *** * u II daygiri " ... li Chanderl . c> /-< - '" l " Goonn . - "" " Mohana . _ "" Knclibaua .., Satanwa<1a " *" "" Jharna , "* "" Piparia ... '** .^ *** "" Narwar ,- " "' VTIL Epigraphy "] *" *" ^ IX. Numismatics ... - '" *" j- Archaeological Museum X, '" ^ -.- '" XT. Copying of Bagh Frescoes ^ - *" "* XII. 4* Homc 1. 17 .- '" and Contributions XIII. Publications ''* ^ u and Drawings XIV. Photographs ^ lg "' "' .- Office Library t g XV. '*' XVI. Income and Expenditure ^^ XVIL Concluding Remarks 11 PART I L APPENDICES, Pago. 19 1. Appendix A Tour Diary ... ... ... 21 2. B Monuments conserved .. 3. C listed ... ... -. 22 ... ... ... 26 4. D Inscriptions . o. E Coins examined ... ... ... 32 6. F Antiquities added to Museum ... ... 33 7. G Copies of Bagh Frescoes ... ... 35 8. H Photographs ... .... ... 36 41 9. I Lantern Slides ... ... ... 10, J Drawings ... * ... 45 - 11. K Books ... ... -. 46 12." L Income ... ... ... 50 13. M Expenditure ... ... - ... 50 1 14. Illustrations ... ... - Plates to IV ANNUAL ADMINISTRATION REPORT OF THE ARCHAEOLOGICAL DEPARTMENT, GWALIOR STATE, FOR THE YEAR ENDING 30th JUNE 1924, SAMYAT 1980. PART I. Office Notes. Charge. During the year of report the undersigned held the charge of the Department except between the 1,9th of May and the 30th of June while he was on privilege leave. During the period of leave the charge of the current duties of the post remained with Mr- K, S. -

Final Report

Urban Administration and Development Department Government of Madhya Pradesh Consultancy Services for Preparation of City Development Plan for Bhind (Bhind District) Final Report Intercontinental Consultants and Technocrats Pvt. Ltd. A-8, Green Park, New Delhi - 110 016, India Project Co-ordinator : City Managers’ Association Madhaya Pradesh JUNE, 2011 City Development Plan for Bhind- Municipal Council TABLE OF CONTENTS S. No. Description Page no. List of Abbreviations Executive Summary 1.0 Introduction 1-1 To 1-9 1.1 Introduction 1-1 1.2 Background 1-1 1.3 Urbanisation as a phenomenon 1-2 1.3.1 Urbanization in India 1-2 to 1-3 1.3.2 Urbanization in Madhya Pradesh 1-3 1.4 City Development Plan 1-3 1.5 Purpose of Exercise 1-4 1.6 Expected Outcome of CDP 1-4 1.7 Methodology Adopted 1-4 1.7.1 Reconnaissance 1-4 1.7.2 Analysis of Existing Situation 1-5 1.7.3 Developing Vision for City 1-6 1.7.4 Development of strategies and priority actions 1-6 1.7.5 Developing a City Investment Plan and Financing Strategy 1.8 Meeting and consultations 1-8 1.9 Report structure 1-8 2.0 Physical and historical profile 2-1 to 2.8 2.1 Introduction 2-1 2.2 City in regional context 2-1 2.3 History of the town 2-2 to 2-4 2.4 Location and linkages 2-4 to 2-5 2.5 Physiography 26 2.5.1 Relief 2-6 2.5.2 River 2-6 2.5.3 Climate 2-6 Final CDP i City Development Plan for Bhind- Municipal Council S. -

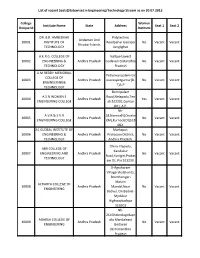

List of Vacant Seats(Statewise) in Engineering/Technology Stream As on 30.07.2015

List of vacant Seats(Statewise) in Engineering/Technology Stream as on 30.07.2015 College Women Institute Name State Address Seat 1 Seat 2 Unique Id Institute DR. B.R. AMBEDKAR Polytechnic Andaman And 10001 INSTITUTE OF Roadpahar Gaonpo No Vacant Vacant Nicobar Islands TECHNOLOGY Junglighat A.K.R.G. COLLEGE OF Nallajerlawest 10002 ENGINEERING & Andhra Pradesh Godavari Distandhra No Vacant Vacant TECHNOLOGY Pradesh A.M.REDDY MEMORIAL Petlurivaripalemnar COLLEGE OF 10003 Andhra Pradesh asaraopetguntur(D. No Vacant Vacant ENGINEERING& T)A.P TECHNOLOGY Burrripalam A.S.N.WOMEN S Road,Nelapadu,Ten 10004 Andhra Pradesh Yes Vacant Vacant ENGINEERING COLLEGE ali.522201,Guntur (Dt), A.P. Nh- A.V.R & S.V.R 18,Nannur(V)Orvaka 10005 Andhra Pradesh No Vacant Vacant ENGINEERING COLLEGE l(M),Kurnool(Dt)518 002. A1 GLOBAL INSTITUTE OF Markapur, 10006 ENGINEERING & Andhra Pradesh Prakasam District, No Vacant Vacant TECHNOLOGY Andhra Pradesh. China Irlapadu, ABR COLLEGE OF Kandukur 10007 ENGINEERING AND Andhra Pradesh No Vacant Vacant Road,Kanigiri,Prakas TECHNOLOGY am Dt, Pin 523230. D-Agraharam Villagerekalakunta, Bramhamgari Matam ACHARYA COLLEGE OF 10008 Andhra Pradesh Mandal,Near No Vacant Vacant ENGINEERING Badvel, On Badvel- Mydukur Highwaykadapa 516501 Nh- 214Chebrolugollapr ADARSH COLLEGE OF olu Mandaleast 10009 Andhra Pradesh No Vacant Vacant ENGINEERING Godavari Districtandhra Pradesh List of vacant Seats(Statewise) in Engineering/Technology Stream as on 30.07.2015 Valasapalli ADITYA COLLEGE OF Post,Madanapalle,C 10010 Andhra Pradesh No Vacant Vacant ENGINEERING hittoor Dist,Andhra Pradesh Aditya Engineering Collegeaditya Nagar, Adb Road, ADITYA ENGINEERING Surampalem,Gande 10011 Andhra Pradesh No Vacant Vacant COLLEGE palli Mandal, East Godavari District, Pin - 533 437, Andhra Pradesh. -

The Ancient Geography of India

CHARLES WILLIAM WASON COLLECTION CHINA AND THE CHINESE THE GIFT OF CHARLES WILLIAM WASON CLASS OF 1876 1918 Cornell University Library DS 409.C97 The ancient geqgraphv.of India 3 1924 023 029 485 f mm Cornell University Library The original of tliis book is in tine Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924023029485 THE ANCIENT GEOGRAPHY ov INDIA. A ".'i.inMngVwLn-j inl^ : — THE ANCIENT GEOGRAPHY INDIA. THE BUDDHIST PERIOD, INCLUDING THE CAMPAIGNS OP ALEXANDER, AND THE TRAVELS OF HWEN-THSANG. ALEXANDER CUNNINGHAM, Ui.JOB-GBirBBALj BOYAL ENGINEEBS (BENGAL BETIBBD). " Venun et terrena demoDstratio intelligatar, Alezandri Magni vestigiiB insistamns." PHnii Hist. Nat. vi. 17. WITS TSIRTBBN MAPS. LONDON TEUBNER AND CO., 60, PATERNOSTER ROW. 1871. [All Sights reserved.'] {% A\^^ TATLOB AND CO., PEIKTEES, LITTLE QUEEN STKEET, LINCOLN'S INN EIELDS. MAJOR-Q-ENEEAL SIR H. C. RAWLINSON, K.G.B. ETC. ETC., WHO HAS HIMSELF DONE SO MUCH ^ TO THROW LIGHT ON THE ANCIENT GEOGRAPHY OP ASIA, THIS ATTEMPT TO ELUCIDATE A PARTIODLAR PORTION OF THE SUBJKcr IS DEDICATED BY HIS FRIEND, THE AUTHOR. PEEFACE. The Geography of India may be conveniently divided into a few distinct sections, each broadly named after the prevailing religious and political character of the period which it embraces, as the Brahnanical, the Buddhist^ and the Muhammadan. The Brahmanical period would trace the gradual extension of the Aryan race over Northern India, from their first occupation of the Panjab to the rise of Buddhism, and would comprise the whole of the Pre- historic, or earliest section of their history, duiing which time the religion of the Vedas was the pre- vailing belief of the country. -

J825js4q5pzdkp7v9hmygd2f801.Pdf

INDEX S. NO. CHAPTER PAGE NO. 1. ANCIENT INDIA - 1 a. STONE AGE b. I. V. C c. PRE MAURYA d. MAURYAS e. POST MAURYAN PERIOD f. GUPTA AGE g. GUPTA AGE h. CHRONOLOGY OF INDIAN HISTORY 2. MEDIVAL INDIA - 62 a. EARLY MEDIEVAL INDIA MAJOR DYNASTIES b. DELHI SULTANATE c. VIJAYANAGAR AND BANMAHI d. BHAKTI MOVEMENT e. SUFI MOVEMENT f. THE MUGHALS g. MARATHAS 3. MODERN INDIA - 191 a. FAIR CHRONOLOGY b. FAIR 1857 c. FAIR FOUNDATION OF I.N.C. d. FAIR MODERATE e. FAIR EXTREMISTS f. FAIR PARTITION BENGAL g. FAIR SURAT SPLIT h. FAIR HOME RULE LEAGUES i. FAIR KHILAFAT j. FAIR N.C.M k. FAIR SIMON COMMISSION l. FAIR NEHRU REPORT m. FAIR JINNAH 14 POINT n. FAIR C.D.M o. FAIR R.T.C. p. FAIR AUGUST OFFER q. FAIR CRIPPS MISSION r. FAIR Q.I.M. s. FAIR I.N.A. t. FAIR RIN REVOLT u. FAIR CABINET MISSION v. MOUNTBATTEN PLAN w. FAIR GOVERNOR GENERALS La Excellence IAS Ancient India THE STONE AGE The age when the prehistoric man began to use stones for utilitarian purpose is termed as the Stone Age. The Stone Age is divided into three broad divisions-Paleolithic Age or the Old Stone Age (from unknown till 8000 BC), Mesolithic Age or the Middle Stone Age (8000 BC-4000 BC) and the Neolithic Age or the New Stone Age (4000 BC-2500 BC). The famous Bhimbetka caves near Bhopal belong to the Stone Age and are famous for their cave paintings. The art of the prehistoric man can be seen in all its glory with the depiction of wild animals, hunting scenes, ritual scenes and scenes from day-to-day life of the period. -

Common Service Centre (CSC) List (Madhya Pradesh State) List Received on 22 Dec 2018 from Rishi Sharma ([email protected]) for Ayushman Bharat-Madhya Pradesh

Common Service Centre (CSC) List (Madhya Pradesh State) List Received on 22 Dec 2018 from Rishi Sharma ([email protected]) for Ayushman Bharat-Madhya Pradesh SN District Subdistrict Po_Name Kiosk_Name Kiosk_Street Kiosk_Locality Pincode Kiosk_U/R 1 Agar Malwa Susner Agar Malwa S.O Shree Computer's Sunser ward no. 13 dak bangla main road 465441 Urban 2 Agar Malwa Agar Agar Malwa S.O Shankar Online & adhar center Ujjain road Agar Malwa 465441 Urban 3 Agar Malwa Agar Bapcha B.O SHREE COMPUTER DUG ROAD BAROD BAROD AGAR MALWA 465550 Urban 4 Agar Malwa Susner Susner S.O SHREE BALVEER COMPUTERS 96 465447 Urban 5 Agar Malwa Susner Susner S.O KAMAL KISHOR RAMANUJ RAMANUJ ONLINE CENTER BUS STAND SOYAT KALAN 465447 Urban 6 Agar Malwa Susner Susner S.O NEW LIFE COMPUTER TRAINING SCHOOL INDORE KOTA ROAD BUS STAND SOYAT KALAN 465447 Urban 7 Agar Malwa Badod Bapcha B.O Bamniya online Kiosk Barode Barode 465550 Urban 8 Agar Malwa Nalkheda Agar Malwa S.O GAWLI ONLINE CENTER JAWAHAR MARG 465441 Urban 9 Agar Malwa Agar Agar Malwa S.O basra online agar malwa agar malwa 465441 Urban 10 Agar Malwa Agar Agar Malwa S.O mevada online agar malwa agar malwa 465441 Urban 11 Agar Malwa Susner Susner S.O BHAWSAR SUSNER SUSNER 465447 Urban 12 Agar Malwa Susner Susner S.O Suresh Malviya Ward NO. 11 Hari Nagar Colony 465447 Urban 13 Agar Malwa Susner Susner S.O vijay jain itwariya bazar susner 465447 Urban 14 Agar Malwa Susner Susner S.O shailendra rajora shukrwariya bazar susner susner 465447 Urban 15 Agar Malwa Susner Susner S.O ARIHANT COMPUTER'S SHUKRAWARIYA -

195*+. I Proquest Number: 10731158

H I|S T O R I of the C A N D E' L L A S of JEJAKABHUKTI. by U.S. BOSE. (Uemai Sadhan Bose) ! Thesis submitted for examination for the dgree of Doctor of Philosophy at the University q London. 195*+. i ProQuest Number: 10731158 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10731158 Published by ProQuest LLC(2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 ■Synopsis« Subject0 History of the Oandellas of tJ'ejakabhukt 1B the history of the ^andellas was first traced by Smith in an article in l9o8 and then by Dr.H.C.Ray in a chapter of his Dynastic History of Northern India,Volume II,in 1936.These two scholars,;, gave only a very brief political history of the dynasty with cursury references to other aspects of Oandella history0This is the first effort to trace the full history of the Oandellas with the help of inscriptions,contemporary literary works, Moslem sources,monographs and a large number of articles with important bearing on the Oandellas.Besides the political history, I have discussed the administrative system,social,cultural -

Environment & Social Welfare Society, Khajuraho

ESW V Annual National Research Conference on 30 & 31 January, 2018 on Sustainable development of Ecosystem, Wildlife and Heritage conservation for Human welfare ESW V Annual National Research Conference On Sustainable development of Ecosystem, Wildlife and Heritage conservation for Human welfare 30 & 31 January, 2018 Organized By Environment & Social Welfare Society, Khajuraho An ISO 9001:2015 certified organization Dedicated to Environment, Education, Art and Science and Technology since Bi-Millennium. Under Govt. of MP., Firms & Society Act 1973 Reg. No. SC2707/2K Email: [email protected] Editor Dr. Ashwani Kumar Dubey (FIASc; FESW; FSLSc) Zoology, Ichthyology, Biochemistry, Free Radical Biology, Toxicology, Stress Monitoring, and Biodiversity In Association Bundelkhand Extended Region Chapter, Chitrakoot, National Academy of Sciences India Maharaja Chhatrasal Bundelkhand University, Chhatarpur MP Assisted by Godavari Academy of Science and Technology, Chhatarpur, Madhya Pradesh Website: http://www.godavariacademy.com ; Email: [email protected] Organized by: Environment and Social Welfare Society, Khajuraho, India Page 1 ESW V Annual National Research Conference on 30 & 31 January, 2018 on Sustainable development of Ecosystem, Wildlife and Heritage conservation for Human welfare About Environment & Social Welfare Society, Khajuraho Environment & Social Welfare Society (ESW Society) Dedicated to Environment, Education and Sciences & Technology entire India since bi-Millennium is an ISO 9001:2015 certified organization of the India. Now it’s worldwide known by its impact. ESW Society has been to develop relationship between Environment and Society envisions the promotion of Education and Sciences among the University, College and School students as well as in the society for Environment and Social welfare as well as Human Welfare. -

24 Part Xii-A Village and Town Directory

CENSUS OF INDIA 2011 MADHYA PRADESH SERIES -24 PART XII-A DISTRICT CENSUS HANDBOOK DATIA VILLAGE AND TOWN DIRECTORY DIRECTORATE OF CENSUS OPERATIONS MADHYA PRADESH 2011 I INDIA C F R MADHYA PRADESH ro m T T M a DISTRICT DATIA S u KILOMETRES I 4 2 0 4 8 12 16 D r ha d La .Bhin To f Dist Part oB R SEONDHA H ! R ( d O G hin Dist.B A f I I J Part o L N A ! ! 9 ! ! 1 ! ! r p u ! ! an ! t ! H a ! ! o R S ! ! D ! T W ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! G ! ! Tharet ! ! ! r ! !! ! a ! ! !! h ! a ! ! ! L ! ! ! o C . D . B L O C K ! BH ! T ! ! ! ! ! T ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! S E O N D H A ! ! ! ! ! C ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! I ! ! ! INDERGARH ! ! ! ! ! ! ! R ! . R ! ! j R ! u F . B h G R ! a T ! r J P w o h ! m d ! a n i ! S l S i ! o I r ! ! C . D!. B L O C K B H A N D E R ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! D ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! R ! ! ! ! C ! ! S ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !! ! ! ! ! ! !BH ! ! ! ! ! ! ! N ! !! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! H ! ! ! ! 7 ! 5 ! ! BHANDER ! ! ! ! ! H ! ( ! R ! ! ! ! ! C . D . B L O C K D A T I A ! ! ! J ! DATIA ! S r D ! wa ! ar BADONI ! N ! P ! om ! ! r ! F R G ! I S ! E ! ) E ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 9 ! ! 1 N ! ! R H ! ! H ! S ! ! ! 7 ! 5 ! T ! o D TAHSILS ! C ! U ! Unao h A SEONDHA i r g . INDERGARH a A B o T n P o C. BHANDER J h DATIA D a R Udgawan n s V i P TOTAL POPULATION 786,754 I N NUMBER OF TAHSILS 4 H 25 ri R Shivpu To Jhansi NUMBER OF C.D. -

Report of the Arch^Ologscal Department Gwalior State

. o 2- REPORT OF THE ARCH^OLOGSCAL DEPARTMENT GWALIOR STATE. '" SAMVAT 1980 YEAR 1923-24. aWALIOR ALIJAH DARBAR PRESS, CONTENTS, PART i. Page, I. 1 Office Notes ... , ... t II. 2 Circulars and Orders . tt j at III. 3 Work Headquarters ... >t> ... IV. 4 Tours ... ... V. 5 Conservation Bagh ... ... ... Kanod ... ... ... Badoh ... ... ... Udaypur '... ... ... Narwar VI, Annual Upkeep ... VII, Exploration (a) Excavations .... ... ... (6) Listing of Monuments Amera or Murtizanagar ... ... # TJdaypur ... ... 's Sunari ~. ... " N Chirodia ... - * ... - - Badoh . lu Pathari - - *** * u II daygiri " ... li Chanderl . c> /-< - '" l " Goonn . - "" " Mohana . _ "" Knclibaua .., Satanwa<1a " *" "" Jharna , "* "" Piparia ... '** .^ *** "" Narwar ,- " "' VTIL Epigraphy "] *" *" ^ IX. Numismatics ... - '" *" j- Archaeological Museum X, '" ^ -.- '" XT. Copying of Bagh Frescoes ^ - *" "* XII. 4* Homc 1. 17 .- '" and Contributions XIII. Publications ''* ^ u and Drawings XIV. Photographs ^ lg "' "' .- Office Library t g XV. '*' XVI. Income and Expenditure ^^ XVIL Concluding Remarks 11 PART I L APPENDICES, Pago. 19 1. Appendix A Tour Diary ... ... ... 21 2. B Monuments conserved .. 3. C listed ... ... -. 22 ... ... ... 26 4. D Inscriptions . o. E Coins examined ... ... ... 32 6. F Antiquities added to Museum ... ... 33 7. G Copies of Bagh Frescoes ... ... 35 8. H Photographs ... .... ... 36 41 9. I Lantern Slides ... ... ... 10, J Drawings ... * ... 45 - 11. K Books ... ... -. 46 12." L Income ... ... ... 50 13. M Expenditure ... ... - ... 50 1 14. Illustrations ... ... - Plates to IV ANNUAL ADMINISTRATION REPORT OF THE ARCHAEOLOGICAL DEPARTMENT, GWALIOR STATE, FOR THE YEAR ENDING 30th JUNE 1924, SAMYAT 1980. PART I. Office Notes. Charge. During the year of report the undersigned held the charge of the Department except between the 1,9th of May and the 30th of June while he was on privilege leave. During the period of leave the charge of the current duties of the post remained with Mr- K, S. -

Study on Bundelkhand CONTENTS Preface Acknowledgments Abbreviations Used Glossary of Terms Executive Summary

Study on Bundelkhand CONTENTS Preface Acknowledgments Abbreviations Used Glossary of Terms Executive Summary 1. Introduction 1.1 Origin of the state 1.2 Geographic Features 1.3 History 1.4 People and Administration 1.5 Caste, Religion and Language 1.6 Cultural Heritage 1.7 Political Scenario 2. Demography 2.1 Demographic - Characteristics 2.2 Inter - District Analysis 2.3 Nuptiality & Couple Protection Rate 2.4 Districtwise Analysis 3. Health 3.1 Government Infrastructure of Health Care Delivery 3.2 Health Care Aspects 3.3 Government Programmes on Health 4. Education 4.1 Factors Behind School Drop- Outs/Non- Enrollment and Educational Background 4.2 Rajiv Gandhi Shiksha Mission : State Effort in Education 5. Aspects of Economy 5.1 Agriculture 5.2 Forest and Animal Resources 5.3 Mining, Quarrying Industries 5.4 Poverty, Income and Quality of Life 5.5 Government Programmes for Rural Development / Self Employment 6. Government - Programmes For Rural Development 7. Voluntary Efforts In Bundelkhand Region 8. Concerns In Development : Issues For Action Annexure 1 Preface Madhya Pradesh is one of the front-runner states of India by publishing State Human Development Report analysing district level data on many pertinent parameters of development. Madhya Pradesh touches boundaries of 7 states therefore reflects excentuated regional tendencies of different socio-cultural and linguistic patterns. The analysis of Human Development of M.P. needs to be taken down upto the regional level.There is a dearth of studies reflecting status of development and disparities within the regions to promote micro level initiatives and people centred development. Bundelkhand in Madhya Pradesh is one of the underdeveloped regions which requires attention and efforts of development.