Three Ancient Sources: Gilgamesh, Hammurabi's Laws

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Republic of Iraq

Republic of Iraq Babylon Nomination Dossier for Inscription of the Property on the World Heritage List January 2018 stnel oC fobalbaT Executive Summary .......................................................................................................................... 1 State Party .......................................................................................................................................................... 1 Province ............................................................................................................................................................. 1 Name of property ............................................................................................................................................... 1 Geographical coordinates to the nearest second ................................................................................................. 1 Center ................................................................................................................................................................ 1 N 32° 32’ 31.09”, E 44° 25’ 15.00” ..................................................................................................................... 1 Textural description of the boundary .................................................................................................................. 1 Criteria under which the property is nominated .................................................................................................. 4 Draft statement -

CLEAR II Egyptian Mythology and Religion Packet by Jeremy Hixson 1. According to Chapter 112 of the

CLEAR II Egyptian Mythology and Religion Packet by Jeremy Hixson 1. According to Chapter 112 of the Book of the Dead, two of these deities were charged with ending a storm at the city of Pe, and the next chapter assigns the other two of these deities to the city of Nekhen. The Pyramid Texts describe these gods as bearing Osiris's body to the heavens and, in the Middle Kingdom, the names of these deities were placed on the corner pillars of coffins. Maarten Raven has argued that the association of these gods with the intestines developed later from their original function, as gods of the four quarters of the world. Isis was both their mother and grandmother. For 10 points, consisting of Qebehsenuef, Imsety, Duamutef, and Hapi, the protectors of the organs stored in the canopic jars which bear their heads, these are what group of deities, the progeny of a certain falconheaded god? ANSWER: Sons of Horus [or Children of Horus; accept logical equivalents] 2. According to Plutarch, the proSpartan Kimon sent a delegation with a secret mission to this deity, though he died before its completion, prompting the priest to inform his men that Kimon was already with this deity. Pausanias says that Pindar offered a statue of this god carved by Kalamis in Thebes and Pythian IV includes Medea's prediction that "the daughter of Epaphus will one day be planted... amid the foundations" of this god in Libya. Every ten days a cult statue of this god was transported to Medinet Habu in western Thebes, where he had first created the world by fertilizing the world egg. -

Gilgamesh Sung in Ancient Sumerian Gilgamesh and the Ancient Near East

Gilgamesh sung in ancient Sumerian Gilgamesh and the Ancient Near East Dr. Le4cia R. Rodriguez 20.09.2017 ì The Ancient Near East Cuneiform cuneus = wedge Anadolu Medeniyetleri Müzesi, Ankara Babylonian deed of sale. ca. 1750 BCE. Tablet of Sargon of Akkad, Assyrian Tablet with love poem, Sumerian, 2037-2029 BCE 19th-18th centuries BCE *Gilgamesh was an historic figure, King of Uruk, in Sumeria, ca. 2800/2700 BCE (?), and great builder of temples and ci4es. *Stories about Gilgamesh, oral poems, were eventually wriXen down. *The Babylonian epic of Gilgamesh compiled from 73 tablets in various languages. *Tablets discovered in the mid-19th century and con4nue to be translated. Hero overpowering a lion, relief from the citadel of Sargon II, Dur Sharrukin (modern Khorsabad), Iraq, ca. 721–705 BCE The Flood Tablet, 11th tablet of the Epic of Gilgamesh, Library of Ashurbanipal Neo-Assyrian, 7th century BCE, The Bri4sh Museum American Dad Gilgamesh and Enkidu flank the fleeing Humbaba, cylinder seal Neo-Assyrian ca. 8th century BCE, 2.8cm x 1.3cm, The Bri4sh Museum DOUBLING/TWINS BROMANCE *Role of divinity in everyday life. *Relaonship between divine and ruler. *Ruler’s asser4on of dominance and quest for ‘immortality’. StatuePes of two worshipers from Abu Temple at Eshnunna (modern Tell Asmar), Iraq, ca. 2700 BCE. Gypsum inlaid with shell and black limestone, male figure 2’ 6” high. Iraq Museum, Baghdad. URUK (WARKA) Remains of the White Temple on its ziggurat. Uruk (Warka), Iraq, ca. 3500–3000 BCE. Plan and ReconstrucVon drawing of the White Temple and ziggurat, Uruk (Warka), Iraq, ca. -

Hammurabi's Code

Hammurabi’s Code: Was It Just? Nearly 4,000 years ago, a man named Euphrates rivers. Hammurabi became king of a small city-state called Babylon. Today Babylon exists only as an After his victories at Larsa and Mari, archaeological site in central Iraq. But in Hammurabi's thoughts of war gave way to Hammurabi's time, it was the capital of the thoughts of peace. These, in turn, gave way to kingdom of Babylonia. thoughts of justice. In the 38th year of his rule, Hammurabi had 282 laws carved on a large, pillar- We know little about Hammurabi's like stone called a stele. Together, these laws have personal life. We don't know his birth date, how been called Hammurabi's Code. Historians believe many wives and children he had, or how and that several of these inscribed steles were placed when he died. We aren't even sure around the kingdom, though only what he looked like. However, one has been found intact. thanks to thousands of clay writing tablets that have been found by Hammurabi was not the first archaeologists, we know something Mesopotamian ruler to put his laws about Hammurabi's military into writing, but his code is the campaigns and his dealings with most complete. By studying his surrounding city-states. We also laws, historians have been able to know quite about every day life in get a good picture of many aspects Babylonia. of Babylonian society - work and family life, social structures, trade The tablets tell us that and government. For example, we Hammurabi ruled for 42 years. -

Neo Babylonian Rule

Neo Babylonians Rule “The Most Accomplished Empire” *Clears throat* Thank you. Thank you ever so much distinguished colleagues and professors for inviting me to speak to you today. As many of you know I'm professor Olivia Eichman of archeological studies at Stanford University. I have also worked at various dig sites in ancient sumers regions. All of these excavations lead me to countless degrees in antiquity. Enough about me already, I'm here to talk to you about about the great Mesopotamian Empires. But which empire was the greatest? Was it the Akkadians with the first empire? Or the Assyrians who reigned the longest? Neither of these empires strike me as the most accomplished. The Neo Babylonian’s Empire was the most accomplished empire by far and when you leave this room today I guarantee you will think as highly of them as I do too. Why do I think that the Neo Babylonians are the most accomplished? For starters, their ruler knew how to keep his empire safe. He had many safety precautions. One way Nebuchadrezzar II insured safety among his people was by surrounding their city in a wall so great in size two chariots could ride on it side by side. But that isn't all. No. Nebuchadnezzar II built another wall inside of the other wall for added protection. Both walls were named after Mesopotamian gods and goddesses. One of the gates that was built was called Ishtar gate, named after the goddess of war and love. To top it all off the walls were surrounded by a moat. -

The Evolution of Fragility: Setting the Terms

McDONALD INSTITUTE CONVERSATIONS The Evolution of Fragility: Setting the Terms Edited by Norman Yoffee The Evolution of Fragility: Setting the Terms McDONALD INSTITUTE CONVERSATIONS The Evolution of Fragility: Setting the Terms Edited by Norman Yoffee with contributions from Tom D. Dillehay, Li Min, Patricia A. McAnany, Ellen Morris, Timothy R. Pauketat, Cameron A. Petrie, Peter Robertshaw, Andrea Seri, Miriam T. Stark, Steven A. Wernke & Norman Yoffee Published by: McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research University of Cambridge Downing Street Cambridge, UK CB2 3ER (0)(1223) 339327 [email protected] www.mcdonald.cam.ac.uk McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research, 2019 © 2019 McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research. The Evolution of Fragility: Setting the Terms is made available under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivatives 4.0 (International) Licence: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ ISBN: 978-1-902937-88-5 Cover design by Dora Kemp and Ben Plumridge. Typesetting and layout by Ben Plumridge. Cover image: Ta Prohm temple, Angkor. Photo: Dr Charlotte Minh Ha Pham. Used by permission. Edited for the Institute by James Barrett (Series Editor). Contents Contributors vii Figures viii Tables ix Acknowledgements x Chapter 1 Introducing the Conference: There Are No Innocent Terms 1 Norman Yoffee Mapping the chapters 3 The challenges of fragility 6 Chapter 2 Fragility of Vulnerable Social Institutions in Andean States 9 Tom D. Dillehay & Steven A. Wernke Vulnerability and the fragile state -

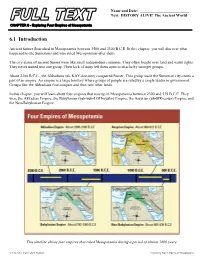

Text: HISTORY ALIVE! the Ancient World

Name and Date: _________________________ Text: HISTORY ALIVE! The Ancient World 6.1 Introduction Ancient Sumer flourished in Mesopotamia between 3500 and 2300 B.C.E. In this chapter, you will discover what happened to the Sumerians and who ruled Mesopotamia after them. The city-states of ancient Sumer were like small independent countries. They often fought over land and water rights. They never united into one group. Their lack of unity left them open to attacks by stronger groups. About 2300 B.C.E., the Akkadians (uh-KAY-dee-unz) conquered Sumer. This group made the Sumerian city-states a part of an empire. An empire is a large territory where groups of people are ruled by a single leader or government. Groups like the Akkadians first conquer and then rule other lands. In this chapter, you will learn about four empires that rose up in Mesopotamia between 2300 and 539 B.C.E. They were the Akkadian Empire, the Babylonian (bah-buh-LOH-nyuhn) Empire, the Assyrian (uh-SIR-ee-un) Empire, and the Neo-Babylonian Empire. This timeline shows four empires that ruled Mesopotamia during a period of almost 1800 years. © Teachers’ Curriculum Institute Exploring Four Empires of Mesopotamia Name and Date: _________________________ Text: HISTORY ALIVE! The Ancient World 6.2 The Akkadian Empire For 1,200 years, Sumer was a land of independent city-states. Then, around 2300 B.C.E., the Akkadians conquered the land. The Akkadians came from northern Mesopotamia. They were led by a great king named Sargon. Sargon became the first ruler of the Akkadian Empire. -

Egyptian Magic Publishers’ Note

S.V. JBooftg on Bagpt anft Cbalfta?a VOL. II. EGYPTIAN MAGIC PUBLISHERS’ NOTE. In the year 1894 Dr. Wallis Budge prepared for Messrs. Kegan Paul, Trench, Triibner & Co. an elementary work on the Egyptian language, entitled “First Steps in Egyptian,” and two years later the companion volume, “ An Egyptian Reading Book,” with transliterations of all the texts printed in it, and a full vocabulary. I he success of these works proved that they had helped to satisfy a want long felt by students of the Egyptian language, and as a similar want existed among students of the languages written in the cuneiform character, Mr. L. W. King, of the British Museum, prepared, on the same lines as the two books mentioned above, an elementary work on the Assyrian and Babylonian languages (“First Steps in Assyrian”), which appeared in 1898. These works, however, dealt mainly with the philological branch of Egyptology and Assyriology, and it was impossible in the space allowed to explain much that needed explanation in the other branches of these subjects—that is to say, matters relating to the archaeology, history, religion, etc., of the Egyptians, Assyrians, and Babylonians. In answer to the numerous requests which have been made, a series of short, popular handbooks on the most important branches of Egyptology and Assyriology have been prepared, and it is hoped that these will serve as introductions to the larger works on these subjects. The present is the second volume of the series, and the succeeding volumes will be published at short intervals, and at moderate prices. -

Fertile Crescent.Pdf

Fertile Crescent The Earliest Civilization! Climate Change … For Real. ➢ Climate not what it is like today. ➢ In Ancient times weather was good, the soil fertile and the irrigation system well managed, civilisation grew and prospered. ➢ Deforestation - The most likely cause of climate changing in the fertile crescent. ➢ Massive forest have their weather patterns. Ground temperature is lower. More biodiversity. Today vs. Ancient Times Map of the Fertile Crescent A day in the fertile crescent. Rivers Support the Growth of Civilization Near the Tigris and Euphrates Surplus Lead to Societal Growth Summary Mesopotamia’s rich, fertile lands supported productive farming, which led to the development of cities. In the next section you will learn about some of the first city builders. Where was Mesopotamia? How did the Fertile Crescent get its name? What was the most important factor in making Mesopotamia’s farmland fertile? Why did farmers need to develop a system to control their water supply? In what ways did a division of labor contribute to the growth of Mesopotamian civilization? How might running large projects prepare people for running a government? Early Civilizations By Rivers. Mesopotamia The land between the rivers. Religion: Great Ideas: Great Men: Geography: Major Events: Cultural Values: Structure of the Notes! Farming Lead to Division of Labor Although Mesopotamia had fertile soil, Farmers could produce a food surplus, or farming wasn’t easy there. The region more than they needed.Farmers also used received little rain.This meant that the water irrigation to water grazing areas for cattle and levels in the Tigris and Euphrates rivers sheep. -

Fate in Ancient Egypt

May Ahmed Hosny (JAAUTH), Vol. 19 No. 3, (2020), pp. 61-68. Fate in ancient Egypt May Ahmed Hosny Faculty of tourism and hotel management, Helwan University ARTICLE INFO Abstract Keywords: The Ancient Egyptian civilization is one of the richest Fate; Destiny; Shay; civilizations in acquiring various concepts and beliefs from last judgment; God’s nature. These concepts and beliefs can be divided into two will. categories Secular and Religious. As the ancient Egyptians were very religious people, so their dominant beliefs were (JAAUTH) religious beliefs which in turn had a great influence upon Vol. 19, No. 3, their secular life. Consequently, both concepts and beliefs (2020), were intermingling together. This paper will deal with a PP.61-68. unique topic which exists within the different thoughts and beliefs of every human being. No matter what was the time or the age this concept dominates the mind of every human being. Therefore, all the incidents that happens in our life will be automatically related to the fate concept which is stored in the thoughts and beliefs of the human mind. The Concept and its development In the ancient Egyptian language, the fate was known as: “ :SAy or : SAyt or SAw: meaning ordain or fix, which reflects the action of the divinities.(Wb IV 402, 8, 9) . The word “SAw” appeared since the end of the Old Kingdom till the late period, especially in the wisdom literature as for example the “Instruction of Ptahhotep” dating back to the 6th dynasty which stated “His time does not fail o come, one does not escape what is fated”. -

2-3-1: the First Empire Builders: Objective: Students Will Trace the Development of the First Empires in Mesopotamia, Akkad and Babylon

CHAPTER 2 Section 3: Empire of the Fertile Crescent 2-3-1: The First Empire Builders: Objective: Students will trace the development of the first empires in Mesopotamia, Akkad and Babylon. Introduction 1. Who fought for control of Mesopotamia from 3000 B.C. to 2000 B.C.? *Kings from different city-states. a. What factor allowed for such invasions? *The land was flat and easy to invade. b. What would one gain from controlling the region? *More land (more land means more wealth and power). 2. Despite the many efforts, how many rulers were able to control ALL of Mesopotamia? *None there were always some parts of Mesopotamia that were independent of the empire and could not be overtaken (its hard in ancient times to control large areaswe will see these struggles throughout the year). The Akkadian Empire: 3. Which ruler took control of Mesopotamia in 2371 B.C.? *Sargon (I) of Akkad a. What was this ruler known as? *Creator of the world’s first empire. How was he able to do this (Hint: think about the definition to # 4/5, the answer is not in your book)? *He conquered the many (12+) city-states of Sumer. 4. Define empire : *group of territories and peoples brought together under one supreme ruler (in this case the Sumerians under the rule of the Akkadians). 5. Define emperor : Person who rules an empire (Sargon I of Akkad) 6. Sargon’s empire was known as the ___ Empire. *Akkadian Empire 7. Define Fertile Crescent : *region stretching from the Persian Gulf through Mesopotamia to the Mediterranean Sea a. -

AHIS371 Egypt in the Old Kingdom S1 Day 2014

AHIS371 Egypt in the Old Kingdom S1 Day 2014 Ancient History Contents Disclaimer General Information 2 Macquarie University has taken all reasonable measures to ensure the information in this Learning Outcomes 3 publication is accurate and up-to-date. However, the information may change or become out-dated as a result of change in University policies, Assessment Tasks 3 procedures or rules. The University reserves the right to make changes to any information in this Delivery and Resources 6 publication without notice. Users of this publication are advised to check the website Unit Schedule 7 version of this publication [or the relevant faculty or department] before acting on any information in Policies and Procedures 9 this publication. Graduate Capabilities 10 Bibiographical Resources 15 Tips for Presentation and Essay 28 Topic Planner 31 https://unitguides.mq.edu.au/2014/unit_offerings/AHIS371/S1%20Day/print 1 Unit guide AHIS371 Egypt in the Old Kingdom General Information Unit convenor and teaching staff Department Administrator Raina Kim [email protected] Contact via [email protected] W6A 540 Unit Convenor Naguib Kanawati [email protected] Contact via [email protected] W6A 535 Wednesday 5-6pm Lecturer Joyce Swinton [email protected] Contact via [email protected] Credit points 3 Prerequisites 6cp at 200 level including (AHIS278 or AHST260) Corequisites Co-badged status Unit description The unit will examine the archaeological remains of the Egyptian Old Kingdom period from different sites. Art, architecture and material culture from funerary contexts will also be examined. Special emphasis will be given to understanding the administrative system and the daily life of the Egyptians in the period.