Arxiv:1603.05021V2 [Cond-Mat.Soft] 9 Nov 2017 Long-Range Hydrodynamic Interactions in 3D, Which Influence the Kinetics but Not the Equilibrium Behaviour [12–15]

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lecture Notes: BCS Theory of Superconductivity

Lecture Notes: BCS theory of superconductivity Prof. Rafael M. Fernandes Here we will discuss a new ground state of the interacting electron gas: the superconducting state. In this macroscopic quantum state, the electrons form coherent bound states called Cooper pairs, which dramatically change the macroscopic properties of the system, giving rise to perfect conductivity and perfect diamagnetism. We will mostly focus on conventional superconductors, where the Cooper pairs originate from a small attractive electron-electron interaction mediated by phonons. However, in the so- called unconventional superconductors - a topic of intense research in current solid state physics - the pairing can originate even from purely repulsive interactions. 1 Phenomenology Superconductivity was discovered by Kamerlingh-Onnes in 1911, when he was studying the transport properties of Hg (mercury) at low temperatures. He found that below the liquifying temperature of helium, at around 4:2 K, the resistivity of Hg would suddenly drop to zero. Although at the time there was not a well established model for the low-temperature behavior of transport in metals, the result was quite surprising, as the expectations were that the resistivity would either go to zero or diverge at T = 0, but not vanish at a finite temperature. In a metal the resistivity at low temperatures has a constant contribution from impurity scattering, a T 2 contribution from electron-electron scattering, and a T 5 contribution from phonon scattering. Thus, the vanishing of the resistivity at low temperatures is a clear indication of a new ground state. Another key property of the superconductor was discovered in 1933 by Meissner. -

Phase-Transition Phenomena in Colloidal Systems with Attractive and Repulsive Particle Interactions Agienus Vrij," Marcel H

Faraday Discuss. Chem. SOC.,1990,90, 31-40 Phase-transition Phenomena in Colloidal Systems with Attractive and Repulsive Particle Interactions Agienus Vrij," Marcel H. G. M. Penders, Piet W. ROUW,Cornelis G. de Kruif, Jan K. G. Dhont, Carla Smits and Henk N. W. Lekkerkerker Van't Hof laboratory, University of Utrecht, Padualaan 8, 3584 CH Utrecht, The Netherlands We discuss certain aspects of phase transitions in colloidal systems with attractive or repulsive particle interactions. The colloidal systems studied are dispersions of spherical particles consisting of an amorphous silica core, coated with a variety of stabilizing layers, in organic solvents. The interaction may be varied from (steeply) repulsive to (deeply) attractive, by an appropri- ate choice of the stabilizing coating, the temperature and the solvent. In systems with an attractive interaction potential, a separation into two liquid- like phases which differ in concentration is observed. The location of the spinodal associated with this demining process is measured with pulse- induced critical light scattering. If the interaction potential is repulsive, crystallization is observed. The rate of formation of crystallites as a function of the concentration of the colloidal particles is studied by means of time- resolved light scattering. Colloidal systems exhibit phase transitions which are also known for molecular/ atomic systems. In systems consisting of spherical Brownian particles, liquid-liquid phase separation and crystallization may occur. Also gel and glass transitions are found. Moreover, in systems containing rod-like Brownian particles, nematic, smectic and crystalline phases are observed. A major advantage for the experimental study of phase equilibria and phase-separation kinetics in colloidal systems over molecular systems is the length- and time-scales that are involved. -

Supercritical Fluid Extraction of Positron-Emitting Radioisotopes from Solid Target Matrices

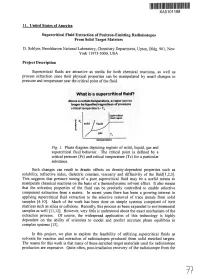

XA0101188 11. United States of America Supercritical Fluid Extraction of Positron-Emitting Radioisotopes From Solid Target Matrices D. Schlyer, Brookhaven National Laboratory, Chemistry Department, Upton, Bldg. 901, New York 11973-5000, USA Project Description Supercritical fluids are attractive as media for both chemical reactions, as well as process extraction since their physical properties can be manipulated by small changes in pressure and temperature near the critical point of the fluid. What is a supercritical fluid? Above a certain temperature, a vapor can no longer be liquefied regardless of pressure critical temperature - Tc supercritical fluid r«gi on solid a u & temperature Fig. 1. Phase diagram depicting regions of solid, liquid, gas and supercritical fluid behavior. The critical point is defined by a critical pressure (Pc) and critical temperature (Tc) for a particular substance. Such changes can result in drastic effects on density-dependent properties such as solubility, refractive index, dielectric constant, viscosity and diffusivity of the fluid[l,2,3]. This suggests that pressure tuning of a pure supercritical fluid may be a useful means to manipulate chemical reactions on the basis of a thermodynamic solvent effect. It also means that the solvation properties of the fluid can be precisely controlled to enable selective component extraction from a matrix. In recent years there has been a growing interest in applying supercritical fluid extraction to the selective removal of trace metals from solid samples [4-10]. Much of the work has been done on simple systems comprised of inert matrices such as silica or cellulose. Recently, this process as been expanded to environmental samples as well [11,12]. -

Phase Transitions in Quantum Condensed Matter

Diss. ETH No. 15104 Phase Transitions in Quantum Condensed Matter A dissertation submitted to the SWISS FEDERAL INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY ZURICH¨ (ETH Zuric¨ h) for the degree of Doctor of Natural Science presented by HANS PETER BUCHLER¨ Dipl. Phys. ETH born December 5, 1973 Swiss citizien accepted on the recommendation of Prof. Dr. J. W. Blatter, examiner Prof. Dr. W. Zwerger, co-examiner PD. Dr. V. B. Geshkenbein, co-examiner 2003 Abstract In this thesis, phase transitions in superconducting metals and ultra-cold atomic gases (Bose-Einstein condensates) are studied. Both systems are examples of quantum condensed matter, where quantum effects operate on a macroscopic level. Their main characteristics are the condensation of a macroscopic number of particles into the same quantum state and their ability to sustain a particle current at a constant velocity without any driving force. Pushing these materials to extreme conditions, such as reducing their dimensionality or enhancing the interactions between the particles, thermal and quantum fluctuations start to play a crucial role and entail a rich phase diagram. It is the subject of this thesis to study some of the most intriguing phase transitions in these systems. Reducing the dimensionality of a superconductor one finds that fluctuations and disorder strongly influence the superconducting transition temperature and eventually drive a superconductor to insulator quantum phase transition. In one-dimensional wires, the fluctuations of Cooper pairs appearing below the mean-field critical temperature Tc0 define a finite resistance via the nucleation of thermally activated phase slips, removing the finite temperature phase tran- sition. Superconductivity possibly survives only at zero temperature. -

Plasmofluidic Single-Molecule Surface-Enhanced Raman

ARTICLE Received 24 Feb 2014 | Accepted 9 Jun 2014 | Published 7 Jul 2014 DOI: 10.1038/ncomms5357 Plasmofluidic single-molecule surface-enhanced Raman scattering from dynamic assembly of plasmonic nanoparticles Partha Pratim Patra1, Rohit Chikkaraddy1, Ravi P.N. Tripathi1, Arindam Dasgupta1 & G.V. Pavan Kumar1 Single-molecule surface-enhanced Raman scattering (SM-SERS) is one of the vital applications of plasmonic nanoparticles. The SM-SERS sensitivity critically depends on plasmonic hot-spots created at the vicinity of such nanoparticles. In conventional fluid-phase SM-SERS experiments, plasmonic hot-spots are facilitated by chemical aggregation of nanoparticles. Such aggregation is usually irreversible, and hence, nanoparticles cannot be re-dispersed in the fluid for further use. Here, we show how to combine SM-SERS with plasmon polariton-assisted, reversible assembly of plasmonic nanoparticles at an unstructured metal–fluid interface. One of the unique features of our method is that we use a single evanescent-wave optical excitation for nanoparticle assembly, manipulation and SM-SERS measurements. Furthermore, by utilizing dual excitation of plasmons at metal–fluid interface, we create interacting assemblies of metal nanoparticles, which may be further harnessed in dynamic lithography of dispersed nanostructures. Our work will have implications in realizing optically addressable, plasmofluidic, single-molecule detection platforms. 1 Photonics and Optical Nanoscopy Laboratory, h-cross, Indian Institute of Science Education and Research, Pune 411008, India. Correspondence and requests for materials should be addressed to G.V.P.K. (email: [email protected]). NATURE COMMUNICATIONS | 5:4357 | DOI: 10.1038/ncomms5357 | www.nature.com/naturecommunications 1 & 2014 Macmillan Publishers Limited. All rights reserved. -

The Superconductor-Metal Quantum Phase Transition in Ultra-Narrow Wires

The superconductor-metal quantum phase transition in ultra-narrow wires Adissertationpresented by Adrian Giuseppe Del Maestro to The Department of Physics in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the subject of Physics Harvard University Cambridge, Massachusetts May 2008 c 2008 - Adrian Giuseppe Del Maestro ! All rights reserved. Thesis advisor Author Subir Sachdev Adrian Giuseppe Del Maestro The superconductor-metal quantum phase transition in ultra- narrow wires Abstract We present a complete description of a zero temperature phasetransitionbetween superconducting and diffusive metallic states in very thin wires due to a Cooper pair breaking mechanism originating from a number of possible sources. These include impurities localized to the surface of the wire, a magnetic field orientated parallel to the wire or, disorder in an unconventional superconductor. The order parameter describing pairing is strongly overdamped by its coupling toaneffectivelyinfinite bath of unpaired electrons imagined to reside in the transverse conduction channels of the wire. The dissipative critical theory thus contains current reducing fluctuations in the guise of both quantum and thermally activated phase slips. A full cross-over phase diagram is computed via an expansion in the inverse number of complex com- ponents of the superconducting order parameter (equal to oneinthephysicalcase). The fluctuation corrections to the electrical and thermal conductivities are deter- mined, and we find that the zero frequency electrical transport has a non-monotonic temperature dependence when moving from the quantum critical to low tempera- ture metallic phase, which may be consistent with recent experimental results on ultra-narrow MoGe wires. Near criticality, the ratio of the thermal to electrical con- ductivity displays a linear temperature dependence and thustheWiedemann-Franz law is obeyed. -

Density Fluctuations Across the Superfluid-Supersolid Phase Transition in a Dipolar Quantum Gas

PHYSICAL REVIEW X 11, 011037 (2021) Density Fluctuations across the Superfluid-Supersolid Phase Transition in a Dipolar Quantum Gas J. Hertkorn ,1,* J.-N. Schmidt,1,* F. Böttcher ,1 M. Guo,1 M. Schmidt,1 K. S. H. Ng,1 S. D. Graham,1 † H. P. Büchler,2 T. Langen ,1 M. Zwierlein,3 and T. Pfau1, 15. Physikalisches Institut and Center for Integrated Quantum Science and Technology, Universität Stuttgart, Pfaffenwaldring 57, 70569 Stuttgart, Germany 2Institute for Theoretical Physics III and Center for Integrated Quantum Science and Technology, Universität Stuttgart, Pfaffenwaldring 57, 70569 Stuttgart, Germany 3MIT-Harvard Center for Ultracold Atoms, Research Laboratory of Electronics, and Department of Physics, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, Massachusetts 02139, USA (Received 15 October 2020; accepted 8 January 2021; published 23 February 2021) Phase transitions share the universal feature of enhanced fluctuations near the transition point. Here, we show that density fluctuations reveal how a Bose-Einstein condensate of dipolar atoms spontaneously breaks its translation symmetry and enters the supersolid state of matter—a phase that combines superfluidity with crystalline order. We report on the first direct in situ measurement of density fluctuations across the superfluid-supersolid phase transition. This measurement allows us to introduce a general and straightforward way to extract the static structure factor, estimate the spectrum of elementary excitations, and image the dominant fluctuation patterns. We observe a strong response in the static structure factor and infer a distinct roton minimum in the dispersion relation. Furthermore, we show that the characteristic fluctuations correspond to elementary excitations such as the roton modes, which are theoretically predicted to be dominant at the quantum critical point, and that the supersolid state supports both superfluid as well as crystal phonons. -

Equation of State and Phase Transitions in the Nuclear

National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine Bogolyubov Institute for Theoretical Physics Has the rights of a manuscript Bugaev Kyrill Alekseevich UDC: 532.51; 533.77; 539.125/126; 544.586.6 Equation of State and Phase Transitions in the Nuclear and Hadronic Systems Speciality 01.04.02 - theoretical physics DISSERTATION to receive a scientific degree of the Doctor of Science in physics and mathematics arXiv:1012.3400v1 [nucl-th] 15 Dec 2010 Kiev - 2009 2 Abstract An investigation of strongly interacting matter equation of state remains one of the major tasks of modern high energy nuclear physics for almost a quarter of century. The present work is my doctor of science thesis which contains my contribution (42 works) to this field made between 1993 and 2008. Inhere I mainly discuss the common physical and mathematical features of several exactly solvable statistical models which describe the nuclear liquid-gas phase transition and the deconfinement phase transition. Luckily, in some cases it was possible to rigorously extend the solutions found in thermodynamic limit to finite volumes and to formulate the finite volume analogs of phases directly from the grand canonical partition. It turns out that finite volume (surface) of a system generates also the temporal constraints, i.e. the finite formation/decay time of possible states in this finite system. Among other results I would like to mention the calculation of upper and lower bounds for the surface entropy of physical clusters within the Hills and Dales model; evaluation of the second virial coefficient which accounts for the Lorentz contraction of the hard core repulsing potential between hadrons; inclusion of large width of heavy quark-gluon bags into statistical description. -

Generation and Stability of Size-Adjustable Bulk Nanobubbles

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Generation and Stability of Size-Adjustable Bulk Nanobubbles Based on Periodic Pressure Received: 10 September 2018 Accepted: 18 December 2018 Change Published: xx xx xxxx Qiaozhi Wang, Hui Zhao, Na Qi, Yan Qin, Xuejie Zhang & Ying Li Recently, bulk nanobubbles have attracted intensive attention due to the unique physicochemical properties and important potential applications in various felds. In this study, periodic pressure change was introduced to generate bulk nanobubbles. N2 nanobubbles with bimodal distribution and excellent stabilization were fabricated in nitrogen-saturated water solution. O2 and CO2 nanobubbles have also been created using this method and both have good stability. The infuence of the action time of periodic pressure change on the generated N2 nanobubbles size was studied. It was interestingly found that, the size of the formed nanobubbles decreases with the increase of action time under constant frequency, which could be explained by the diference in the shrinkage and growth rate under diferent pressure conditions, thereby size-adjustable nanobubbles can be formed by regulating operating time. This study might provide valuable methodology for further investigations about properties and performances of bulk nanobubbles. Nanobubbles are gaseous domains which could be found at the solid/liquid interface or in solution, known as surface nanobubbles (SNBs)1,2 and bulk nanobubbles (BNBs)3, respectively. For BNBs, generally recognized as spherical bubbles with the diameter of less than 1μm surrounded by liquid, though it has been observed frstly in 19814, the existence of long-lived BNBs is still a controversial subject as it is contrary to the classical theory5,6. -

Lecture 15: 11.02.05 Phase Changes and Phase Diagrams of Single- Component Materials

3.012 Fundamentals of Materials Science Fall 2005 Lecture 15: 11.02.05 Phase changes and phase diagrams of single- component materials Figure removed for copyright reasons. Source: Abstract of Wang, Xiaofei, Sandro Scandolo, and Roberto Car. "Carbon Phase Diagram from Ab Initio Molecular Dynamics." Physical Review Letters 95 (2005): 185701. Today: LAST TIME .........................................................................................................................................................................................2� BEHAVIOR OF THE CHEMICAL POTENTIAL/MOLAR FREE ENERGY IN SINGLE-COMPONENT MATERIALS........................................4� The free energy at phase transitions...........................................................................................................................................4� PHASES AND PHASE DIAGRAMS SINGLE-COMPONENT MATERIALS .................................................................................................6� Phases of single-component materials .......................................................................................................................................6� Phase diagrams of single-component materials ........................................................................................................................6� The Gibbs Phase Rule..................................................................................................................................................................7� Constraints on the shape of -

Phase Diagrams

Module-07 Phase Diagrams Contents 1) Equilibrium phase diagrams, Particle strengthening by precipitation and precipitation reactions 2) Kinetics of nucleation and growth 3) The iron-carbon system, phase transformations 4) Transformation rate effects and TTT diagrams, Microstructure and property changes in iron- carbon system Mixtures – Solutions – Phases Almost all materials have more than one phase in them. Thus engineering materials attain their special properties. Macroscopic basic unit of a material is called component. It refers to a independent chemical species. The components of a system may be elements, ions or compounds. A phase can be defined as a homogeneous portion of a system that has uniform physical and chemical characteristics i.e. it is a physically distinct from other phases, chemically homogeneous and mechanically separable portion of a system. A component can exist in many phases. E.g.: Water exists as ice, liquid water, and water vapor. Carbon exists as graphite and diamond. Mixtures – Solutions – Phases (contd…) When two phases are present in a system, it is not necessary that there be a difference in both physical and chemical properties; a disparity in one or the other set of properties is sufficient. A solution (liquid or solid) is phase with more than one component; a mixture is a material with more than one phase. Solute (minor component of two in a solution) does not change the structural pattern of the solvent, and the composition of any solution can be varied. In mixtures, there are different phases, each with its own atomic arrangement. It is possible to have a mixture of two different solutions! Gibbs phase rule In a system under a set of conditions, number of phases (P) exist can be related to the number of components (C) and degrees of freedom (F) by Gibbs phase rule. -

Phase Transitions in Multicomponent Systems

Physics 127b: Statistical Mechanics Phase Transitions in Multicomponent Systems The Gibbs Phase Rule Consider a system with n components (different types of molecules) with r phases in equilibrium. The state of each phase is defined by P,T and then (n − 1) concentration variables in each phase. The phase equilibrium at given P,T is defined by the equality of n chemical potentials between the r phases. Thus there are n(r − 1) constraints on (n − 1)r + 2 variables. This gives the Gibbs phase rule for the number of degrees of freedom f f = 2 + n − r A Simple Model of a Binary Mixture Consider a condensed phase (liquid or solid). As an estimate of the coordination number (number of nearest neighbors) think of a cubic arrangement in d dimensions giving a coordination number 2d. Suppose there are a total of N molecules, with fraction xB of type B and xA = 1 − xB of type A. In the mixture we assume a completely random arrangement of A and B. We just consider “bond” contributions to the internal energy U, given by εAA for A − A nearest neighbors, εBB for B − B nearest neighbors, and εAB for A − B nearest neighbors. We neglect other contributions to the internal energy (or suppose them unchanged between phases, etc.). Simple counting gives the internal energy of the mixture 2 2 U = Nd(xAεAA + 2xAxBεAB + xBεBB) = Nd{εAA(1 − xB) + εBBxB + [εAB − (εAA + εBB)/2]2xB(1 − xB)} The first two terms in the second expression are just the internal energy of the unmixed A and B, and so the second term, depending on εmix = εAB − (εAA + εBB)/2 can be though of as the energy of mixing.