The Dutch at the Helm – Navigating on a Rough Sea

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UNION NOW with BRITAIN, by Clarence K. Streit. Harper & Brothers, Publishers, New York, 1941

Louisiana Law Review Volume 4 | Number 1 November 1941 UNION NOW WITH BRITAIN, by Clarence K. Streit. Harper & Brothers, Publishers, New York, 1941. Pp. xv, 240. Jefferson B. Fordham Repository Citation Jefferson B. Fordham, UNION NOW WITH BRITAIN, by Clarence K. Streit. Harper & Brothers, Publishers, New York, 1941. Pp. xv, 240., 4 La. L. Rev. (1941) Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.lsu.edu/lalrev/vol4/iss1/27 This Book Review is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Reviews and Journals at LSU Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Louisiana Law Review by an authorized editor of LSU Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Book Reviews UNION Now WITH BRITAIN, by Clarence K. Streit. Harper & Brothers, Publishers, New York, 1941. Pp. xv, 240. Mr. Streit developed his idea of a federal union of national states before the war broke out. In 1939 he articulated it in Union Now, wherein he proposed that initially the union should be composed of fifteen democracies, namely, Australia, Belgium, Canada, Denmark, Eire, Finland, France, Holland, New Zealand, Norway, Sweden, Switzerland, the Union of South Africa, the United Kingdom, and the United States of America. Hitler has forced a revision of this scheme by overrunning five of the eight non-Englishspeaking countries in this group and isolating the remaining three. The present volume accordingly urges United States union now with the other Englishspeaking democracies. A common language, a predominantly common racial strain, and a common legal, political and cultural heritage are cohesive ele- ments that strongly favor the present lineup over the original plan. -

Statement by the Presidency of the WEU Permanent Council on the Termination of the Brussels Treaty (Brussels, 31 March 2010)

Statement by the Presidency of the WEU Permanent Council on the termination of the Brussels Treaty (Brussels, 31 March 2010) Caption: Statement made on 31 March 2010 by the Presidency of the Permanent Council of Western European Union (WEU) regarding the termination of the Modified Brussels Treaty and the closure of WEU (due to take place in June 2011). This statement follows the entry into force of the 2007 Treaty of Lisbon on 1 December 2009, particularly the mutual assistance clause between the Member States of the European Union (Article 42(7), EU Treaty). Source: Statement of the Presidency of the Permanent Council of the WEU on behalf of the High Contracting Parties to the Modified Brussels Treaty – Belgium, France, Germany, Greece, Italy, Luxembourg, The Netherlands, Portugal, Spain and the United Kingdom. Brussels: Western European Union, 31.03.2010. 2 p. http://www.weu.int/index.html. Copyright: (c) WEU Secretariat General - Secrétariat Général UEO URL: http://www.cvce.eu/obj/statement_by_the_presidency_of_the_weu_permanent_council_on_the_termination_of_the_bru ssels_treaty_brussels_31_march_2010-en-1ed29c90-5d6c-49f5-9886-48accc17dfbb.html Last updated: 22/06/2015 1 / 4 22/06/2015 WESTERN EUROPEAN UNION Statement of the Presidency of the Permanent Council of the WEU on behalf of the High Contracting Parties to the Modified Brussels Treaty – Belgium, France, Germany, Greece, Italy, Luxembourg, The Netherlands, Portugal, Spain and the United Kingdom Brussels, 31 March 2010 2 / 4 22/06/2015 3 / 4 22/06/2015 Statement of the Presidency of the Permanent Council of the WEU on behalf of the High Contracting Parties to the Modified Brussels Treaty – Belgium, France, Germany, Greece, Italy, Luxembourg, The Netherlands, Portugal, Spain and the United Kingdom The Western European Union has made an important contribution to peace and stability in Europe and to the development of the European security and defence architecture, promoting consultations and cooperation in this field, and conducting operations in a number of theatres, including Petersberg tasks. -

7 Justice for Janitors Goes Dutch

7 Justice for Janitors goes Dutch Precarious labour and trade union response in the cleaning industry (1988-2012): a transnational history* Abstract Precarious labour has been on the rise globally since the 1970s and 1980s. Changing labour relations in the cleaning industry are an example of these developments. From the 1970s onwards, outsourcing changed the position of industrial cleaners fundamentally: subcontracting companies were able to reduce labour costs by recruiting mainly women and immigrants with a weak position in the labour market. For trade unions, it was hard to find a way to counteract this tendency and to organize these workers until the Justice for Janitors (J4J) campaigns, set up by the us-based Service Employees International Union (seiu) from the late 1980s, showed that an adequate trade union response was possible. From the mid-2000s, the seiu launched a strategy to form international coalitions outside the United States. It met a favourable response in several countries. In the Netherlands, a campaign modelled on the J4J repertoire proved extraor- dinarily successful. In this chapter, transnational trade unionism in the cleaning industry based on the J4J model will be analysed with a special focus on the Dutch case. How were local labour markets and trade union actions related to the transnational connections apparent in the rise of multi-national cleaning companies, the immigrant workforce, and the role of the seiu in promoting international cooperation between unions? Keywords: outsourcing, precarious work, precariat, cleaners, janitors, organizing, transnationalism, regulatory unionism, industrial relations, The Netherlands * Reprinted from Ad Knotter, ‘Justice for Janitors Goes Dutch. Precarious Labour and Trade Union Response in the Cleaning Industry (1988-2012): A Transnational History’, International Review for Social History 62(1) (2017), 1-35. -

Paradoxes in Women's Conditions and Strategies in Swedish

Gothenburg University Publications Female Workers but not Women: Paradoxes in Women’s Conditions and Strategies in Swedish Trade Unions, 1900–1925 This is an author produced version of a paper published in: Moving the Social. Journal of social history and the history of social movements (ISSN: 2197-0386) Citation for the published paper: Uppenberg, C. (2012) "Female Workers but not Women: Paradoxes in Women’s Conditions and Strategies in Swedish Trade Unions, 1900–1925". Moving the Social. Journal of social history and the history of social movements, vol. 48 pp. 49-72. Downloaded from: http://gup.ub.gu.se/publication/221041 Notice: This paper has been peer reviewed but does not include the final publisher proof- corrections or pagination. When citing this work, please refer to the original publication. (article starts on next page) Social Movements in the Nordic Countries since 1900 49 Carolina Uppenberg links: Carolina Uppenberg rechts: Paradoxes in Women’s Conditions and Strate- Female Workers but not Women gies in Swedish Trade Unions Paradoxes in Women’s Conditions and Strategies in Swedish Trade Unions, 1900–1925 Abstract This article compares the opportunities that existed for trade union organisation by women and the scope for pursuing women’s issues in the Swedish Tailoring Workers’ Union (Skrädderiarbetareförbundet), the Swedish Textile Workers’ Union (Textilarbe- tareförbundet) and the Swedish Women’s Trade Union (Kvinnornas fackförbund). Trade union minutes are analysed using theories on women’s organisation, in which exposure of male standards in trade union organisation and the concept of women as powerless are central. The results reveal some differences in the opportunities for women to become members of the Tailoring Workers’ Union, which initially tried to exclude women, and the Textile Workers’ Union, which saw it as a priority to recruit more women. -

Transnationalizing a South African Domestic Workers' Union Moriah Elise Shumpert Old Dominion University

Old Dominion University ODU Digital Commons Institute for the Humanities Theses Institute for the Humanities Summer 2016 Collisions of Local and Global: Transnationalizing a South African Domestic Workers' Union Moriah Elise Shumpert Old Dominion University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.odu.edu/humanities_etds Part of the International Relations Commons, Labor Relations Commons, and the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Shumpert, Moriah E.. "Collisions of Local and Global: Transnationalizing a South African Domestic Workers' Union" (2016). Master of Arts (MA), thesis, Humanities, Old Dominion University, DOI: 10.25777/gm73-t237 https://digitalcommons.odu.edu/humanities_etds/5 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Institute for the Humanities at ODU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Institute for the Humanities Theses by an authorized administrator of ODU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. COLLISIONS OF LOCAL AND GLOBAL: TRANSNATIONALIZING A SOUTH AFRICAN DOMESTIC WORKERS’ UNION by Moriah Elise Shumpert B.A. December 2014, Old Dominion University A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Old Dominion University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS HUMANITIES OLD DOMINION UNIVERSITY August 2016 Approved by: Jennifer Fish (Director) David Earnest (Member) Erika Frydenlund (Member) ABSTRACT COLLISIONS OF LOCAL AND GLOBAL: TRANSNATIONALIZING A SOUTH AFRICAN DOMESTIC WORKERS’ UNION Moriah Elise Shumpert Old Dominion University, 2016 Director: Dr. Jennifer N. Fish This thesis explores how domestic worker trade unions’ functions have experienced a shift in their priorities as a result of the International Labor Organization’s (ILO) Convention 189, which standardizes rights for domestic workers worldwide. -

The Danish Referendum on Economic and Monetary Union

RESEARCH PAPER 00/78 The Danish Referendum 29 SEPTEMBER 2000 on Economic and Monetary Union Denmark obtained an opt-out from the third stage of Economic and Monetary Union as one of the conditions for agreeing to ratify the Treaty on European Union in 1993. Adoption of the euro would depend upon the approval of the electorate in a referendum. The Danes voted on 28 September to decide whether or not Denmark would join the single currency and replace the krone with the euro. The result was 53.1% to 46.9% against adopting the euro. This paper looks at the background to the Danish opt- out, the pro- and anti-euro campaigns, political and public attitudes towards the single currency and implications of the vote. Vaughne Miller INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS AND DEFENCE SECTION HOUSE OF COMMONS LIBRARY Recent Library Research Papers include: List of 15 most recent RPs 00/63 The Children Leaving Care Bill [HL] [Bill 134 of 1999-2000] 16.06.00 00/64 Unemployment by Constituency, May 2000 21.06.00 00/65 The Burden of Taxation 22.06.00 00/66 The Tourism Industry 23.06.00 00/67 Economic Indicators 30.06.00 00/68 Unemployment by Constituency, June 2000 12.07.00 00/69 Road Fuel Prices and Taxation 12.07.00 00/70 The draft Football (Disorder) Bill 13.07.00 00/71 Regional Social Exclusion Indicators 21.07.00 00/72 European Structural Funds 26.07.00 00/73 Regional Competitiveness & the Knowledge Economy 27.07.00 00/74 Cannabis 03.08.00 00/75 Third World Debt: after the Okinawa summit 08.08.00 00/76 Unemployment by Constituency, July 2000 16.08.00 00/77 Unemployment by Constituency, August 2000 13.09.00 Research Papers are available as PDF files: • to members of the general public on the Parliamentary web site, URL: http://www.parliament.uk • within Parliament to users of the Parliamentary Intranet, URL: http://hcl1.hclibrary.parliament.uk Library Research Papers are compiled for the benefit of Members of Parliament and their personal staff. -

Nordic Integration at the Cross-Road

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Lange, Gunnar Article — Digitized Version Nordic integration at the cross-road Intereconomics Suggested Citation: Lange, Gunnar (1969) : Nordic integration at the cross-road, Intereconomics, ISSN 0020-5346, Verlag Weltarchiv, Hamburg, Vol. 04, Iss. 10, pp. 306-309, http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/BF02926278 This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/138262 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. www.econstor.eu FORUM Nordic Integration at the Cross-Road The debate on a Scandinavian Economic Union has now entered its final stage. Pros and cons are subsequently reviewed by Denmark, Sweden and Norway. More Intra-Nordic Trade within a Customs Union Interview with Gunnar Lange, Swedish Minister of Commerce, Stockholm QUESTION: Mr Lange, dur- the organisations and institu- had, first before EFTA and then ing July of this year there has tions of our country. -

Book Reviews

BOOK REVIEWS The Brandywine. By HENRY SEIDEL CANBY. (New York: Farrar and Rinehart, Inc., 1941. xiii, 285 p. $2.50.) This is a pleasant book. It was doubtless a pleasure to its author to write, with its constant reminders of his youth. It is a pleasure to read, with its frequent glimpses of the sunny meadows and peaceful stretches of the modest Pennsylvania creek that has somehow been taken into the fraternity of the great streams that make up the main company of the "Rivers of America." Mr. Canby recognizes the boldness of this claim and argues for its propriety with ingenuity and good humor. He cites the commercial and industrial significance of the two miles of its course; the European versus the local usage of the term river; the acknowledged title of his subject to social, military and even literary fame. But after all to those of us who, like Mr. Canby, love the Brandywine, it is only one, though the longest and largest, of the five beautiful streams, Darby, Crum, Ridley, Chester and Brandywine, that make their way through the wooded hills from the higher lands of eastern Pennsylvania to the Delaware, after some six or seven hundred feet of fall and forty, fifty or sixty miles of length of course. If it is a river at all, all the implications of the term are on a small scale. Even the terrain of the Battle of Brandywine, the most notable event in its history, surprises the visitor with its small propor- tions. A region that stretches only from Chadds to Jeffries Ford, from Osborn Hill to Birmingham Meeting House, a stream that can be leaped over in some places and waded across everywhere except in a few backwaters, flanked for most of its course alternately by level meadows and open woods creates amazement that such a slight physical obstacle should be the deciding factor in a crucial battle of a continental war. -

What Do You Know? People, Places, and Cultures

NAME ________________________________________ DATE _____________ CLASS ______ Western Europe Lesson 3: Life in Western Europe ESSENTIAL QUESTION How do governments change? Terms to Know postindustrial describing an economy that is based on providing services rather than manufacturing What Do You Know? In the first column, answer the questions based on what you know before you study. After this lesson, complete the last column. Now… Later… How were the Western European nations able to recover following two world wars? How did Western European culture spread around the world? How has the economy of Western Europe evolved since World War II? People, Places, and Cultures Guiding Question What are contributions of Western Europe to Accessing Prior culture, education, and the arts? Knowledge Political events in the 1900s threatened all of Europe. In order to 1. What political events survive and compete in a changing world, the nations of Western in the 1900s made Europe needed to learn to work together. After World War II, they European countries made efforts to do this. believe they needed In April 1951, the Treaty of Paris created an international agency to work together? to supervise the coal and steel industries. France, West Germany, Belgium, the Netherlands, Luxembourg, and Italy signed this treaty. These six nations created the European Economic Community (the EEC) in 1958 to make trade among the member nations easier. Copyright © McGraw-Hill Education. Permission is granted to reproduce for classroom use. classroom for reproduce to is granted Permission Education. © McGraw-Hill Copyright Reading Essentials and Study Guide 153 NAME ________________________________________ DATE _____________ CLASS ______ Western Europe Lesson 3: Life in Western Europe, continued In 1967 these countries came together to form the European Sequencing Commission. -

For Union Now

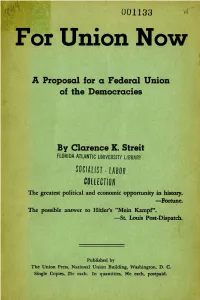

001133 For Union Now A Proposal for a Federal Union of the Democracies By Clarence K. Streit FLOR IDAATLANTI C.UNIVERSITY LIBRARY SOCI AUST - lABOR COUEGTlON The greatest political and economic opportunity in history. -Fortune. The possible answer to Hider's "Mein Kampf". -St. Louis Post-Dispatch. Published by The Union Press, National Union Building, Washington, D.C. Single Copies, 25c each. In quantities, We each, postpaid. Editorials and Reviews Washington (D. C.) Post: Those who read Mr. Streit's book will be im pressed with the logic and persuasiveness with which he meets many of the obvious criticisms that come to mind.... Here is a proposal, breath-taking but in no sense silly, to challenge fundamental thinking in our own and other democracies.... Resident for 10 years at the seat of the League of Nations, he watched the panorama there with the cool detachment of the first-class newspaperman and the objectivity of the Midwestern American who feels personally remote from Old-World frenzies. For Mr. Streit, while reared in Montana, is a native of Missouri, with all thereby implied. (Editorial.) Philadelphia Inquirer: Wars, rumors of war, threats of war; militarism, rearmament and back-breaking taxation; economic uncertainty and universal jitters - In the mind of virtually every man and woman today is the unanswered question: Can nothing be done to end these recurring terrors? ... Union Now • .. is one man's answer so daring in concept, so sweeping in its implications that it merits all the attention it will receive.... The idea of federated states is not fantastic. It is a reality spectacularly successful in our own country... -

The EEA Agreement and Norway's Other Agreements with the EU

Meld. St. 5 (2012–2013) Report to the Storting (White Paper) The EEA Agreement and Norway’s other agreements with the EU Translation from the Norwegian. For information only. Contents 1 Introduction ................................. 5 2.5.2 Norway’s participation in crisis 1.1 Purpose and scope ........................ 5 management and military 1.2 Norway’s cooperation with capacity building ........................... 33 the EU ............................................. 6 2.5.3 Dialogue and cooperation ............ 33 1.3 The content of the White Paper .. 8 2.6 Summary of actions the Government intends to take ......... 34 2 Norway’s options within the framework of its 3 Key priorities in Norway’s agreements with the EU ........... 9 European policy ......................... 36 2.1 Introduction .................................... 9 3.1 Norwegian companies and value 2.2 Early involvement in creation in the internal market .... 36 the development of policy 3.2 Key policy areas ............................. 37 and legislation ............................... 9 3.2.1 Labour relations and social 2.3 Management of welfare ............................................ 37 the EEA Agreement ...................... 11 3.2.2 Energy ............................................. 40 2.3.1 Assessment of EEA relevance ..... 12 3.2.3 The environment, climate 2.3.2 Possible adaptations when change and food safety .................. 42 incorporating new legal acts into 3.2.4 Cooperation on research the EEA Agreement ...................... 16 and education ................................. 44 2.3.3 Bodies with powers to make 3.2.5 Rural and regional policy .............. 46 decisions that are binding 3.2.6 Market access for Norwegian on authorities, companies or seafood ........................................... 48 individuals ....................................... 17 3.3 The Nordic countries and 2.3.4 The options available when Europe ........................................... -

LYRICS^" the Ihrliiiiinai'v "11"

'* r:p ~r^*pPW|^^"5S^'ry *5»7^j^~H 15^00 People* Scad the Every iWdty and SUMMIT RECORD FIFTIBTH YEAK. NO. 51 SUMMIT, N. J., TUESDAY AFTERNOON, FEBRUARY 21, 1939 $3.50 PER YEAR Troslow Talks Pass First Aid Course Director Reportp s on James Truslow Adams Provided By Red e Club Hears Work of Welfare Board Review of "Union Now'* . A. Groups Join ^ 27™"^ To Civic Group Sixteen Boy Scout leaden and "Disturbance of stability" and In- r Attend Camp Conference cky police and firemen computed Dean Morriss Talk Of much interest is James Trus- •N. Hamilton McGlffin, director of | stitutionaliiation of the chronically low Adams' review, of "Union Now" In Founders'Day Here Yesterday the first aid course sponsored by bv the local Y. M. ('. A. -Home-Vacation, Police Comtofener dives the Boy Scouts and the American ill were cited lo the Union County I Clarence K. Streit. published aa camp ami-Fred Dickeivson <vf the Red Cross. The course began No- of A. A. I). W. Gives Welfare Board Friday in the annual: £* fadind g article inl thhe Ne wY Yorkk t.. V staff are attending a camping ' Matt WHO StlOt WOflUUI !i*i! Booi k i! * Reasons for Majotaimug vember. 8th and ran for eleven sta- Broad Survey of Work report of Director Florence RJ £.•?** «evlew of February Cast of 175 Present Pag-conference at the .Newark Y.'Wl.' tions, losing only five of the origi- Slocum as the paramount hazards ('. A. today. This,-cohference -i.H to1 Here Saturday Night Numbers and Efficiency nal enrollment of twenty-one.