Agc Group: Advancing Toward Vision 2025

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Toyota, Nissan, Honda and Mitsubishi Agree to Joint Development of Charging Infrastructure for Phvs, Phevs and Evs in Japan

Toyota Motor Corporation Nissan Motor Co., Ltd. Honda Motor Co., Ltd. Mitsubishi Motors Corporation Toyota, Nissan, Honda and Mitsubishi Agree to Joint Development of Charging Infrastructure for PHVs, PHEVs and EVs in Japan TOKYO, Japan (July 29, 2013) – Toyota Motor Corporation, Nissan Motor Co., Ltd., Honda Motor Co., Ltd., and Mitsubishi Motors Corporation jointly announced their agreement to work together to promote the installation of chargers for electric-powered vehicles (PHVs, PHEVs, EVs*) and build a charging network service that offers more convenience to drivers in Japan. The move is in recognition of the critical need to swiftly develop charging infrastructure facilities to promote the use of electric-powered vehicles. Assisted by subsidies provided by the Japanese government, the four automakers will bear part of the cost to install the charging facilities. They will also work together to build a convenient and accessible charging network in collaboration with companies that are already providing charging services in which each of the four automakers already have a financial stake. At present, there are about 1,700 quick chargers and just over 3,000* normal chargers in Japan, which is generally recognized to be insufficient. In addition, the lack of sufficient coordination among existing charging providers can be improved to offer better charging service to customers. The government announced subsidies for installation of charging facilities totaling 100.5 billion yen as part of its economic policy for fiscal year 2013 to quickly develop the charging infrastructure and expand the use of electric-powered vehicles using alternative energy sources. Currently, each prefecture in Japan is drawing up a vision for the use of the subsidies. -

Glazing Systems Intelligence Service

Global light vehicle OE glazing market- forecasts to 2029 April 2015 SAMPLE Usage and copyright statement A single-user licenced publication is provided for individual use only. Therefore this publication, or any part of it, may not be copied, reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or be transmitted in any form by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior written permission of Aroq Limited. A multi-user licence edition can be freely and legally shared with your colleagues. This agreement includes sharing electronically via your corporate intranet or the making of physical copies for your company library. Excluded from this agreement is sharing any part of this publication with, or transmitting via any means to, anybody outside of your company. This content is the product of extensive research work. It is protected by copyright under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. The authors of Aroq Limited's research are drawn from a wide range of professional and academic disciplines. The facts within this study are believed to be correct at the time of publication but cannot be guaranteed. All information within this study has been reasonably verified to the author’s and publisher’s ability, but neither accept responsibility for loss arising from decisions based on this report. © 2015 All content copyright Aroq Limited. All rights reserved. If you would like to find out about our online multi-user services for your team or organisation, please contact: Mike Chiswell Senior QUBE Business Manager Tel: +44 (0)1527 573 608 Toll free from US: 1-866-545-5878 Email: [email protected] http://wwwS.just-auto.com/qube AMPLE April 2015 Page 2 This a sample PDF. -

Stock Information and Notes for Shareholders

Stock Information and Notes for Shareholders Stock Information (As of September 30, 2018) Notes for Shareholders Fiscal year From April 1 to March 31 of the following year Number of Shares Issued 3,310,097,492 Ordinary General June Note: Model AA Class Shares are included. Shareholders’ Meeting Number of Shareholders 618,205 Dividend payout Year-end dividend: March 31 confirmation date Interim dividend: September 30 Stock listings Japan: Tokyo and Nagoya Ownership Breakdown Overseas: New York and London (thousands of shares) Transfer agent Mitsubishi UFJ Trust and Banking Corporation Financial institutions Special account Mitsubishi UFJ Trust and Banking Corporation 1,142,293 Individuals, etc. management institution (including treasury stock) 34.51% Contact 1-1, Nikko-cho, Fuchu-shi, Tokyo, Japan 793,786 Japan Toll-Free: (0120)232-711 23.98% Mailing address Shin-Tokyo Post Office, PO box No.29, Tokyo 137-8081 Japan Mitsubishi UFJ Trust and Banking Corporation Corporate Agency Division Notice Other corporate Inquiries regarding change of registered address and requests entities Foreign corporate to purchase shares constituting less than one unit 679,787 entities and others (1) If you have an account with a securities company, please 20.54% 694,229 contact your securities company. 20.97% (2) If you do not have an account with a securities company Note: Ratio indicates the share of ownership to the total number of shares issued. and your shares are registered in special accounts, please contact Mitsubishi UFJ Trust and Banking Corporation. Major Shareholders (Top 10) Ratio of the number of Number of shares held to Name shares held the total number of (thousands) shares issued (excluding T-ROAD treasury stock) (%) You are invited to visit the Japan Trustee Services Bank, Ltd. -

Notification of Settlement on the Projects Conducted by Mitsubishi Hitachi Power Systems, Ltd

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Notification of Settlement on the Projects Conducted by Mitsubishi Hitachi Power Systems, Ltd. in the Republic of South Africa and Recognition of Extraordinary Loss on Unconsolidated Basis and Other Expenses on Consolidated Basis Tokyo, December 18, 2019 --- Hitachi, Ltd. (TSE: 6501, “Hitachi”) today announced that Hitachi and Mitsubishi Heavy Industries, Ltd. (“MHI”) have reached a settlement relating to a transfer of the boiler construction projects (the "Projects") in the Republic of South Africa conducted by Mitsubishi Hitachi Power Systems, Ltd. (“MHPS”), the joint venture company that integrated the respective thermal power generation system businesses of MHI and Hitachi, in conclusion of their discussion. 1. Circumstances of Settlement On March 31, 2016, Hitachi received from MHI a request for payments including part of amount to adjust business transfer price, etc. in connection with the project (collectively, the “Transfer Price Adjustment”)(1), and on January 31, 2017, MHI subsequently increased its claim amount for the Transfer Price Adjustment(2). On August 21, 2017, Hitachi received from the Japan Commercial Arbitration Association (the “JCAA”) the notice stating that MHI filed the request for arbitration with the JCAA on July 31, 2017 in order to claim for payment of 90,779 million ZAR (approximately 774.3 billion yen when converted at a rate of 8.53 yen to 1 ZAR) as the Transfer Price Adjustment(3). Hitachi and MHI have reached a settlement today as a result of discussion with sincerity and integrity in parallel with the arbitration. (1) “Ongoing Discussion on the projects of Mitsubishi Hitachi Power Systems, Ltd. in the Republic of South Africa” (announced on May 9, 2016) https://www.hitachi.com/New/cnews/month/2016/05/160509a.html (2) “Ongoing Discussion on the projects of Mitsubishi Hitachi Power Systems, Ltd. -

November 16, 2020 Mitsubishi Chemical's SMC Adopted for Roof of Toyota GR Yaris

November 16, 2020 Mitsubishi Chemical’s SMC Adopted for Roof of Toyota GR Yaris Mitsubishi Chemical Corporation Carbon fiber sheet molding compound (SMC) produced by Mitsubishi Chemical Corporation (MCC; Head office: Chiyoda-ku, Tokyo; President: Masayuki Waga) has been adopted for the roof of the new GR Yaris launched by Toyota Motor Corporation (Toyota; Head office: Toyota-shi, Aichi; President: Akio Toyoda) in September this year. Developed by MCC, this SMC is a type of intermediate material for carbon fiber reinforced plastics (CFRPs), and takes the form of a sheet-shaped material in which carbon fibers cut into several-centimeter lengths are dispersed in resin. The SMC can be processed into components in a short period of time, i.e., roughly two to five minutes, by press molding. In contrast to prepreg intermediate materials (uncut carbon fiber fabric impregnated with resin), this SMC features high formability for molding complicated shaped parts. Also, since the SMC’s mechanical properties are almost homogeneous, manufacturers can use carbon fiber with relative ease and achieve weight reduction and high strength while utilizing previously accumulated expertise in component design. Toyota adopted MCC’s SMC for the GR Yaris because it enables the automaker to achieve major weight reductions and high levels of component performance. Toyota also rated MCC’s SMC highly for its superior formability, which enables production of complicated shaped parts. This is the third round of Toyota vehicles that have used MCC’s SMC, following on from its adoption for the rear door frame of the Prius PHV in February 2017 and door and luggage room inner panels of the Lexus LC500 and LC500h luxury coupes in March 2017. -

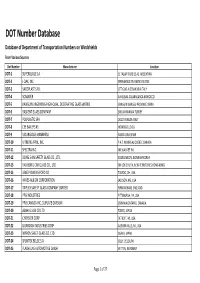

DOT Number Database Database of Department of Transportation Numbers on Windshields from Various Sources Dot Number Manufacturer Location DOT‐1 SUPERGLASS S.A

DOT Number Database Database of Department of Transportation Numbers on Windshields From Various Sources Dot Number Manufacturer Location DOT‐1 SUPERGLASS S.A. EL TALAR TIGRE BS.AS. ARGENTINA DOT‐2 J‐DAK, INC. SPRINGFIELD TN UNITED STATES DOT‐3 SACOPLAST S.R.L. OTTIGLIO ALESSANDRIA ITALY DOT‐4 SOMAVER AIN SEBAA CASABNLANCA MOROCCO DOT‐5 JIANGUIN JINGEHENG HIGH‐QUAL. DECORATING GLASS WORKS JIANGUIN JIANGSU PROVINCE CHINA DOT‐6 BASKENT GLASS COMPANY SINCAN ANKARA TURKEY DOT‐7 POLPLASTIC SPA DOLO VENEZIA ITALY DOT‐8 CEE BAILEYS #1 MONTEBELLO CA DOT‐9 VIDURGLASS MANBRESA BARCELONA SPAIN DOT‐10 VITRERIE APRIL, INC. P.A.T. MONREAL QUEBEC CANADA DOT‐11 SPECTRA INC. MILWAUKEE WI DOT‐12 DONG SHIN SAFETY GLASS CO., LTD. BOOKILMEON, JEONNAM KOREA DOT‐13 YAU BONG CAR GLASS CO., LTD. ON LOK CHUEN, NEW TERRITORIES HONG KONG DOT‐15 LIBBEY‐OWENS‐FORD CO TOLEDO, OH, USA DOT‐16 HAYES‐ALBION CORPORATION JACKSON, MS, USA DOT‐17 TRIPLEX SAFETY GLASS COMPANY LIMITED BIRMINGHAM, ENGLAND DOT‐18 PPG INDUSTRIES PITTSBURGH, PA, USA DOT‐19 PPG CANADA INC.,DUPLATE DIVISION OSHAWA,ONTARIO, CANADA DOT‐20 ASAHI GLASS CO LTD TOKYO, JAPAN DOT‐21 CHRYSLER CORP DETROIT, MI, USA DOT‐22 GUARDIAN INDUSTRIES CORP AUBURN HILLS, MI, USA DOT‐23 NIPPON SHEET GLASS CO. LTD OSAKA, JAPAN DOT‐24 SPLINTEX BELGE S.A. GILLY, BELGIUM DOT‐25 FLACHGLAS AUTOMOTIVE GmbH WITTEN, GERMANY Page 1 of 27 Dot Number Manufacturer Location DOT‐26 CORNING GLASS WORKS CORNING, NY, USA DOT‐27 SEKURIT SAINT‐GOBAIN DEUTSCHLAND GMBH GERMANY DOT‐32 GLACERIES REUNIES S.A. BELGIUM DOT‐33 LAMINATED GLASS CORPORATION DETROIT, MI, USA DOT‐35 PREMIER AUTOGLASS CORPORATION LANCASTER, OH, USA DOT‐36 SOCIETA ITALIANA VETRO S.P.A. -

Business Service Group

BUSINESS SERVICE GROUP The Business Service Group coordinates MC’s companywide from upstream to downstream, including consulting and IT strategies, covering everything from individual business system and IT infrastructure integration. Our comprehensive strategies to planning, development, and administration. services help to continuously raise the enterprise value of MC As the business climate trends toward diversity and Group companies and client companies, reform administrative globalization, and digital technology advances, the procedures, and develop operations. Furthermore, by importance of IT in corporate activity grows. There are now introducing and enhancing the most advanced and optimal greater demands to more effectively use IT as a tool for IT functions to respond to the enormous changes in IT needs, business expansion. we contribute to business expansion by boosting companies’ The Business Service Group provides integrated IT services competitive strength. BUSINESS SERVICE GROUP BUSINESS In order to help solve issues faced by MC Group companies and client companies, improve business processes and raise corporate value, the IT Service Business Division provides integrated IT services ranging from consulting to system development and operation, and IT outsourcing. We provide these services through business investments, or with the cooperation of business partners. We also work to expand and strengthen new IT-related businesses by supporting the introduction and deployment of advanced information technologies and uses for such technologies. IT Service Business ◦ Promotion of SI business and IT outsourcing business Division ◦ Promotion of consulting business and BPO business ◦ Support for businesses through advanced technologies and prior application experience ◦ Promotion of IT support and application for business investments both overseas (automobile business, Asian market, retail business) and Japan. -

COMPANY HANDBOOK 2020 Our Group at a Glance Who We Are Message from the Top Management Profile

COMPANY HANDBOOK 2020 Our Group at a glance Who We Are Message from the Top Management Profile Realizing Mitsubishi Chemical Holdings Corporation THE KAITEKI COMPANY Established October 3, 2005 Head office 1-1, Marunouchi 1-Chome, Chiyoda-ku, with a truly global Tokyo 100-8251, Japan recognition President Hitoshi Ochi Paid-in capital ¥50.0 billion In today’s society, we face a Listings Tokyo Stock Exchange range of issues: climate change, water shortages, resource and Activities Management of the Group companies (Development of Group strategies and energy issues, and increasing allocation of financial resources, etc.) medical costs associated with Business domains Performance Products, aging populations, to name a few. Meanwhile, scientific and Industrial Materials and Health Care technological developments are occurring at ever-faster Consolidated sales rates in areas such as information and communication revenue (IFRS) ¥3,580.5 billion technology (ICT), artificial intelligence (AI), robotics, mobility, Consolidated core medical and healthcare. These have the potential to bring operating income (IFRS) ¥194.8 billion about significant innovations. Number of employees Given this environment, we believe it is our mission to (consolidated) 69,609 bring together the innovation capabilities possessed by our Website https://www.mitsubishichem-hd.co.jp/english/ domestic and overseas group companies so that we can *All figures are for the year ended March 2020 (FY2019). continuously offer solutions to the above social problems. Financial Highlights (consolidated) Designating “Sustainability, Health and Comfort” as our (Unit: ¥billion) core values, we globally operate a wide range of businesses 4,250 380.5 400 grouped under three domains: Performance Products, 350 4,000 314.1 300.4 307.5 355.7 Industrial Materials and Health Care. -

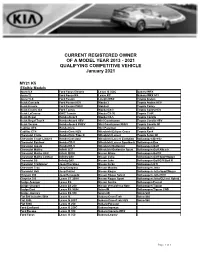

2021 QUALIFYING COMPETITIVE VEHICLE January 2021

CURRENT REGISTERED OWNER OF A MODEL YEAR 2013 - 2021 QUALIFYING COMPETITIVE VEHICLE January 2021 MY21 K5 Eligible Models Acura ILX Ford Focus Electric Lexus IS 350C Subaru WRX Acura TL Ford Focus RS Lexus RC Subaru WRX STI Acura TLX Ford Fusion Lincoln MKZ Toyota Avalon Buick Cascada Ford Fusion HEV Mazda 3 Toyota Avalon HEV Buick Encore Ford Fusion PHEV Mazda 6 Toyota Camry Buick Encore GX Ford Taurus Mazda CX-3 Toyota Camry HEV Buick LaCrosse GMC Terrain Mazda CX-30 Toyota C-HR Buick Regal Honda Accord Mazda CX-5 Toyota Corolla Buick Regal TourX Honda Accord HEV Mini Countryman Toyota Corolla HEV Buick Verano Honda Accord PHEV Mini Countryman PHEV Toyota Corolla iM Cadillac ATS Honda Civic Mini Paceman Toyota Matrix Cadillac CT4 Honda Civic HEV Mitsubishi Eclipse Cross Toyota Rav4 Chevrolet Cruze Honda Civic Type R Mitsubishi Lancer Toyota Scion iM Chevrolet Cruze Limited Honda Crosstour Mitsubishi Lancer Evolution Volkswagen Beetle Chevrolet Equinox Honda CR-V Mitsubishi Lancer Sportback Volkswagen Eos Chevrolet Impala Honda HR-V Mitsubishi Outlander Volkswagen Golf Chevrolet Malibu Infiniti G37 Mitsubishi Outlander Sport Volkswagen Golf Alltrack Chevrolet Malibu HEV Infiniti QX30 Nissan Altima Volkswagen Golf R Chevrolet Malibu Limited Infinity Q50 Nissan Cube Volkswagen Golf SportWagen Chevrolet SS Infinity Q60 Nissan Juke Volkswagen Golf/GTI/Golf R Chevrolet Trailblazer Jeep Cherokee Nissan Kicks Volkswagen GTI Chevrolet Trax Jeep Compass Nissan Maxima Volkswagen Jetta Chevrolet Volt Jeep Patriot Nissan Rogue Volkswagen Jetta SportWagen -

NGK SPARK PLUG and Mitsubishi Hitachi Power Systems Conclude

July 5, 2019 NGK SPARK PLUG CO., LTD. Mitsubishi Hitachi Power Systems, Ltd. NGK SPARK PLUG and Mitsubishi Hitachi Power Systems Conclude an Agreement for the establishment of a Joint Venture to Manufacture and Sell Fuel high-performance Cell Stacks Nagoya and Yokohama, July 5, 2019 – NGK SPARK PLUG CO., LTD. (NTK) and Mitsubishi Hitachi Power Systems, Ltd. (MHPS) have concluded an agreement regarding establishment of a joint venture and the operation of a company to manufacture and sell cylindrical cell stacks¹ as the power generating elements found in solid oxide fuel cells (SOFC)². Fuel cells are widely expected to be utilized as clean energy devices for commercial and industrial use, and are considered a solution for future energy and environmental issues. NTK and MHPS concluded a business partnership agreement in June 2014 for the mass production of cylindrical cell stacks, and of recent time, have been pursing joint development. The integration of NTK’s mass production technologies for ceramics and MHPS’ cylindrical cell stack design technologies, which allow for long life and heat utilization, has resulted in the commercial development of high-performance cylindrical cell stacks. Going forward, NTK will establish a preparatory company, with a joint venture company to be established following examination by competition authorities. □Outline of the JV Company (Planned) The two companies are currently in discussions for the joint venture. The following is the structure being considered at present. (1) Name TBD (2) Location Komaki, Aichi Prefecture (3) Representative TBD (4) Description of Business Manufacture and sale of cylindrical horizontal-stripe cell stacks (5) Capitalization 300 million yen (6) Investment Ratio NTK 70%, MHPS 30% (7) Start of Business October 1, 2019 1 / 3 Notes 1. -

Tips on Doing Business in Japan Yoshimitsu Khan Union College

Global Business Languages Volume 2 Cultures and Cross-Cultural Awareness in Article 16 the Professions May 2010 Tips on Doing Business in Japan Yoshimitsu Khan Union College Follow this and additional works at: http://docs.lib.purdue.edu/gbl Recommended Citation Khan, Yoshimitsu (2010) "Tips on Doing Business in Japan," Global Business Languages: Vol. 2 , Article 16. Available at: http://docs.lib.purdue.edu/gbl/vol2/iss1/16 Copyright © 2010 by Purdue Research Foundation. Global Business Languages is produced by Purdue CIBER. http://docs.lib.purdue.edu/gbl This is an Open Access journal. This means that it uses a funding model that does not charge readers or their institutions for access. Readers may freely read, download, copy, distribute, print, search, or link to the full texts of articles. This journal is covered under the CC BY-NC-ND license. Yoshimitsu Khan Union College TIPS ON DOING BUSINESS IN JAPAN This article was originally prepared for a meeting on international business practices held for General Electric Company executives and delivered at Union College. It is intended for American business men and women who have dealings with Japanese companies or other organiza- tions and have had very little or no experience with the culture and social mores of Japan. In order to emphasize the strictures of Japanese manners and etiquette, explanations are made concise and deliberately simple.* Though the problem of language differences presents an enourmous barrier, the problem of differences may present an obstacle just as im- posing. Japanese business protocol, behaviors, gestures, gesticulations, greetings, and etiquette are quite different from that of American or Western cultures. -

GLASTON CORPORATION Yliopistonkatu 7 - 00100 Helsinki - Finland Tel.: +358 10 500 500 / Fax: +358 10 500 6515

2015 world directory 2 - Copia omaggio € ââÊ`ÊV«iÀÌ>Ê > Suppliers’ THAT’S WHY THIS WILL BE Profiles YOUR NEXT LAMINATING LINE ZERO DEFECTS ZERO WASTE ZERO DOWNTIME > Suppliers’ ZERO DISPERSION Products & ÊÊ°ÊÓÇÉäÓÉÓää{ÊcÊ{È®Ê>ÀÌ°Ê£]ÊV>Ê£ÊÊ Ê>ÊÊÊUÊÊÊ*Ài Yellow Pages > Glassworks’ Addresses ÌÌ]Ê*ÃÌiÊÌ>>iÊ-«>ÊÊ-«i`°ÊÊ>°Ê«°ÊÊ °°ÊÎxÎÉÓääÎÊVÛ° Powerlam FLAT GLASS LAMINATING LINE WITH EVA & PVB AVAILABLE IN ABSOLUTE PERFORMANCE AND RELIABILITY INTERACTIVE VERSIONS TOO }ÞÊÌiÀ>Ì>]Ê->ÀÌiiÀ}ÞÊ-°À°°]Ê À°Ê,ië°Ê>ÀVÊ*i DESKTOP DISCOVER MORE www.rcnengineering.it IPAD/IPHONE RCN ENGINEERING S.R.L. Via Marcatutto, 7 - 20080 Albairate (MI) Italy Tel +39 02 94602434 - [email protected] www.rcnengineering.it -Õ««iiÌÊÊ>Ê°Ê£{{ÊÊ>ÀV É«ÀÊÊ°ÊÓÉÓä£xÊ`Ê>ÃÃ/iV ANDROID DEVICES www.glassonline.com Multi-roller coating machine for the enamelling and design printing of float glass sheets. ROLLMAC a division of GEMATA - Via Postale Vecchia, 77 - 36070 Trissino (VI) Italy Tel. +39.0445.490618 - Fax +39.0445.490639 - E-mail: [email protected] - www.rollmac.it Because we care Revolutionary. Also our technologies. INSULATING GLASS MANUFACTURING Bystronic glass symbolises innovation with machinery, HANDLING EQUIPMENT systems and services for the processing of architectural AUTOMOTIVE GLASS PREPROCESSING and automotive glass focused on tomorrow’s market. From basic requirements through to entire, customised installations Bystronic glass provides pioneering solutions – naturally, all in the highest quality. www.bystronic-glass.com IR medium wave twin tubes emitters for: iÃÊÌ>µÕ>ÀÌâÊ>ÃÊ«À`ÕViÃÊ } ÞÊ Ê UÊ >>Ì}Êià >««ÀiV>Ìi`Ê iµÕ«iÌÊ vÀÊ Ì iÊ }>ÃÃÊ Ê UÊ ÀÀÀ}Êià industry such as manual and au- Ê UÊ `ÀÞÊÃVÀiiÊ«ÀÌ}Êià tomatic tin side detectors and UV polymerization units.