SLEAC Report)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download Map (PDF | 2.37

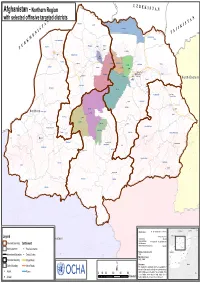

in te rn a tio n U a Z Khamyab l B Afghanistan - Northern Region E KIS T A N Qarqin with selected offinsive targeted districts A N Shortepa T N Kham Ab l a Qarqin n S o A i I t a n K T Shortepa r e t n S i JI I Kaldar N T A E Sharak Hairatan M Kaldar K Khani Chahar Bagh R Mardyan U Qurghan Mangajek Mangajik T Mardyan Dawlatabad Khwaja Du Koh Aqcha Aqcha Andkhoy Chahar Bolak Khwaja Du Koh Fayzabad Khulm Balkh Nahri Shahi Qaramqol Khaniqa Char Bolak Balkh Mazari Sharif Fayzabad Mazari Sharif Khulm Shibirghan Chimtal Dihdadi Nahri Shahi NorthNorth EasternEastern Dihdadi Marmul Shibirghan Marmul Dawlatabad Chimtal Char Kint Feroz Nakhchir Hazrati Sultan Hazrati Sultan Sholgara Chahar Kint Sholgara Sari Pul Aybak NorthernShirin Tagab Northern Sari Pul Aybak Qush Tepa Sayyad Sayyad Sozma Qala Kishindih Dara-I-Sufi Payin Khwaja Sabz Posh Sozma Qala Darzab Darzab Kishindih Khuram Wa Sarbagh Almar Dara-i-Suf Maymana Bilchiragh Sangcharak (Tukzar) Khuram Wa Sarbagh Sangcharak Zari Pashtun Kot Gosfandi Kohistanat (Pasni) Dara-I-Sufi Bala Gurziwan Ruyi Du Ab Qaysar Ruyi Du Ab Balkhab(Tarkhoj) Kohistanat Balkhab Kohistan Kyrgyzstan China Uzbekistan Tajikistan Map Doc Name: A1_lnd_eastern_admin_28112010 Legend CapitalCapital28 November 2010 Turkmenistan Jawzjan Badakhshan Creation Date: Kunduz Western WGS84 Takhar Western Balkh Projection/Datum: http://ochaonline.un.org/afghanistan Faryab Samangan Baghlan Provincial Boundary Settlement Web Resources: Sari Pul Nuristan Nominal Scale at A0 paper size: 1:640,908 Badghis Bamyan Parwan Kunar Kabul !! Maydan -

ASSESMENT REPORT of NEW IDPS in Jawzjan

ASSESMENT REPORT OF NEW IDPS IN Jawzjan INTRODUCTION This Report present the findings and observation from joint assessment of IDPs which has been conducted by ZOA together with ACTED and governmental department RRD, ANDMA, DoRR, Governor office and provincial council on October, 2017 in Jawzjan province, Afghanistan. The armed conflicts have increased in several districts of Faryab, Sar-e-Pul, and Jawzjan, thus creating new conflict IDPs in many areas. The number of conflict IDPs increased in 2017. During one month, October 2017 the 1314 families newly displaced from Faryab, Sar-e-Pul and from different districts of Jawzjan province in the villages around the Sheberghan city. Meanwhile the number IDPs are increasing day by day. Considering the increased number of IDPs, Governmental officials organized a meeting in Governor Office. NGOs and relevant governmental departments were invited in this meeting. Based on a decision in this meeting, a team of survey have been formed in order to find the number of new IDPs in Jawzjan province. The team was consist of 9 people from different governmental and non-governmental organizations. In addition to this assessment, DoRR department collected letters from IDPs’ families for assistance so, this report present the final number of IDPs specified and finalized by DoRR department. The aim of this assessment was to collect information about living condition of IDPs’ families who left their houses and all assets in their origin due to armed conflicts and displaced around the Centre of Jawjan province. METHODOLOGY Department of Returnees and Repatriation (DoRR) was leading the joint assessment. A team of 9 people including ZOA, ACTED, ANDMA, Police Department, provincial council and Governor Office representative, were assigned for this survey. -

Afghan Fiber Optic Ring

Islamic Republic of Afghanistan, Ministry of Communications and Information Technology (MCIT) Presentation by MCIT on Afghan Fiber Optic Ring International Conference, “Practical steps towards a knowledge-based economy” and the Seventh session of the SPECA Project Working Group on Knowledge-based Development Dushanbe,Tajikistan, 16-17 June 2015 CONTENTS: OFC CONNECTIVITY OF AFGHANISTAN; SYSTEMS/EQUIPMENT INSTALLED FOR OFC RING BACKBONE NETWORKS OF AFGHANISTAN; OFC NETWORK BANDWIDTH ALLOCATION; ROAD STATUS BETWEEN AFGHANISTAN AND CHINA THROUGH WAKHAN BORDER; ISSUES AND CHALLENGES OFC CONNECTIVITY OF AFGHANISTAN Under OFC Backbone Ring Project of Afghanistan [as funded by the Government under Core Development Budget of Afghanistan], 21 Provincial capitals have been connected and made operational for Broadband connectivity. These Provincial Capital cities/Provinces are as under: Kabul; Jalalabad ; Laghman; Logar; Paktia; Khost ; Paktika; Ghazni; Maidan Wardak; Qalat; Kandahar ; Lashkargah; Heraat ; Maimana ; Sheberghan; Mazaar-e-sharief ; Aibak; Pulekhumri; Kundoz , Parwan and Takhar . Another 04 Provinces will be connected with the Backbone Network in 2015-16, under the World Bank fund: Bamiyan, Badakshan; Kapisa and Kunar; Afghanistan needs (USD 40 Million )funds to connect the remaining 09 Provinces: Farah; Panjsheer; Sarepul; Qalaienow; Zaranj; Daikundi; Chagcharan; Tarinkot and Nuristan. OFC INTERNATIONAL CONNECTIVITY OF AFGHANISTAN. International connectivity has been established with Pakistan at two points – Turkham and Spin Boldak; with Tajikistan at Sherkhan Bandar; with Uzbekistan at Hayratan; with Turkmenistan at Aqina and Turghundi and with Iran at Islam Qala. Due to Security Issues, Ring is not complete due to a Gap in Connectivity between Heraat and Maimana ; Once this Gap is covered, the Backbone will have better Reliability and Redundancy in routing of Traffic. -

IT in Afghanistan

ICT in Afghanistan (two-way communication only) Siri Birgitte Uldal Muhammad Aimal Marjan 4. February 2004 Title NST report ICT in Afghanistan (Two way communication only) ISBN Number of pages Date Authors Siri Birgitte Uldal, NST Muhammad Aimal Marjan, Ministry of Communcation / Afghan Computer Science Association Summary Two years after Taliban left Kabul, there is about 172 000 telephones in Afghanistan in a country of assumed 25 mill inhabitants. The MoC has set up a three tier model for phone coverage, where the finishing of tier one and the start of tier two are under implementation. Today Kabul, Herat, Mazar-i-Sharif, Kandahar, Jalalabad, Kunduz has some access to phones, but not enough to supply the demand. Today there are concrete plans for extension to Khost, Pulekhomri, Sheberghan, Ghazni, Faizabad, Lashkergha, Taloqan, Parwan and Baglas. Beside the MoCs terrestrial network, two GSM vendors (AWCC and Roshan) have license to operate. The GoA has a radio network that reaches out to all provinces. 10 ISPs are registered. The .af domain was revitalized about a year ago, now 138 domains are registered under .af. Public Internet cafes exists in Kabul (est. 50), Mazar-i-Sharif (est. 10), Kandahar (est. 10) and Herat (est. 10), but NGOs has set up VSATs also in other cities. The MoC has plans for a fiber ring, but while the fiber ring may take some time, VSAT technology are utilized. Kabul University is likely offering the best higher education in the country. Here bachelor degrees in Computer Science are offered. Cisco has established a training centre in the same building offering a two year education in networking. -

Länderinformationen Afghanistan Country

Staatendokumentation Country of Origin Information Afghanistan Country Report Security Situation (EN) from the COI-CMS Country of Origin Information – Content Management System Compiled on: 17.12.2020, version 3 This project was co-financed by the Asylum, Migration and Integration Fund Disclaimer This product of the Country of Origin Information Department of the Federal Office for Immigration and Asylum was prepared in conformity with the standards adopted by the Advisory Council of the COI Department and the methodology developed by the COI Department. A Country of Origin Information - Content Management System (COI-CMS) entry is a COI product drawn up in conformity with COI standards to satisfy the requirements of immigration and asylum procedures (regional directorates, initial reception centres, Federal Administrative Court) based on research of existing, credible and primarily publicly accessible information. The content of the COI-CMS provides a general view of the situation with respect to relevant facts in countries of origin or in EU Member States, independent of any given individual case. The content of the COI-CMS includes working translations of foreign-language sources. The content of the COI-CMS is intended for use by the target audience in the institutions tasked with asylum and immigration matters. Section 5, para 5, last sentence of the Act on the Federal Office for Immigration and Asylum (BFA-G) applies to them, i.e. it is as such not part of the country of origin information accessible to the general public. However, it becomes accessible to the party in question by being used in proceedings (party’s right to be heard, use in the decision letter) and to the general public by being used in the decision. -

Livelihoods Zoning “Plus” Activity in Afghanistan

LIVELIHOODS ZONING “PLUS” ACTIVITY IN AFGHANISTAN A SPECIAL REPORT BY THE FAMINE EARLY WARNING SYSTEMS NETWORK (FEWS NET) February 2011 1 LIVELIHOODS ZONING “PLUS” ACTIVITY IN AFGHANISTAN A SPECIAL REPORT BY THE FAMINE EARLY WARNING SYSTEMS NETWORK (FEWS NET) February 2011 The authors’ views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development or the United States Government. 2 Contents Acknowledgments ......................................................................................................................................................... 5 Introduction ................................................................................................................................................................... 5 Methodology ................................................................................................................................................................. 7 Livelihoods Highlights .................................................................................................................................................... 8 National Seasonal Calendar ........................................................................................................................................... 9 Livelihood Zone 1: Eastern Mixed Agriculture and Forest ........................................................................................... 10 Livelihood Zone 2: Eastern Agro-Pastoral and Forest ................................................................................................ -

FOIA Request, Afghan Mass Grave, June 2006

June 21, 2006 Margaret P. Grafeld Robert Dickerson Director, Office of IRM Programs and Freedom of Information and Privacy Services, SA-2 Acts Division, US Army 5th Floor Attn: AHRC-PDD-FP US Department of State 7701 Telegraph Road Washington, D.C. 20522-6001 Alexandria, VA 22315-3860 Fax number: (202) 261-8579 Fax number: (703) 428-6522 Karen M. Finnegan U.S. Central Command Office of Freedom of Information CCJ6-DM (FOIA) 1155 Defense Pentagon 7115 South Boundary Blvd Washington, D.C. 20301-1155 MacDill AFB, FL 33621-5510 Fax number: (703) 696-4506 Fax number: (813) 827-5342 John Espinal Information and Privacy Coordinator 11 CS/SCS (FOIA) Central Intelligence Agency 1000 Air Force Pentagon Washington, D.C. 20505. Washington, D.C. 20330-1000 Fax number: (703) 613-3007 Fax number: (703) 696-7273 Request Submitted Under the Freedom of Information Act Dear FOIA Officer, This letter is a Request under the Freedom of Information Act, 5 U.S.C. § 552 (FOIA), submitted on behalf of Physicians for Human Rights (PHR). We are filing the Request simultaneously with the Department of Defense (including the Department of the Air Force, the Department of the Navy, and U.S. Central Command), the Department of State (including the War Crimes Office), and the Central Intelligence Agency. The Request relates to a mass grave at Dasht-e-Leili in Afghanistan, allegedly the burial site for hundreds of surrendered Taliban fighters. Our Request is based on international news reports and investigations from January 2002 to February 2004 that indicate that the bodies of as many as 2,000 Taliban fighters may lie in the mass grave at Dasht-e-Leili. -

Part III Description of River Basins

PART III DESCRIPTION OF RIVER BASINS Picture 38 Two different worlds separated by only a river; on the right bank of the Murghab river, ‘kuchi’ nomad tents in Afghanistan, on the left bank, a cooperative in Turkmenistan. Water is largely unused on the Afghan side. Murichak, Bala Murghab, 21 May 2003 (N35.72, E, 63.19, NW) 62 I. MAPS AND STATISTICS BY RIVER BASIN The map 8 shows the boundaries of the five River Basins delineated for Afghanistan: 1. The Amu Darya River Basin 2. The Northern River Basin 3. The Harirod-Murghab River Basin 4. The Hilmand River Basin 5. The Kabul (Indus) River Basin For each river basin, source of water, transboundaries riparian issues, natural resources, protected areas, land cover, type of agriculture, hydrological infrastructures (dams) and main historical development along water sources are summarized and whenever possible illustrated with pictures. The tables 8, 9 and 10 present statistics on area, population and the main land cover features by river basin. The graph 9 shows that the largest of these 5 basins is the Hilmand basin as it covers alone 43% of the national territory. The other 4 basins have similar size and represent 10 to 14% of the country. In additions to these river basins, there are 4 none drainage areas, namely Namaksar, Registan-i Sedi, Registan and Dasth-i Shortepa. The graph on Map 8 shows that 57% of the total river flow in Afghanistan originates from the Amu Darya River Basin. The Kabul (Indus) and Hilmand River Basins contributes respectively to 26 and 11% of the total water flow. -

Jawzjan Province of Afghanistan from 12Th to 22Nd of April 2012

SMART nutrition assessment report Report of Nutrition and Mortality in Jawzjan province of Afghanistan from 12th to 22nd of April 2012. (28th April 2012) Óscar Serrano Oria, Nutrition ERP, SCUK Dr. Mohammad Akbar Sabawoon, Senior Nutrition Manager, SC Afghanistan TABLE OF CONTENTS ACRONYMS .................................................................................... 3 Executive summary .......................................................................... 4 1. Introduction ............................................................................... 5 1.1 Survey Objectives ....................................................................... 6 2. Methodology ............................................................................... 7 2.1 Sample size ............................................................................... 7 2.2 Sampling procedure: selecting clusters .............................................. 9 2.3 Sampling procedure: selecting households and children .......................... 9 2.4 Case definitions and inclusion criteria ............................................. 10 2.5 Questionnaire, training and supervision ........................................... 11 2.6 Data analysis ........................................................................... 12 2.6 Limitations of the Survey ............................................................ 13 3. Results .................................................................................... 14 3.1 Anthropometric results (based on WHO standards -

Afghanistan Opium Survey 2020: Cultivation and Production

Islamic Republic of Afghanistan Afghanistan Opium Survey 2020 Cultivation and Production ‒ Executive Summary APRIL 2021 Research Page intentionally left blank Afghanistan Opium Survey 2020 – Executive Summary Introduction This Executive Summary presents the key findings of the Afghanistan Opium Survey 2020. The survey is implemented by NSIA in collaboration with UNODC. The survey team collects and analyses information on the location and extent of opium poppy cultivation, potential opium production and the socio-economic situation in rural areas. This information is essential for planning, implementing and monitoring counter-narcotic efforts. The opium survey is implemented within the technical framework of the UNODC Illicit Crop Monitoring Programme (ICMP), established in 1999 upon request of the Commission on Narcotic Drugs in its resolution 42/3, Monitoring and verification of illicit cultivation. The objective of ICMP is to assist the international community in monitoring the extent and evolution of illicit crops and to compile reliable and internationally comparable data. Currently, UNODC carries out monitoring activities in seven countries affected by illicit crop cultivation: coca surveys in Bolivia, Colombia and Peru; opium poppy surveys in Afghanistan, Mexico and Myanmar; and a cannabis survey in Nigeria. The Afghanistan Opium Survey 2020 was implemented under the project “Monitoring of Opium Production in Afghanistan” (AFG/F98), with financial contributions from the Government of United States of America. 3 Afghanistan Opium -

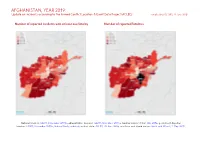

AFGHANISTAN, YEAR 2019: Update on Incidents According to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) Compiled by ACCORD, 29 June 2020

AFGHANISTAN, YEAR 2019: Update on incidents according to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) compiled by ACCORD, 29 June 2020 Number of reported incidents with at least one fatality Number of reported fatalities National borders: GADM, November 2015b; administrative divisions: GADM, November 2015a; Kashmir border status: CIA, 2004; geodata of disputed borders: GADM, November 2015b; Natural Earth, undated; incident data: ACLED, 20 June 2020; coastlines and inland waters: Smith and Wessel, 1 May 2015 AFGHANISTAN, YEAR 2019: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) COMPILED BY ACCORD, 29 JUNE 2020 Contents Conflict incidents by category Number of Number of reported fatalities 1 Number of Number of Category incidents with at incidents fatalities Number of reported incidents with at least one fatality 1 least one fatality Battles 9199 3908 26510 Conflict incidents by category 2 Explosions / Remote 4007 2179 14584 Development of conflict incidents from 2017 to 2019 2 violence Violence against civilians 405 179 388 Methodology 3 Strategic developments 242 56 189 Conflict incidents per province 4 Protests 59 3 5 Riots 3 1 4 Localization of conflict incidents 4 Total 13915 6326 41680 Disclaimer 9 This table is based on data from ACLED (datasets used: ACLED, 20 June 2020). Development of conflict incidents from 2017 to 2019 This graph is based on data from ACLED (datasets used: ACLED, 20 June 2020). 2 AFGHANISTAN, YEAR 2019: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) COMPILED BY ACCORD, 29 JUNE 2020 Methodology GADM. Incidents that could not be located are ignored. -

Afghanistan Opium Survey 2019

Islamic Republic of Afghanistan Afghanistan opium survey 2019 Socio-economic survey report: Drivers, causes and consequences of opium poppy cultivation Y 2021 FEBRUARY 2021 FEBRUAR FEBRUARY Page intentionally left blank Introduction The Afghanistan opium surveys 2019 collected and analysed detailed data on the location and extent of opium poppy cultivation, potential opium production and the socio-economic situation in rural areas. The results provide a detailed picture of the outcome of the 2019 opium season and, together with data from previous years, enable the identification of medium- and long-term trends in the evolution of illicit opium poppy cultivation in Afghanistan. This information is essential for planning, implementing and monitoring measures required for tackling a problem that has serious implications for Afghanistan and the international community. The survey was implemented by the Afghan government counterpart agency, the National Statistics and Information Authority (NSIA), in collaboration with UNODC. Since 2005, the Afghan counterpart and UNODC have also been involved in the verification of poppy eradication conducted by provincial governors and poppy-eradication forces. This information is essential for planning, implementing and monitoring counter-narcotic efforts. The opium survey is implemented within the technical framework of the UNODC Illicit Crop Monitoring Programme (ICMP). The objective of ICMP is to assist the international community in monitoring the extent and evolution of illicit crops in the context of the Plan of Action adopted by the 53rd session of the United Nations Commission on Narcotic Drugs in March 2009. Under ICMP, UNODC carries out monitoring activities in other countries affected by illicit crop cultivation in Asia (Myanmar), the Americas (Bolivia (Plurinational State of), Colombia, Ecuador, Mexico and Peru); and in Africa (Nigeria).