Part III Description of River Basins

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Case Study of Environmental Social Impact Assessment Methodology - Kajaki Hydropower Plant Project, Helmand, Afghanistan

Published by : International Journal of Engineering Research & Technology (IJERT) http://www.ijert.org ISSN: 2278-0181 Vol. 10 Issue 01, January-2021 A Case Study of Environmental Social Impact Assessment Methodology - Kajaki Hydropower Plant Project, Helmand, Afghanistan Hussain Etemadi Reza Khodadadi CEO, Omran Geotechnic Company, Environmental expert, Omran Geotechnic Company, Kabul, Afghanistan. Kabul, Afghanistan. Mohammad Amin Etemadi Marzia Hussaini Environmental expert, Omran Geotechnic Company, Social Expert, Afghanistan Ministry Of Foreign Affairs, Kabul, Afghanistan. Kabul, Afghanistan. Sathyanarayanan S Undergraduate, Govandi, Mumbai, India. Abstract— Construction activities in general have adverse additional 18.5 MW turbine was recently added to the existing effects on the surrounding environment. One of the efforts to powerhouse. Work on the planned service spillway radial keep the impact on the environment on check is Environmental gates, emergency spillway alternative, and raising the dam Social Impact Assessment (ESIA). The most convincing crest commenced during the late 1970s but construction definition of ESIA is a comprehensive document of a project’s activities ceased during the Soviet occupation and these potential environmental, social risks and impacts (IFC – 2012). This paper aims to delineate the process involved in assessing facilities were never completed. Consequently, the reservoir the impacts of one such construction, a construction of a has never been impounded to its design level of 1045 m. powerhouse in Kajaki Dam, Afghanistan. This powerhouse was constructed next to pre-existing powerhouse which comprises of The Kajaki Dam was built in the 1950s by the American three units. Along with the construction of a powerhouse an firm Morrison-Knudsen on contract with the then emergency spillway was also constructed and the penstock (4.9- Afghanistan’s Royal Government. -

Briefing Notes 17 July 2017

Group 22 - Information Centre Asylum and Migration Briefing Notes 17 July 2017 Afghanistan Armed confrontations The fighting, purges, and raids by the security forces continue as well as the ambushes and attacks of the insurgents and sometimes also civilians are killed or injured. According to media reports the following provinces were affected in the last two weeks: Lagham, Kunar, Nangarhar (east), Kunduz, Baghlan (northeast), Kandahar, Helmand, Zabul, Uruzgan (south), Ghazni (southeast), Faryab (north), and Parwan (centre). The renewed outbreak of fighting in Kunduz (northeast) drove more than 350 families from their homes. Reportedly Afghan government forces reconquered Nawa district in Helmand (south). Already on 04 July 2017 the leader of the Afghan branch of IS, Abu Sayed, is said to have died in an air strike on the regional IS headquarters in Kunar (east). Assaults and attacks On 11 July 2017 a high ranking criminal police officer was assassinated by the Taliban in Logar (centre). In Kandahar (south) two children died in the explosion of a roadside bomb. On 12 July 2017 the Taliban stopped a bus in Farah province (west) and shot at least seven of the 16 passengers. On 13 July 2017 tribal elders from Faryab province (north) complained that members of the Afghan Local Police (ALP) had shot eleven civilians and burnt down their houses in Dawlatabad district. On 14 July 2017 seven civilians, including women and children, were injured in an attack in Jalalabad (Nangarhar province, east). Furthermore two civilians were shot, one of them was a reputed poet. It is reported that several children died in an air strike on their school in Kunduz (northeast) on 15 July 2017. -

The ANSO Report (16-30 September 2010)

The Afghanistan NGO Safety Office Issue: 58 16-30 September 2010 ANSO and our donors accept no liability for the results of any activity conducted or omitted on the basis of this report. THE ANSO REPORT -Not for copy or sale- Inside this Issue COUNTRY SUMMARY Central Region 2-7 The impact of the elections and Zabul while Ghazni of civilian casualties are 7-9 Western Region upon CENTRAL was lim- and Kandahar remained counter-productive to Northern Region 10-15 ited. Security forces claim extremely volatile. With AOG aims. Rather it is a that this calm was the result major operations now un- testament to AOG opera- Southern Region 16-20 of effective preventative derway in various parts of tional capacity which al- Eastern Region 20-23 measures, though this is Kandahar, movements of lowed them to achieve a unlikely the full cause. An IDPs are now taking place, maximum of effect 24 ANSO Info Page AOG attributed NGO ‘catch originating from the dis- (particularly on perceptions and release’ abduction in Ka- tricts of Zhari and Ar- of insecurity) for a mini- bul resulted from a case of ghandab into Kandahar mum of risk. YOU NEED TO KNOW mistaken identity. City. The operations are In the WEST, Badghis was The pace of NGO incidents unlikely to translate into the most affected by the • NGO abductions country- lasting security as AOG wide in the NORTH continues onset of the elections cycle, with abductions reported seem to have already recording a three fold in- • Ongoing destabilization of from Faryab and Baghlan. -

In the Hari River Basin, with Re-Validation of P. Turcomana

Journal of Applied Biological Sciences 9 (3): 01-05, 2015 ISSN: 1307-1130, E-ISSN: 2146-0108, www.nobel.gen.tr Taxonomic Status of the Genus Paraschistura (Teleostei: Nemacheilidae) in the Hari River Basin, with Re-validation of P. turcomana Hamed MOUSAVI SABET1* Saber VATANDOUST2 Arash JOULADEH ROUDBAR3 Soheil EAGDERI4 1Department of Fisheries, Faculty of Natural Resources, University of Guilan, Sowmeh Sara, Guilan, Iran 2Department of Fisheries, Islamic Azad University, Babol Branch, Babol, Iran 3Department Fisheries, Sari University of Agriculture Sciences and Natural Resources, Mazandran, Iran 4Department of Fisheries, Faculty of Natural Resources, University of Tehran, Karaj, Iran *Corresponding author: Received: July 12, 2015 Email: [email protected] Accepted: August 23, 2015 Abstract The genus Paraschistura in the Hari River basin is reviewed, and diagnoses are presented for all the three recognized species. Paraschistura cristata and P. turcmenica are considered valid; and P. turcomana is revalidated. Paraschistura turcomana is a poorly known species from the Kushk River in the Murghab drainage at the border of Afghanistan and Turkmenistan, its validity has been questioned and a synonymy with P. turcmenica has been suggested. In this study, we compare P. turcmenica with the syntypes of P. turcomana. A comparison with the related taxa P. cristata and P. turcmenica reveals that P. turcomana can be separated from them by 7½ branched rays in dorsal fin, scaleless body, elongated and shallow body, shallow caudal peduncle, and colour pattern including obvious dark cross bars. The presence of two additional undescribed species is suggested from the basin. Keywords: Freshwater Fishes, Loach, Afghanistan, Iran, Turkmenistan. -

Table of Contents List of Abbreviations

وضعیت محیط زیست افغانستان فشارها، پیشرفت ها، چالشها و خﻻها The Environment of Afghanistan ( 2010 - 2017) Pressures, Progress, Challenges/Gaps Ghulam Mohammad Malikyar Dec. 2017 غﻻم محمد ملکیار حوت 1396 1 Table of Contents List of Abbreviations ................................................................................................................................................. 6 AFGHANISTAN'S MAJOR ENVIRONMENTAL ASSETS .................................................................................... 10 1. Introduction ................................................................................................................................................... 10 2. Physiography ................................................................................................................................................ 11 3. Population and Population growth ............................................................................................................... 12 4. General Education and Environmental Education ....................................................................................... 12 5. Socio-economic Process and Environment ................................................................................................... 13 6. Health and Sanitation ................................................................................................................................... 14 .[3] ........................................................................................................................................................................... -

Finally, I Am Grateful for the Continuous Support of My Parents,Siblings, Husband, Host Family, and Friends

Master Thesis in Peace and Conflict Studies Department of Peace and Conflict Studies Uppsala University "WE ARE FIGHTING A WATER WAR" The Character of the Upstream States and Post-TreatyTransboundary Water Conflict in Afghanistan and India MARYAM SAFI [email protected] Supervisor: Kristine Höglund Spring 2021 Map 1. Helmand River and Indus River (Source: the University of Nebraska Omaha, n.d.) 1 ABSTRACT Transboundary water treaties are often expected to prevent conflicts over waters from shared rivers. However, empirical evidence shows that some upstream countries continue to experience conflict after signing a water treaty. This study explains why some upstream countries experience high post-treaty transboundary water conflict levels while others do not. Departing from theories on the character of states, I argue that weaker upstream countries are more likely to experience post-treaty transboundary water conflict than stronger upstream states. This is because a weak upstream state has fewer capabilities, which creates an imbalance of power with its downstream riparian neighbor and presents a zero-sum game condition. As a result, the upstream state is more likely to experience a high level of conflict after signing an agreement. The hypothesis is tested on two transboundary river cases, the Helmand River Basin and the Indus River Basin, using a structured, focused comparison method. The data is collected through secondary sources, including books, journals, news articles, and reports, government records. The results of the study mainly support the theoretical arguments. It shows a significant relationship between the character of the upstream state and the level of post-treaty transboundary water conflictin the upstream state. -

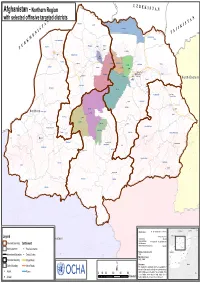

Download Map (PDF | 2.37

in te rn a tio n U a Z Khamyab l B Afghanistan - Northern Region E KIS T A N Qarqin with selected offinsive targeted districts A N Shortepa T N Kham Ab l a Qarqin n S o A i I t a n K T Shortepa r e t n S i JI I Kaldar N T A E Sharak Hairatan M Kaldar K Khani Chahar Bagh R Mardyan U Qurghan Mangajek Mangajik T Mardyan Dawlatabad Khwaja Du Koh Aqcha Aqcha Andkhoy Chahar Bolak Khwaja Du Koh Fayzabad Khulm Balkh Nahri Shahi Qaramqol Khaniqa Char Bolak Balkh Mazari Sharif Fayzabad Mazari Sharif Khulm Shibirghan Chimtal Dihdadi Nahri Shahi NorthNorth EasternEastern Dihdadi Marmul Shibirghan Marmul Dawlatabad Chimtal Char Kint Feroz Nakhchir Hazrati Sultan Hazrati Sultan Sholgara Chahar Kint Sholgara Sari Pul Aybak NorthernShirin Tagab Northern Sari Pul Aybak Qush Tepa Sayyad Sayyad Sozma Qala Kishindih Dara-I-Sufi Payin Khwaja Sabz Posh Sozma Qala Darzab Darzab Kishindih Khuram Wa Sarbagh Almar Dara-i-Suf Maymana Bilchiragh Sangcharak (Tukzar) Khuram Wa Sarbagh Sangcharak Zari Pashtun Kot Gosfandi Kohistanat (Pasni) Dara-I-Sufi Bala Gurziwan Ruyi Du Ab Qaysar Ruyi Du Ab Balkhab(Tarkhoj) Kohistanat Balkhab Kohistan Kyrgyzstan China Uzbekistan Tajikistan Map Doc Name: A1_lnd_eastern_admin_28112010 Legend CapitalCapital28 November 2010 Turkmenistan Jawzjan Badakhshan Creation Date: Kunduz Western WGS84 Takhar Western Balkh Projection/Datum: http://ochaonline.un.org/afghanistan Faryab Samangan Baghlan Provincial Boundary Settlement Web Resources: Sari Pul Nuristan Nominal Scale at A0 paper size: 1:640,908 Badghis Bamyan Parwan Kunar Kabul !! Maydan -

Afghanistan Agricultural Strategy

TC:TCP/AFG/4552 FINAL DRAFT TECHNICAL COOPERATION PROGRAMME PROMOTION OF AGRICULTURAL REHABILITATION AND DEVELOPMENT PROGRAMMES FOR AFGHANISTAN AFGHANISTAN AGRICULTURAL STRATEGY THE ISLAMIC REPUBLIC OF AFGHANISTAN prepared by FOOD AND AGRICULTURE ORGANIZATION OF THE UNITED NATIONS Rome January 1997 AFGHANISTAN VERSITY I NR II II I I II 111111 3 ACKU 00006806 3 TC:TCP/AFG/4552 FINAL DRAFT TECHNICAL COOPERATION PROGRAMME PROMOTION OF AGRICULTURAL REHABILITATION AND DEVELOPMENT PROGRAMMES FOR AFGHANISTAN AFGHANISTAN AGRICULTURAL STRATEGY THE ISLAMIC REPUBLIC OF AFGHANISTAN prepared by FOOD AND AGRICULTURE ORGANIZATION OF THE UNITED NATIONS Rome January 1997 Printed at: PanGraphics (Pvt) Ltd. Islamabad. CONTENTS Page FOREWORD 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 2 1. INTRODUCTION 5 1.1 Background 5 1.2 Assistance to Agriculture 6 1.3 Strategy Development 6 1.4 Constraints 8 1.5 Assumptions 9 1.6 Timing 10 1.7 Strategy Framework 11 2. THE STRATEGY 12 2.1 National Goal 12 2.2 Agricultural Sector Goal 12 2.3 Strategic Priorities 12 2.4 Development Profiles 16 2.4.1 Creating Food Security 16 2.4.2 Increasing Economic and Social Development 21 2.4.3 Raising Skills and Employment 25 2.4.4 Developing Natural Resource Management 29 3. ISSUES 32 3.1 Role of Government 32 3.2 Resource Utilisation 34 3.3 Creating Capacity 35 3.4 Credit 36 3.6 Sustainability 37 4. IMPLEMENTATION 38 4.1 Accurate Data 38 4.2 Delivering Services 38 4.3 Input Supply 39 4.4 Research 39 4.5 Extension and Training 40 4.6 Monitoring and Evaluation 40 4.7 Project Outlines 41 ANNEX 1. -

Social Water and Integrated Management Project Takhar Province, Afghanistan

Social Water and Integrated Management Project Takhar Province, Afghanistan Contract No. Food/2007/147-691 Reference: EuropeAid/125953/L/ACT/AF FINAL EVALUATION January 2011 Paul D Smith Natural Resources Consultant Contents ABBREVIATIONS, ACRONYMS AND LOCAL TERMS ...................................................................................................... 5 PROJECT DATA ............................................................................................................................................................ 6 SUMMARY OF EVALUATION ....................................................................................................................................... 6 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ................................................................................................................................................ 7 RELEVANCE AND QUALITY OF DESIGN ....................................................................................................................................... 7 EFFICIENCY OF IMPLEMENTATION ............................................................................................................................................ 7 EFFECTIVENESS .................................................................................................................................................................... 8 IMPACT PROSPECTS ............................................................................................................................................................. -

Selecting the Road to More and Better Jobspdf

SELECTING THE ROAD TO MORE AND BETTER JOBS SECTOR SELECTION REPORT OF THE ROAD TO JOBS PROJECT IN NORTHERN AFGHANISTAN AUGUST 2015 TABLE OF CONTENTS Background .......................................................................................................................................... 3 I. The sector selection process ............................................................................................................. 4 Participatory appraisals of competitive advantage (PACA) .......................................... 6 Rapid market assessments (RMAS) .............................................................................. 6 II. Sector selection criteria .................................................................................................................... 8 III. Analysis of findings and sector selection ..................................................................................... 10 IV. Conclusion and lessons ................................................................................................................ 14 Annex: technical notes, findings by sub-sector ................................................................................. 15 Cotton ............................................................................................................................ 15 Grapes/raisins ............................................................................................................... 24 Poultry .......................................................................................................................... -

Watershed Atlas Part IV

PART IV 99 DESCRIPTION PART IV OF WATERSHEDS I. MAP AND STATISTICS BY WATERSHED II. AMU DARYA RIVER BASIN III. NORTHERN RIVER BASIN IV. HARIROD-MURGHAB RIVER BASIN V. HILMAND RIVER BASIN VI. KABUL (INDUS) RIVER BASIN VII. NON-DRAINAGE AREAS PICTURE 84 Aerial view of Panjshir Valley in Spring 2003. Parwan, 25 March 2003 100 I. MAP AND STATISTICS BY WATERSHED Part IV of the Watershed Atlas describes the 41 watersheds Graphs 21-32 illustrate the main characteristics on area, popu- defined in Afghanistan, which includes five non-drainage areas lation and landcover of each watershed. Graph 21 shows that (Map 10 and 11). For each watershed, statistics on landcover the Upper Hilmand is the largest watershed in Afghanistan, are presented. These statistics were calculated based on the covering 46,882 sq. km, while the smallest watershed is the FAO 1990/93 landcover maps (Shapefiles), using Arc-View 3.2 Dasht-i Nawur, which covers 1,618 sq. km. Graph 22 shows that software. Graphs on monthly average river discharge curve the largest number of settlements is found in the Upper (long-term average and 1978) are also presented. The data Hilmand watershed. However, Graph 23 shows that the largest source for the hydrological graph is the Hydrological Year Books number of people is found in the Kabul, Sardih wa Ghazni, of the Government of Afghanistan – Ministry of Irrigation, Ghorband wa Panjshir (Shomali plain) and Balkhab watersheds. Water Resources and Environment (MIWRE). The data have Graph 24 shows that the highest population density by far is in been entered by Asian Development Bank and kindly made Kabul watershed, with 276 inhabitants/sq. -

Maah/Mrrd/Fao/Wfp National Crop Output Assessment

FAO FAAHM/AFGHANISTAN OSRO/AFG/111/USA MAAH/MRRD/FAO/WFP NATIONAL CROP OUTPUT ASSESSMENT 10th May to 5th June 2003 Farmer met in Badghis while weeding his rain-fed wheat field, 23 May 2003. Raphy Favre, FAO/FAIT Agronomist Consultant, Mission TL Anthony Fitzherbert, FAO Consultant Javier Escobedo, FAO Emergency Agronomist Consultant 25th July 2003 Kabul TABLE OF CONTENT I. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY II. INTRODUCTION III. METHODOLOGY 1. Estimation of Yield 1.1 Field Measurements for Yield Estimates 1.2 Crop Development Stage at the Time of the Assessment 1.3 Interviews with Farmers in the Field 1.4 Selection of Districts and Transects 1.5 Selection of Fields 2. Estimation of Land planted 3. Market Prices IV. RESULTS 4. Estimated Planted Area 4.1 Irrigated Land 4.2 Rain-fed Land 5. Estimated Wheat Yield 5.1 Irrigated Land 5.2 Rain-fed Land 6. Estimated Wheat Production 6.1 Irrigated Land 6.2 Rain-fed Land 6.3 Total Production 6.4 Agricultural Constraints in 2003 7. Estimated Barley Production at Regional Level 8. Wheat Grain Prices V. CONCLUSION & RECOMMENDATIONS ANNEXES ANNEX I - Changes of the Itinerary and Teams Composition due to Security Situation in Southern Afghanistan ANNEX II - Participants ANNEX III - Mission Itinerary and Districts covered by the Survey 2 TABLES Table 1: Estimated irrigated cultivated land in 2003; Total irrigated land cultivated In 2003, irrigated Wheat cultivated and irrigated Barley cultivated in 2003. Table 2: Estimated rain-fed cultivated land in 2003; Total rain-fed land cultivated in 2003, rain-fed Wheat cultivated and rain-fed Barley cultivated in 2003.