Power-Dressing at the Assyrian Court

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

December 16,1886

PORTLAND P !ESS I IAUU. Ill.l) JIM i»J, THURSDAY 1886. ISOB-VI^ 24._ PORTLAND, MORNING, DECEMBER 10, ffltKV/JfWffl PRICE THREE CENTS. OPIC1TAI, NOTICES. MMeBLLANlh. THE PORTLAND DAILY PRESS, FROM WASHINGTON. erous dangerous points, and finally madi MCQUADE CONVICTED. FOREICN. Published every day (Sundays excepted) by the this harbor. He was once beaten off by heac MAINE FOLK-LAND. old, had a place, a wife, and Immediate pros- PORTLAND PUBLISHING COMPANY, winds, but when the breeze changed h< pects of a larger family. Exchanoe Street, The Anti-Free Men Erv again attempted to affect an Although the .State has at no At 97 Portland, Me Ship Greatly extrance, ant The Great Trials Comes to a Mos t Cerir to be the Acres Held in Trust for Futuri > present pub- INSURANCE. this time succeeded. iny Beginning Watchful lic lands which It there are or OR. communications to with his cease may sell, eight E. Address all Weary B. at the Outlook. REED. couraged less watch and labor Conclusion. Towns. lie rau the schooner oi Satisfactory cf England’s Movements. MIX! TllOt'SAXD ACRES PORTLAND PUBLISHING CO. the flats and sought sleeo in his berth. Tbt which have and Botanic PRENTISS LORING’S AGENCY. vessel was found the not wholly passed to private Clairvoyant Physician The Bill Not by captain, who hat Story of the Celebrated 1 Likely to Be Considerec reached this Blnghan are have .N1EDICAI. BOOMS MAINE. city and dispatched a tug ir The Jury Agree on a Verdict In Four The r smoval of Chief Secret*..-/ ol parties. -

Retail Location List

RETAIL NURSERY AVAILABILITY LIST & Plant Locator: Updated 9/24/21 Here at Annie’s we grow thousands of different plant species right on site. We grow from seeds, cuttings and plugs and offer all plants in 4” containers. Plants available in our retail nursery will differ than those we offer online, and we generally have many more varieties available at retail. If a plant is listed here and not available online, it is not ready to ship or in some cases we are unable to ship certain plants. PLEASE NOTE: This list is updated every Friday and is the best source of information about what is in stock. However, some plants are only grown in small quantities and thus may sell quickly and not be available on the day you arrive at our nursery. The location codes indicate the section and row where the plant is located in the nursery. If you have questions or can’t find a plant, please don’t hesitate to ask one of our nursery staff. We are happy to help you find it. 9/24/2021 ww S ITEM NAME LOCATION Abutilon 'David's Red' 25-L Abutilon striatum "Redvein Indian Mallow" 21-E Abutilon 'Talini's Pink' 21-D Abutilon 'Victor Reiter' 24-H Acacia cognata 'Cousin Itt' 28-D Achillea millefolium 'Little Moonshine' 35-B ww S Aeonium arboreum 'Zwartkop' 3-E ww S Aeonium decorum 'Sunburst' 11-E ww S Aeonium 'Jack Catlin' 12-E ww S Aeonium nobile 12-E Agapanthus 'Elaine' 30-C Agapetes serpens 24-G ww S Agastache aurantiaca 'Coronado' 16-A ww S Agastache 'Black Adder' 16-A Agastache 'Blue Boa' 16-A ww S Agastache mexicana 'Sangria' 16-A Agastache rugosa 'Heronswood Mist' 14-A ww S Agave attenuata 'Ray of Light' 8-E ww S Agave bracteosa 3-E ww S Agave ovatifolia 'Vanzie' 7-E ww S Agave parryi var. -

The Developmentof Early Imperial Dress from the Tetrachs to The

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Birmingham Research Archive, E-theses Repository University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. The Development of Early Imperial Dress from the Tetrarchs to the Herakleian Dynasty General Introduction The emperor, as head of state, was the most important and powerful individual in the land; his official portraits and to a lesser extent those of the empress were depicted throughout the realm. His image occurred most frequently on small items issued by government officials such as coins, market weights, seals, imperial standards, medallions displayed beside new consuls, and even on the inkwells of public officials. As a sign of their loyalty, his portrait sometimes appeared on the patches sown on his supporters’ garments, embossed on their shields and armour or even embellishing their jewelry. Among more expensive forms of art, the emperor’s portrait appeared in illuminated manuscripts, mosaics, and wall paintings such as murals and donor portraits. Several types of statues bore his likeness, including those worshiped as part of the imperial cult, examples erected by public 1 officials, and individual or family groupings placed in buildings, gardens and even harbours at the emperor’s personal expense. -

How Do Cardinals Choose Which Hat to Wear?

How Do Cardinals Choose Which Hat to Wear? By Forrest Wickman March 12, 2013 6:30 PM A cardinal adjusts his mitre cap. Photo by Alessia Pierdomenico/Reuters One-hundred-fifteen Roman Catholic cardinals locked themselves up in the Vatican today to select the church’s next pope. In pictures of the cardinals, they were shown wearing a variety of unusual hats. How do cardinals choose their hats? To suit the occasion, to represent their homeland, or, sometimes, to make a personal statement. Cardinals primarily wear one of three different types. The most basic hat is a skullcap called the zucchetto (pl. zucchetti), which is a simple round hat that looks like a beanie or yarmulke. Next is the collapsible biretta, a taller, square-ridged cap with three peaks on top. There are certain times when it’s customary to put on the biretta, such as when entering and leaving church for Mass, but it’s often just personal preference. Cardinals wear both of these hats in red, which symbolizes how each cardinal should be willing to spill his blood for the church. (The zucchetto is actually worn beneath the biretta.) Some cardinals also wear regional variations on the hat, such as the Spanish style, which features four peaks instead of three. On special occasions, such as when preparing to elect the next leader of their church, they may also wear a mitre, which is a tall and usually white pointed hat. The mitre is the same style of cap commonly worn by the pope, and it comes in three different styles with varying degrees of ornamentation, according to the occasion. -

A Christian's Pocket Guide to the Papacy.Indd

1 WE HAVE A POPE! HABEMUS PAPAM! THE PAPAL OFFICE THROUGH HIS TITLES AND SYMBOLS ‘Gaudium Magnum: Habemus Papam!’ Th ese famous words introduce a new Pope to the world. Th ey are spoken to the throng that gathers in St. Peter’s Square to celebrate the occasion. Th e Pope is one of the last examples of absolute sovereignty in the modern world and embodies one of history’s oldest institutions. Th e executive, legislative, and juridical powers are all concentrated in the Papal offi ce. Until the Pope dies or resigns, he remains the Pope with all his titles and privileges. Th e only restriction on A CChristian'shristian's PPocketocket GGuideuide ttoo tthehe PPapacy.inddapacy.indd 1 22/9/2015/9/2015 33:55:42:55:42 PPMM 2 | A CHRISTIAN’S POCKET GUIDE TO THE PAPACY his power is that he cannot choose his own successor. In other words, the papacy is not dynastic. Th is task belongs to the College of electing Cardinals, that is, cardinals under eighty years old. Th ey gather to elect a new Pope in the ‘Conclave’ (from the Latin cum clave, i.e. locked up with a key), located in the Sistine Chapel. If the Pope cannot choose his own successor he can, nonetheless, choose those who elect. A good starting point for investigating the signifi cance of the Papacy is the 1994 Catechism of the Catholic Church. It is the most recent and comprehensive account of the Roman Catholic faith. Referring to the offi ce of the Pope, the Catechism notes in paragraph 882 that ‘the Roman Pontiff , by reason of his offi ce as Vicar of Christ, and as pastor of the entire Church has full, supreme, and universal power over the whole Church, a power which he can always exercise unhindered.’3 Th is brief sentence contains an apt summary of what the history and offi ce of the papacy are all about. -

1 © Australian Museum. This Material May Not Be Reproduced, Distributed

AMS564/002 – Scott sister’s second notebook, 1840-1862 © Australian Museum. This material may not be reproduced, distributed, transmitted, cached or otherwise used without permission from the Australian Museum. Text was transcribed by volunteers at the Biodiversity Volunteer Portal, a collaboration between the Australian Museum and the Atlas of Living Australia This is a formatted version of the transcript file from the second Scott Sisters’ notebook Page numbers in this document do not correspond to the notebook page numbers. The notebook was started from both ends at different times, so the transcript pages have been shuffled into approximately date order. Text in square brackets may indicate the following: - Misspellings, with the correct spelling in square brackets preceded by an asterisk rendersveu*[rendezvous] - Tags for types of content [newspaper cutting] - Spelled out abbreviations or short form words F[ield[. Nat[uralists] 1 AMS564/002 – Scott sister’s second notebook, 1840-1862 [Front cover] nulie(?) [start of page 130] [Scott Sisters’ page 169] Note Book No 2 Continued from first notebook No. 253. Larva (Noctua /Bombyx Festiva , Don n 2) found on the Crinum - 16 April 1840. Length 2 1/2 Incs. Ground color ^ very light blue, with numerous dark longitudinal stripes. 3 bright yellow bands, one on each side and one down the middle back - Head lightish red - a black velvet band, transverse, on the segment behind the front legs - but broken by the yellows This larva had a very offensive smell, and its habits were disgusting - living in the stem or in the thick part of the leaves near it, in considerable numbers, & surrounded by their accumulated filth - so that any touch of the Larva would soil the fingers.- It chiefly eat the thicker & juicier parts of the Crinum - On the 17 April made a very slight nest, underground, & some amongst the filth & leaves, by forming a cavity with agglutinated earth - This larva is showy - Drawing of exact size & appearance. -

St. John Vianney Catholic Community 401 Brassel Street Lockport, Illinois 60441 815-723-3291 Po Polsku 815-630-2745

St. John Vianney Catholic Community 401 Brassel Street Lockport, Illinois 60441 815-723-3291 www.sjvianneylockport.org Po Polsku 815-630-2745 Come Worship With Us In The Little Brown Church In The Fields Father Greg Podwysocki, Pastor Masses Confessions Tuesday - Friday 8:00 am Before Mass Saturday 8:00 am (Only on first Saturday) 4:15 pm Baptisms Call for appointment Sunday 7:00 am-Polish-Summer 9:30 am-English 11:30 am-Polish TODAY’S READINGS First Reading — Do not spend your life toil- ing for material gain (Ecclesiastes 1:2; 2:21- 23). Psalm — If today you hear his voice, harden not your hearts (Psalm 90). Second Reading — Christ has raised you to new life, so seek now what is above (Colossians 3:1-5, 9-11). Gospel — Be on guard against all greed, for your life does not consist of earthly posses- sions, but of the riches of the reign of God (Luke 12:13-21). The English translation of the Psalm Responses from Lectionary for Mass © 1969, 1981, 1997, Interna- tional Commission on English in the Liturgy Corporation. All rights reserved. Commission on English in the Liturgy Corporation. All rights reserved. 18th Sunday in Ordinary Time July 31, 2016 Confession Hours: LECTORS FOR NEXT WEEKEND: Saturday: 3:45 until 4:10pm Sat. 4:15 pm….Gwen Sun. 9:30 am….Mark Sunday: 9:10 until 9:25am 11:00 until 11:25am Think you might want to be a lector? Talk to Barb Dapriele 2nd Collection this weekend will be for Nuns Missions. Mass Intentions for the Week Saturday, July 30 at 4:15 p.m. -

The Crown Jewel of Divinity : Examining How a Coronation Crown Transforms the Virgin Into the Queen

Sotheby's Institute of Art Digital Commons @ SIA MA Theses Student Scholarship and Creative Work 2020 The Crown Jewel of Divinity : Examining how a coronation crown transforms the virgin into the queen Sara Sims Wilbanks Sotheby's Institute of Art Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.sia.edu/stu_theses Part of the Ancient, Medieval, Renaissance and Baroque Art and Architecture Commons Recommended Citation Wilbanks, Sara Sims, "The Crown Jewel of Divinity : Examining how a coronation crown transforms the virgin into the queen" (2020). MA Theses. 63. https://digitalcommons.sia.edu/stu_theses/63 This Thesis - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship and Creative Work at Digital Commons @ SIA. It has been accepted for inclusion in MA Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ SIA. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Crown Jewel of Divinity: Examining How A Coronation Crown Transforms The Virgin into The Queen By Sara Sims Wilbanks A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the Master’s Degree in Fine and Decorative Art & Design Sotheby’s Institute of Art 2020 12,572 words The Crown Jewel of Divinity: Examining How A Coronation Crown Transforms The Virgin into The Queen By: Sara Sims Wilbanks Inspired by Italian, religious images from the 15th and 16th centuries of the Coronation of the Virgin, this thesis will attempt to dissect the numerous depictions of crowns amongst the perspectives of formal analysis, iconography, and theology in order to deduce how this piece of jewelry impacts the religious status of the Virgin Mary. -

Clothing Terms from Around the World

Clothing terms from around the world A Afghan a blanket or shawl of coloured wool knitted or crocheted in strips or squares. Aglet or aiglet is the little plastic or metal cladding on the end of shoelaces that keeps the twine from unravelling. The word comes from the Latin word acus which means needle. In times past, aglets were usually made of metal though some were glass or stone. aiguillette aglet; specifically, a shoulder cord worn by designated military aides. A-line skirt a skirt with panels fitted at the waist and flaring out into a triangular shape. This skirt suits most body types. amice amice a liturgical vestment made of an oblong piece of cloth usually of white linen and worn about the neck and shoulders and partly under the alb. (By the way, if you do not know what an "alb" is, you can find it in this glossary...) alb a full-length white linen ecclesiastical vestment with long sleeves that is gathered at the waist with a cincture aloha shirt Hawaiian shirt angrakha a long robe with an asymmetrical opening in the chest area reaching down to the knees worn by males in India anklet a short sock reaching slightly above the ankle anorak parka anorak apron apron a garment of cloth, plastic, or leather tied around the waist and used to protect clothing or adorn a costume arctic a rubber overshoe reaching to the ankle or above armband a band usually worn around the upper part of a sleeve for identification or in mourning armlet a band, as of cloth or metal, worn around the upper arm armour defensive covering for the body, generally made of metal, used in combat. -

IV. the Chaplet, Or De Corona.380

0160-0220 – Tertullianus – De Corona The Chaplet, or De Corona this file has been downloaded from http://www.ccel.org/ccel/schaff/anf03.html ANF03. Latin Christianity: Its Founder, Tertullian Philip Schaff 93 IV. The Chaplet, or De Corona.380 ———————————— Chapter I. VERY lately it happened thus: while the bounty of our most excellent emperors381 was dispensed in the camp, the soldiers, laurel-crowned, were approaching. One of them, more a soldier of God, more stedfast than the rest of his brethren, who had imagined that they could serve two masters, his head alone uncovered, the useless crown in his hand—already even by that peculiarity known to every one as a Christian—was nobly conspicuous. Accordingly, all began to mark him out, jeering him at a distance, gnashing on him near at hand. The murmur is wafted to the tribune, when the person had just left the ranks. The tribune at once puts the question to him, Why are you so different in your attire? He declared that he had no liberty to wear the crown with the rest. Being urgently asked for his reasons, he answered, I am a Christian. O soldier! boasting thyself in God. Then the case was considered and voted on; the matter was remitted to a higher tribunal; the offender was conducted to the prefects. At once he put away the heavy cloak, his disburdening commenced; he loosed from his foot the military shoe, beginning to stand upon holy ground;382 he gave up the sword, which was not necessary either for the protection of our Lord; from his hand likewise dropped the laurel crown; and now, purple-clad with the hope of his own blood, shod with the preparation of the gospel, girt with the sharper word of God, completely equipped in the apostles’ armour, and crowned more worthily with the white crown of martyrdom, he awaits in prison the largess of Christ. -

A Dictionary of Men's Wear Works by Mr Baker

LIBRARY v A Dictionary of Men's Wear Works by Mr Baker A Dictionary of Men's Wear (This present book) Cloth $2.50, Half Morocco $3.50 A Dictionary of Engraving A handy manual for those who buy or print pictures and printing plates made by the modern processes. Small, handy volume, uncut, illustrated, decorated boards, 75c A Dictionary of Advertising In preparation A Dictionary of Men's Wear Embracing all the terms (so far as could be gathered) used in the men's wear trades expressiv of raw and =; finisht products and of various stages and items of production; selling terms; trade and popular slang and cant terms; and many other things curious, pertinent and impertinent; with an appendix con- taining sundry useful tables; the uniforms of "ancient and honorable" independent military companies of the U. S.; charts of correct dress, livery, and so forth. By William Henry Baker Author of "A Dictionary of Engraving" "A good dictionary is truly very interesting reading in spite of the man who declared that such an one changed the subject too often." —S William Beck CLEVELAND WILLIAM HENRY BAKER 1908 Copyright 1908 By William Henry Baker Cleveland O LIBRARY of CONGRESS Two Copies NOV 24 I SOB Copyright tntry _ OL^SS^tfU XXc, No. Press of The Britton Printing Co Cleveland tf- ?^ Dedication Conforming to custom this unconventional book is Dedicated to those most likely to be benefitted, i. e., to The 15000 or so Retail Clothiers The 15000 or so Custom Tailors The 1200 or so Clothing Manufacturers The 5000 or so Woolen and Cotton Mills The 22000 -

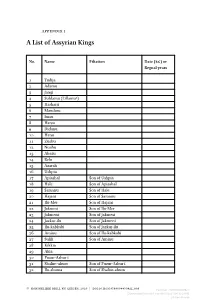

Downloaded from Brill.Com09/30/2021 04:32:21AM Via Free Access 198 Appendix I

Appendix I A List of Assyrian Kings No. Name Filiation Date (BC) or Regnal years 1 Tudija 2 Adamu 3 Jangi 4 Suhlamu (Lillamua) 5 Harharu 6 Mandaru 7 Imsu 8 Harsu 9 Didanu 10 Hanu 11 Zuabu 12 Nuabu 13 Abazu 14 Belu 15 Azarah 16 Ushpia 17 Apiashal Son of Ushpia 18 Hale Son of Apiashal 19 Samanu Son of Hale 20 Hajani Son of Samanu 21 Ilu-Mer Son of Hajani 22 Jakmesi Son of Ilu-Mer 23 Jakmeni Son of Jakmesi 24 Jazkur-ilu Son of Jakmeni 25 Ilu-kabkabi Son of Jazkur-ilu 26 Aminu Son of Ilu-kabkabi 27 Sulili Son of Aminu 28 Kikkia 29 Akia 30 Puzur-Ashur I 31 Shalim-ahum Son of Puzur-Ashur I 32 Ilu-shuma Son of Shalim-ahum © Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, 2020 | doi:10.1163/9789004430921_008 Fei Chen - 9789004430921 Downloaded from Brill.com09/30/2021 04:32:21AM via free access 198 Appendix I No. Name Filiation Date (BC) or Regnal years 33 Erishum I Son of Ilu-shuma 1974–1935 34 Ikunum Son of Erishum I 1934–1921 35 Sargon I Son of Ikunum 1920–1881 36 Puzur-Ashur II Son of Sargon I 1880–1873 37 Naram-Sin Son of Puzur-Ashur II 1872–1829/19 38 Erishum II Son of Naram-Sin 1828/18–1809b 39 Shamshi-Adad I Son of Ilu-kabkabic 1808–1776 40 Ishme-Dagan I Son of Shamshi-Adad I 40 yearsd 41 Ashur-dugul Son of Nobody 6 years 42 Ashur-apla-idi Son of Nobody 43 Nasir-Sin Son of Nobody No more than 44 Sin-namir Son of Nobody 1 year?e 45 Ibqi-Ishtar Son of Nobody 46 Adad-salulu Son of Nobody 47 Adasi Son of Nobody 48 Bel-bani Son of Adasi 10 years 49 Libaja Son of Bel-bani 17 years 50 Sharma-Adad I Son of Libaja 12 years 51 Iptar-Sin Son of Sharma-Adad I 12 years