1 the Ethics of Managing Elephants Prof. HPP (Hennie)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Plutarch on the Treatment of Animals: the Argument from Marginal Cases

Plutarch on the Treatment of Animals: The Argument 'from Marginal Cases Stephen T. Newmyer Duquesne University earlier philosophers in defense of animals are either ignored or summarily dismissed in most recent historical accounts of the growth of human concern for nonhuman species. In particular, this prejudice of contemporary moral philosophers has caused the sometimes profound arguments on the duties of human beings toward other species that appear in certain Greek writers to be largely overlooked.3 While it would be absurdly anachronistic to maintain that a philosophy of "animal rights" in a modem sense of that phrase can be traced to classical culture, a concern for the welfare of animals is clearly in evidence in some ancient writers In 1965, English novelist and essayist Brigid Brophy whose arguments in defense of animals at times reveal published an article in the London Sunday Times that striking foreshadowings of those developed in would exercise a profound influence on the crusade for contemporary philosophical inquiries into the moral better treatment of animals in Britain and the United status of animals. This study examines an anticipation, States. In this brief article, entitled simply "The Rights in the animal-related treatises of Plutarch, in particular ofAnimals," Brophy touched upon a number ofpoints in his De sollenia animalium (On the Cleverness of that were to become central to the arguments in defense Animals), of one of the more controversial arguments of animals formulated by subsequent representatives marshalled today in defense of animals, that which is of the animal rights movement.! Indeed, Richard D. commonly termed the argument from marginal cases.4 Ryder, one of the most prominent historians of the This argument maintains that it is wrong for humans to movement, judges Brophy's article to have been exploit animals in the belief that only humans are instrumental in inspiring the rebirth of interest in this capable of mtionality or feeling or perhaps the use of issue after decades, if not centuries, of neglect and language. -

All Creation Groans: the Lives of Factory Farm Animals in the United States

InSight: RIVIER ACADEMIC JOURNAL, VOLUME 13, NUMBER 1, SPRING 2017 “ALL CREATION GROANS”: The Lives of Factory Farm Animals in the United States Sr. Lucille C. Thibodeau, pm, Ph.D.* Writer-in-Residence, Department of English, Rivier University Today, more animals suffer at human hands than at any other time in history. It is therefore not surprising that an intense and controversial debate is taking place over the status of the 60+ billion animals raised and slaughtered for food worldwide every year. To keep up with the high demand for meat, industrialized nations employ modern processes generally referred to as “factory farming.” This article focuses on factory farming in the United States because the United States inaugurated this approach to farming, because factory farming is more highly sophisticated here than elsewhere, and because the government agency overseeing it, the Department of Agriculture (USDA), publishes abundant readily available statistics that reveal the astonishing scale of factory farming in this country.1 The debate over factory farming is often “complicated and contentious,”2 with the deepest point of contention arising over the nature, degree, and duration of suffering food animals undergo. “In their numbers and in the duration and depth of the cruelty inflicted upon them,” writes Allan Kornberg, M.D., former Executive Director of Farm Sanctuary in a 2012 Farm Sanctuary brochure, “factory-farm animals are the most widely abused and most suffering of all creatures on our planet.” Raising the specter of animal suffering inevitably raises the question of animal consciousness and sentience. Jeremy Bentham, the 18th-century founder of utilitarianism, focused on sentience as the source of animals’ entitlement to equal consideration of interests. -

Animal Rights Is a Social Justice Issue

WellBeing International WBI Studies Repository 2015 Animal Rights is a Social Justice Issue Robert C. Jones California State University, Chico, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://www.wellbeingintlstudiesrepository.org/anirmov Part of the Animal Studies Commons, Civic and Community Engagement Commons, and the Politics and Social Change Commons Recommended Citation Jones, R. C. (2015). Animal rights is a social justice issue. Contemporary Justice Review, 18(4), 467-482. This material is brought to you for free and open access by WellBeing International. It has been accepted for inclusion by an authorized administrator of the WBI Studies Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Animal Rights is a Social Justice Issue Robert C. Jones California State University – Chico KEYWORDS animal rights, animal liberation, animal ethics, sentience, social justice, factory farming, industrialized agriculture ABSTRACT The literature on social justice, and social justice movements themselves, routinely ignore nonhuman animals as legitimate subjects of social justice. Yet, as with other social justice movements, the contemporary animal liberation movement has as its focus the elimination of institutional and systemic domination and oppression. In this paper, I explicate the philosophical and theoretical foundations of the contemporary animal rights movement, and situate it within the framework of social justice. I argue that those committed to social justice – to minimizing violence, exploitation, domination, objectification, and oppression – are equally obligated to consider the interests of all sentient beings, not only those of human beings. Introduction I start this essay with a discouraging observation: despite the fact that the modern animal1 rights movement is now over 40 years old, the ubiquitous domination and oppression experienced by other- than-human animals has yet to gain robust inclusion in social justice theory or practice. -

An Inquiry Into Animal Rights Vegan Activists' Perception and Practice of Persuasion

An Inquiry into Animal Rights Vegan Activists’ Perception and Practice of Persuasion by Angela Gunther B.A., Simon Fraser University, 2006 Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in the School of Communication ! Angela Gunther 2012 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY Summer 2012 All rights reserved. However, in accordance with the Copyright Act of Canada, this work may be reproduced, without authorization, under the conditions for “Fair Dealing.” Therefore, limited reproduction of this work for the purposes of private study, research, criticism, review and news reporting is likely to be in accordance with the law, particularly if cited appropriately. Approval Name: Angela Gunther Degree: Master of Arts Title of Thesis: An Inquiry into Animal Rights Vegan Activists’ Perception and Practice of Persuasion Examining Committee: Chair: Kathi Cross Gary McCarron Senior Supervisor Associate Professor Robert Anderson Supervisor Professor Michael Kenny External Examiner Professor, Anthropology SFU Date Defended/Approved: June 28, 2012 ii Partial Copyright Licence iii Abstract This thesis interrogates the persuasive practices of Animal Rights Vegan Activists (ARVAs) in order to determine why and how ARVAs fail to convince people to become and stay veg*n, and what they might do to succeed. While ARVAs and ARVAism are the focus of this inquiry, the approaches, concepts and theories used are broadly applicable and therefore this investigation is potentially useful for any activist or group of activists wishing to interrogate and improve their persuasive practices. Keywords: Persuasion; Communication for Social Change; Animal Rights; Veg*nism; Activism iv Table of Contents Approval ............................................................................................................................. ii! Partial Copyright Licence ................................................................................................. -

Animals Liberation Philosophy and Policy Journal Volume 5, Issue 1

AAnniimmaallss LLiibbeerraattiioonn PPhhiilloossoopphhyy aanndd PPoolliiccyy JJoouurrnnaall VVoolluummee 55,, IIssssuuee 11 -- 22000077 Animal Liberation Philosophy and Policy Journal Volume 5, Issue 1 2007 Edited By: Steven Best, Chief Editor ____________________________________________________________ TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction Steven Best, Chief Editor Pg. 2-3 Introducing Critical Animal Studies Steven Best, Anthony J. Nocella II, Richard Kahn, Carol Gigliotti, and Lisa Kemmerer Pg. 4-5 Extrinsic and Intrinsic Arguments: Strategies for Promoting Animal Rights Katherine Perlo Pg. 6-19 Animal Rights Law: Fundamentalism versus Pragmatism David Sztybel Pg. 20-54 Unmasking the Animal Liberation Front Using Critical Pedagogy: Seeing the ALF for Who They Really Are Anthony J. Nocella II Pg. 55-64 The Animal Enterprise Terrorism Act: New, Improved, and ACLU-Approved Steven Best Pg. 65-81 BOOK REVIEWS _________________ In Defense of Animals: The Second Wave, by Peter Singer ed. (2005) Reviewed by Matthew Calarco Pg. 82-87 Dominion: The Power of Man, the Suffering of Animals, and the Call to Mercy, by Matthew Scully (2003) Reviewed by Lisa Kemmerer Pg. 88-91 Terrorists or Freedom Fighters?: Reflections on the Liberation of Animals, by Steven Best and Anthony J. Nocella, II, eds. (2004) Reviewed by Lauren E. Eastwood Pg. 92 Introduction Welcome to the sixth issue of our journal. You’ll first notice that our journal and site has undergone a name change. The Center on Animal Liberation Affairs is now the Institute for Critical Animal Studies, and the Animal Liberation Philosophy and Policy Journal is now the Journal for Critical Animal Studies. The name changes, decided through discussion among our board members, were prompted by both philosophical and pragmatic motivations. -

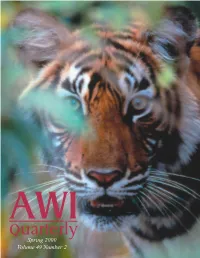

Quarterlyspring 2000 Volume 49 Number 2

AWI QuarterlySpring 2000 Volume 49 Number 2 ABOUT THE COVER For 25 years, the tiger (Panthera tigris) has been on Appendix I of the Conven- tion on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES), but an illegal trade in tiger skins and bones (which are used in traditional Chinese medicines) persists. Roughly 5,000 to 7,000 tigers have survived to the new millennium. Without heightened vigilance to stop habitat destruction, poaching and illegal commercialization of tiger parts in consuming countries across the globe, the tiger may be lost forever. Tiger Photos: Robin Hamilton/EIA AWI QuarterlySpring 2000 Volume 49 Number 2 CITES 2000 The Future of Wildlife In a New Millennium The Eleventh Meeting of the Conference of the Parties (COP 11) to the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) will take place in Nairobi, Kenya from April 10 – 20, 2000. Delegates from 150 nations will convene to decide the fate of myriad species across the globe, from American spotted turtles to Zimbabwean elephants. They will also examine ways in which the Treaty can best prevent overexploitation due to international trade by discussing issues such as the trade in bears, bushmeat, rhinos, seahorses and tigers. Adam M. Roberts and Ben White will represent the Animal Welfare Institute at the meeting and will work on a variety of issues of importance to the Institute and its members. Pages 8–13 of this issue of the AWI Quarterly, written by Adam M. Roberts (unless noted otherwise), outline our perspectives on a few of the vital issues for consideration at the CITES meeting. -

The African Elephant Under Threat

African Elephant Update Recent News from the WWF African Elephant Programme © WWF-Canon / Martin HARVEY Number 5 – June 2005 Cover photo: A herd of elephants on the move in Amboseli National Park, Kenya. The female in the middle of the herd has exceptionally long tusks. This edition of African Elephant Update was edited by PJ Stephenson. The content was compiled by PJ Stephenson & Alison Wilson. African Elephant Update (formerly Elephant Update) provides recent news on the conservation work funded by the WWF African Elephant Programme. It is aimed at WWF staff and WWF's partners such as range state governments, international and national non-governmental organizations, and donors. It is published at least once per year. Published in June 2005 by WWF - World Wide Fund for Nature (formerly World Wildlife Fund), CH- 1196, Gland, Switzerland Any reproduction in full or in part of this publication must mention the title and credit the above-mentioned publisher as the copyright owner. No photographs from this publication may be reproduced on the internet without prior authorization from WWF. The material and the geographical designations in this report do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of WWF concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. © text 2005 WWF All rights reserved In 2000 WWF launched a new African Elephant Programme. Building on 40 years of experience in elephant conservation, WWF’s new initiative aims to provide strategic field interventions to help guarantee a future for this threatened species. -

Legal Research Paper Series

Legal Research Paper Series NON HUMAN ANIMALS AND THE LAW: A BIBLIOGRAPHY OF ANIMAL LAW RESOURCES AT THE STANFORD LAW LIBRARY By Rita K. Lomio and J. Paul Lomio Research Paper No. 6 October 2005 Robert Crown Law Library Crown Quadrangle Stanford, California 94305-8612 NON HUMAN ANIMALS AND THE LAW: A BIBLIOGRPAHY OF ANIMAL LAW RESOURCES AT THE STANFORD LAW LIBRARY I. Books II. Reports III. Law Review Articles IV. Newspaper Articles (including legal newspapers) V. Sound Recordings and Films VI. Web Resources I. Books RESEARCH GUIDES AND BIBLIOGRAPHIES Hoffman, Piper, and the Harvard Student Animal Legal Defense Fund The Guide to Animal Law Resources Hollis, New Hampshire: Puritan Press, 1999 Reference KF 3841 G85 “As law students, we have found that although more resources are available and more people are involved that the case just a few years ago, locating the resource or the person we need in a particular situation remains difficult. The Guide to Animal Law Resources represents our attempt to collect in one place some of the resources a legal professional, law professor or law student might want and have a hard time finding.” Guide includes citations to organizations and internships, animal law court cases, a bibliography, law schools where animal law courses are taught, Internet resources, conferences and lawyers devoted to the cause. The International Institute for Animal Law A Bibliography of Animal Law Resources Chicago, Illinois: The International Institute for Animal Law, 2001 KF 3841 A1 B53 Kistler, John M. Animal Rights: A Subject Guide, Bibliography, and Internet Companion Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press, 2000 HV 4708 K57 Bibliography divided into six subject areas: Animal Rights: General Works, Animal Natures, Fatal Uses of Animals, Nonfatal Uses of Animals, Animal Populations, and Animal Speculations. -

Animal Rights Movement

Animal Rights Movement The Animal Protection Movement. Prevention of cruelty to animals became an important movement in early 19th Century England, where it grew alongside the humanitarian current that advanced human rights, including the anti-slavery movement and later the movement for woman suffrage. The first anti-cruelty bill, intended to stop bull-baiting, was introduced in Parliament in 1800. In 1822 Colonel Richard Martin succeeded in passing an act in the House of Commons preventing cruelty to such larger domestic animals as horses and cattle; two years later he organized the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (SPCA) to help enforce the law. Queen Victoria commanded the addition of the prefix "Royal" to the Society in 1840. Following the British model, Henry Bergh organized the American SPCA in New York in 1866 after returning from his post in St. Petersburg as secretary to the American legation in Russia; he hoped it would become national in scope, but the ASPCA remained primarily an animal shelter program for New York City. Other SPCAs and Humane Societies were founded in the U.S. beginning in the late 1860s (often with support from abolitionists) with groups in Pennsylvania, Massachusetts, and San Francisco among the first. Originally concerned with enforcing anti-cruelty laws, they soon began running animal shelters along the lines of a model developed in Philadelphia. The American Humane Association (AHA), with divisions for children and animals, was founded in 1877, and emerged as the leading national advocate for animal protection and child protection services. As the scientific approach to medicine expanded, opposition grew to the use of animals in medical laboratory research -- particularly in the era before anesthetics and pain-killers became widely available. -

Lasting Implications of the Elephants' Demise in Kenya and Tanzania

Lasting Implications of the Elephants’ Demise in Kenya and Tanzania Berlin Elgin Submitted to the graduate degree program in African and African American Studies, and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts. ________________________________ Chairperson: Dr. Peter Ojiambo ________________________________ Dr. Abel Chikanda ________________________________ Dr. Elizabeth MacGonagle Date Defended: May 8, 2017 The Thesis Committee for Berlin V. Elgin certifies that this is the approved version of the following thesis: Lasting Implications of the Elephants’ Demise in Kenya and Tanzania __________________________________ Chairperson: Dr. Peter Ojiambo Date Approved: May 12, 2017 ii Abstract The purpose of this study was to determine the effects of elephant deaths on the livelihoods of the people living in Kenya and Tanzania. The trade of ivory and conservation resistance were examined as the key factors for the death of an elephant. The study determined that poaching through the ivory trade, and elephants being killed in and around conservation parks because of conservation resistance, is detrimental to human livelihoods. The thesis recommends that the ivory trade must stop in order for elephant populations numbers in Kenya and Tanzania to positively affect the ecosystem and livelihoods, and conservation parks must be managed by local people. iii Table of Contents Chapter 1 Introduction 1 Conducting the Research 2 Gaps in the Literature and Research Limitations -

A Reading of Porphyry's on Abstinence From

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Justice Purity Piety: A Reading of Porphyry’s On Abstinence from Ensouled Beings A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Classics by Alexander Press 2020 © Copyright by Alexander Press 2020 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Justice Purity Piety: A Reading of Porphyry’s On Abstinence from Ensouled Beings by Alexander Press Doctor of Philosophy in Classics University of California, Los Angeles, 2020 Professor David Blank, Chair Abstract: Presenting a range of arguments against meat-eating, many strikingly familiar, Porphyry’s On Abstinence from Ensouled Beings (Greek Περὶ ἀποχῆς ἐµψύχων, Latin De abstinentia ab esu animalium) offers a sweeping view of the ancient debate concerning animals and their treatment. At the same time, because of its advocacy of an asceticism informed by its author’s Neoplatonism, Abstinence is often taken to be concerned primarily with the health of the human soul. By approaching Abstinence as a work of moral suasion and a work of literature, whose intra- and intertextual resonances yield something more than a collection of propositions or an invitation to Quellenforschung, I aim to push beyond interpretations that bracket the arguments regarding animals as merely dialectical; cast the text’s other-directed principle of justice as wholly ii subordinated to a self-directed principle of purity; or accept as decisive Porphyry’s exclusion of craftsmen, athletes, soldiers, sailors, and orators from his call to vegetarianism. -

Dog Meat Trade in South Korea: a Report on the Current State of the Trade and Efforts to Eliminate It

DOG MEAT TRADE IN SOUTH KOREA: A REPORT ON THE CURRENT STATE OF THE TRADE AND EFFORTS TO ELIMINATE IT By Claire Czajkowski* Within South Korea, the dog meat trade occupies a liminal legal space— neither explicitly condoned, nor technically prohibited. As a result of ex- isting in this legal gray area, all facets of the dog meat trade within South Korea—from dog farms, to transport, to slaughter, to consumption—are poorly regulated and often obfuscated from review. In the South Korean con- text, the dog meat trade itself not only terminally impacts millions of canine lives each year, but resonates in a larger national context: raising environ- mental concerns, and standing as a proxy for cultural and political change. Part II of this Article describes the nature of the dog meat trade as it oper- ates within South Korea; Part III examines how South Korean law relates to the dog meat trade; Part IV explores potentially fruitful challenges to the dog meat trade under South Korean law; similarly, Part V discusses grow- ing social pressure being deployed against the dog meat trade. I. INTRODUCTION ......................................... 30 II. STATE OF THE ISSUE ................................... 32 A. Scope of the Dog Meat Trade in South Korea ............ 32 B. Dog Farms ............................................ 33 C. Slaughter Methods .................................... 35 D. Markets and Restaurants .............................. 37 III. SOUTH KOREAN CULTURE AND LAWS ................. 38 A. Society and Culture ................................... 38 B. Current Laws ......................................... 40 1. Overview of Korean Law ............................ 40 a. Judicial System ................................ 41 b. Sources of Law ................................. 42 2. Animal Protection Act .............................. 42 a. Recently Passed Amendments .................... 45 b. Recently Proposed Amendments .................