Plutarch on the Treatment of Animals: the Argument from Marginal Cases

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Recommended publications

-

All Creation Groans: the Lives of Factory Farm Animals in the United States

InSight: RIVIER ACADEMIC JOURNAL, VOLUME 13, NUMBER 1, SPRING 2017 “ALL CREATION GROANS”: The Lives of Factory Farm Animals in the United States Sr. Lucille C. Thibodeau, pm, Ph.D.* Writer-in-Residence, Department of English, Rivier University Today, more animals suffer at human hands than at any other time in history. It is therefore not surprising that an intense and controversial debate is taking place over the status of the 60+ billion animals raised and slaughtered for food worldwide every year. To keep up with the high demand for meat, industrialized nations employ modern processes generally referred to as “factory farming.” This article focuses on factory farming in the United States because the United States inaugurated this approach to farming, because factory farming is more highly sophisticated here than elsewhere, and because the government agency overseeing it, the Department of Agriculture (USDA), publishes abundant readily available statistics that reveal the astonishing scale of factory farming in this country.1 The debate over factory farming is often “complicated and contentious,”2 with the deepest point of contention arising over the nature, degree, and duration of suffering food animals undergo. “In their numbers and in the duration and depth of the cruelty inflicted upon them,” writes Allan Kornberg, M.D., former Executive Director of Farm Sanctuary in a 2012 Farm Sanctuary brochure, “factory-farm animals are the most widely abused and most suffering of all creatures on our planet.” Raising the specter of animal suffering inevitably raises the question of animal consciousness and sentience. Jeremy Bentham, the 18th-century founder of utilitarianism, focused on sentience as the source of animals’ entitlement to equal consideration of interests. -

Animal Rights Is a Social Justice Issue

WellBeing International WBI Studies Repository 2015 Animal Rights is a Social Justice Issue Robert C. Jones California State University, Chico, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://www.wellbeingintlstudiesrepository.org/anirmov Part of the Animal Studies Commons, Civic and Community Engagement Commons, and the Politics and Social Change Commons Recommended Citation Jones, R. C. (2015). Animal rights is a social justice issue. Contemporary Justice Review, 18(4), 467-482. This material is brought to you for free and open access by WellBeing International. It has been accepted for inclusion by an authorized administrator of the WBI Studies Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Animal Rights is a Social Justice Issue Robert C. Jones California State University – Chico KEYWORDS animal rights, animal liberation, animal ethics, sentience, social justice, factory farming, industrialized agriculture ABSTRACT The literature on social justice, and social justice movements themselves, routinely ignore nonhuman animals as legitimate subjects of social justice. Yet, as with other social justice movements, the contemporary animal liberation movement has as its focus the elimination of institutional and systemic domination and oppression. In this paper, I explicate the philosophical and theoretical foundations of the contemporary animal rights movement, and situate it within the framework of social justice. I argue that those committed to social justice – to minimizing violence, exploitation, domination, objectification, and oppression – are equally obligated to consider the interests of all sentient beings, not only those of human beings. Introduction I start this essay with a discouraging observation: despite the fact that the modern animal1 rights movement is now over 40 years old, the ubiquitous domination and oppression experienced by other- than-human animals has yet to gain robust inclusion in social justice theory or practice. -

An Inquiry Into Animal Rights Vegan Activists' Perception and Practice of Persuasion

An Inquiry into Animal Rights Vegan Activists’ Perception and Practice of Persuasion by Angela Gunther B.A., Simon Fraser University, 2006 Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in the School of Communication ! Angela Gunther 2012 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY Summer 2012 All rights reserved. However, in accordance with the Copyright Act of Canada, this work may be reproduced, without authorization, under the conditions for “Fair Dealing.” Therefore, limited reproduction of this work for the purposes of private study, research, criticism, review and news reporting is likely to be in accordance with the law, particularly if cited appropriately. Approval Name: Angela Gunther Degree: Master of Arts Title of Thesis: An Inquiry into Animal Rights Vegan Activists’ Perception and Practice of Persuasion Examining Committee: Chair: Kathi Cross Gary McCarron Senior Supervisor Associate Professor Robert Anderson Supervisor Professor Michael Kenny External Examiner Professor, Anthropology SFU Date Defended/Approved: June 28, 2012 ii Partial Copyright Licence iii Abstract This thesis interrogates the persuasive practices of Animal Rights Vegan Activists (ARVAs) in order to determine why and how ARVAs fail to convince people to become and stay veg*n, and what they might do to succeed. While ARVAs and ARVAism are the focus of this inquiry, the approaches, concepts and theories used are broadly applicable and therefore this investigation is potentially useful for any activist or group of activists wishing to interrogate and improve their persuasive practices. Keywords: Persuasion; Communication for Social Change; Animal Rights; Veg*nism; Activism iv Table of Contents Approval ............................................................................................................................. ii! Partial Copyright Licence ................................................................................................. -

Animals Liberation Philosophy and Policy Journal Volume 5, Issue 1

AAnniimmaallss LLiibbeerraattiioonn PPhhiilloossoopphhyy aanndd PPoolliiccyy JJoouurrnnaall VVoolluummee 55,, IIssssuuee 11 -- 22000077 Animal Liberation Philosophy and Policy Journal Volume 5, Issue 1 2007 Edited By: Steven Best, Chief Editor ____________________________________________________________ TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction Steven Best, Chief Editor Pg. 2-3 Introducing Critical Animal Studies Steven Best, Anthony J. Nocella II, Richard Kahn, Carol Gigliotti, and Lisa Kemmerer Pg. 4-5 Extrinsic and Intrinsic Arguments: Strategies for Promoting Animal Rights Katherine Perlo Pg. 6-19 Animal Rights Law: Fundamentalism versus Pragmatism David Sztybel Pg. 20-54 Unmasking the Animal Liberation Front Using Critical Pedagogy: Seeing the ALF for Who They Really Are Anthony J. Nocella II Pg. 55-64 The Animal Enterprise Terrorism Act: New, Improved, and ACLU-Approved Steven Best Pg. 65-81 BOOK REVIEWS _________________ In Defense of Animals: The Second Wave, by Peter Singer ed. (2005) Reviewed by Matthew Calarco Pg. 82-87 Dominion: The Power of Man, the Suffering of Animals, and the Call to Mercy, by Matthew Scully (2003) Reviewed by Lisa Kemmerer Pg. 88-91 Terrorists or Freedom Fighters?: Reflections on the Liberation of Animals, by Steven Best and Anthony J. Nocella, II, eds. (2004) Reviewed by Lauren E. Eastwood Pg. 92 Introduction Welcome to the sixth issue of our journal. You’ll first notice that our journal and site has undergone a name change. The Center on Animal Liberation Affairs is now the Institute for Critical Animal Studies, and the Animal Liberation Philosophy and Policy Journal is now the Journal for Critical Animal Studies. The name changes, decided through discussion among our board members, were prompted by both philosophical and pragmatic motivations. -

Legal Research Paper Series

Legal Research Paper Series NON HUMAN ANIMALS AND THE LAW: A BIBLIOGRAPHY OF ANIMAL LAW RESOURCES AT THE STANFORD LAW LIBRARY By Rita K. Lomio and J. Paul Lomio Research Paper No. 6 October 2005 Robert Crown Law Library Crown Quadrangle Stanford, California 94305-8612 NON HUMAN ANIMALS AND THE LAW: A BIBLIOGRPAHY OF ANIMAL LAW RESOURCES AT THE STANFORD LAW LIBRARY I. Books II. Reports III. Law Review Articles IV. Newspaper Articles (including legal newspapers) V. Sound Recordings and Films VI. Web Resources I. Books RESEARCH GUIDES AND BIBLIOGRAPHIES Hoffman, Piper, and the Harvard Student Animal Legal Defense Fund The Guide to Animal Law Resources Hollis, New Hampshire: Puritan Press, 1999 Reference KF 3841 G85 “As law students, we have found that although more resources are available and more people are involved that the case just a few years ago, locating the resource or the person we need in a particular situation remains difficult. The Guide to Animal Law Resources represents our attempt to collect in one place some of the resources a legal professional, law professor or law student might want and have a hard time finding.” Guide includes citations to organizations and internships, animal law court cases, a bibliography, law schools where animal law courses are taught, Internet resources, conferences and lawyers devoted to the cause. The International Institute for Animal Law A Bibliography of Animal Law Resources Chicago, Illinois: The International Institute for Animal Law, 2001 KF 3841 A1 B53 Kistler, John M. Animal Rights: A Subject Guide, Bibliography, and Internet Companion Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press, 2000 HV 4708 K57 Bibliography divided into six subject areas: Animal Rights: General Works, Animal Natures, Fatal Uses of Animals, Nonfatal Uses of Animals, Animal Populations, and Animal Speculations. -

Animal Rights Movement

Animal Rights Movement The Animal Protection Movement. Prevention of cruelty to animals became an important movement in early 19th Century England, where it grew alongside the humanitarian current that advanced human rights, including the anti-slavery movement and later the movement for woman suffrage. The first anti-cruelty bill, intended to stop bull-baiting, was introduced in Parliament in 1800. In 1822 Colonel Richard Martin succeeded in passing an act in the House of Commons preventing cruelty to such larger domestic animals as horses and cattle; two years later he organized the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (SPCA) to help enforce the law. Queen Victoria commanded the addition of the prefix "Royal" to the Society in 1840. Following the British model, Henry Bergh organized the American SPCA in New York in 1866 after returning from his post in St. Petersburg as secretary to the American legation in Russia; he hoped it would become national in scope, but the ASPCA remained primarily an animal shelter program for New York City. Other SPCAs and Humane Societies were founded in the U.S. beginning in the late 1860s (often with support from abolitionists) with groups in Pennsylvania, Massachusetts, and San Francisco among the first. Originally concerned with enforcing anti-cruelty laws, they soon began running animal shelters along the lines of a model developed in Philadelphia. The American Humane Association (AHA), with divisions for children and animals, was founded in 1877, and emerged as the leading national advocate for animal protection and child protection services. As the scientific approach to medicine expanded, opposition grew to the use of animals in medical laboratory research -- particularly in the era before anesthetics and pain-killers became widely available. -

A Reading of Porphyry's on Abstinence From

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Justice Purity Piety: A Reading of Porphyry’s On Abstinence from Ensouled Beings A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Classics by Alexander Press 2020 © Copyright by Alexander Press 2020 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Justice Purity Piety: A Reading of Porphyry’s On Abstinence from Ensouled Beings by Alexander Press Doctor of Philosophy in Classics University of California, Los Angeles, 2020 Professor David Blank, Chair Abstract: Presenting a range of arguments against meat-eating, many strikingly familiar, Porphyry’s On Abstinence from Ensouled Beings (Greek Περὶ ἀποχῆς ἐµψύχων, Latin De abstinentia ab esu animalium) offers a sweeping view of the ancient debate concerning animals and their treatment. At the same time, because of its advocacy of an asceticism informed by its author’s Neoplatonism, Abstinence is often taken to be concerned primarily with the health of the human soul. By approaching Abstinence as a work of moral suasion and a work of literature, whose intra- and intertextual resonances yield something more than a collection of propositions or an invitation to Quellenforschung, I aim to push beyond interpretations that bracket the arguments regarding animals as merely dialectical; cast the text’s other-directed principle of justice as wholly ii subordinated to a self-directed principle of purity; or accept as decisive Porphyry’s exclusion of craftsmen, athletes, soldiers, sailors, and orators from his call to vegetarianism. -

Dog Meat Trade in South Korea: a Report on the Current State of the Trade and Efforts to Eliminate It

DOG MEAT TRADE IN SOUTH KOREA: A REPORT ON THE CURRENT STATE OF THE TRADE AND EFFORTS TO ELIMINATE IT By Claire Czajkowski* Within South Korea, the dog meat trade occupies a liminal legal space— neither explicitly condoned, nor technically prohibited. As a result of ex- isting in this legal gray area, all facets of the dog meat trade within South Korea—from dog farms, to transport, to slaughter, to consumption—are poorly regulated and often obfuscated from review. In the South Korean con- text, the dog meat trade itself not only terminally impacts millions of canine lives each year, but resonates in a larger national context: raising environ- mental concerns, and standing as a proxy for cultural and political change. Part II of this Article describes the nature of the dog meat trade as it oper- ates within South Korea; Part III examines how South Korean law relates to the dog meat trade; Part IV explores potentially fruitful challenges to the dog meat trade under South Korean law; similarly, Part V discusses grow- ing social pressure being deployed against the dog meat trade. I. INTRODUCTION ......................................... 30 II. STATE OF THE ISSUE ................................... 32 A. Scope of the Dog Meat Trade in South Korea ............ 32 B. Dog Farms ............................................ 33 C. Slaughter Methods .................................... 35 D. Markets and Restaurants .............................. 37 III. SOUTH KOREAN CULTURE AND LAWS ................. 38 A. Society and Culture ................................... 38 B. Current Laws ......................................... 40 1. Overview of Korean Law ............................ 40 a. Judicial System ................................ 41 b. Sources of Law ................................. 42 2. Animal Protection Act .............................. 42 a. Recently Passed Amendments .................... 45 b. Recently Proposed Amendments ................. -

In Defense of Animals: the Second Wave PDF Book

IN DEFENSE OF ANIMALS: THE SECOND WAVE PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Peter Singer | 264 pages | 02 Sep 2005 | John Wiley and Sons Ltd | 9781405119412 | English | Oxford, United Kingdom In Defense of Animals: The Second Wave PDF Book News IDA India. Goodreads helps you keep track of books you want to read. Enabling JavaScript in your browser will allow you to experience all the features of our site. In defense of animals is a collection of essays written by different authors, highlighting different aspects of compassion and animal defense. Utilitarianism and Animals: Gaverick Matheny. Learn how to enable JavaScript on your browser. Javascript is not enabled in your browser. I was very well versed in animal rights, I knew why I wasn't eating meat, and I remember this book not really adding anything I hadn't already wrestled with in my head. For a better shopping experience, please upgrade now. Jul 01, Nancy rated it really liked it Shelves: abuse , biology , business , ecology , favorites , horrible-events-inside , horror , nonfiction-biology. Related Searches. Travis Elise rated it liked it Jul 11, On the Question of Personhood beyond Homo sapiens. He is the author of Animal Liberation , first published in , and is widely credited with triggering the modern animal rights movement. The Bureau's plan is simply upping the ante on its decades-old…. Covering fractional order theory, simulation and experiments, this book explains how fractional order modelling and There are no discussion topics on this book yet. This section discussing real life issues involving our relationships with other animals comes after philosophical essays on the moral implications of our treatment of animals. -

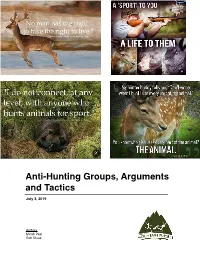

Anti-Hunting Groups, Arguments and Tactics, July 2019

Anti-Hunting Groups, Arguments and Tactics July 3, 2019 Authors Micah Peel Rob Shaul Anti-Hunting Groups, Arguments and Tactics Background: Hunting is declining as an outdoors activity in the United States, and overall the number of self-reported hunters is small part of the population. Hunter numbers in the United States dropped 15% from 2011 to 2016, according to a 2016 US Fish & Wildlife Service Report. In 2016, the report found 11.5 million hunters in the United States, of which 9.2 million are big game hunters. Big Game hunters are just 2.8% over the overall US Census estimated 2016 population of 323 million. Despite declining hunter numbers, and small percentage of the overall population which hunts, a 2017 Study found that strong majority of US Residents, 87%, agreed that it was acceptable to hunt for food. However, only 37% agreed that it was acceptable to hunt for a trophy. Recent successful predator anti-hunting campaigns, and widespread national condemnation of hunters who have killed trophy or exotic animals demonstrate that anti-hunting sentiment in the United States is increasing. As well, there was a 600% increase in people identifying as vegans in the U.S between 2014 and 2017. According to a report by research firm GlobalData, only 1% of U.S.consumers claimed to be vegan in 2014. And in 2017, that number rose to 6% - twice the number of big game hunters in the country. Vegans believe it’s unethical to eat animals, and opposed hunting for food. This study attempts to identify the most prominent and successful anti-hunting arguments, tactics and groups. -

Ag-Gag” Laws from Broad Spectrum of Interest Groups

STATEMENT OF OPPOSITION TO PROPOSED “AG-GAG” LAWS FROM BROAD SPECTRUM OF INTEREST GROUPS We, the undersigned group of civil liberties, public health, food safety, environmental, food justice, animal welfare, legal, workers’ rights, journalism, and First Amendment organizations and individuals, hereby state our opposition to proposed whistleblower suppression laws, known as “ag-gag” bills, being introduced in states around the country. These bills seek to criminalize investigations of farms that reveal critical information about the production of animal products. These bills represent a wholesale assault on many fundamental values shared by all people across the United States. Not only would these bills perpetuate animal abuse on industrial farms, they would also threaten workers’ rights, consumer health and safety, law enforcement investigations and the freedom of journalists, employees and the public at large to share information about something as fundamental as our food supply. We call on state legislators around the nation to drop or vote against these dangerous and un-American efforts. American Civil Liberties Union Center for Science in the Public Interest American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty Citizens Action Coalition of Indiana to Animals (ASPCA) Clean Water Network Amnesty International Compassion In World Farming Animal Legal Defense Fund Compassion Over Killing Animal Welfare Institute The Community Environmental Legal Defense Association of Prosecuting Attorneys Fund A Well-Fed World Consumer Federation of America -

IN DEFENSE of ANIMALS – Defending the Rights, Welfare and Habitats of Animals---Since 1983

EVEN NOW 10-28-08 HUMANE SOCIETY OF US (HSUS) Wayne Pacelle, President - Vote YES on California Proposition 2 Read New York Times “The Barnyard Strategist” by Maggie Jones ***** TEN PIGS RESCUED FROM MIDWEST FLOODS FIND PERMANENT REFUGE IN OREGON Scio, Oregon – October 24, 2008 – Farm Sanctuary, which operates the largest rescue and refuge network for farm animals in North America, transported 10 rescued pigs to Lighthouse Farm Sanctuary in Scio, Ore. last weekend. The animals were rescued in June and July off a levee in Oakville, Iowa, where they were stranded without food, clean water or shelter amidst floods that ravaged the Midwest this summer. The rescue, which resulted in the recovery of more than 60 young pigs and breeding sows left behind by evacuated farmers, was the most ambitious of Farm Sanctuary’s 22-year history of saving lives. Farm Sanctuary Brings Animals to New Home at Lighthouse Farm Sanctuary in Scio Farm Sanctuary works to end cruelty to farm animals and promotes compassionate living through rescue, education and advocacy. We envision a world where the violence that animal agriculture inflicts upon people, animals and the environment has ended, and where instead we exercise values of compassion. Get a Leg Up on Turkey Activism ***** IN DEFENSE OF ANIMALS – Defending the Rights, Welfare and Habitats of Animals---since 1983. Sign up to support IDA’s work and receive free e-newsletters In Defense of Animals is a registered 501(c)3 non-profit organization. In Defense of Animals, 3010 Kerner Blvd, San Rafael, California 94901 415 448 0048, [email protected] Meat: Making Global Warming Worse ***** FARM (Farm Animal Rights Movement) FARM (Farm Animal Rights Movement) is a tax-exempt national advocacy organization promoting plant-based (vegan) diets to save animals, reduce global warming, conserve environmental resources, and improve public health.