"Growth and Productivity of Vigorous 'Northern Spy'/MM.106 Apple Trees in Response to Annually Applied Growth Contr

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Apples Catalogue 2019

ADAMS PEARMAIN Herefordshire, England 1862 Oct 15 Nov Mar 14 Adams Pearmain is a an old-fashioned late dessert apple, one of the most popular varieties in Victorian England. It has an attractive 'pearmain' shape. This is a fairly dry apple - which is perhaps not regarded as a desirable attribute today. In spite of this it is actually a very enjoyable apple, with a rich aromatic flavour which in apple terms is usually described as Although it had 'shelf appeal' for the Victorian housewife, its autumnal colouring is probably too subdued to compete with the bright young things of the modern supermarket shelves. Perhaps this is part of its appeal; it recalls a bygone era where subtlety of flavour was appreciated - a lovely apple to savour in front of an open fire on a cold winter's day. Tree hardy. Does will in all soils, even clay. AERLIE RED FLESH (Hidden Rose, Mountain Rose) California 1930’s 19 20 20 Cook Oct 20 15 An amazing red fleshed apple, discovered in Aerlie, Oregon, which may be the best of all red fleshed varieties and indeed would be an outstandingly delicious apple no matter what color the flesh is. A choice seedling, Aerlie Red Flesh has a beautiful yellow skin with pale whitish dots, but it is inside that it excels. Deep rose red flesh, juicy, crisp, hard, sugary and richly flavored, ripening late (October) and keeping throughout the winter. The late Conrad Gemmer, an astute observer of apples with 500 varieties in his collection, rated Hidden Rose an outstanding variety of top quality. -

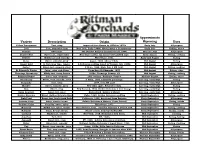

Variety Description Origin Approximate Ripening Uses

Approximate Variety Description Origin Ripening Uses Yellow Transparent Tart, crisp Imported from Russia by USDA in 1870s Early July All-purpose Lodi Tart, somewhat firm New York, Early 1900s. Montgomery x Transparent. Early July Baking, sauce Pristine Sweet-tart PRI (Purdue Rutgers Illinois) release, 1994. Mid-late July All-purpose Dandee Red Sweet-tart, semi-tender New Ohio variety. An improved PaulaRed type. Early August Eating, cooking Redfree Mildly tart and crunchy PRI release, 1981. Early-mid August Eating Sansa Sweet, crunchy, juicy Japan, 1988. Akane x Gala. Mid August Eating Ginger Gold G. Delicious type, tangier G Delicious seedling found in Virginia, late 1960s. Mid August All-purpose Zestar! Sweet-tart, crunchy, juicy U Minn, 1999. State Fair x MN 1691. Mid August Eating, cooking St Edmund's Pippin Juicy, crisp, rich flavor From Bury St Edmunds, 1870. Mid August Eating, cider Chenango Strawberry Mildly tart, berry flavors 1850s, Chenango County, NY Mid August Eating, cooking Summer Rambo Juicy, tart, aromatic 16th century, Rambure, France. Mid-late August Eating, sauce Honeycrisp Sweet, very crunchy, juicy U Minn, 1991. Unknown parentage. Late Aug.-early Sept. Eating Burgundy Tart, crisp 1974, from NY state Late Aug.-early Sept. All-purpose Blondee Sweet, crunchy, juicy New Ohio apple. Related to Gala. Late Aug.-early Sept. Eating Gala Sweet, crisp New Zealand, 1934. Golden Delicious x Cox Orange. Late Aug.-early Sept. Eating Swiss Gourmet Sweet-tart, juicy Switzerland. Golden x Idared. Late Aug.-early Sept. All-purpose Golden Supreme Sweet, Golden Delcious type Idaho, 1960. Golden Delicious seedling Early September Eating, cooking Pink Pearl Sweet-tart, bright pink flesh California, 1944, developed from Surprise Early September All-purpose Autumn Crisp Juicy, slow to brown Golden Delicious x Monroe. -

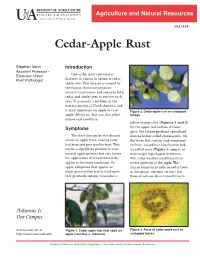

Cedar-Apple Rust

DIVISION OF AGRICULTURE RESEARCH & EXTENSION Agriculture and Natural Resources University of Arkansas System FSA7538 Cedar-Apple Rust Stephen Vann Introduction Assistant Professor One of the most spectacular Extension Urban Plant Pathologist diseases to appear in spring is cedar- apple rust. This disease is caused by the fungus Gymnosporangium juniperi-virginianae and requires both cedar and apple trees to survive each year. It is mainly a problem in the eastern portion of North America and is most important on apple or crab Figure 2. Cedar-apple rust on crabapple apple (Malus sp), but can also affect foliage. quince and hawthorn. yellow-orange color (Figures 1 and 2). Symptoms On the upper leaf surface of these spots, the fungus produces specialized The chief damage by this disease fruiting bodies called spermagonia. On occurs on apple trees, causing early the lower leaf surface (and sometimes leaf drop and poor quality fruit. This on fruit), raised hair-like fruiting bod can be a significant problem to com ies called aecia (Figure 3) appear as mercial apple growers but also harms microscopic cup-shaped structures. the appearance of ornamental crab Wet, rainy weather conditions favor apples in the home landscape. On severe infection of the apple. The apple, symptoms first appear as fungus forms large galls on cedar trees small green-yellow leaf or fruit spots in the spring (see next section), but that gradually enlarge to become a these structures do not greatly harm Arkansas Is Our Campus Visit our web site at: Figure 1. Cedar-apple rust (leaf spot) on Figure 3. Aecia of cedar-apple rust on https://www.uaex.uada.edu apple (courtesy J. -

Better Rootstocks for Apple Trees

Journal of the Department of Agriculture, Western Australia, Series 4 Volume 11 Number 12 1970 Article 3 1-1-1970 Better rootstocks for apple trees Frank Melville J. E. L. Cripps Follow this and additional works at: https://researchlibrary.agric.wa.gov.au/journal_agriculture4 Part of the Fruit Science Commons, Plant Breeding and Genetics Commons, and the Plant Pathology Commons Recommended Citation Melville, Frank and Cripps, J. E. L. (1970) "Better rootstocks for apple trees," Journal of the Department of Agriculture, Western Australia, Series 4: Vol. 11 : No. 12 , Article 3. Available at: https://researchlibrary.agric.wa.gov.au/journal_agriculture4/vol11/iss12/3 This article is brought to you for free and open access by Research Library. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of the Department of Agriculture, Western Australia, Series 4 by an authorized administrator of Research Library. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected], [email protected]. BETTER ROOTSTOCKS FOR APPLE TREES Mailing Merton rootstocks have given the best results in ten years' trials with apple rootstocks on Stoneville Research Station and on growers' properties. By F. MELVILLE, Assistant Chief, Horticulture Division and J. E. L. CRIPPS, Research Officer, Plant Research Division THE type of rootstock used imparts important characteristics to an apple tree. Tree size and stability, cropping characteristics, susceptibility to soil-borne pests and diseases and, to some extent, fruit quality are all affected by the choice of rootstock. To study these factors an apple rootstock Pomme de Neige experiment was planted at the Stoneville Pomme de Neige stock was originally Research Station in 1960. -

An Old Rose: the Apple

This is a republication of an article which first appeared in the March/April 2002 issue of Garden Compass Magazine New apple varieties never quite Rosaceae, the rose family, is vast, complex and downright confusing at times. completely overshadow the old ones because, as with roses, a variety is new only until the next This complexity has no better exemplar than the prince of the rose family, Malus, better known as the variety comes along and takes its apple. The apple is older in cultivation than the rose. It presents all the extremes in color, size, fragrance place. and plant character of its rose cousin plus an important added benefit—flavor! One can find apples to suit nearly every taste and cultural demand. Without any special care, apples grow where no roses dare. Hardy varieties like the Pippins, Pearmains, Snow, Lady and Northern Spy have been grown successfully in many different climates across the U.S. With 8,000-plus varieties worldwide and with new ones introduced annually, apple collectors in most climates are like kids in a candy store. New, Favorite and Powerhouse Apples New introductions such as Honeycrisp, Cameo and Pink Lady are adapted to a wide range of climates and are beginning to be planted in large quantities. The rich flavors of old favorites like Spitzenburg and Golden Russet Each one is a unique eating experience that are always a pleasant surprise for satisfies a modern taste—crunchy firmness, plenty inexperienced tasters. of sweetness and tantalizing flavor. Old and antique apples distinguish These new varieties show promise in the themselves with unusual skin competition for the #1 spot in the world’s colors and lingering aftertastes produce sections and farmers’ markets. -

FRUIT TREES COMMON HEIGHT SPREAD DESCRIPTION POLLINATOR ZONE NAME NOTE: Some Crabapples Can Be Used to Pollinate APPLE Some Apple Trees

FRUIT TREES COMMON HEIGHT SPREAD DESCRIPTION POLLINATOR ZONE NAME NOTE: Some crabapples can be used to pollinate APPLE some apple trees. Braeburn, Fuji, Gala, Golden Delicious, Honey Crisp, Large red apple, sweet and tart, white flesh. Good for eating, Cortland 5m 4m Jonamac, McIntosh, Red Delicious, Spartan. Most 4 cooking and cider. Late September white-blossom crabapples will also pollinate. Cortland, Jazz, Granny Smith, Ida Red, McIntosh, Hazen Dark red, medium firm, juicy. Good for eating, desert, 5m 4m Paula Red, Spartan, Winecrisp. Most white- 4 (semi-dwarf) cooking. Late August. blossom crabapples will also pollinate. Cortland, Empire, Fuji, Golden Russet, Granny Smith, Honeycrisp, Jonathan, McIntosh, Red Very large green-yellow fruit. Good for eating, cooking, Delicious, Winecrisp. Most white-blossom Mutsu (Crispin) 6m 4m 5 baking. Mid-October. crabapples and Dolgo Crabapple will also pollinate. NOTE: Mutsu is a tri-pollinator that requires two other varieties to produce fruit. Braeburn, Fuji, Golden Delicious, Honeycrisp, Large red apple, tart, firm flesh. Old-time favourite desert and Northern Spy 5m 4m Jonamac. Most white-blossom crabapples will also 4 baking apple. Mid-October. pollinate. Braeburn, Cortland, Gala, Golden Delicious, Granny Large red apple. Crisp skin with soft, sweet flesh. Good Smith, Honeycrisp, Jazz, Jonathan, Northern Spy, Red Delicious 5m 4m 5 eating and desert apple. Great pollinizer. Late September. Spartan, Winecrisp. Most white-blossom crabapples will also pollinate. Braeburn, Cortland, Fuji, Gala, Golden Delicious, Granny Smith, Honey Crisp, Red Delicious, Medium size, dark red, McIntosh type with juicy, sweet flesh. Winecrisp. Most white-blossom crabapples and Spartan 5m 4m 5 Fresh eating & baking. -

INF03 Reduce Lists of Apple Varieites

ECE/TRADE/C/WP.7/GE.1/2009/INF.3 Specialized Section on Standardization of Fresh Fruit and Vegetables Fifty-fifth session Geneva, 4 - 8 May 2009 Items 4(a) of the provisional agenda REVISION OF UNECE STANDARDS Proposals on the list of apple varieties This note has been put together by the secretariat following the decision taken by the Specialized Section at its fifty-fourth session to collect information from countries on varieties that are important in international trade. Replies have been received from the following countries: Canada, Czech Republic, Finland, France, Germany, Italy, Netherlands, New Zealand, Poland, Slovakia, South Africa, Sweden, Switzerland and the USA. This note also includes the documents compiled for the same purpose and submitted to the fifty-second session of the Specialized Section. I. Documents submitted to the 52nd session of the Specialized Section A. UNECE Standard for Apples – List of Varieties At the last meeting the 51 st session of the Specialized Section GE.1 the delegation of the United Kingdom offered to coordinate efforts to simplify the list of apple varieties. The aim was to see what the result would be if we only include the most important varieties that are produced and traded. The list is designed to help distinguish apple varieties by colour groups, size and russeting it is not exhaustive, non-listed varieties can still be marketed. The idea should not be to list every variety grown in every country. The UK asked for views on what were considered to be the most important top thirty varieties. Eight countries sent their views, Italy, Spain, the Netherlands, USA, Slovakia, Germany Finland and the Czech Republic. -

The Decline of the Apple

The Decline of the Apple The development of the apple in this century has been partial- ly a retrogression. Its breeding program has been geared almost completely to the commercial interests. The criteria for selection of new varieties have been an apple that will keep well under refrigeration, an apple that will ship without bruising, an apple of a luscious color that will attract the housewife to buy it from the supermarket bins. That the taste of this selected apple is in- ferior has been ignored. As a result, sharpness of flavor and variety of flavor are disappearing. The apple is becoming as standardized to mediocrity as the average manufactured prod- uct. And as small farms with their own orchards dwindle and the average person is forced to eat only apples bought from commercial growers, the coming generations will scarcely know how a good apple tastes. This is not to say that all of the old varieties were good. Many of them were as inferior as a Rome Beauty or a Stark’s Delicious. But the best ones were of an excellence that has almost dis- appeared. As a standard of excellence by which to judge, I would set the Northern Spy as the best apple ever grown in the United States. To bite into the tender flesh of a well-ripened Spy and have its juice ooze around the teeth and its rich tart flavor fill the mouth and its aroma rise up into the nostrils is one of the outstanding experiences of all fruit eating. More than this, the Spy is just as good when cooked as when eaten raw. -

Apple Pollination Groups

Flowering times of apples RHS Pollination Groups To ensure good pollination and therefore a good crop, it is essential to grow two or more different cultivars from the same Flowering Group or adjacent Flowering Groups. Some cultivars are triploid – they have sterile pollen and need two other cultivars for good pollination; therefore, always grow at least two other non- triploid cultivars with each one. Key AGM = RHS Award of Garden Merit * Incompatible with each other ** Incompatible with each other *** ‘Golden Delicious’ may be ineffective on ‘Crispin’ (syn. ‘Mutsu’) Flowering Group 1 Very early; pollinated by groups 1 & 2 ‘Gravenstein’ (triploid) ‘Lord Suffield’ ‘Manks Codlin’ ‘Red Astrachan’ ‘Stark Earliest’ (syn. ‘Scarlet Pimpernel’) ‘Vista Bella’ Flowering Group 2 Pollinated by groups 1,2 & 3 ‘Adams's Pearmain’ ‘Alkmene’ AGM (syn. ‘Early Windsor’) ‘Baker's Delicious’ ‘Beauty of Bath’ (partial tip bearer) ‘Beauty of Blackmoor’ ‘Ben's Red’ ‘Bismarck’ ‘Bolero’ (syn. ‘Tuscan’) ‘Cheddar Cross’ ‘Christmas Pearmain’ ‘Devonshire Quarrenden’ ‘Egremont Russet’ AGM ‘George Cave’ (tip bearer) ‘George Neal’ AGM ‘Golden Spire’ ‘Idared’ AGM ‘Irish Peach’ (tip bearer) ‘Kerry Pippin’ ‘Keswick Codling’ ‘Laxton's Early Crimson’ ‘Lord Lambourne’ AGM (partial tip bearer) ‘Maidstone Favourite’ ‘Margil’ ‘Mclntosh’ ‘Red Melba’ ‘Merton Charm’ ‘Michaelmas Red’ ‘Norfolk Beauty’ ‘Owen Thomas’ ‘Reverend W. Wilks’ ‘Ribston Pippin’ AGM (triploid, partial tip bearer) ‘Ross Nonpareil’ ‘Saint Edmund's Pippin’ AGM (partial tip bearer) ‘Striped Beefing’ ‘Warner's King’ AGM (triploid) ‘Washington’ (triploid) ‘White Transparent’ Flowering Group 3 Pollinated by groups 2, 3 & 4 ‘Acme’ ‘Alexander’ (syn. ‘Emperor Alexander’) ‘Allington Pippin’ ‘Arthur Turner’ AGM ‘Barnack Orange’ ‘Baumann's Reinette’ ‘Belle de Boskoop’ AGM (triploid) ‘Belle de Pontoise’ ‘Blenheim Orange’ AGM (triploid, partial tip bearer) ‘Bountiful’ ‘Bowden's Seedling’ ‘Bramley's Seedling’ AGM (triploid, partial tip bearer) ‘Brownlees Russett’ ‘Charles Ross’ AGM ‘Cox's Orange Pippin’ */** ‘Crispin’ (syn. -

Growing Apples for Craft Ciders Ian A

Growing Apples for Craft Ciders Ian A. Merwin Professor of Horticulture Emeritus—Cornell University Grower and Cider-maker—Black Diamond Farm ider has been a mainstay food and fermented bever- ies”) around the country are now seeking apple varieties known age for thousands of years. Domesticated apples were for making top quality ciders. The demand for these varieties brought to America by the first European colonists, and greatly exceeds their current supply, because only a few of the C from 1640 to 1840 new cideries have productive orchards or expertise in growing “There is significant growing interest in most of our or- apples. The un-met demand for special cider apples has led chards consisted growers across the US and Canada to consider these apples as hard cider with the number of cideries of seedling apples, an alternative to growing mainstream varieties, because the best- in NY State reaching 53. In this article grown primar- known cider apples fetch prices as high as $400 per 20-bushel I summarize our 30 years of experience ily for sweet and bin. My purpose in writing this article is to summarize what I at Cornell and on my own farm of hard (fermented) have learned about growing these cider apples over the past 30 growing hard cider varieties.” cider. Despite years, and to make this information available to those interested this long history, in cider and cider apples. hard cider was not considered A Note of Caution an economically important drink in the US until quite recently, Modern orchards cost about $25,000 per acre to establish and when the USDA and several apple-growing states began to col- bring them into commercial production. -

2014 Ciderdays Salon Tasting Guide

2014 CiderDays Salon Tasting Guide Tasting notes compiled by Ben Watson, author of Cider, Hard & Sweet: History, Traditions and Making Your Own More information on CiderDays at www.ciderdays.org 2014 Cider Salon Featured Ciders Asterisk * indicates producers who are planning to attend CiderDays (N) indicates producers who are new to the Cider Salon this year Aaron Burr Cidery * Table 1 2251 Route 209, Wurtsboro, NY 12790; 845-468-5867; www.aaronburrcider.com Homestead Perry Made from wild foraged pears. Bottle fermented and disgorged. The aroma is meaty and yeasty, but it tastes nothing like its nose. It’s balanced, delicate and off-dry; 8.1% abv. Isle Au Haut, Homestead Cider Made from uncultivated apples growing along the coast of Isle Au Haut, Maine. Naturally fermented (on island), the fragrant nose keeps a lot of the apple. Dry and still, the sharp body is viscous and colorful with notes of butterscotch. AEppel Treow Winery & Distillery Table 1 Brightonwoods Orchard, 1072 288th Avenue, Burlington, WI 53105; www.appletrue.com, distributed by Shelton Brothers, Belchertown, MA; www. sheltonbrothers.com Perry Charles McGonegal uses a blend of Bosc and Comice dessert pears in the traditional champagne method to produce this semi-sweet spar- residual sugar. kling pear wine. Floral bouquet; complex, creamy finish. 7.5% abv.; 5% Orchard Oriole Perry Made exclusively from a blend of traditional English perry pears grown at Brightonwoods Orchard. Varieties include Brandy, Thorn, Taynton Squash, Winnals Longdon, Barland, Barnet, and Normanschein Cidre- birne. This perry is light, dry, and complex, tart and musky, and quite tannic. Very soft carbonation. -

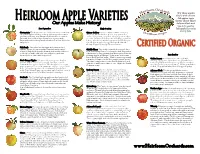

Heirloom Apple Varieties Better Sliced

om Orc eirlo hard H s Tr y these apples sliced with cheese. All apples taste Heirloom Apple Varieties better sliced. More delicate flesh and Our Apples Make History! less skin assures Late September Early October full apple flavor in every bite. Gravenstein: The Gravenstein is considered to be one of the best Grimes Golden: If you are a Golden Delicious fan, try Ho on all-around apples for baking, cooking and eating. it has a sweet, the parent, Grimes Golden. A clear, deep yellow skin od River, Oreg tart flavor and juicy, crisp texture. the Gravenstein is native to covers a fine grained, spicy flesh. Very juicy and excellent Denmark, discovered in 1699. It traveled to America with for cider. Its tender flesh keeps it from holding up well for Russian fur traders, who planted orchards at Fort Ross, CA in the baking. The Grimes Golden’s exceptional flavor keeps it a early 1800's. favorite dessert apple of many. Discovered in Brook County, Virginia in 1804 by Thomas Grimes. Pink Pearl: Cut or bite into this apple and you are in for a Certified Organic surprise. In fact, it is an offspring of another variety called Calville Blanc: This world renowned dessert apple dates 'Surprise'! Pink fleshed, pearly skinned, good tasting with sweet from 16th century France. Its’ flattened round shape makes to tart flavor. Makes pink applesauce and pretty fruit tarts. it distinctive looking, so much that Monet put it in his 1879 Aromatic flavor with a hint of grapefruit. painting “Apples and Grapes”. It has a tart, effervescent Late October flavor, and is good for eating.