B What Is Digital Photography?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Xerox Confidentcolor Technology Putting Exacting Control in Your Hands

Xerox FreeFlow® The future-thinking Print Server ConfidentColor Technology print server. Brochure It anticipates your needs. With the FreeFlow Print Server, you’re positioned to not only better meet your customers’ demands today, but to accommodate whatever applications you need to print tomorrow. Add promotional messages to transactional documents. Consolidate your data center and print shop. Expand your color-critical applications. Move files around the world. It’s an investment that allows you to evolve and grow. PDF/X support for graphic arts Color management for applications. transactional applications. With one button, the FreeFlow Print Server If you’re a transactional printer, this is the assures that a PDF/X file runs as intended. So print server for you. It supports color profiles when a customer embeds color-management in an IPDS data stream with AFP Color settings in a file using Adobe® publishing Management—so you can print color with applications, you can run that file with less time confidence. Images and other content can be in prepress and with consistent color. Files can incorporated from a variety of sources and reliably be sent to multiple locations and multiple appropriately rendered for accurate results. And printers with predictable results. when you’re ready to expand into TransPromo applications, it’s ready, too. Xerox ConfidentColor Technology Find out more Putting exacting control To learn more about the FreeFlow Print Server and ConfidentColor Technology, contact your Xerox sales representative or call 1-800-ASK-XEROX. Or visit us online at www.xerox.com/freeflow. in your hands. © 2009 Xerox Corporation. All rights reserved. -

Digital Holography Using a Laser Pointer and Consumer Digital Camera Report Date: June 22Nd, 2004

Digital Holography using a Laser Pointer and Consumer Digital Camera Report date: June 22nd, 2004 by David Garber, M.E. undergraduate, Johns Hopkins University, [email protected] Available online at http://pegasus.me.jhu.edu/~lefd/shc/LPholo/lphindex.htm Acknowledgements Faculty sponsor: Prof. Joseph Katz, [email protected] Project idea and direction: Dr. Edwin Malkiel, [email protected] Digital holography reconstruction: Jian Sheng, [email protected] Abstract The point of this project was to examine the feasibility of low-cost holography. Can viable holograms be recorded using an ordinary diode laser pointer and a consumer digital camera? How much does it cost? What are the major difficulties? I set up an in-line holographic system and recorded both still images and movies using a $600 Fujifilm Finepix S602Z digital camera and a $10 laser pointer by Lazerpro. Reconstruction of the stills shows clearly that successful holograms can be created with a low-cost optical setup. The movies did not reconstruct, due to compression and very low image resolution. Garber 2 Theoretical Background What is a hologram? The Merriam-Webster dictionary defines a hologram as, “a three-dimensional image reproduced from a pattern of interference produced by a split coherent beam of radiation (as a laser).” Holograms can produce a three-dimensional image, but it is more helpful for our purposes to think of a hologram as a photograph that can be refocused at any depth. So while a photograph taken of two people standing far apart would have one in focus and one blurry, a hologram taken of the same scene could be reconstructed to bring either person into focus. -

What Resolution Should Your Images Be?

What Resolution Should Your Images Be? The best way to determine the optimum resolution is to think about the final use of your images. For publication you’ll need the highest resolution, for desktop printing lower, and for web or classroom use, lower still. The following table is a general guide; detailed explanations follow. Use Pixel Size Resolution Preferred Approx. File File Format Size Projected in class About 1024 pixels wide 102 DPI JPEG 300–600 K for a horizontal image; or 768 pixels high for a vertical one Web site About 400–600 pixels 72 DPI JPEG 20–200 K wide for a large image; 100–200 for a thumbnail image Printed in a book Multiply intended print 300 DPI EPS or TIFF 6–10 MB or art magazine size by resolution; e.g. an image to be printed as 6” W x 4” H would be 1800 x 1200 pixels. Printed on a Multiply intended print 200 DPI EPS or TIFF 2-3 MB laserwriter size by resolution; e.g. an image to be printed as 6” W x 4” H would be 1200 x 800 pixels. Digital Camera Photos Digital cameras have a range of preset resolutions which vary from camera to camera. Designation Resolution Max. Image size at Printable size on 300 DPI a color printer 4 Megapixels 2272 x 1704 pixels 7.5” x 5.7” 12” x 9” 3 Megapixels 2048 x 1536 pixels 6.8” x 5” 11” x 8.5” 2 Megapixels 1600 x 1200 pixels 5.3” x 4” 6” x 4” 1 Megapixel 1024 x 768 pixels 3.5” x 2.5” 5” x 3 If you can, you generally want to shoot larger than you need, then sharpen the image and reduce its size in Photoshop. -

Sample Manuscript Showing Specifications and Style

Information capacity: a measure of potential image quality of a digital camera Frédéric Cao 1, Frédéric Guichard, Hervé Hornung DxO Labs, 3 rue Nationale, 92100 Boulogne Billancourt, FRANCE ABSTRACT The aim of the paper is to define an objective measurement for evaluating the performance of a digital camera. The challenge is to mix different flaws involving geometry (as distortion or lateral chromatic aberrations), light (as luminance and color shading), or statistical phenomena (as noise). We introduce the concept of information capacity that accounts for all the main defects than can be observed in digital images, and that can be due either to the optics or to the sensor. The information capacity describes the potential of the camera to produce good images. In particular, digital processing can correct some flaws (like distortion). Our definition of information takes possible correction into account and the fact that processing can neither retrieve lost information nor create some. This paper extends some of our previous work where the information capacity was only defined for RAW sensors. The concept is extended for cameras with optical defects as distortion, lateral and longitudinal chromatic aberration or lens shading. Keywords: digital photography, image quality evaluation, optical aberration, information capacity, camera performance database 1. INTRODUCTION The evaluation of a digital camera is a key factor for customers, whether they are vendors or final customers. It relies on many different factors as the presence or not of some functionalities, ergonomic, price, or image quality. Each separate criterion is itself quite complex to evaluate, and depends on many different factors. The case of image quality is a good illustration of this topic. -

Invention of Digital Photograph

Invention of Digital photograph Digital photography uses cameras containing arrays of electronic photodetectors to capture images focused by a lens, as opposed to an exposure on photographic film. The captured images are digitized and stored as a computer file ready for further digital processing, viewing, electronic publishing, or digital printing. Until the advent of such technology, photographs were made by exposing light sensitive photographic film and paper, which was processed in liquid chemical solutions to develop and stabilize the image. Digital photographs are typically created solely by computer-based photoelectric and mechanical techniques, without wet bath chemical processing. The first consumer digital cameras were marketed in the late 1990s.[1] Professionals gravitated to digital slowly, and were won over when their professional work required using digital files to fulfill the demands of employers and/or clients, for faster turn- around than conventional methods would allow.[2] Starting around 2000, digital cameras were incorporated in cell phones and in the following years, cell phone cameras became widespread, particularly due to their connectivity to social media websites and email. Since 2010, the digital point-and-shoot and DSLR formats have also seen competition from the mirrorless digital camera format, which typically provides better image quality than the point-and-shoot or cell phone formats but comes in a smaller size and shape than the typical DSLR. Many mirrorless cameras accept interchangeable lenses and have advanced features through an electronic viewfinder, which replaces the through-the-lens finder image of the SLR format. While digital photography has only relatively recently become mainstream, the late 20th century saw many small developments leading to its creation. -

Seeing Like Your Camera ○ My List of Specific Videos I Recommend for Homework I.E

Accessing Lynda.com ● Free to Mason community ● Set your browser to lynda.gmu.edu ○ Log-in using your Mason ID and Password ● Playlists Seeing Like Your Camera ○ My list of specific videos I recommend for homework i.e. pre- and post-session viewing.. PART 2 - FALL 2016 ○ Clicking on the name of the video segment will bring you immediately to Lynda.com (or the login window) Stan Schretter ○ I recommend that you eventually watch the entire video class, since we will only use small segments of each video class [email protected] 1 2 Ways To Take This Course What Creates a Photograph ● Each class will cover on one or two topics in detail ● Light ○ Lynda.com videos cover a lot more material ○ I will email the video playlist and the my charts before each class ● Camera ● My Scale of Value ○ Maximum Benefit: Review Videos Before Class & Attend Lectures ● Composition & Practice after Each Class ○ Less Benefit: Do not look at the Videos; Attend Lectures and ● Camera Setup Practice after Each Class ○ Some Benefit: Look at Videos; Don’t attend Lectures ● Post Processing 3 4 This Course - “The Shot” This Course - “The Shot” ● Camera Setup ○ Exposure ● Light ■ “Proper” Light on the Sensor ■ Depth of Field ■ Stop or Show the Action ● Camera ○ Focus ○ Getting the Color Right ● Composition ■ White Balance ● Composition ● Camera Setup ○ Key Photographic Element(s) ○ Moving The Eye Through The Frame ■ Negative Space ● Post Processing ○ Perspective ○ Story 5 6 Outline of This Class Class Topics PART 1 - Summer 2016 PART 2 - Fall 2016 ● Topic 1 ○ Review of Part 1 ● Increasing Your Vision ● Brief Review of Part 1 ○ Shutter Speed, Aperture, ISO ○ Shutter Speed ● Seeing The Light ○ Composition ○ Aperture ○ Color, dynamic range, ● Topic 2 ○ ISO and White Balance histograms, backlighting, etc. -

Passport Photograph Instructions by the Police

Passport photograph instructions 1 (7) Passport photograph instructions by the police These instructions describe the technical and quality requirements on passport photographs. The same instructions apply to all facial photographs used on the passports, identity cards and permits granted by the police. The instructions are based on EU legislation and international treaties. The photographer usually sends the passport photograph directly to the police electronically, and it is linked to the application with a photograph retrieval code assigned to the photograph. You can also use a paper photograph, if you submit your application at a police service point. Contents • Photograph format • Technical requirements on the photograph • Dimensions and positioning • Posture • Lighting • Expressions, glasses, head-wear and make-up • Background Photograph format • The photograph can be a black-and-white or a colour photograph. • The dimensions of photographs submitted electronically must be exactly 500 x 653 pixels. Deviations as small as one pixel are not accepted. • Electronically submitted photographs must be saved in the JPEG format (not JPEG2000). The file extension can be either .jpg or .jpeg. • The maximum size of an electronically submitted photograph is 250 kilobytes. 1. Correct 2. Correct 2 (7) Technical requirements on the photograph • The photograph must be no more than six months old. • The photograph must not be manipulated in any way that would change even the small- est details in the subject’s appearance or in a way that could raise suspicions about the photograph's authenticity. Use of digital make-up is not allowed. • The photograph must be sharp and in focus over the entire face. -

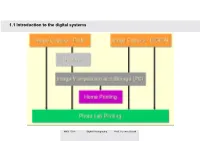

1.1 Introduction to the Digital Systems

1.1 Introduction to the digital systems PHO 130 F Digital Photography Prof. Lorenzo Guasti How a DSLR work and why we call a camera “reflex” The heart of all digital cameras is of course the digital imaging sensor. It is the component that converts the light coming from the subject you are photographing into an electronic signal, and ultimately into the digital photograph that you can view or print PHO 130 F Digital Photography Prof. Lorenzo Guasti Although they all perform the same task and operate in broadly the same way, there are in fact th- ree different types of sensor in common use today. The first one is the CCD, or Charge Coupled Device. CCDs have been around since the 1960s, and have become very advanced, however they can be slower to operate than other types of sensor. The main alternative to CCD is the CMOS, or Complimentary Metal-Oxide Semiconductor sen- sor. The main proponent of this technology being Canon, which uses it in its EOS range of digital SLR cameras. CMOS sensors have some of the signal processing transistors mounted alongside the sensor cell, so they operate more quickly and can be cheaper to make. A third but less common type of sensor is the revolutionary Foveon X3, which offers a number of advantages over conventional sensors but is so far only found in Sigma’s range of digital SLRs and its forthcoming DP1 compact camera. I’ll explain the X3 sensor after I’ve explained how the other two types work. PHO 130 F Digital Photography Prof. -

Diy Photography & Jr: Photographic Stickers

1 DIY PHOTOGRAPHY & JR: PHOTOGRAPHIC STICKERS For grade levels 3-12 Developed by: PEITER GRIGA The world now contains more photographs than bricks, and they are, astonishingly, all different. - John Szarkowski Are images the spine and rib cage of our society or are we so saturated in photography that we forget the underlying messages we ‘read’ from images? Are we protected/ supported by images or flooded by them? JR’s work elaborates on the idea of how we value images by demonstrating our likenesses and differences. This dichotomy is so great in his work; JR can eliminate himself as the artist, becoming the egoless ‘guide.’ As part of his Inside Out Project he allows people from all around the world to send him pictures they take of themselves, which he then prints out a poster sized image and returns to the image maker, who then selects a location and hangs the work in a public space. In a traditional sense, he hands the artistic power over to the participant and only controls the printing and specs for the images. The CAC participated in the Inside Out Project as early as 2011, but most recently through installations in Fountain Square, Rabbit Hash, KY, Findlay Market, and inside the CAC Lobby. The power of the image and the location of the image are vital aspects of JR’s site-specific work. Building upon these two factors is the material used to place the image in the public space. His materials usually include wheat paste, paper, and a large scale digitally printed image. -

Digital Photography: the Influence of CCD Pixel-Size on Imaging

IS&T’s 1999 PICS Conference IS&T's 1999 PICS Conference Digital Photography: The Influence of CCD Pixel Size on Imaging Performance Rodney Shaw Hewlett-Packard Research Laboratories Palo Alto, California 94304 Abstract with the question of enlargement, since this is a well-known factor in both analog and digital photography, and can be dealt As digital photography becomes increasingly competitive with with in a separate, well-established manner. traditional analog systems, questions of both comparative and The question here is the applicability of a similar global ultimate performance become of great practical relevance. In set of photographic performance parameters for any given particular the questions of camera speed and of the image digital sensor array, taking into account the complicating ex- sharpness and noise properties are of interest, especially from istence of a grid with a fixed pixel size. However to address the possibility of an opening up of new desirable areas of this question we can take the silver-halide analogy further by photographic performance with new digital technologies. considering the case where a conventional negative image is Clearly the camera format (array size, number of pixels) plays scanned as input to a digital system, which is in fact an in- a prominent role in defining overall photographic perfor- creasingly commonplace activity. In doing so the scanning mance, but it is less clear how the absolute pixel dimensions system implies placing over the film a virtual grid much akin define individual photographic parameters. This present study to the physical grid of sensor arrays. The choice of the grid uses a previously published end-to-end signal-to-noise ratio size is not seen as interfering with the global photographic model to investigate the influence of pixel size on various exposure properties, though clearly it will impose its own reso- aspects of imaging performance. -

Photographic Films

PHOTOGRAPHIC FILMS A camera has been called a “magic box.” Why? Because the box captures an image that can be made permanent. Photographic films capture the image formed by light reflecting from the surface being photographed. This instruction sheet describes the nature of photographic films, especially those used in the graphic communications industries. THE STRUCTURE OF FILM Protective Coating Emulsion Base Anti-Halation Backing Photographic films are composed of several layers. These layers include the base, the emulsion, the anti-halation backing and the protective coating. THE BASE The base, the thickest of the layers, supports the other layers. Originally, the base was made of glass. However, today the base can be made from any number of materials ranging from paper to aluminum. Photographers primarily use films with either a plastic (polyester) or paper base. Plastic-based films are commonly called “films” while paper-based films are called “photographic papers.” Polyester is a particularly suitable base for film because it is dimensionally stable. Dimensionally stable materials do not appreciably change size when the temperature or moisture- level of the film change. Films are subjected to heated liquids during processing (developing) and to heat during use in graphic processes. Therefore, dimensional stability is very important for graphic communications photographers because their final images must always match the given size. Conversely, paper is not dimen- sionally stable and is only appropriate as a film base when the “photographic print” is the final product (as contrasted to an intermediate step in a multi-step process). THE EMULSION The emulsion is the true “heart” of film. -

An Analytical Study on the Modern History of Digital Photography Keywords

203 Amr Galal An analytical study on the modern history of digital photography Dr. Amr Mohamed Galal Lecturer in Faculty of mass Communication, MISR International University (MIU) Abstract: Keywords: Since its emergence more than thirty years ago, digital photography has undergone Digital Photography rapid transformations and developments. Digital technology has produced Image Sensor (CCD-CMOS) generations of personal computers, which turned all forms of technology into a digital one. Photography received a large share in this development in the making Image Storage (Digital of cameras, sensitive surfaces, image storage, image transfer, and image quality and Memory) clarity. This technology also allowed the photographer to record all his visuals with Playback System a high efficiency that keeps abreast of the age’s requirements and methods of communication. The final form of digital technology was not reached all of a Bayer Color Filter sudden; this development – in spite of its fast pace – has been subject to many LCD display pillars, all of which have contributed to reaching the modern traditional digital Digital Viewfinder. shape of the camera and granted the photographer capabilities he can use to produce images that fulfill their task. Reaching this end before digital technology was quite difficult and required several procedures to process sensitive film and paper material and many chemical processes. Nowadays, this process is done by pushing a few buttons. This research sheds light on these main foundations for the stages of digital development according to their chronological order, along with presenting scientists or production companies that have their own research laboratories which develop and enhance their products.