Bibliographic History of the Su Wen

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Web That Has No Weaver

THE WEB THAT HAS NO WEAVER Understanding Chinese Medicine “The Web That Has No Weaver opens the great door of understanding to the profoundness of Chinese medicine.” —People’s Daily, Beijing, China “The Web That Has No Weaver with its manifold merits … is a successful introduction to Chinese medicine. We recommend it to our colleagues in China.” —Chinese Journal of Integrated Traditional and Chinese Medicine, Beijing, China “Ted Kaptchuk’s book [has] something for practically everyone . Kaptchuk, himself an extraordinary combination of elements, is a thinker whose writing is more accessible than that of Joseph Needham or Manfred Porkert with no less scholarship. There is more here to think about, chew over, ponder or reflect upon than you are liable to find elsewhere. This may sound like a rave review: it is.” —Journal of Traditional Acupuncture “The Web That Has No Weaver is an encyclopedia of how to tell from the Eastern perspective ‘what is wrong.’” —Larry Dossey, author of Space, Time, and Medicine “Valuable as a compendium of traditional Chinese medical doctrine.” —Joseph Needham, author of Science and Civilization in China “The only approximation for authenticity is The Barefoot Doctor’s Manual, and this will take readers much further.” —The Kirkus Reviews “Kaptchuk has become a lyricist for the art of healing. And the more he tells us about traditional Chinese medicine, the more clearly we see the link between philosophy, art, and the physician’s craft.” —Houston Chronicle “Ted Kaptchuk’s book was inspirational in the development of my acupuncture practice and gave me a deep understanding of traditional Chinese medicine. -

Bian Que's Viewpoint on Medicine and the Preventative Treatment of Diseases

Northeast Asia Traditional Chinese Medicine Communication and Development Base of traditional medicine in Northeast Asia, conduct academic seminars and collaborative innovation, and form annual report on development of traditional medicine in Northeast Asia. 2. Special Belt & Road scholarships for Northeast Asia: are ready to provide yearly funding support such as full & partial scholarships and grants for overseas TCM talents with medical background. 3. Exhibitions on traditional medicine in Northeast Asia: to held exhibitions on traditional medicine of northeast Asian countries, health-care foods, welfare In November 2016, the Northeast Asia Traditional equipments and service trade negotiations, and promote Chinese Medicine Communication and Development multilateral p roject cooperation. Base was established in Changchun University of Chinese Medicine being approved by the State 4. The forum on Traditional Medicine in Northeast Administration of Traditional Chinese Medicine of Asia (Planning): to invite principals of traditional China. This foundation will serve as an important medicine departments from northeast Asian or platform for the spread of TCM in northeast China. relevant countries to make keynote speeches, and distinguished specialists and experts to participate in Distinct Regional Advantages Historically, this conference discussion. area is the core of the Northern Silk Road that extends to Russia, Japan, Mongolia, Republic of Korea and 5. One journal and one bulletin: to issue restrictedly Democratic People’s Republic of Korean. The city of Northeast Asia Traditional Chinese Medicine (quarterly) Changchun aims to be a regional center in Northeast and Bulletin on Traditional Chinese Medicine Asia. The China-Northeast Asia Expo in Changchun Information in Northeast Asia (monthly). serves as an important window to open to the north. -

Some Reflections Upon the Origins of Acupuncture

POINTS IN TIME: SOME REFLECTIONS UPON THE ORIGINS OF ACUPUNCTURE WARREN M. COCHRAN Over the last decade or so of my involvement in the traditional medicine of China, both as a practitioner and an educator, a frequently asked question from patients and students alike, focuses on the antiquity and early origins of the therapeutic technique known as acupuncture. Perhaps in the efforts to afford a greater respectability to this unique method of treating human affliction, earlier proponents of this ancient art may have invented a mythological past where incipient physicians in prehistoric Chinese societies used flint, stone, and bronze needles to administer acupuncture to ailing fellow citizens as long ago as five thousand years. Unfortunately however, there is no con- clusive evidence to substantiate this claim. Extant sources suggest instead that the medical technique termed acupuncture by the Dutch physician Willem ten Rhijne in 1683, may not be much over two thousand years old. I hasten to add that this conclusion does not of course, lessen the therapeutic importance of what appears to be the most recent of the traditional Chinese healing modalities. In this paper I propose to assess the validity of this evidence and consider the hypothesis that acupuncture evolved from notions of demonic medicine and was in turn, antedated by the therapeutic exigencies of bloodletting. The evidence to be reviewed will take the following forms: ( 1 ) Needles or needle-shaped instruments from archaeological sites in early China. ( 2 ) A stone tomb relief from the Later Han Period. ( 3 ) A purported acupuncture model from an early Han tomb. -

Ssu K'u Ch'üan Shu, Its Continuing Series and Selections, and Their Acquisitions in North America

Journal of East Asian Libraries Volume 1998 Number 116 Article 5 10-1-1998 Ssu k'u ch'üan shu, Its Continuing Series and Selections, and Their Acquisitions in North America Guoqing Li Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/jeal BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Li, Guoqing (1998) "Ssu k'u ch'üan shu, Its Continuing Series and Selections, and Their Acquisitions in North America," Journal of East Asian Libraries: Vol. 1998 : No. 116 , Article 5. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/jeal/vol1998/iss116/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of East Asian Libraries by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. SSUKUssukvchuanshuch17anshu continuing SERIES selections acquisitions NORTH AMERICAAMIERICA guoguoqingqing li ohio state university ssu kuvu chuan shu great source cainaschinas literary cultural tradition compilation ssu vuk u ch gianfianuan shu Q jfsjsjisjib complete library four categories greatest event cainaschinas publishing history 3800 chinese scholars worked ten years 177217811772 1781 project undertaken order emperor chien lung 13254 titles collected country valuable titles 3461 total selected ssu kuvu chlianchfianch uan shu 6793 titles left Ts un mu 4-9 political reasons 3000 titles rejecterejectedd destroyed either totally partially mainly political reasons 1 see chart 1 chart I1 ssu kuvu collections -

The Later Han Empire (25-220CE) & Its Northwestern Frontier

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2012 Dynamics of Disintegration: The Later Han Empire (25-220CE) & Its Northwestern Frontier Wai Kit Wicky Tse University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the Asian History Commons, Asian Studies Commons, and the Military History Commons Recommended Citation Tse, Wai Kit Wicky, "Dynamics of Disintegration: The Later Han Empire (25-220CE) & Its Northwestern Frontier" (2012). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 589. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/589 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/589 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Dynamics of Disintegration: The Later Han Empire (25-220CE) & Its Northwestern Frontier Abstract As a frontier region of the Qin-Han (221BCE-220CE) empire, the northwest was a new territory to the Chinese realm. Until the Later Han (25-220CE) times, some portions of the northwestern region had only been part of imperial soil for one hundred years. Its coalescence into the Chinese empire was a product of long-term expansion and conquest, which arguably defined the egionr 's military nature. Furthermore, in the harsh natural environment of the region, only tough people could survive, and unsurprisingly, the region fostered vigorous warriors. Mixed culture and multi-ethnicity featured prominently in this highly militarized frontier society, which contrasted sharply with the imperial center that promoted unified cultural values and stood in the way of a greater degree of transregional integration. As this project shows, it was the northwesterners who went through a process of political peripheralization during the Later Han times played a harbinger role of the disintegration of the empire and eventually led to the breakdown of the early imperial system in Chinese history. -

The Historical Roots of Technical Communication in the Chinese Tradition

The Historical Roots of Technical Communication in the Chinese Tradition The Historical Roots of Technical Communication in the Chinese Tradition By Daniel Ding The Historical Roots of Technical Communication in the Chinese Tradition By Daniel Ding This book first published 2020 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2020 by Daniel Ding All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-5275-5782-0 ISBN (13): 978-1-5275-5782-6 To Karen Lo: My Lovely Wife and Supporter “Thy fruit abundant fall!” —Classic of Poetry TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter One ................................................................................................ 1 Technical Writing in Chinese Antiquity: An Introduction Chapter Two ............................................................................................. 21 The Oracle-Bone Inscriptions (甲骨文): The Earliest Artifact of Technical Writing in China Chapter Three ........................................................................................... 37 Classic of Poetry (诗经): Technical Instructions and Reports Chapter Four ............................................................................................ -

Three Kingdoms Unveiling the Story: List of Works

Celebrating the 40th Anniversary of the Japan-China Cultural Exchange Agreement List of Works Organizers: Tokyo National Museum, Art Exhibitions China, NHK, NHK Promotions Inc., The Asahi Shimbun With the Support of: the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan, NATIONAL CULTURAL HERITAGE ADMINISTRATION, July 9 – September 16, 2019 Embassy of the People’s Republic of China in Japan With the Sponsorship of: Heiseikan, Tokyo National Museum Dai Nippon Printing Co., Ltd., Notes Mitsui Sumitomo Insurance Co.,Ltd., MITSUI & CO., LTD. ・Exhibition numbers correspond to the catalogue entry numbers. However, the order of the artworks in the exhibition may not necessarily be the same. With the cooperation of: ・Designation is indicated by a symbol ☆ for Chinese First Grade Cultural Relic. IIDA CITY KAWAMOTO KIHACHIRO PUPPET MUSEUM, ・Works are on view throughout the exhibition period. KOEI TECMO GAMES CO., LTD., ・ Exhibition lineup may change as circumstances require. Missing numbers refer to works that have been pulled from the JAPAN AIRLINES, exhibition. HIKARI Production LTD. No. Designation Title Excavation year / Location or Artist, etc. Period and date of production Ownership Prologue: Legends of the Three Kingdoms Period 1 Guan Yu Ming dynasty, 15th–16th century Xinxiang Museum Zhuge Liang Emerges From the 2 Ming dynasty, 15th century Shanghai Museum Mountains to Serve 3 Narrative Figure Painting By Qiu Ying Ming dynasty, 16th century Shanghai Museum 4 Former Ode on the Red Cliffs By Zhang Ruitu Ming dynasty, dated 1626 Tianjin Museum Illustrated -

11. Ts'ung-Shu

Handbook of Reference Works in Traditional Chinese Studies (R. Eno, 2011) 11. TS’UNG-SHU Ts’ung-shu 叢書 (sometimes referred to as “collectanea”) are collections of independent works that are published together in order to preserve them, to market them effectively, or to present a unified series edition. Ts’ung-shu may be, and most often are, miscellaneous collections, but there are many that are published to give broader circulation to the writings of one person, one family, or one locality, to collect editions or commentaries of a single work or group of works, or to bring together a number of works related by subject or genre. In this respect, many ts’ung-shu resemble anthologies. Although there is some conceptual overlap between the two genres, ts’ung-shu are, strictly speaking, collections only of entire independent books, rather than collections of sections, stories, poems, or prefaces selected from the larger works of which they originally formed a part. This distinction is sometimes blurred, but is generally unambiguous. The philologist Lo Chen-yü 羅振玉, himself the compiler of several ts’ung-shu, claimed that ts’ung-shu had flourished in China since early Chou times, when texts were cast on bronze. While this may be an exaggeration, Lo was correct in noting that the Han Dynasty “stone classics” stele monuments constituted an early ts’ung-shu, as did the Imperially commissioned “Nine Classics” project of the T’ang period. It is perfectly reasonable to view pre-Ch’in compendia such as the Lü-shih ch’un-ch’iu 呂氏春秋 and the Kuan Tzu 管子 as ts’ung-shu, and in their early bamboo forms they would have appeared as huge and encyclopedic as the Ssu-k’u collection does today. -

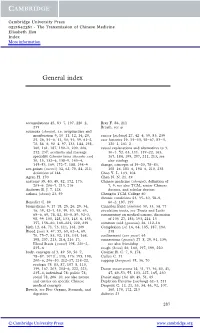

General Index 287

Cambridge University Press 0521642361 - The Transmission of Chinese Medicine Elisabeth Hsu Index More information General index 287 General index accumulations 45, 83–7, 197, 220–2, Bray F. 86, 211 235 Breath, see qi acumoxa (zhenjiu), i.e. acupuncture and moxibustion 9, 10–11, 12, 14, 20, cancer (aizheng) 27, 42–4, 59, 83, 239 25, 26, 34–6, 41, 50, 54, 59, 61–2, case histories 19, 34–44, 58–67, 83–4, 70, 84–6, 90–4, 97, 133, 144, 158, 120–1, 161–2 160, 161, 187, 190–1, 200, 206, causal explanations and alternatives to 3, 212, 237; acumoxa and massage 30–1, 52, 63, 111, 119–22, 163, speciality (zhenjiu tuina zhuanke xue) 167, 184, 199, 207, 211, 213; see 10, 15, 132–6, 138–9, 143–4, also etiology 145–53, 169, 172–7, 188, 198–9 change, concepts of 19–20, 78–83, acu-points (xuewei) 34, 62, 70, 84, 211; 108–16, 181–6, 194–6, 210, 238 definition of 144 Chao Y. L. 103, 104 Agren H. 170 Chen N. N. 21, 49 anatomy 39, 40, 49, 82, 172, 173, Chinese medicine (zhongyi), definition of 205–6, 206–7, 213, 216 7, 9; see also TCM, senior Chinese Andrews B. J. 7, 128 doctors, and scholar doctors asthma (chuan) 23, 59 Chengdu TCM College 60 chronic conditions 23, 35– 40, 58–9, Benedict C. 89 60–2, 197, 199 biomedicine 9, 17–18, 25, 26, 29, 34, Cinnabar Field (dantian) 30, 33, 34, 77 36, 39, 42–3, 45, 49, 50, 58, 63, circulation tracts, see Tracts and Links 65–6, 69, 78, 82, 83–5, 89, 92–3, commentary on medical canons, discussion 98, 99–100, 128, 133, 145–6, 155, of 105–27, 186, 193, 214–15 157, 158–60, 168–224, 229, 239 common cold (ganmao) 26, 112–16 birth 12, 64, 71, 73, 111, 161, 209 Complexion (se) 16, 64, 185, 187, 190, Blood (xue) 3, 47, 55, 60, 62–4, 69, 218 70, 75–7, 83, 92, 118, 144, 168, confinement (zuo yuezi) 64 198, 207, 213, 214, 216–17; connections (guanxi) 27–8, 29, 91, 139; Blood Stasis ( yuxue) 198, 220–2, see also friendship 235–6 cough (kesou) 26, 160, 197, 199, 220 body, concepts of 3, 49–50, 56–7, Croizier R. -

Daily Life for the Common People of China, 1850 to 1950

Daily Life for the Common People of China, 1850 to 1950 Ronald Suleski - 978-90-04-36103-4 Downloaded from Brill.com04/05/2019 09:12:12AM via free access China Studies published for the institute for chinese studies, university of oxford Edited by Micah Muscolino (University of Oxford) volume 39 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/chs Ronald Suleski - 978-90-04-36103-4 Downloaded from Brill.com04/05/2019 09:12:12AM via free access Ronald Suleski - 978-90-04-36103-4 Downloaded from Brill.com04/05/2019 09:12:12AM via free access Ronald Suleski - 978-90-04-36103-4 Downloaded from Brill.com04/05/2019 09:12:12AM via free access Daily Life for the Common People of China, 1850 to 1950 Understanding Chaoben Culture By Ronald Suleski leiden | boston Ronald Suleski - 978-90-04-36103-4 Downloaded from Brill.com04/05/2019 09:12:12AM via free access This is an open access title distributed under the terms of the prevailing cc-by-nc License at the time of publication, which permits any non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited. An electronic version of this book is freely available, thanks to the support of libraries working with Knowledge Unlatched. More information about the initiative can be found at www.knowledgeunlatched.org. Cover Image: Chaoben Covers. Photo by author. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Suleski, Ronald Stanley, author. Title: Daily life for the common people of China, 1850 to 1950 : understanding Chaoben culture / By Ronald Suleski. -

Flowers Bloom and Fall

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by ASU Digital Repository Flowers Bloom and Fall: Representation of The Vimalakirti Sutra In Traditional Chinese Painting by Chen Liu A Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirement for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy Approved November 2011 by the Graduate Supervisory Committee: Claudia Brown, Chair Ju-hsi Chou Jiang Wu ARIZONA STATE UNIVERSITY December 2011 ABSTRACT The Vimalakirti Sutra is one of the classics of early Indian Mahayana Buddhism. The sutra narrates that Vimalakirti, an enlightened layman, once made it appear as if he were sick so that he could demonstrate the Law of Mahayana Buddhism to various figures coming to inquire about his illness. This dissertation studies representations of The Vimalakirti Sutra in Chinese painting from the fourth to the nineteenth centuries to explore how visualizations of the same text could vary in different periods of time in light of specific artistic, social and religious contexts. In this project, about forty artists who have been recorded representing the sutra in traditional Chinese art criticism and catalogues are identified and discussed in a single study for the first time. A parallel study of recorded paintings and some extant ones of the same period includes six aspects: text content represented, mode of representation, iconography, geographical location, format, and identity of the painter. This systematic examination reveals that two main representational modes have formed in the Six Dynasties period (220-589): depictions of the Great Layman as a single image created by Gu Kaizhi, and narrative illustrations of the sutra initiated by Yuan Qian and his teacher Lu Tanwei. -

The Seal of the Unity of the Three SAMPLE

!"# $#%& '( !"# )*+!, '( !"# !"-## By the same author: Great Clarity: Daoism and Alchemy in Early Medieval China (Stanford University Press, 2006) The Encyclopedia of Taoism, editor (Routledge, 2008) Awakening to Reality: The “Regulated Verses” of the Wuzhen pian, a Taoist Classic of Internal Alchemy (Golden Elixir Press, 2009) Fabrizio Pregadio The Seal of the Unity of the Three A Study and Translation of the Cantong qi, the Source of the Taoist Way of the Golden Elixir Golden Elixir Press This sample contains parts of the Introduction, translations of 9 of the 88 sections of the Cantong qi, and parts of the back matter. For other samples and more information visit this web page: www.goldenelixir.com/press/trl_02_ctq.html Golden Elixir Press, Mountain View, CA www.goldenelixir.com [email protected] © 2011 Fabrizio Pregadio ISBN 978-0-9843082-7-9 (cloth) ISBN 978-0-9843082-8-6 (paperback) All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations, no part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Typeset in Sabon. Text area proportioned in the Golden Section. Cover: The Chinese character dan 丹 , “Elixir.” To Yoshiko Contents Preface, ix Introduction, 1 The Title of the Cantong qi, 2 A Single Author, or Multiple Authors?, 5 The Dating Riddle, 11 The Three Books and the “Ancient Text,” 28 Main Commentaries, 33 Dao, Cosmos, and Man, 36 The Way of “Non-Doing,” 47 Alchemy in the Cantong qi, 53 From the External Elixir to the Internal Elixir, 58 Translation, 65 Book 1, 69 Book 2, 92 Book 3, 114 Notes, 127 Textual Notes, 231 Tables and Figures, 245 Appendixes, 261 Two Biographies of Wei Boyang, 263 Chinese Text, 266 Index of Main Subjects, 286 Glossary of Chinese Characters, 295 Works Quoted, 303 www.goldenelixir.com/press/trl_02_ctq.html www.goldenelixir.com/press/trl_02_ctq.html Introduction “The Cantong qi is the forefather of the scriptures on the Elixir of all times.