Physiography, Topography and Geology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Montgomery Township N.R.I. Appendix – Nitrate Dilution

Nitrate Dilution Modeling of Montgomery Township, Somerset County, NJ Prepared for: Montgomery Township Environmental Commission Somerset County, NJ 2261 Route 206 Belle Mead, NJ 08502 Prepared by: The GIS Center Stony Brook-Millstone Watershed Association 31 Titus Mill Road Pennington, NJ 08534 April 8, 2004 Introduction Nitrate from natural sources generally only occurs in ground water at low levels but anthropogenic sources can lead to elevated concentrations. Sources include fertilizers, animal waste, and sewage effluent. Nitrate is considered a contaminant in ground water because of various impacts to human health and aquatic ecology. For instance, high levels of nitrate intake in infants can lead to methemoglobinemia, or blue baby syndrome (Hem, 1985; U.S. EPA, 1991). Because of its low natural occurrence and solubility and stability in groundwater, nitrate can also serve as an indicator for possible bacterial, viral, or chemical contaminants of anthropogenic origin. Nitrogen is present in septic system effluent and is converted to nitrate through biological processes active in the soil below the drain field. Once this nitrification process is complete, nitrate is a stable and mobile compound in ground water under normal conditions (Hoffman and Canace, 2001). Nitrate concentrations resulting from septic effluent are mitigated by dilution if the septic effluent is combined over time with water entering the ground through infiltration during and after storm events. The extent of this dilution effect is clearly dependent on long-term rates of both infiltration and nitrate loading from septic system sources. The density of septic systems relative to infiltration rates in a particular area is therefore a critical factor controlling the ultimate nitrate level in ground water. -

RI37 Stratigraphic Nomenclature Of

,--' ( UNIVERSITY OF DELAWARE DELAWARE GEOLOGICAL SURVEY REPORT OF INVESTIGATIONS NO.37 STRATIGRAPHIC NOMENCLATURE OF NONMARINE CRETACEOUS ROCKS OF INNER MARGIN OF COASTAL PLAIN IN DELAWARE AND ADJACENT STATES BY ROBERT R. JORDAN STATE OF DELAWARE.. NEWARK, DELAWARE JUNE 1983 STRATIGRAPHIC NOMENCLATURE OF NONMARINE CRETACEOUS ROCKS OF INNER MARGIN OF COASTAL PLAIN IN DELAWARE AND ADJACENT STATES By Robert R. Jordan Delaware Geological Survey June 1983 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ABSTRACT. ....... 1 INTRODUCTION ..... 2 Purpose and Scope. 2 Acknowledgments.. 4 REGIONAL SETTING. 4 Regional Relationships . 4 Structural Features. 5 DESCRIPTIONS OF UNITS .. 8 Historical Summary 8 Potomac Formation. 13 Nomenclature. 13 Extent. 13 Lithology . 14 Patuxent Formation . 18 Nomenclature. 18 Extent.. 18 Lithology .... 18 Arundel Formation. 19 Nomenclature.. 19 Extent. .• 19 Lithology • 20 Page Patapsco Formation. .. 20 Nomenclature . 20 Extent .. 20 Lithology.. 20 Raritan Formation . 21 Nomenclature .. 21 Extent .. 22 Lithology.. 23 Magothy Formation .. 24 Nomenclature . 24 Extent .. 24 Lithology.. 25 ENVIRONMENTS OF DEPOSITION 28 AGES .... 29 SUBDIVISIONS AND CORRELATIONS .. 32 REFERENCES . 34 ILLUSTRATIONS Figure 1. Geologic map of nonmarine Cretaceous deposits .. ..•.• •.. 3 2. Structural features of the Coastal Plain. ............ 6 3. Schematic diagram of lateral and vertical relationships of nonmarine Cretaceous deposits•....•... 34 TABLES Page Table 1. Usage of group and formation names. 9 STRATIGRAPHIC NOMENCLATURE OF NONMARINE CRETACEOUS ROCKS OF INNER MARGIN OF COASTAL PLAIN IN DELAWARE AND ADJACENT STATES ABSTRACT Rocks of Cretaceous age deposited in continental and marginal environments, and now found along the inner edge of the northern Atlantic Coastal Plain, have historically been classified as the Potomac Group and the Potomac, Patuxent, Arundel, Patapsco, Raritan, and Magothy forma tions. -

NEW JERSEY History GUIDE

NEW JERSEY HISTOry GUIDE THE INSIDER'S GUIDE TO NEW JERSEY'S HiSTORIC SitES CONTENTS CONNECT WITH NEW JERSEY Photo: Battle of Trenton Reenactment/Chase Heilman Photography Reenactment/Chase Heilman Trenton Battle of Photo: NEW JERSEY HISTORY CATEGORIES NEW JERSEY, ROOTED IN HISTORY From Colonial reenactments to Victorian architecture, scientific breakthroughs to WWI Museums 2 monuments, New Jersey brings U.S. history to life. It is the “Crossroads of the American Revolution,” Revolutionary War 6 home of the nation’s oldest continuously Military History 10 operating lighthouse and the birthplace of the motion picture. New Jersey even hosted the Industrial Revolution 14 very first collegiate football game! (Final score: Rutgers 6, Princeton 4) Agriculture 19 Discover New Jersey’s fascinating history. This Multicultural Heritage 22 handbook sorts the state’s historically significant people, places and events into eight categories. Historic Homes & Mansions 25 You’ll find that historic landmarks, homes, Lighthouses 29 monuments, lighthouses and other points of interest are listed within the category they best represent. For more information about each attraction, such DISCLAIMER: Any listing in this publication does not constitute an official as hours of operation, please call the telephone endorsement by the State of New Jersey or the Division of Travel and Tourism. numbers provided, or check the listed websites. Cover Photos: (Top) Battle of Monmouth Reenactment at Monmouth Battlefield State Park; (Bottom) Kingston Mill at the Delaware & Raritan Canal State Park 1-800-visitnj • www.visitnj.org 1 HUnterdon Art MUseUM Enjoy the unique mix of 19th-century architecture and 21st- century art. This arts center is housed in handsome stone structure that served as a grist mill for over a hundred years. -

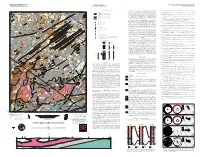

Bedrock Geologic Map of the Monmouth Junction Quadrangle, Water Resources Management U.S

DEPARTMENT OF ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION Prepared in cooperation with the BEDROCK GEOLOGIC MAP OF THE MONMOUTH JUNCTION QUADRANGLE, WATER RESOURCES MANAGEMENT U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY SOMERSET, MIDDLESEX, AND MERCER COUNTIES, NEW JERSEY NEW JERSEY GEOLOGICAL AND WATER SURVEY NATIONAL GEOLOGIC MAPPING PROGRAM GEOLOGICAL MAP SERIES GMS 18-4 Cedar EXPLANATION OF MAP SYMBOLS cycle; lake level rises creating a stable deep lake environment followed by a fall in water level leading to complete Cardozo, N., and Allmendinger, R. W., 2013, Spherical projections with OSXStereonet: Computers & Geosciences, v. 51, p. 193 - 205, doi: 74°37'30" 35' Hill Cem 32'30" 74°30' 5 000m 5 5 desiccation of the lake. Within the Passaic Formation, organic-rick black and gray beds mark the deep lake 10.1016/j.cageo.2012.07.021. 32 E 33 34 535 536 537 538 539 540 541 490 000 FEET 542 40°30' 40°30' period, purple beds mark a shallower, slightly less organic-rich lake, and red beds mark a shallow oxygenated 6 Contacts 100 M Mettler lake in which most organic matter was oxidized. Olsen and others (1996) described the next longer cycle as the Christopher, R. A., 1979, Normapolles and triporate pollen assemblages from the Raritan and Magothy formations (Upper Cretaceous) of New 6 A 100 I 10 N Identity and existance certain, location accurate short modulating cycle, which is made up of five Van Houten cycles. The still longer in duration McLaughlin cycles Jersey: Palynology, v. 3, p. 73-121. S T 44 000m MWEL L RD 0 contain four short modulating cycles or 20 Van Houten cycles (figure 1). -

Rock Climbing Inventory of NJ's State Parks and Forest

Allamuchy Mountain, Stephens State Park Rock Climbing Inventory of NJ’s State Parks and Forest Prepared by Access NJ Contents Photo Credit: Matt Carlardo www.climbnj.com June, 2006 CRI 2007 Access NJ Scope of Inventory I. Climbing Overview of New Jersey Introduction NJ’s Climbing Resource II. Rock-Climbing and Cragging: New Jersey Demographics NJ's Climbing Season Climbers and the Environment Tradition of Rock Climbing on the East Coast III. Climbing Resource Inventory C.R.I. Matrix of NJ State Lands Climbing Areas IV. Climbing Management Issues Awareness and Issues Bolts and Fixed Anchors Natural Resource Protection V. Appendix Types of Rock-Climbing (Definitions) Climbing Injury Patterns and Injury Epidemiology Protecting Raptor Sites at Climbing Areas Position Paper 003: Climbers Impact Climbers Warning Statement VI. End-Sheets NJ State Parks Adopt a Crag 2 www.climbnj.com CRI 2007 Access NJ Introduction In a State known for its beaches, meadowlands and malls, rock climbing is a well established year-round, outdoor, all weather recreational activity. Rock Climbing “cragging” (A rock-climbers' term for a cliff or group of cliffs, in any location, which is or may be suitable for climbing) in NJ is limited by access. Climbing access in NJ is constrained by topography, weather, the environment and other variables. Climbing encounters access issues . with private landowners, municipalities, State and Federal Governments, watershed authorities and other landowners and managers of the States natural resources. The motives and impacts of climbers are not distinct from hikers, bikers, nor others who use NJ's open space areas. Climbers like these others, seek urban escape, nature appreciation, wildlife observation, exercise and a variety of other enriching outcomes when we use the resources of the New Jersey’s State Parks and Forests (Steve Matous, Access Fund Director, March 2004). -

Water Resources of Oley Township, Berks County, Pennsylvania Were Studied by the U.S

WATER RESOURCES OF OLEY TOWNSHIP, BERKS COUNTY, PENNSYLVANIA By Gary N. Paulachok and Charles R. Wood U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Water-Resources Investigations Report 87-4065 Prepared in cooperation with the OLEY TOWNSHIP SUPERVISORS Harrisburg, Pennsylvania 1988 DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR DONALD PAUL MODEL, Secretary U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Dallas L. Peck, Director For additional information Copies of this report may be write to: purchased from: District Chief U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Geological Survey Books and Open-File Reports Section 4th Floor, Federal Building Federal Center P.O. Box 1107 Box 25425 Harrisburg, PA 17108-1107 Denver, Colorado 80225 ii CONTENTS Page Abstract................................................................ 1 Introduction............................................................ 2 Purpose and scope................................................... 2 Description of area................................................. 2 Physical and cultural setting.................................. 2 Climate and precipitation...................................... 4 Geologic setting............................................... 5 Water supply and wastewater treatment............................... 6 We11-numbering system............................................... 7 Geologic names and aquifer codes.................................... 7 Acknowledgments..................................................... 8 Surface-water resources................................................. 8 Drainage basins and streamflow..................................... -

A Dinosaur Track from New Jersey at the State Museum in Trenton

New Jersey Geological and Water Survey Information Circular What's in a Rock? A Dinosaur Track from New Jersey at the State Museum in Trenton Introduction a large dinosaur track (fig. 2) on the bottom. Most of the rock is sedimentary, sandstone from the 15,000-foot-thick Passaic A large, red rock in front of the New Jersey State Museum Formation. The bottom part is igneous, lava from the 525-foot- (NJSM) in Trenton (fig. 1) is more than just a rock. It has a thick Orange Mountain Basalt, which overspread the Passaic fascinating geological history. This three-ton slab, was excavated Formation. (The overspreading lava was originally at the top of from a construction site in Woodland Park, Passaic County. It the rock, but the rock is displayed upside down to showcase the was brought to Trenton in 2010 and placed upside down to show dinosaur footprint). The rock is about 200 million years old, from the Triassic footprints Period of geologic time. It formed in a rift valley, the Newark Passaic Formation Basin, when Africa, positioned adjacent to the mid-Atlantic states, began to pull eastward and North America began to pull westward contact to open the Atlantic Ocean. The pulling and stretching caused faults to move and the rift valley to subside along border faults including the Ramapo Fault of northeastern New Jersey, about 8 miles west of Woodland Park. Sediments from erosion of higher Collection site Orange Mountain Basalt top N Figure 1. Rock at the New Jersey State Museum. Photo by W. Kuehne Adhesion ripples DESCRIPTION OF MAP UNITS 0 1 2 mi Orange Mountain Basalt L 32 cm Jo (Lower Jurassic) 0 1 2 km W 25.4 cm contour interval 20 feet ^p Passaic Formation (Upper Triassic) Figure 3. -

New Jersey State Research Guide Family History Sources in the Garden State

New Jersey State Research Guide Family History Sources in the Garden State New Jersey History After Henry Hudson’s initial explorations of the Hudson and Delaware River areas, numerous Dutch settlements were attempted in New Jersey, beginning as early as 1618. These settlements were soon abandoned because of altercations with the Lenni-Lenape (or Delaware), the original inhabitants. A more lasting settlement was made from 1638 to 1655 by the Swedes and Finns along the Delaware as part of New Sweden, and this continued to flourish although the Dutch eventually Hessian Barracks, Trenton, New Jersey from U.S., Historical Postcards gained control over this area and made it part of New Netherland. By 1639, there were as many as six boweries, or small plantations, on the New Jersey side of the Hudson across from Manhattan. Two major confrontations with the native Indians in 1643 and 1655 destroyed all Dutch settlements in northern New Jersey, and not until 1660 was the first permanent settlement established—the village of Bergen, today part of Jersey City. Of the settlers throughout the colonial period, only the English outnumbered the Dutch in New Jersey. When England acquired the New Netherland Colony from the Dutch in 1664, King Charles II gave his brother, the Duke of York (later King James II), all of New York and New Jersey. The duke in turn granted New Jersey to two of his creditors, Lord John Berkeley and Sir George Carteret. The land was named Nova Caesaria for the Isle of Jersey, Carteret’s home. The year that England took control there was a large influx of English from New England and Long Island who, for want of more or better land, settled the East Jersey towns of Elizabethtown, Middletown, Piscataway, Shrewsbury, and Woodbridge. -

Water Resources of the New Jersey Part of the Ramapo River Basin

Water Resources of the New Jersey Part of the Ramapo River Basin GEOLOGICAL SURVEY WATER-SUPPLY PAPER 1974 Prepared in cooperation with the New Jersey Department of Conservation and Economic Development, Division of Water Policy and Supply Water Resources of the New Jersey Part of the Ramapo River Basin By JOHN VECCHIOLI and E. G. MILLER GEOLOGICAL SURVEY WATER-SUPPLY PAPER 1974 Prepared in cooperation with the New Jersey Department of Conservation and Economic Development, Division of Water Policy and Supply UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, WASHINGTON : 1973 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR ROGERS C. B. MORTON, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY V. E. McKelvey, Director Library of Congress catalog-card No. 72-600358 For sale bv the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Washington, D.C. 20402 - Price $2.20 Stock Number 2401-02417 CONTENTS Page Abstract.................................................................................................................. 1 Introduction............................................................................................ ............ 2 Purpose and scope of report.............................................................. 2 Acknowledgments.......................................................................................... 3 Previous studies............................................................................................. 3 Geography...................................................................................................... 4 Geology -

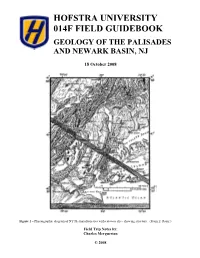

Hofstra University 014F Field Guidebook Geology of the Palisades and Newark Basin, Nj

HOFSTRA UNIVERSITY 014F FIELD GUIDEBOOK GEOLOGY OF THE PALISADES AND NEWARK BASIN, NJ 18 October 2008 Figure 1 – Physiographic diagram of NY Metropolitan area with cutaway slice showing structure. (From E. Raisz.) Field Trip Notes by: Charles Merguerian © 2008 2 CONTENTS CONTENTS..................................................................................................................................... i INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................................... 1 GEOLOGIC BACKGROUND....................................................................................................... 4 PHYSIOGRAPHIC SETTING................................................................................................... 4 BEDROCK UNITS..................................................................................................................... 7 Layers I and II: Pre-Newark Complex of Paleozoic- and Older Rocks.................................. 8 Layer V: Newark Strata and the Palisades Intrusive Sheet.................................................. 12 General Geologic Relationships ....................................................................................... 12 Stratigraphic Relationships ............................................................................................... 13 Paleogeographic Relationships ......................................................................................... 16 Some Relationships Between Water and Sediment......................................................... -

Evaluation of Groundwater Resources of Greenwich Township, Warren County, New Jersey

Evaluation of Groundwater Resources of Greenwich Township, Warren County, New Jersey M2 Associates Inc. 56 Country Acres Drive Hampton, New Jersey 08827 (908) 238-0827 EVALUATION OF GROUNDWATER RESOURCES OF GREENWICH TOWNSHIP, WARREN COUNTY,NEW JERSEY NOVEMBER 8, 2005 Prepared for: Greenwich Township Planning Board 321 Greenwich Street Stewartsville, New Jersey 08886 Prepared by: Matthew J. Mulhall, P.G. M2 Associates Inc. 56 Country Acres Drive Hampton, New Jersey 08827 (908) 238-0827 EVALUATION OF GROUNDWATER RESOURCES OF GREENWICH TOWNSHIP, WARREN COUNTY,NEW JERSEY TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION............................................................................................................. 1 GEOLOGY ...................................................................................................................... 5 LOCATION ..................................................................................................................... 5 POPULATION DENSITY.................................................................................................... 6 PHYSIOGRAPHIC PROVINCE ............................................................................................ 6 TOPOGRAPHY ................................................................................................................ 6 SURFACE WATER .......................................................................................................... 7 Watersheds............................................................................................................ -

Ii. Natural Resources of the Greenwood Lake Watershed

II. NATURAL RESOURCES II. NATURAL RESOURCES OF THE GREENWOOD LAKE WATERSHED A. LAND RESOURCES Geologic History The Greenwood Lake Watershed is located in the Highlands Physiographic Province, as shown in Figure II.A-1. The Highlands are underlain by the oldest rocks in New Jersey. These Precambrian igneous and metamorphic rocks were formed between 1.3 billion and 750 million years ago by the melting and recrystallization of sedimentary rocks that were deeply buried, subjected to high pressure and temperature, and intensely deformed.1 The Precambrian rocks are interrupted by several elongate northeast-southwest trending belts of folded Paleozoic sedimentary rocks equivalent to the rocks of the Valley and Ridge Province. Figure II.A-1 - Physiographic Provinces of New Jersey 1 New Jersey Geological Survey, NJ Department of Environmental Protection. 1999. The Geology of New Jersey. II-1 II. NATURAL RESOURCES The Highlands ridges in New Jersey are a southward continuation of the Green or Taconic Mountains of Vermont and Massachusetts, the New England Upland of Connecticut, and the Hudson Highlands of New York.2 The ridges continue through Pennsylvania to the vicinity of Reading. This Reading Prong of the New England Physiographic Province plunges beneath the surface of younger rocks for a distance of about fifty miles southwest of Reading and reappears where the northern end of the Blue Ridge Mountains begins to rise above the surrounding country. The Blue Ridge Mountains of the Virginia Appalachians, the mountains of New England, and the Highlands of New Jersey and New York all have a similar geologic history and character. Topography The granites and gneisses of the Highlands are resistant to erosion and create a hilly upland dissected by the deep, steep-sided valleys of major streams.3 The Highlands can be characterized as broad high ridges composed of complex folded and faulted crystalline rocks and separated by deep narrow valleys.4 The topography follows the northeast-southwest trend of the geologic structure and rock formations.