The Natural Landscape

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Second Local Implementation Plan

London Borough of Richmond upon Thames SECOND LOCAL IMPLEMENTATION PLAN CONTENTS 1. Introduction and Overview............................................................................................. 6 1.1 Richmond in Context............................................................................................. 6 1.2 Richmond’s Environment...................................................................................... 8 1.3 Richmond’s People............................................................................................... 9 1.4 Richmond’s Economy ......................................................................................... 10 1.5 Transport in Richmond........................................................................................ 11 1.5.1 Road ................................................................................................................... 11 1.5.2 Rail and Underground......................................................................................... 12 1.5.3 Buses.................................................................................................................. 13 1.5.4 Cycles ................................................................................................................. 14 1.5.5 Walking ............................................................................................................... 15 1.5.6 Bridges and Structures ....................................................................................... 15 1.5.7 Noise -

A Walk Round Teddington 2

A WALK IN TEDDINGTON: 2 The Grove Estate and Teddington Lock Start and finish at the Ferry Road traffic lights (1). This walk is approx. 2.7 miles in total Ferry Road goes to the river in one direction and to the High Street past the church in the other; Kingston Road goes off towards Kingston, and Manor Road (2) heads to Twickenham. Manor Road was built some time after 1860. Before then, the old road from Kingston to Twickenham made the sharp turn round the church from Kingston Road to Twickenham Road. The church of St Mary with St Alban (3) was the old parish church of St Mary, parts dating from the 16th century. During the incumbency of the Rev Stephen Hales (1709-61) much rebuilding was carried out, the north aisle and the tower being added. The church was continually too small for the increasing population, and in the 19th century more enlargements were carried out until a new church seemed to be the only solution. So the church of St Alban the Martyr (4) was built on the opposite side of the road. The building, which is in the French Gothic style on the scale of a cathedral, was opened in July 1896. When the new church was opened the old one was closed, but not everybody liked the new church and by popular demand St Mary’s was repaired and services were held in both churches until 1972. But by this time the number of worshippers had diminished and running expenses had risen, meaning that two churches could no longer be maintained. -

River Thames Kingston

MIN. 1 MIN. MIN. MIN. MIN. 4 MIN T ASE 1 CAUTION COMING BACK TO THE PONTOON Be aware of boat traffic. 2 40 MIN TO BASE RED MARKING 1. Keep an eye out for GoBoat crew. If It is prohibited to sail in areas there is a space free on the pontoon, a marked with red. crew member will wave to you signal- ling to make your way towards them. DOWN STREAM TRAFFIC MIN. Keep to the right and give way 2. If there is not a space, go around to all river users. the bridge and keep an eye out for the GoBoat crew’s signal for you 2 UP STREAM TRAFFIC to come in. Follow instructions at bridges. 3. Keep to the right hand side of the BOAT MOORINGS river until it is safe to cross. If you are The brown areas along the river. coming from Hampton Court Palace Keep a distance. you will not have to cross. If you are 3 coming from Teddington, go through HIGH WIND both bridges. Please do not stop near Use power and steer into the the arches. Keep going beyond the 3 wind to keep control. bridge and only start to cross when MIN. you have space and it is safe to do so. CONGESTED AREAS MIN. Be aware of more boats around. 4. Slowly approach the pontoon head-on, DO NOT attempt HORN SIGNALS to reverse in. ?#!Be aware of sound signals on the River Thames. 5. Once you are within a few meters turn off the motor and pass the front Short: I am altering my course to STARBOARD. -

THE RIVER THAMES a Complete Guide to Boating Holidays on the UK’S Most Famous River the River Thames a COMPLETE GUIDE

THE RIVER THAMES A complete guide to boating holidays on the UK’s most famous river The River Thames A COMPLETE GUIDE And there’s even more! Over 70 pages of inspiration There’s so much to see and do on the Thames, we simply can’t fit everything in to one guide. 6 - 7 Benson or Chertsey? WINING AND DINING So, to discover even more and Which base to choose 56 - 59 Eating out to find further details about the 60 Gastropubs sights and attractions already SO MUCH TO SEE AND DISCOVER 61 - 63 Fine dining featured here, visit us at 8 - 11 Oxford leboat.co.uk/thames 12 - 15 Windsor & Eton THE PRACTICALITIES OF BOATING 16 - 19 Houses & gardens 64 - 65 Our boats 20 - 21 Cliveden 66 - 67 Mooring and marinas 22 - 23 Hampton Court 68 - 69 Locks 24 - 27 Small towns and villages 70 - 71 Our illustrated map – plan your trip 28 - 29 The Runnymede memorials 72 Fuel, water and waste 30 - 33 London 73 Rules and boating etiquette 74 River conditions SOMETHING FOR EVERY INTEREST 34 - 35 Did you know? 36 - 41 Family fun 42 - 43 Birdlife 44 - 45 Parks 46 - 47 Shopping Where memories are made… 48 - 49 Horse racing & horse riding With over 40 years of experience, Le Boat prides itself on the range and 50 - 51 Fishing quality of our boats and the service we provide – it’s what sets us apart The Thames at your fingertips 52 - 53 Golf from the rest and ensures you enjoy a comfortable and hassle free Download our app to explore the 54 - 55 Something for him break. -

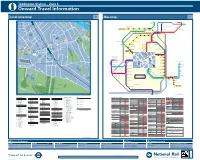

Buses from Teddington

Teddington Station – Zone 6 i Onward Travel Information Local area map Bus mapBuses from Teddington 36 R A 117 20 I L C W 1 R O V E A E G G 95 T H R O V E G A R 19 H Y 45 49 R 30 58 99 88 ELMTREE ROAD U O 481 33 88 Teddington A D River Thames R D 23 ENS West Middlesex 95 Hammersmith 84 Lock C 156 21 23 Bowling University Hospital CLAREMONT ROAD Bus Station 98 149 H Green R68 81 25 T H E G R O V E Kew R 48 147 O Footbridge 1 Retail Park 93 145 4 77 TEDDINGTON PARK ROAD 85 A VICTOR ROAD Maddison TEDDINGTON PARK S E N 80 D Footbridges R 41 86 D Centre 32 A Castelnau G 88 V E 30 141 O G R HOUNSLOW Richmond RICHMOND 1 10 79 C N A Twickenham Teddington LINDEN GROVE M Lower Mortlake Road 57 B Barnes 73 R Hounslow Whitton Whitton Tesco 95 Social Club I E D H A L L C O U R T 24 L G Red Lion E 33 Treaty Centre Church M L Hounslow Admiral Nelson 44 84 12 C M 100 R T 73 E O H 28 R S A C 58 R E O 17 A E T R O A D L D I 116 E B 281 C R Hounslow Twickenham Richmond 56 ELMFIELD AVENUE E 63 44 R S T N 105 27 O I N 29 8 SOMERS 82 T M Twickenham A 7 S O Bus Station Stadium E M A N O R R O A D D BARNES W 59 31 14 61 R Barnes RAILWAY ROAD 28 56 4 13 52 17 TWICKENHAM ROAD R Twickenham 95 D SOMERSET GARDENS B A The HENRY PETERS L O O 106 TEDDINGTON PARKE 77 130 25 N 45 R 4 York Street D H Y Tide End Kneller Road E 50 A R DRIVE CHURCH ROAD I A M 72 R E Cottage O P CAMBRIDGE CRESCENT D F Kneller Hall L 41 R A 32 4 TWICKENHAM Sheen Road East Sheen Barnes Common 41 C S T O K E S M E W S E 4 1 T ST. -

Sequential Assessment Department for Education

SEQUENTIAL ASSESSMENT DEPARTMENT FOR EDUCATION/BOWMER AND KIRKLAND LAND OFF HOSPITAL BRIDGE ROAD, TWICKENHAM, RICHMOND -UPON- THAMES LALA ND SEQUENTIAL ASSESSMENT On behalf of: Department for Education/Bowmer & Kirkland In respect of: Land off Hospital Bridge Road, Twickenham, Richmond-upon-Thames Date: October 2018 Reference: 3157LO Author: PD DPP Planning 66 Porchester Road London W2 6ET Tel: 0207 706 6290 E-mail [email protected] www.dppukltd.com CARDIFF LEEDS LONDON MANCHESTER NEWCASTLE UPON TYNE ESFA/Bowmer & Kirkland Contents 1.0 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................. 4 2.0 QUANTITATIVE NEEDS ANALYSIS ....................................................... 5 3.0 POLICY CONTEXT .............................................................................11 4.0 SEQUENTIAL TEST METHODOLOGY .................................................17 5.0 ASSESSMENT OF SITES .....................................................................22 6.0 LAND OFF HOSPITAL BRIDGE ROAD ................................................55 7.0 CONCLUSION ...................................................................................57 Land at Hospital Bridge Road, Twickenham, Richmond-upon-Thames 3 ESFA/Bowmer & Kirkland 1.0 Introduction 1.1 This Sequential Assessment has been prepared on behalf of the Department for Education (DfE) and Bowmer & Kirkland, in support of a full planning application for a combined 5FE secondary school and sixth form, three court MUGA and associated sports facilities, together with creation of an area of Public Open Space at Land off Hospital Bridge Road, Twickenham, Richmond-upon- Thames (the ‘Site’). Background 1.2 Turing House School is a 5FE 11-18 secondary school and sixth form, which opened in 2015 with a founding year group (Year 7) on a temporary site on Queens Road, Teddington. The school also expanded onto a further temporary site at Clarendon School in Hampton in September 2018, and plans to remain on both of these temporary sites until September 2020. -

TLS REVIEW REPORT SEPTEMBER 2012.Indd

THE RECREATION LANDSCAPE 2.123 2012 Update: This section establishes the main reasons for visiting the Arcadian Thames and summarises the ways that visitors use, move about and understand the river corridor. It celebrates the network of opportunities for recreation and sets out ways to provide a welcoming, connected, legible and accessible landscape. 2.124 Strategic guidance is set out in: • The London Plan The 18th Century river landscape was designed for the pleasure of • The Disability Discrimination Act (DDA) the court • Mayor’s Tourism Plan for South London • The River Thames Alliance Thames Waterway Plan The Arcadian Thames 2.125 2012 Update: The London Plan proposes a series of Strategic Cultural Areas for London. These are designated as those places that help to make London a unique and vibrant city. The Thames corridor between Hampton and Kew has been recognised as one of London’s cultural areas and is referred to as ‘London’s Arcadia’. A Connected Landscape 2.126 2012 Update: The Arcadian Thames was originally laid out for the private enjoyment of the court. It was the cradle of the English Landscape Movement and inspired generations of artists, writers, poets and thinkers. During the 19th century however, this privileged landscape was opened up for the public to enjoy, quickly earning a reputation as the playground for London. Today, the River À ows through a green corridor of parks, palaces, visitor attractions, wildlife sites and historic settlements un-equalled in any During the 19th Century the other European capital city. These spaces form the largest connected Arcadian Thames was opened up for everyone to enjoy area of public open space in the metropolis offering the visitor an amazing combination of different leisure and learning experiences. -

Twickenham Conference

8,)&%6)*338 '327908%8-32 6)79087 8[MGOIRLEQ&EVIJSSX'SRWYPXEXMSR¯.YP] Table of contents INTRODUCTION 3 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 4 SOAP BOX AND VIDEO DIARY THEMES 5 SURVEY QUESTIONNAIRE 8 ARTIST IMPRESSIONS 11 IDEAS WALL 12 ONLINE SURVEY 15 2 Introduction Twickenham is one of the largest town centres in Richmond upon Thames and there are a number of large development opportunities in the area which aim to improve its economic standing and built environment. These opportunities include: the regeneration of the Riverside area, the possible redevelopment of the Post Office Sorting site and planned improvements at Twickenham Station. In addition the soon to open hotel at Regal House will no doubt impact the local economy, parking and employment. With this in mind, and given the new administrations commitment to listen to the views of all residents regarding their local community, Richmond Council has committed to carry out a three-stage consultation involving residents and businesses in Twickenham. The first stage of the consultation – the Barefoot Consultation was an informal event giving all residents and businesses in Twickenham the opportunity to share their ideas about how Twickenham should be developed. This report concentrates on the findings from this event. The event was hosted in the Clarendon Hall and then moved to the Civic Centre Atrium from Thursday 22 – Saturday 24 July. It was made up of several different areas. Exhibition Inviting local residents and community groups to display their ideas and proposals for the local area. Ideas Wall All visitors to the exhibition were invited to write down their ideas and thoughts about Twickenham. -

The Anglers Teddington Lock and Ham House.Pages

A 3.5 mile circular pub walk from The Anglers in Teddington, Middlesex THE ANGLERS, TEDDINGTON LOCK The Anglers is a delightful, family friendly bar, serving up great fare from a peaceful riverside location, making it a AND HAM HOUSE, MIDDLESEX blissful spot for a lingering meal or quick refreshment. The walking route crosses the Thames, before exploring the opposite bank with chance to see famous landmarks including Teddington Lock, Eel Pie Island and Ham House along the way. Easy Terrain Getting there The Anglers is located on Broom Road in Teddington, directly alongside the river by Teddington Lock. You will probably find it easiest to arrive by public transport. 3.5 miles Teddington train station is half a mile up the High Street (from the station go left onto Station Road, then right onto the High Street, go ahead at the lights into Ferry Circular Road and follow this swinging right into Broom Road to find the pub). The area is well connected by bus, there are stops along Ferry Road - you will need the R68, 281 1.5 hours or 285. If you are coming by car, the pub has its own small car park and there is some street parking available (but check local restrictions). 240417 Approximate post code TW11 9NR. Walk Sections Go 1 Start to Teddington Lock Access Notes 1. The route is almost entirely flat, with no gradients to Leave the pub’s front car park onto Broom Road and turn speak of. right along the pavement. Where the road swings left, 2. There are no gates or stiles on route, but you will need turn right towards the river. -

THE NATURAL LANDSCAPE 2.72 the River Thames Is London's Best Known Natural Feature. It Twists and Turns Through London, Changi

THE NATURAL LANDSCAPE 2.72 The River Thames is London’s best known natural feature. It twists and turns through London, changing from a large freshwater river at Hampton into a saline estuary in the east. The river forms a continuous green corridor stretching through London, between the countryside and the sea. 2.73 The nature conservation importance of the linear features of the river channel, mudfl ats and banks cannot be separated from the land in the river corridor. The stretch between Hampton and Kew has Access to the river is particulary the largest expanse of land designated with Site of Special Scientifi c good along the Arcadian Thames Interest status in London. 2.74 For centuries, people have been fascinated by the River Thames, and it continues to attract and inspire local residents and visitors from central London and abroad. Part of the great attraction of the river is the accessible experience of tranquil nature among the concrete and asphalt of the city - the fl ash of a kingfi sher, the bright colour of a wildfl ower or a sudden cloud of butterfl ies have a special resonance in the urban setting. One of the main aims of the Strategy is to ensure the continued balance between wildlife conservation and public access and enjoyment. The Thames is London’s best outdoor classroom 2.75 Over the centuries, the land and the river have been infl uenced by man’s activities. No habitat in London is truly natural which means that we have a particular responsibility to continue to manage the area in ways that conserve a mosaic of attractive habitats and to take special care of rarities. -

The Story of Nursing in British Mental Hospitals

Downloaded by [New York University] at 12:59 29 November 2016 The Story of Nursing in British Mental Hospitals From their beginnings as the asylum attendants of the nineteenth century, mental health nurses have come a long way. This is the first comprehensive history of mental health nursing in Britain in over twenty years, and during this period the landscape has transformed as the large institutions have been replaced by services in the community. McCrae and Nolan examine how the role of mental health nursing has evolved in a social and professional context, brought to life by an abundance of anecdotal accounts. The nine chronologically ordered chapters follow the development from untrained attendants in the pauper lunatic asylums to the professionally qualified nurses of the twentieth century, and, finally, consider the rundown and closure of the mental hospitals from nurses’ perspectives. Throughout, the argument is made that while the training, organisation and environment of mental health nursing has changed, the aim has remained essentially the same: to nurture a therapeutic relationship with people in distress. McCrae and Nolan look forward as well as back, and highlight significant messages for the future of mental health care. For mental health nursing to be meaningfully directed, we must first understand the place from which this field has developed. This scholarly but accessible book is aimed at anyone with an interest in mental health or social history, and will also act as a useful resource for policy- makers, managers and mental health workers. Niall McCrae is a lecturer in mental health nursing at Florence Nightingale Faculty of Nursing & Midwifery, King’s College London. -

Britain in Bloom Submisson

HAM & PETERSHAM IN BLOOM 2018 HAM & PETERSHAM IN BLOOM 2018 CONTENTS Page 4-5 Map of Ham & Petersham 6 Ham and Petersham, recent achievements 7-8 The Bloom Campaign, Groups & Organisations within the Campaign 25 The schools 25 Leisure and recreational facilities 27 The Ham and Petersham Neighbourhood Plan 28 Ham and Petersham Calendar 28 Future Plans and strategy 29 Thanks and sponsors 2 3 Location key: 1. Ham Lands 2. Ham House 3. Ham Polo Ground 4. Walnut Tree Allotment 5. Ham Village Green 6. Library Garden 7. Grey Court School 8. South Avenue 9. Ham Common 10. Ham Gate House Garden 11. Parkleys 12. Ham Common Woods 13. Toad Ponds 14. Latchmere Brook 15. Petersham Meadows 16. Petersham Common Woods 17. The Cassel Hospital 18. Ham Parade 4 5 HAM & PETERSHAM Ham and Petersham is within the Borough of Richmond, bordered on the east by Richmond Park, to the west by the Thames, and to the south by the Royal Borough of Kingston. The village was recorded as Piterichesham in the 1086 Doomsday Book. Ham is not mentioned, but derives its name from the meaning of a meadowland in a river bend or Hamms. Large expanses of parkland and water meadows constrained the growth of Ham and Petersham, preserving their dis- tinctive rural character in the 19th century. The railways never reached these villages and therefore there was no rapid expansion during the Victorian period. The 20th Century brought a number of small housing estates, some houses built in the grounds of the larger properties, and development by Richmond Council of a few roads as part of the plan to reduce the housing list.