Desai 1-10-12.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mineral Blocks for Ruminants in Malaysia 213

cover.eps 26-11-2007 0:33:0:33:1515 164 164 ISSN 0254-6019 FAO ANIMAL PRODUCTION AND HEALTH C Feed SupplementationBlocks M In facing ever more limited resources and changing market conditions and in the attempt Y to enhance productivity for strengthening livelihoods, many technologies have been used CM to improve feed use and animal performance at the farm level. A particularly successful example, in terms of both geographic range of use and relative simplicity in formulation paper MY and preparation, is the urea-molasses multi-nutrient block technology. This publication CY provides a comprehensive overview of development and use of the block technology in CMY countries around the world and it might be of great practical value to extension workers, K students, researchers and those thinking of using such feed supplementation technology or of starting commercial production. FEED SUPPLEMENTATION BLOCKS Urea-molasses multinutrient blocks: simple and effective feed supplement technology for ruminant agriculture ISBN 978-92-5-105438-3 ISSN 0254-6019 978 9 2 5 1 0 5 4 3 8 3 TC/M/A0242E/1/11.07/1000 FAO Cover photographs: Centre: © Michael W. Davidson and Florida State University Right: M. A. S. Khan 164 FAO ANIMAL PRODUCTION AND HEALTH paper FEED SUPPLEMENTATION BLOCKS Urea-molasses multinutrient blocks: simple and effective feed supplement technology for ruminant agriculture Edited by Harinder P.S. Makkar Joint FAO/IAEA Division of Nuclear Techniques in Food and Agriculture and Manuel Sánchez and Andrew W. Speedy Animal Production and Health -

District Census Handbook, 11 Ahmedabad

CENS:US 1961 GUJARAT DISTRICT CENSUS HANDBOOK 11 AHMEDABAD [)ISTRICT R. K. TRIVEDI Superintendent of Census Operations, Gujarat PRICE 'as. 9.45 nP. DISTRICT AHMEDABAD • M~H'ANA - J' .' :" ." ..... : .•. .... , REFERENCES ., DiSTRICT H Q S TALUKA H Q -- D,STRICT BOUNDARY ..•.••.•• TALUKA BOUNDARY :tmm BROAO GAUGE - METER GAUGE .,e= CANAL _RIVER ® RUT HOUSE ® POLICE STATION o LlNI"HAet~!~ • VILLAGE~ • VILLAGe2ooo~ • VILLAGE _ 50._ e TOWN 1!!!!J MUNICIPALITY -=- NATIONAL HIGHWAY = STATE HIGHWAY ---- LOCAL ROAD PO POST OFFICE P T POST • TELEGRAPH CENSUS OF INDIA 1961 LIST OF PUBLICATIONS CENTRAL GOVERNMENT PUBLICATIONS Census of India, 1961 Volume V-Gujarat is being published in the following parts: I-A General Report I-B Report on Vital Statistics and Fertility Survey I-C Subsidiary Tables II-A General Population Tables II-B (1) General Economic Tables (Tables B-1 to B-IV-C) II-B (2) General Economic Tables (Tables B-V to B-IX) I1-C Cultural and Migration Tables III Household Economic Tables (Tables B-X to B-XVII) IV-A Report on Housing and Establishments IV-B Housing and Establislunent Tables V-A Tables on Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes V-B Ethnographic Notes on Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes (including reprints) VI Village Survey Monographs (25 Monographs) VI I-A Selected Crafts of Gujarat VII-B Fairs and Festivals VIIJ-A Administration Report-Enumeration Not for Sa)"'_: VIII-B Administration Report-Tabulation } -~( IX Atlas Volume X Special Report on Cities STATE GOVERNMENT PUBLICATIONS 17 District Census Handbooks i~ English -

State District Branch Address Centre Ifsc Contact1 Contact2 Contact3 Micr Code

STATE DISTRICT BRANCH ADDRESS CENTRE IFSC CONTACT1 CONTACT2 CONTACT3 MICR_CODE ANDAMAN NO 26. MG ROAD AND ABERDEEN BAZAR , NICOBAR PORT BLAIR -744101 704412829 704412829 ISLAND ANDAMAN PORT BLAIR ,A & N ISLANDS PORT BLAIR IBKL0001498 8 7044128298 8 744259002 UPPER GROUND FLOOR, #6-5-83/1, ANIL ANIL NEW BUS STAND KUMAR KUMAR ANDHRA ROAD, BHUKTAPUR, 897889900 ANIL KUMAR 897889900 PRADESH ADILABAD ADILABAD ADILABAD 504001 ADILABAD IBKL0001090 1 8978899001 1 1ST FLOOR, 14- 309,SREERAM ENCLAVE,RAILWAY FEDDER ROADANANTAPURA ANDHRA NANTAPURANDHRA ANANTAPU 08554- PRADESH ANANTAPUR ANANTAPUR PRADESH R IBKL0000208 270244 D.NO.16-376,MARKET STREET,OPPOSITE CHURCH,DHARMAVA RAM- 091 ANDHRA 515671,ANANTAPUR DHARMAVA 949497979 PRADESH ANANTAPUR DHARMAVARAM DISTRICT RAM IBKL0001795 7 515259202 SRINIVASA SRINIVASA IDBI BANK LTD, 10- RAO RAO 43, BESIDE SURESH MYLAPALL SRINIVASA MYLAPALL MEDICALS, RAILWAY I - RAO I - ANDHRA STATION ROAD, +91967670 MYLAPALLI - +91967670 PRADESH ANANTAPUR GUNTAKAL GUNTAKAL - 515801 GUNTAKAL IBKL0001091 6655 +919676706655 6655 18-1-138, M.F.ROAD, AJACENT TO ING VYSYA BANK, HINDUPUR , ANANTAPUR DIST - 994973715 ANDHRA PIN:515 201 9/98497191 PRADESH ANANTAPUR HINDUPUR ANDHRA PRADESH HINDUPUR IBKL0001162 17 515259102 AGRICULTURE MARKET COMMITTEE, ANANTAPUR ROAD, TADIPATRI, 085582264 ANANTAPUR DIST 40 ANDHRA PIN : 515411 /903226789 PRADESH ANANTAPUR TADIPATRI ANDHRA PRADESH TADPATRI IBKL0001163 2 515259402 BUKARAYASUNDARA M MANDAL,NEAR HP GAS FILLING 91 ANDHRA STATION,ANANTHAP ANANTAPU 929710487 PRADESH ANANTAPUR VADIYAMPETA UR -

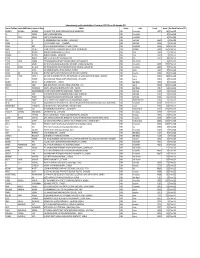

Unpaid Dividend List

Statement showing unpaid/unclaimed dividend of financial year 2015‐2016 as on 18th September,2020. Investor First Name Investor Middile Name Investor Last Name Address Country State Pincode Amount Due Date of Transfer to IEPF SURENDRA MANUBHAI ENGINEER A‐2, BHARAT APPTS., BEHIND TELEPHONE EXCHANGE CHEMBUR NAKA , INDIA Maharashtra 400071 396 27‐Nov‐2023 M R SSINIVAS H NO 7/1/989 SHANKER VEEDHI , , INDIA Maharashtra 39 27‐Nov‐2023 R VIJAYA AMAAJU H NO 7/1/989 SHANKER VEEDHI , , INDIA Maharashtra 39 27‐Nov‐2023 RAJA R 11, KINNIMANGALAM STREET THENKARAI , , PERIYAKULAM INDIA Tamil Nadu 625601 6 27‐Nov‐2023 KUMAR S KS 4/9, KULOTHUNGAN STREET , , , SIVAGANGAI INDIA Tamil Nadu 630561 9 27‐Nov‐2023 SURESH NAIR 21/337 ADARSH NAGAR PRABHADEVI P O WORLI , MUMBAI INDIA Maharashtra 400025 198 27‐Nov‐2023 FRANK COELHO TECHNIC ENTERPRISES LALBAGH FORT ROAD 4/2 4TH CR , DODDAMALAVALI INDIA Karnataka 560004 1560 27‐Nov‐2023 MOHINI DEVI MUNDRA MAIN ROAD RAMBHA GANJAM DIST , ORISSA INDIA Orissa 761028 21 27‐Nov‐2023 NATHMAL MUNDRA MAIN ROAD RAMBHA , , GANJAM DIST INDIA Orissa 761028 9 27‐Nov‐2023 DINESH MONGA H.NO. 163 GALI NO. 8 WEST AZAD NAGAR , DELHI INDIA Delhi 110051 84 27‐Nov‐2023 DEVESH KUMAR SHARMA 176 TARIN BAHADUR GANJ SHREE DHAR SHUKLA MARG , DISTT SAHAJANPUR INDIA Uttar Pradesh 39 27‐Nov‐2023 RUPESH R BADIANI FLAT NO 92 HASSA MAHAL DALAMAL PARK CUFFE PARADE , MUMBAI MAHARASHTRA INDIA Maharashtra 400005 7500 27‐Nov‐2023 SHEELA DEVIDAS MAHAJAN PLOT NO 44B NEAR DR. WAGH'S HOSPITAL RATHI NAGAR VMV ROAD , AMRAVATI MS INDIA Maharashtra 444603 78 27‐Nov‐2023 ROSHNI BHATIA 122, NIRANKARI COLONY AMRITSAR AMRITSAR , AMRITSAR INDIA Punjab 143001 78 27‐Nov‐2023 MANJU DEVI MAHAMIA MAHAMIA HOSPITAL P/O FATEHPUR SHEKHAWATI DIST‐ SIKAR , RAJASTHAN INDIA Rajasthan 332301 315 27‐Nov‐2023 MAHESH RATILAL KOTECHA C/O. -

City Wise List of Linked Local Cable Operators of M/S GTPL Hathway, As Reported to TRAI, on 25.05.2015

City wise List of Linked Local Cable Operators of M/s GTPL Hathway, as reported to TRAI, on 25.05.2015. Name of City S. No Name of State (Area of Name of Linked LCO Address of Linked LCO operation) 1 BIHAR PATNA B.S.V CABLE NETWORK PAHARPUR,POLICE COLONY, ANISABAD, PATNA, BIHAR, 0 2 BIHAR PATNA S.R CABLE NETWORK S/O LATE. SUNDAR PRASAD, SOUTH MANDIRIKATHPULPATNA, REENA VILLA SHANTINIKETAN, PATNA, PATNA, BIHAR, 800001 3 BIHAR PATNA ANIKIT VISION DHANOOTRUPASPURPATNA, PATNA, REENA VILLA SHANTINIKETAN, PATNA, PATNA, BIHAR, 801506 4 BIHAR PATNA VINOD CABLE NETWORK S/O LAXMI MAHTONIKASH PIND, PATNACITYREENA VILLA SHANTINIKETAN, PATNA, PATNA, PATNA, BIHAR, 800008 5 BIHAR PATNA ANMOL NAMAN CABLE NETWORK S/O LT.BRIJNANDAN PRASAD YADAVLODIPURKESHAVLAALROAD, , REENA VILLA SHANTINIKETAN, PATNA, PATNA, BIHAR, 800001 6 BIHAR PATNA N‐BUDDHA CABLE NETWORK DUJRA PURBI GALIBUDDHA COLONYPATNA, , REENA VILLA SHANTINIKETAN, PATNA, PATNA, BIHAR, 800001 7 BIHAR PATNA RANJAN ENTERPRISES DR.JANARDHAN GALINEAR PURANDAPUR JAKANPUR, , REENA VILLA SHANTINIKETAN, PATNA, PATNA, BIHAR, 800001 8 BIHAR PATNA M/S MADAN CABLE NETWORK PATNA NAGAR NIGAMSHEK BUCHER KA CHAURAHA, DURGA CHARAN LANE NEAR SHIV MANDIRP.O GULZARBAGH, PS‐ ALAM GUNJ PATNA, PATNA, PATNA, BIHAR, 800007 9 BIHAR PATNA MAA MANGLA GAURI CABLE LAXMI NIWAS KADAM KUAN CHORI MARKET, , REENA VILLA NETWORK SHANTINIKETAN, PATNA, PATNA, BIHAR, 800003 10 BIHAR PATNA ENTERTAINMENT CITY CABLE N/W DAHUA CHAK NAGLA, MALSALAMI, PATNA, PATNA, PATNA, (RC BIHAR, 800008 11 BIHAR PATNA SONY MANORANJAN NETWORK BHAISANI TOLA, MALSALAMI, PATNA, PATNA, PATNA, BIHAR, (RC) 800008 12 BIHAR PATNA PAWAN CABLE NETWORK(JMD) BADI NAGLA, MALSALAMIPATNA CITY, PATNA, PATNA, PATNA, BIHAR, 800008 City wise List of Linked Local Cable Operators of M/s GTPL Hathway, as reported to TRAI, on 25.05.2015. -

GROUND WATER LEVEL SCENARIO in RAJASTHAN - 2014 Pre and Post Monsoon Survey - 2014

Government of Rajasthan Ground Water Department GROUND WATER LEVEL SCENARIO IN RAJASTHAN - 2014 Pre and Post Monsoon survey - 2014 DATA STORAGE AND PROCESSING CELL (DSPC) APRIL, 2015 CONTENTS Page. No. 1.0 Overview 1 – 3 1.1 Climate 1 1.2 Rainfall 1 1.3 Physiography 1 1.4 Drainage 2 1.5 Hydrogeology 2 2.0 Abstract 4 3.0 Scenario Of Groundwater Level In Rajasthan – Year 2014 5 – 9 3.1 Depth to water level Pre Monsoon – 2014 5 3.2 Depth to water level Post Monsoon – 2014 6 – 7 Change In Water Level (Fluctuation) Pre Monsoon - 2014 To 3.3 8 – 9 Pre Monsoon – 2014 4.0 Rainfall condition – 2014 10 FIGURES 1 Aquifer Distribution Map of Rajasthan as per ROLTA Study. 11 PLATES District Wise Average Depth To Water Level Of Pre Monsoon 1.1 to 1.3 12 – 14 2014 And Post Monsoon – 2014 2 Change in water level pre monsoon & post monsoon – 2014 15 3.1 to 3.2 Rainfall condition of all the districts during 2013 & 2014 16 – 17 TABLES District Wise Average Depth To Water Level During Pre 1 18 Monsoon and Post Monsoon 2014 Block Wise Average Depth To Water Level And Fluctuation 2 19 – 25 During Pre Monsoon 2014 And Post Monsoon 2014 Depth To Water Level Data Of Key Wells During Pre 3 26 – 148 Monsoon and Post Monsoon – 2014 Normal Monsoon, Non monsoon, Annual Rainfall & Rainfall 4 149 Condition 2014 1.0 OVERVIEW Rajasthan, the largest state of India with geographical area of 342230 Sq.km. and situated in the north-western part of the country. -

Demonstration Packet

Understanding solutions to prevent heat stress in cities. DEMONSTRATION PACKET CITY HEAT RESILIENCE TOOLKIT FOR SURAT CITY APRIL 2021 The report is developed with the support of Climate and Development Knowledge Network through the Knowledge Brokering Program. The report is developed through the understanding, literature review and analysis by the technical team and inputs from the contributors as well as experts. Disclaimers The content of this document does not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of Taru Leading Edge or Urban Health and Climate Resilience Centre for Excellence or SahaMantharan Pvt. Ltd. on the legal status, boundary, authorities or delimitation of any city or country. Mention of any commercial company, guideline or product does not imply any endorsement by Taru Leading Edge. Trademark names and icons from the program are used in an editorial fashion with no intention on infringement of trademark or copyright laws. The views expressed in this document are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of respective organizations. We regret any errors or omissions that may have been unwillingly made. NO.02 APRIL 2021 DEMONSTRATION PACKET Climate and Development Urban Health and Climate Knowledge Network (CDKN) Resilience Centre The Climate and Development Knowledge Urban Health and Climate Resilience Center Network (CDKN) is a programme funded by the (UHCRC), is a health and climate change initiative Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Netherlands and in Surat city by the Asian Cities Climate Change the International Development Research Centre Resilience Network (ACCCRN) and supported (IDRC), Canada working towards enhancing the by Rockefeller Foundation through the Surat quality of life for the poorest and most vulnerable City Climate Trust, in which the Surat Municipal to climate change, by supporting decision-makers Corporation is the main stakeholder. -

First Name Middle Name Last Name Address Country State

Biocon Limited Amount of unclimed and unpaid Interim dividend for FY 2010-11 First Name Middle Name Last Name Address Country State District PINCode Folio Number of Amount Proposed Securities Due(in Date of Rs.) transfer to IEPF (DD- MON-YYYY) JAGDISH DAS SHAH HUF CK 19/17 CHOWK VARANASI INDIA UTTAR PRADESH VARANASI BIO040743 150.00 03-JUN-2018 RADHESHYAM JUJU 8 A RATAN MAHAL APTS GHOD DOD ROAD SURAT INDIA GUJARAT SURAT 395001 BIO054721 150.00 03-JUN-2018 DAMAYANTI BHARAT BHATIA BNP PARIBASIAS OPERATIONS AKRUTI SOFTECH PARK ROAD INDIA MAHARASHTRA MUMBAI 400093 BIO001163 150.00 03-JUN-2018 NO 21 C CROSS ROAD MIDC ANDHERI E MUMBAI JYOTI SINGHANIA CO G.SUBRAHMANYAM, HEAD CAP MAR SER IDBI BANK LTD, INDIA MAHARASHTRA MUMBAI 400093 BIO011395 150.00 03-JUN-2018 ELEMACH BLDG PLOT 82.83 ROAD 7 STREET NO 15 MIDC, ANDHERI EAST, MUMBAI GOKUL MANOJ SEKSARIA IDBI LTD HEAD CAPITAL MARKET SERVIC CPU PLOT NO82/83 INDIA MAHARASHTRA MUMBAI 400093 BIO017966 150.00 03-JUN-2018 ROAD NO 7 STREET NO 15 OPP SPECIALITY RANBAXY LABORATORI ES MIDC ANDHERI (E) MUMBAI-4000093 DILIP P SHAH IDBI BANK, C.O. G.SUBRAHMANYAM HEAD CAP MARK SERV INDIA MAHARASHTRA MUMBAI 400093 BIO022473 150.00 03-JUN-2018 PLOT 82/83 ROAD 7 STREET NO 15 MIDC, ANDHERI.EAST, MUMBAI SURAKA IDBI BANK LTD C/O G SUBRAMANYAM HEAD CAPITAL MKT SER INDIA MAHARASHTRA MUMBAI 400093 BIO043568 150.00 03-JUN-2018 C P U PLOT NO 82/83 ROAD NO 7 ST NO 15 OPP RAMBAXY LAB ANDHERI MUMBAI (E) RAMANUJ MISHRA IDBI BANK LTD C/O G SUBRAHMANYAM HEAD CAP MARK SERV INDIA MAHARASHTRA MUMBAI 400093 BIO047663 150.00 03-JUN-2018 -

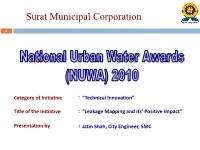

Surat Municipal Corporation

Surat Municipal Corporation 1 Category of Initiative : “Technical Innovation” Title of the Initiative : “Leakage Mapping and its’ Positive Impact” Presentation by : Jatin Shah, City Engineer, SMC Location: Surat City TO KATHOR Surat City Variav TO AHMEDABAD Kosad TO OLPAD Mota TO KATHOR G.H.B 3 Varachha Kosad E G.H.B V I G.H.B R Jahangirpura I Chhapra P Bhatha TO HAZIRA 28 A T TO KAMREJ Ved TO DANDI Pisad Amroli Sarthana GAMTAL G.E.B. Power House GAMTAL Utran E 53 V Utran 69 I Dabholi Katargam R I Nanavarachha G.I.D.C. P 76 K a t a r g a m A Jahangirabad T 30 51 NORTH ZONE31 29 Rander Singanpor 129 71 70 D.T.P.S. NO - 20 D.T.P.S. NO - 20 (Nana V arach ha-Kapadra) 50 WEIR CUM CAUSE WAY T.P.S.NO.18 (Katargam) T.P.S.-15 Simada TO BHESAN (Fulpada) T.P.S.NO.1 4 T.P.S.NO.3 (Rander Adajan) (Katargam) Fulpada T.P.S. NO 16 59 T.P.S.NO.4 D.T.P.S.NO.17 (Kapa dra ) Ashwanikumar Navagam (Fulpada) Palanpor Tunki D.T .P.S. NO.24 19 D.T.P.S. NO.23 T.P.S.NO.13 45 (Rander) (Adajan) T.P.S.NO .1 (Lal Darwa ja)) 172 T.P.S.NO.11 7 72 (Adajan) EAST ZONE 33 T.P.S.NO.3 1 (Karanj) WEST ZONE 12 62 Puna 14 35 18 57 EXIST.NEHRU BRIDGE T.P.S.NO.12 13 (Adajan) 41 40 SWAMI VIVEKANAND BRIDGE 61 37 60 T.P.S.NO.8 10 (Umarwada ) Magob LOW LEVEL BRIDGE 15 11 TO HAZIRA 77 Adajan 75 21 43 34 17 T.P.S. -

Study of the Strategies Adopted by Surat Municipal Corporation and Its Effects on the Quality of Public Life

STUDY OF THE STRATEGIES ADOPTED BY SURAT MUNICIPAL CORPORATION AND ITS EFFECTS ON THE QUALITY OF PUBLIC LIFE A Thesis submitted to TILAK MAHARASHTRA VIDYAPEETH, PUNE For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Ph.D.) In Management Under the Board of Management Studies Submitted By NETHALA MOHANA RAO PRN NO-15815003766 Under the Guidance of Dr. SURESH ABHYANKAR Department of Management JULY -2018 Tilak Maharashtra Vidyapeeth, Pune Undertaking I, NETHALA MOHANA RAO is the Ph. D Scholar of the Tilak Maharashtra Vidyapeeth in MANAGEMENT Subject. Thesis entitled STUDY OF THE STRATEGIES ADOPTED BY SURAT MUNICIPAL CORPORATION AND ITS EFFECTS ON THE QUALITY OF PUBLIC LIFE under the supervision of Dr. SURESH ABHYANKAR., Solemnly affirm that the thesis submitted by me is my own work. I have not copied it from any source. I have gone through extensive review of literature of the related published / unpublished research works and the use of such references made has been acknowledged in my thesis. The title and the content of research is original. I understand that, in case of any complaint especially plagiarism, regarding my Ph.D. research from any party, I have to go through the enquiry procedure as decided by the Vidyapeeth at any point of time. I understand that, if my Ph.D. thesis (or part of it) is found duplicate at any point of time, my research degree will be withdrawn and in such circumstances, I will be solely responsible and liable for any consequences arises thereby. I will not hold the TMV, Pune responsible and liable in any case. -

RHIHLIP21371V022021.Pdf

Policy Terms and Conditions Please check whether the details given by you about the insured 1.8 AYUSH Day Care Centre means and includes persons in the proposal form (a copy of which was provided at the Community Health Centre (CHC), Primary Health time of issuance of cover for the first time) are incorporated Centre (PHC), Dispensary, Clinic, Polyclinic or any such correctly in the policy schedule. If you find any discrepancy, centre which is registered with the local authorities, please inform us within 15 days from the date of receipt of the wherever applicable, and having facilities for carrying policy, failing which the details relating to the person/s covered out treatment procedures and medical or surgical/para- would be taken as correct. surgical interventions or both under the supervision of registered AYUSH Medical Practitioner (s) on day care So also the coverage details may also be gone through and in the basis without in-patient services and must comply with absence of any communication from you within 15 days from the all the following criterion: date of receipt of the policy, it would be construed that the policy issued is correct and the claims if any arise under the policy will be a. Having qualified registered AYUSH Medical dealt with based on proposal /policy details. Practitioner(s) in charge; For the purposes of interpretation and understanding of the product b. Having dedicated AYUSH therapy sections as the Company has defined, herein below some of the important required and/or has equipped operation theatre words used in the product and for the remaining language and the where surgical procedures are to be carried out; words the Company believes to mean the normal meaning of the c. -

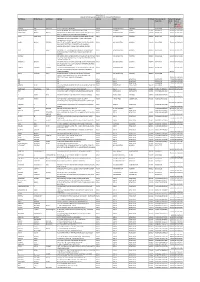

State District Branch Address Centre Ifsc Contact1 Contact2 Contact3 Micr Code

STATE DISTRICT BRANCH ADDRESS CENTRE IFSC CONTACT1 CONTACT2 CONTACT3 MICR_CODE B S PATEL CHEMBERS,OPP KAL;UPUR BANK, NAL SAROVAR TRAN RASTA, AHEMDABAD VIRAMGAM HIGHWAY, SANAND , DIST AHEMDABAD 02717- GUJARAT AHMADABAD SANAND BR 382 110 SANAND PMEC0102826 222131 380234251 RAVISH COMPLEX, ABOVE SALES INDIA, MANI NAGAR CHARRASTA, AHEMDABAD, DIST AHMEDABA 079- GUJARAT AHMEDABAD MANINAGAR BR AHEMDABAD 380008 D PMEC0103128 25462414 079-25462415 1ST FLOOR, F,4-5, NARMADA ARCADE, ANKLESHWAR N H NO. 8, GIDC, ANKLESHW 02646- GUJARAT BHARUCH BR ANKLESHWAR AR PMEC0103431 222585 02646-222586 393250051 SHETHNA PLAZA, NR PANCH BATTI, BHARUCH, DIST 02642- GUJARAT BHARUCH BHARUCH BR BHARUCH BHARUCH PMEC0100809 222583 02642-222584 392250001 1ST FLOOR, AKSHAR MOTEL BUILDING , OPP S T DEPOT, SANTRAM ROAD, 0268- GUJARAT KHEDA NADIAD BR NADIAD, DIST KHEDA NADIAD PMEC0102323 2551962 0268-2551963 NISHCHAY COMPLEX, COLLAGE ROAD, GOHAR BAUGH, BILIMORA, 02634- GUJARAT NAVSARI BILIMORA BR DIST NAVSARI BILIMORA PMEC0101313 289925 396250091 DHAN COMPLEX , MADHUMATI, OPP CENTRAL BANK OF 02637- GUJARAT NAVSARI NAVSARI BR INDIA, NAVSARI NAVSARI PMEC0100708 232763 02637-232764 396250061 SATHARIYA BAZAR, GODHRA, DIST PANCH PANCHMAHAL , 389 02672- GUJARAT MAHALS GODHRA BR 001 GODHRA PMEC0102927 243204 389250001 NEAR OLD BUS 02779- GUJARAT SABAR KANTHA BAYAD STAND BAYAD BAYAD PMEC0103633 222069 383250111 "PLETINUM" STATION ROAD, BARDOLI, 02622- GUJARAT SURAT BARDOLI BR DIST SURAT BARDOLI PMEC0101111 226810 02622-229707 394250051 N=23 TO 26 ASHIRWAD COMPLEX, OPP UMA BHAVAN , BHATAR 0261- GUJARAT SURAT BHATAR BR ROAD, SURAT SURAT PMEC0100607 2237242 0261-2230899 395250007 NANDANVAN COMPLEX, ANAND MAHAL ROAD, BHULKA ADAJAN, SURAT 0261- GUJARAT SURAT BHAVAN BR 395009 SURAT PMEC0100203 2789891 0261-2792533 395250003 101, SHIV POOJA COMPLEX, CITY 0261- GUJARAT SURAT CITY LIGHT BR LIGHT ROAD, SURAT SURAT PMEC0101212 2254106 0261-2252168 395250008 CONTROL CENTER ][ADMINITRATIVE OFFICE] 3RD FLOOR, "TAPI VILLA", VIJAY NAGAR SOCIETY , CONTROL GATE NO.