Buried Dreams

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

22.5. Derby Pages 1-11.2003

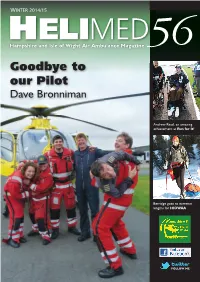

WINTER 2014/15 HELIMED 56 Hampshire and Isle of Wight Air Ambulance Magazine Goodbye to our Pilot Dave Bronniman Andrew Read , an amazing achievement at Run for It! Berridge goes to extreme lengths for HIOWAA FOLLOW ME Welcome to the Winter Contents issue of HELI MED 56 Welcome from Alex Lochrane 1 Patient Story - Ben Coward 2 What an exciting time to be joining such a fantastic charity! Love your Air Ambulance 3 David Berridge 4- 5 The week I joined HIOWAA, everywhere I turned I either read Re-Use-Ya Shoes Day 6- 7 or heard about the news that we will be upgrading to a new Readers’ Photos 8 helicopter to start night flying next year. Getting to know us – 9 Alex Lochrane Patient Story - Sheila Darby 10 From being able to attend road traffic determined, seasoned leadership. I know Ladies Wot Swim 11 collisions in the evening rush hour on many will miss him, but I hope we have Run For It! 12- 13 winter nights, to medical incidents after not seen the last of him. On behalf of you Winter Events 13 the hours of darkness, this expansion of all, I thank him profoundly and wish him Dave Bronniman 14 our service is a huge step forward for us. and Marilyn a very happy retirement Flight for Life 15 None of it could have happened without honing their golf handicap! Sue Tull - Challenges 16- 17 your continued generosity and I feel truly Knight Frank 18 privileged to be working for a charity that We have ambitious plans for Sailing Regatta 19 has such strong support from the the years ahead and our costs Minutes Matter 19 community that it serves. -

8Afdf78ac1020455f3b3db3d584

1 2 SUMMARY 4K p.05 CURRENT AFFAIRS & INVESTIGATION p.08 FOOD INDUSTRY p.13 SCIENCE & KNOWLEDGE p.16 ARCHAEOLOGY & HISTORY p.23 SOCIAL ISSUES & HUMAN INTEREST p.35 WILDLIFE p.41 NATURE & ENVIRONMENT p.46 TRAVEL & DISCOVERY p.52 BIOGRAPHY p.63 DOCU DRAMA & EDUCATIONAL p.65 DOCU SOAP p.67 LIFESTYLE p.69 FILLERS & AERIAL VIEW p.72 PEOPLE & PLACES: AROUND THE SEA p.78 3 4 5 Ultra HD programs LENGTH: 4x52’ MOO! THE EPIC HORNS Meuh ! Les grands bovidés DIRECTOR: Xavier Lefebvre At the dawn of time, their hoof prints mingle with those of Humans. PRODUCER: Step after step, century after century, the great bovine family has Grand Angle Productions accompanied humankind. As essential partners on our greatest ter- COPRODUCERS: ritorial conquests, they continue to change the world at our side even ARTE, TV5 Monde, RSI, today. Ushuaia COPYRIGHT: In the beginning, 18 million years ago, there lived a tiny, shy, forest- 2020 dwelling horned mammal. All alone, through the laws of evolution, LANGUAGE this small antelope becomes the ancestor of the Aurochs, now ex- VERSION AVAILABLE: tinct, which turned humans from the status of hunter-gatherers to French, English that of breeders. Then the ox, yak, buffalo and zebu followed. These descendants are now pivotal elements in many cultures across the world. And against a background of species disappearing from the Earth, they are becoming the biggest land mammals. From their wild forms to the multiple domestic breeds they produced, via the selective hand of humans, the bovines have thus gone side by side with our civilizations throughout our History. -

Download Full Book

Staging Governance O'Quinn, Daniel Published by Johns Hopkins University Press O'Quinn, Daniel. Staging Governance: Theatrical Imperialism in London, 1770–1800. Johns Hopkins University Press, 2005. Project MUSE. doi:10.1353/book.60320. https://muse.jhu.edu/. For additional information about this book https://muse.jhu.edu/book/60320 [ Access provided at 30 Sep 2021 18:04 GMT with no institutional affiliation ] This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Staging Governance This page intentionally left blank Staging Governance theatrical imperialism in london, 1770–1800 Daniel O’Quinn the johns hopkins university press Baltimore This book was brought to publication with the generous assistance of the Karl and Edith Pribram Endowment. © 2005 the johns hopkins university press All rights reserved. Published 2005 Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper 987654321 The Johns Hopkins University Press 2715 North Charles Street Baltimore, Maryland 21218-4363 www.press.jhu.edu Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data O’Quinn, Daniel, 1962– Staging governance : theatrical imperialism in London, 1770–1800 / Daniel O’Quinn. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-8018-7961-2 (hardcover : acid-free paper) 1. English drama—18th century—History and criticism. 2. Imperialism in literature. 3. Politics and literature—Great Britain—History—18th century. 4. Theater—England— London—History—18th century. 5. Political plays, English—History and criticism. 6. Theater—Political aspects—England—London. 7. Colonies in literature. I. Title. PR719.I45O59 2005 822′.609358—dc22 2004026032 A catalog record for this book is available from the British Library. -

THE LAST SPIKE IS DRIVEN! the PACIFIC RAILROAD IS COMPLETED! II the POINT of JUNCTION IS 1,086 MILES WEST of the MISSOURI RIVER, and 690 EAST of Vi SACRAMENTO CITY

ATIONAL GOLDEN SPIKE CENTENNIAL COMMISSION OFFICIAL PUBLICATION MBPPP GOLDEN SP KE CENTENNIAL CELEBRATION COMMISSION "What is past is prologue. ..." Shakespeare's words epitomize the spirit of the nation's railroads as they look to the challenges of the future while celebrating the centennial of an achievement that still stands as one of the great milestones in American history. That event was the completion of the first transcontinental railway system with the Driving of the Golden Spike at Promontory, Utah, on May 10, 1869. It was hailed at the time as an impossible dream come true. And, indeed, it was. Its significance was summarized by the late President John F. Kennedy when he said: "We need not read deeply into the history of the United States to become aware of the great and vital role which the railroads have played in the opening up and developing of this great nation. As our frontier moved westward, it was the railroads that bore the great tide of America to areas of new opportunities and new hopes." The railroad industry is justly proud of its past and its contribution to the growth, development and economic might of America. But, again, what's past is prologue. Railroadmen see vast changes occurring in their industry. Today — a hundred years from Promontory — the Iron Horse has lost most of his passen ger train glamour. But he's still the workhorse of the transportation stable, hauling almost as much freight as all the newer modes combined. New all-time freight records in 1968 are a significant keynote to the future in railroading. -

The Palaeontology Newsletter

The Palaeontology Newsletter Contents 89 Editorial 2 Association Business 3 Association Meetings 28 Palaeontology at EGU 33 News 34 From our correspondents Legends of Rock: Murchison 43 Behind the scenes at the Museum 46 Buffon’s Gang 51 R: Regression 58 PalAss press releases 68 Blaschka glass models 69 Sourcing the Ring Master 73 Underwhelming fossil of the month 75 Future meetings of other bodies 80 Meeting Reports 87 Obituaries Percy Milton Butler 100 Lennart Jeppsson 103 Grant and Bursary reports 106 Book Reviews 116 Careering off course! 121 Palaeontology vol 58 parts 3 & 4 123–124 Papers in Palaeontology, vol 1, part 1 125 Reminder: The deadline for copy for Issue no 90 is 12th October 2015. On the Web: <http://www.palass.org/> ISSN: 0954-9900 Newsletter 89 2 Editorial Here in London summer is under way, although it is difficult to tell just by looking out of the window; once you step outside, however, the high pollen counts are the main giveaway. It is largely the sort of ‘summer’ weather that confuses foreign tourists, makes a mud bath out of music festivals and stops play at Wimbledon. The perfect sort of weather to leave Britain behind and jet off to sunnier climes for a nice long field campaign: as I wistfully gaze at the grey skies I wish I were packing my notebook and field gear ready for departure. Those of you who are setting out for fieldwork during this Northern Hemisphere summer will probably be aware that it is not a walk in the park, as my initial rose-tinted memories lead me to believe. -

On Writing : a Memoir of the Craft / by Stephen King

l l SCRIBNER 1230 Avenue of the Americas New York, NY 10020 Visit us on the World Wide Web http://www.SimonSays.com Copyright © 2000 by Stephen King All rights reserved, including the right of reproduction in whole or in part in any form. SCRIBNER and design are trademarks of Macmillan Library Reference USA, Inc., used under license by Simon & Schuster, the publisher of this work. DESIGNED BY ERICH HOBBING Set in Garamond No. 3 Library of Congress Publication data is available King, Stephen, 1947– On writing : a memoir of the craft / by Stephen King. p. cm. 1. King, Stephen, 1947– 2. Authors, American—20th century—Biography. 3. King, Stephen, 1947—Authorship. 4. Horror tales—Authorship. 5. Authorship. I. Title. PS3561.I483 Z475 2000 813'.54—dc21 00-030105 [B] ISBN 0-7432-1153-7 Author’s Note Unless otherwise attributed, all prose examples, both good and evil, were composed by the author. Permissions There Is a Mountain words and music by Donovan Leitch. Copyright © 1967 by Donovan (Music) Ltd. Administered by Peer International Corporation. Copyright renewed. International copyright secured. Used by permission. All rights reserved. Granpa Was a Carpenter by John Prine © Walden Music, Inc. (ASCAP). All rights administered by WB Music Corp. All rights reserved. Used by permission. Warner Bros. Publications U.S. Inc., Miami, FL 33014. Honesty’s the best policy. —Miguel de Cervantes Liars prosper. —Anonymous First Foreword In the early nineties (it might have been 1992, but it’s hard to remember when you’re having a good time) I joined a rock- and-roll band composed mostly of writers. -

August 8Th - August 21St, 2003

2 - the reykjavík grapevine - august 8th - august 21st, 2003 THE VIEW FROM THE INSIDE YEARNING TO BREATHE FREE THE PLIGHT OF 6 IMMIGRANTS IN ICELAND ICELAND AND THE OUTSIDE WORLD FLIRTING OR A FULL 8 TIME RELATIONSHIP? GAY PRIDE 10 AS MUCH FUN AS IT SOUNDS THE MAIN EVENT CULTURE NIGHT: WHAT´S GOING ON? 14 LETTERS: WHALES, GENETISTS, SPORTS: HOW TO PICK YOUR 4 GERMANS AND THE KKK 20 FAVORITE LOCAL FOOTBALL TEAM EDITORIAL: MONDAY MORNING EVENT: TEDDI, CARVING 5 COMING DOWN, THE TOURIST 21 OUT THE TRUTH FOOD: WHAT´S IT LIKE BEFORE IT NIGHTLIFE: BOOKS VS. BEER. A 12 COMES TO THE SUPERMARKET? 22 FOREGONE CONCLUSION? T3: HE´S BACK (JUST HAD TO SAY FROM THE UNDERGROUND: WILL 13 THAT), CINEMA LISTINGS 23 THE FREE THINKERS BE HEARD? MAP PUBS, COFFEE SHOPS AND ART: THE SIGURJÓN ÓLAFSSON 16 FOOD: ALL YOU NEED TO KNOW 24 MUSEUM INTERVIEW: BEHIND THE EYES OF JUSTICE: ARE ICELAND´S LEADERS 19 THE ICELANDIC LOVE CORPORATION 26 WAR CRIMINALS? THE REYKJAVíK GRAPEVINE ISSUE FIVE, AUGUST 8TH - AUGUST 21ST 2003 Publisher: Hilmar Steinn Grétarsson Editor: Valur Gunnarsson Co-Editors: Jón Trausti Sigurðarson & John Boyce Production director & listings editor: Oddur Óskar Kjartansson Graphic design & Layout: Hörður Kristbjörnsson, ([email protected]) Advertising Directors: Jón Trausti & Hilmar Steinn Photographer: Aldís Pálsdóttir Proof reading: John Boyce & Ingunn Snædal Cover by: Aldís On cover: The Icelandic Love Corporation The Reykjavík Grapevine Printed by: Prentsmiðja Morgunblaðsins Blómvallagötu 2 101 Reykjavík # of Copies: 25.000 Phone numbers: We are always looking for new material. Be warned, however, that it Publisher: 898-9249 is the fi rm policy of the editor not to pay people for their work. -

Selecttv-City Layout 1

Changing the Conversation About Mental Health 1.5 x 2.5” ad Sullivan A Publication of The Chronicle Journal September 18 - 24, 2021 ‘The Wonder Years’ returns, For more information or to order, contact: but with a new cast and place WAKEFIELD OIL CHANGE www.wakefieldoilcheck.com Elisha “EJ” Williams stars in a new version of Phone: 807-345-1121 3 x 5” ad “The Wonder Years” premiering Wednesday on CTV and ABC. Wakefield Oil City BY JAY BOBBIN SelectTV® Published every Saturday by The Chronicle-Journal New characters live At 75 South Cumberland Street, Thunder Bay Ont. P7B 1A3 Hilda Caverly, Interim General Manager, Director of Finance and Circulation ‘The Wonder Years’ in reboot Phone 343-6200 or Toll-free 1-800-465-3914 CHANNEL GUIDE Broadcast Q r Cable Qr Bell ExpressVu/Star Choice 49/49 ^ 210/37 CBLT - CBC Toronto H 509/504 CNBC , # 90/707 CBLFT - CBC French/Toronto I 508/502 CNN Headline News ^ % 223/304 CKPR - CTV/Thunder Bay -/- Broadcast News $ & 222/314 CHFD - Thunder Bay K 618/524 DTOUR _ -/- KSTP - ABC/Minneapolis L 554/544 Teletoon ) ( 265/353 TV Ontario M 556/540 Family Channel ) 400/424 TSN - The Sports Network N 294/529 WPCH - Ind./Atlanta * -/- Shaw Cable TV O 625/548 The Comedy Network + -/- WCCO - CBS/Minneapolis P 292/539 Turner Classic Movies , -/- KTCA - PBS/Minneapolis Q 603/561 The Food Network - -/- KARE - NBC/Minneapolis R 411/457 Outdoor Life . 570/580 Much Music S 522/506 History Television / 501/391 CTV NEWSNET T 627/528 Space A new version of “The 0 502/390 CBC Newsworld U 293/609 AMC Wonder Years” premieres Wednesday on CTV and ABC. -

White Discipline, Black Rebellion: a History of American Race Riots from Emancipation to the War on Drugs

University of New Hampshire University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository Doctoral Dissertations Student Scholarship Winter 2020 White Discipline, Black Rebellion: A History of American Race Riots from Emancipation to the War on Drugs Jordan C. Burke University of New Hampshire, Durham Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.unh.edu/dissertation Recommended Citation Burke, Jordan C., "White Discipline, Black Rebellion: A History of American Race Riots from Emancipation to the War on Drugs" (2020). Doctoral Dissertations. 2544. https://scholars.unh.edu/dissertation/2544 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. White Discipline, Black Rebellion: A History of American Race Riots from Emancipation to the War on Drugs By Jordan C. Burke BA, English, La Salle University, 2004 MA, English, Rutgers University, 2009 MA, Sociology, University of New Hampshire, 2017 PhD, Sociology, University of New Hampshire, 2020 DISSERTATION Submitted to the University of New Hampshire in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Sociology December, 2020 i DISSERTATION COMMITTEE This dissertation was examined and approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Ph.D. in Sociology by: Dissertation Director, Dr. Cliff Brown, Associate Professor of Sociology Dr. Michele Dillon, Dean, College of Liberal Arts and Class of 1944 Professor of Sociology Dr. Cesar Rebellon, Professor of Sociology Dr. -

The Paul Finebaum Show”: Sport Media And

ANALYZING “THE PAUL FINEBAUM SHOW”: SPORT MEDIA AND REPRESENTATIONS OF THE AMERICAN SOUTH ________________________________________________________________________ A Thesis Presented to the faculty of the Graduate School at the University of Missouri – Columbia In Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science by JERETT RION Dr. Grace Yan, Thesis Chair JULY 2016 The undersigned, appointed by the dean of the Graduate School, have examined the thesis entitled ANALYZING “THE PAUL FINEBAUM SHOW”: SPORT MEDIA AND REPRESENTATIONS OF THE AMERICAN SOUTH presented by Jerett Rion, a candidate for the degree of Master of Science, and hereby certify that, in their opinion, it is worthy of acceptance. _______________________________________________________________ Thesis Chair, Dr. Grace Yan ________________________________________________________________ Assistant Teaching Professor, Dr. Nicholas Watanabe ________________________________________________________________ Associate Professor, Dr. Cynthia Frisby ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank all of my committee members for their time and efforts on this project, specifically Dr. Grace Yan. It was her tireless and constant effort of editing my writing and teaching me important philosophies that were fundamental in this research. Without these faculty members, this research would not be near the body of work that stands today. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ............................................................................................... ii ABSTRACT ..................................................................................................................... -

Adventuring with Books: a Booklist for Pre-K-Grade 6. NCTE Bibliography

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 362 878 CS 214 064 AUTHOR Jensen, Julie M., Ed.; Roser, Nancy L,, Ed. TITLE Adventuring with Books: A Booklist for Pre-K-Grade 6. Tenth Edition. NCTE Bibliography Series. INSTITUTION National Council of Teachers of English, Urbana, REPORT NO ISBN-0-8141-0079-1; ISSN-1051-4740 PUB DATE 93 NOTE 682p.; For the previous edition, see ED 311 453. AVAILABLE FROMNational Council of Teachers of English, 1111 W. Kenyon Rd., Urbana, IL 61801-1096 (Stock No. 00791-0015; $14.95 members, $19.95 nonmembers). PUB TYPE Reference Materials - Bibliographies (131) -- Books (010) EDRS PRICE MF04/PC28 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Annotated Bibliographies; *Childrens Literature; Elementary Education; Fantasy; Fiction; Mathematical Concepts; Nonfiction; Poetry; Preschool Education; *Reading Material Selection; *Recreational Reading; Scientific Concepts; Social Studies IDENTIFIERS Eastorical Fiction; Trade Books ABSTRACT Designed to help teachers, librarians, arid parents introduce books of exceptional literary and artistic merit, accuracy, and appeal to preschool through sixth grade children, this annotated bibliography presents nearly 1,800 annotations of approximately 2,000 books (2 or more books in a series appear in a single review) published between 1988 and 1992. Annotations are grouped under 13 headings: Biography; Books for Young Children; Celebrations; Classics; Contemporary Realistic Fiction; Fantasy; Fine Arts; Historical Fiction; Language and Reading; Poetry; Sciences and Mathematics, Social Studies; and Traditional Literature. In addition to the author and title, each annotation lists illustrators where applicable and the recommended age range of potential readers. A selected list of literary awards given to children's books published between 1988 and 1992; a description of popular booklists; author, illustrator, subject, and title indexes; and a directory of publishers are attached.