Residential Density Guide for Landcom Project Teams

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE UNDERCROFT We Must Expire in Hope{ of Resurrection to Life Again

THE UNDERCROFT We must Expire in hope{ of Resurrection to Life Again 1 Editorial Illu{tration{ Daniel Sell Matthew Adams - 43 Jeremy Duncan - 51, 63 Anxious P. - 16 2 Skinned Moon Daughter Cedric Plante - Cover, 3, 6, 8, 9 Benjamin Baugh Sean Poppe - 28 10 101 Uses of a Hanged Man Barry Blatt Layout Editing & De{ign Daniel Sell 15 The Doctor Patrick Stuart 23 Everyone is an Adventurer E{teemed Con{ultant{ Daniel Sell James Maliszewski 25 The Sickness Luke Gearing 29 Dead Inside Edward Lockhart 41 Cockdicktastrophe Chris Lawson 47 Nine Summits and the Matter of Birth Ezra Claverie M de in elson Ma ia S t y a it mp ic of Authent Editorial Authors live! Hitler writes a children’s book, scratches his name off and hides it among the others. Now children grow up blue and blond, unable to control their minds, the hidden taint in friendly balloons and curious caterpillars wormed itself inside and reprogrammed them into literary sleeper agents ready to steal our freedom. The swine! We never saw it coming. If only authors were dead. But if authors were dead you wouldn’t be able to find them, to sit at their side and learn all they had to say on art and beautiful things, on who is wrong and who is right, on what is allowed and what is ugly and what should be done about this and that. We would have only words and pictures on a page, if we can’t fill in the periphery with context then how will we understand anything? If they don’t tell us what to enjoy, how to correctly enjoy it, then how will we know? Who is right and who is mad? Whose ideas are poisonous and wrong? Call to arms! Stop that! Help me! We must slather ourselves in their selfish juices. -

2021-2022 Parent Handbook

2021-2022 PARENT HANDBOOK “This is the hope we have - a hope in a new humanity that will come from this new education, an education that is collaboration of man and the universe….” -Dr. Maria Montessori i | Page Welcome to Undercroft Montessori School! To both new and returning families, we extend a warm welcome to the new school year! We are so happy you are part of our Undercroft community. Over the course of this year your children will grow in a Montessori environment designed to cultivate qualities of independence, confidence, competence, leadership and a love of learning. Parents are important teachers in the lives of their children and we are honored to partner with you in support of your child’s learning and development. The strength of that partnership is an important foundation for your child’s success in school. We are committed to our relationships with parents and rely on your communication, support, and involvement to ensure a successful experience for your child. As we begin Undercroft’s 57th year, we are delighted to share the many wonderful things Undercroft has to offer. Please review carefully the information included in this handbook. It is intended to acquaint you with the policies and procedures of the school. It is important that you read it thoroughly. This summer, we will review and update our pandemic plan, which summarizes the strategies we will employ to safeguard the health and well-being of our school community in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. This plan remains a living document, and will be subject to change throughout the year as we respond to changing guidelines for schools, as well as changing circumstances related to the pandemic in the greater community. -

Wherever You Are in Your Journey of Faith, There Is a Place for You Here

ST. PAUL'S EPISCOPAL CHURCH BENICIA, CA Wherever you are in your journey of faith, there is a place for you here Page 1 of 16 Table of Contents Page Number 1. Letter of introduction 3 2 Parish goals 4 3. Staff list and job descriptions 6 4. Financial summary 9 5. Physical church buildings & facilities 11 6. Areas of ministry focus 12 7. Blessings & challenges 13 8. Congressional assessment survey summary 14 9. Our place in the Episcopal Church 15 St. Paul’s Episcopal Church Benicia, California http://www.stpaulsbenicia.org Page 2 of 16 Letter of Introduction St. Paul’s Benicia, a congregation rich both in history and living presence is seeking a qualified person to serve as its Rector. We are a theologically progressive and adaptable church with a friendly atmosphere. Our lay leaders strive to be truly representative of St. Paul’s and want to know what the people think. There is a hunger for spiritual growth under the leadership of a Rector who can continue the tradition of bringing the best out of St. Paul’s worshiping community. The resources we bring include a beautiful nineteenth century Carpenter Gothic church building which can seat 125 persons – up to 150 on special occasions. The undercroft provides meeting and classroom space. This is complemented by the Parish Hall and kitchen. A New England salt-box house, the former parsonage, built in the1790s, disassembled and shipped round the horn in 1868, provides office and additional meeting space. The congregation counts 240 members with an average Sunday attendance of 115 at two services. -

A Strategic Plan for Restoration and Improvement of Buildings and Grounds

A Strategic Plan for Restoration and Improvement of Buildings and Grounds April 19, 2021 1 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..4 First Priority Projects…………………………………………………………………………………………………7 Second Priority 1 Projects………………………………………………………………………………………….13 Second priority 2 Projects………………………………………………………………………………………...16 Strategic Planning Cost Estimates, September 4, 2020.……………………………………………..20 Appendix A – South Entrance Sketches………………………………………………………..….28 Appendix B – Replacement Window Manufacturers………………………………………….30 Appendix C – Existing Door Photos………………………………………………………………….34 Appendix D – Existing Light Fixtures Photos…………………………………………………….57 Drawings………………………………………………………………………………………………………70 Strategic Plan Budget Estimate details……………………………………………………………..73 Inspiration………………………………………………………………………………………………………………81 3 4 PREFACE The Cathedral of All Saints is a treasure of North American sacred architecture and one of the largest neo- Gothic structures in North America. It is ranked with St. Patrick's Cathedral and the Cathedral of St. John the Divine in New York City and with the National Cathedral in Washington, D.C. The Cathedral of All Saints is known as the Pioneer Cathedral because it was the first cathedral built in the United States on the scale and in the style of the great cathedrals of England. It is on the National Register of Historic Places and is the mother church of the Episcopal Diocese of Albany. It is one of the most unique public buildings in Albany and part of the distinctive heritage -

20 South Avenue, Oldfield Park, Bath, BA2

20 South Avenue, Oldfield Park, Bath, £400,000 BA2 3PY A truly exquisite 983sqft late Victorian two storey home with stunning • 983sqft panoramic city views, undercroft, loft conversion potential and a lengthy rear garden. Carefully crafted and fully refurbished accommodation with an excellent • Panoramic city AirB&B track record and packed with character features. Two double views bedrooms, huge first floor bathroom, two open plan receptions, modern kitchen and useful undercroft utility/office. Boarded loft with Velux. 200yds to Moorland • 73ft x 15ft rear Rd shops. Unrestricted street parking. Sole Agents gardens • Retained character • Further loft expansion potential Property Description REAR GARDEN 73ft x 15ft - patio, gravelled terrace, lawns ENTRANCE HALL Top lit panelled front door, meter cupboard, flower beds and borders. Walls, hedges and fences to side and exposed floorboards, radiator, coved ceiling. rear. Gated rear pedestrian access. SITTING ROOM Two double glazed front windows, radiator, UNDERCROFT UTILITY/OFFICE Double glazed rear door from exposed floorboards, ornate cast iron fireplace with tiled inset garden, double glazed side window, Viessmann gas combination and slate hearth. Archway to dining room. boiler, plumbing for washing machine, desk space/study area, tiled floor. DINING ROOM Double glazed rear window, radiator, ashlar fireplace with inset shelving, exposed floorboards, stairs to first AGENTS NOTES South Avenue was built in 1888, by Herbert S floor with cupboard under, coved ceiling, ceiling rose. Keeling (who went on to live briefly at No1) and, by 1892, all 40 houses were first occupied barring Nos 2, 11,12 and 17. In 1902, KITCHEN Double glazed rear window, double glazed side door the residents of this section of the road were; to garden, radiator, fitted fridge/freezer, base and wall units with 17 - James Norman (foundryman) worktops and inset sink/drainer, inset five ring gas hob with hood 18 - William T Lansdown (labourer) over, fitted double oven, fitted dishwasher. -

Design Option #2 – Construction of an Undercroft Only

DESIGN OPTION #2 – CONSTRUCTION OF AN UNDERCROFT ONLY In December 2011, the Vestry directed the Steering Committee to explore three alternative designs – renovation of Baxter House; construction of only a new undercroft under the Parish Hall; and, construction of only a new second floor above the Parish Hall. This is a report on the second of those options, construction of only a new undercroft under the Parish Hall. The Design This design calls for full excavation under the Parish Hall. This would necessitate the removal and replacement of the Parish Hall floor. That space would be built out into a new undercroft area, completely committed to our clergy and staff offices. As shown in the accompanying drawings, there would be private offices for the Rector, Assistant Rector and Director of Music; open space work areas for the Youth Director, Parish Administrators and Answering Angels, a conference room, a copy room and an archives/file room. Because the stairs and elevator would not be moved from their current location, there would be no renovation of the current undercroft stair/elevator foyer; however, the current restrooms would be renovated to allow access to the new undercroft. Assessment On the positive side: . all of our programmed office space would fit in the new undercroft; . it would be possible, if we chose, to do some renovations to the parish hall and kitchen; . the current estimated cost of $860,000 in direct construction costs and total project cost of $2.3 million, when compared with the total expected revenue from the campaign and the sale of Baxter House, would give us some money for additional renovations (for example, redecorating of the Parish Hall and renovation of the kitchen) and/or capital improvements; and, . -

The Apartment Construction Cost Demonstration Project Research Project “An Affordable Place to Live Is More Than Just Housing and Household Costs

THE APARTMENT CONSTRUCTION COST DEMONSTRATION PROJECT RESEARCH PROJECT “AN AFFORDABLE PLACE TO LIVE IS MORE THAN JUST HOUSING AND HOUSEHOLD COSTS. IT INCLUDES THE NEIGHBOURHOODS THAT ARE CREATED AND THE COMMUNITIES THAT EMERGE. IT IS ABOUT THE CONNECTIONS THAT ARE SUPPORTED, SERVICES THAT ARE PROVIDED AND THE LIFESTYLES THAT ARE SUSTAINED” renewalsa.sa.gov.au/projects/apartment-cost-demonstration-project 3 THE APARTMENT CONSTRUCTION COST DEMONSTRATION PROJECT RESEARCH REPORT JUNE 2016 Disclaimer: This Report was produced by The information contained in this document is only intended to be a report of the experience of Renewal SA in relation to a specific development project undertaken by Renewal SA. The Government of South Australia does not warrant (express or implied) that the use of any of the information (in whole or in part) contained in this document will deliver the same or similar results or outcomes for other development projects. No warranty, express or implied is made regarding the accuracy, adequacy, completeness, reliability, suitability or usefulness of the whole or any part of the information In partnership with our contained in this document. You should seek your own independent expert advice Builder Partner and make your own enquiries and satisfy yourself of all aspects of the information contained in this document. Any use or reliance on any of information contained in this document is at your own risk in all things. The Government of South Australia and its servants and its agents disclaim all liability and responsibility (including for negligence) for any direct or indirect loss or damage which may be suffered by any person through using or relying on any of the information contained in this document. -

2018 Capital Campaign JANUARY 28, 2018 175Th Anniversary Christ Church Pelham 1843 – 2018

THE PARISH OF CHRIST THE REDEEMER PELHAM MANOR , NEW YORK 2018 Capital Campaign JANUARY 28, 2018 175th Anniversary Christ Church Pelham 1843 – 2018 Almighty God, whose loving hand hath given us all that we possess: Grant us grace that we may honor thee with our substance, and, remembering the account which we must one day give, may be faithful stewards of thy bounty, through Jesus Christ our Lord. Amen. - BCP Honoring our past, celebrating our present, planning for our future 2018 marks the 175th Anniversary of Christ Church. We offer our prayers and praises to Almighty God for sustaining our parish through the generations, and we give thanks for the ministry and leadership of our founder Robert Bolton and all who have made Christ Church their spiritual home. We will be marking this milestone with worship and celebratory events, at which we will gather as a community to honor our past, celebrate our present and plan for our future. We are the beneficiaries of the prayers, hard work, stewardship and love of those who have come before us. They are the reason we have this beautiful space in which we can gather, to worship our Lord Jesus Christ, share fellowship and be in ministry together to do God’s work. We are now called by God to ensure that future generations will find a spiritual home in this beautiful, historic church. One of the best ways in which we can honor our heritage is by making a commitment to the future of Christ Church. Over the past ten years, we have invested a significant amount of time and capital, repairing and restoring many areas of our buildings. -

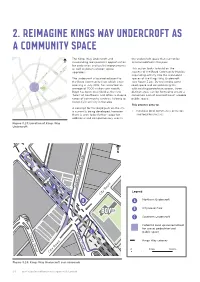

2. Reimagine Kings Way Undercroft As a Community Space

FEDERATION SQUARE FLINDERS STREET T STATION T EE EE R R ST ST S NS ER ND COLLI FLI ER HAMER V E GAT HALL YARRA RI UTH SO NUE 2. reimagine kingsAVE way undercroft as ALEXANDRA AVENUE R ATE SHW FRE CE PLA T ARTS ST KILDA RO EE CENTRE G T a community spaceN TR E S NU NI EE AVE T N W TR O R G S U H FA A IT T L S D IN NATIONAL L The Kings WayG AUndercroftLLERY OF and the undercroft space that cannot be VICTORIA N T surrounding area presents opportunities accommodated in the park. SOUTH BANK REE BOUL T H for pedestrianE and cyclist improvements S VA G RD E T This action looks to build on the G ANA as well as potential open space V D P OW REE S A T T K S D R E upgrades. success of the Boyd Community Hub by A EE R S BRI T N expanding activity into the redundant CITY RO QUEE The undercroft is located adjacent to spaces of the Kings Way Undercroft B A STREELS T O the Boyd Community Hub, which since (see figure 3.24). By reclaiming some N T opening in July 2012, has attracted an road space and consolidating this BOYD average of 7000 visitors per month. with existing pedestrian spaces, three Boyd has been described as the new distinct areas can be formed to create a KI NG ‘heart’ of Southbank and offers a diverse combined area of one hectare of useable MORAY STRE Y S W FREEWA A TE range of community services, helping to public space. -

Wells Cathedral, but ‘We Had a Very Listed Building Control

WELLS 01 PROJECT ARCHITECT: CATHEDRAL Martin Stancliffe, New entry cloister, Education and Music Purcell Miller Tritton Resource Centre, chapter house CATHEDRAL ARCHITECT: undercroft, works yard Peter Bird In some ways, the great medieval cathedrals are dinosaurs: creations of another era, fascinating, impressive and inspiring – but ill-equipped for the demands of the twenty-first century. Yet their continued significance is not to be doubted. Wells attracts some 470,000 visitors a year,170,000 of whom attend one of the 1,730 services, concerts, educational visits and other events organised by the cathedral. That’s almost five events a day, each with its own logistical demands, each attracting a different public. So it is easy to understand why the chapter at Wells had, by the late 1990s, begun to feel as if they were reaching a kind of evolutionary crossroads. There was no safe accommodation for visiting school groups, no disabled access to many areas of the cathedral church itself, and no covered route to the visitors’ toilets. The cathedral shop and restaurant occupied one walk of the medieval cloister; part of the Song School filled another. Girl choristers practised in the chapter house undercroft, which had otherwise become a large storeroom; choirs of both sexes robed here, too. Child protection legislation and the Disability Discrimination Act increased the imperative for change. The status quo was untenable. It took some time for the right solution to emerge. The first scheme was opposed by several consultees. It took all the negotiation skills of the cathedral authorities and planning advisors, including English Heritage and the CFCE, to arrive at the eventual answer – a design which balanced the building’s extraordinary significance with the needs of modern users and which was capable of attracting consent and funding. -

THE TWELFTH-CENTURY AISLED HALL of LEICESTER CASTLE: a RE-ASSESSMENT Nick Hill

THE TWELFTH-CENTURY AISLED HALL OF LEICESTER CASTLE: A RE-ASSESSMENT Nick Hill A recent programme of research, accompanied by archaeological excavation and dendrochronology, has confirmed the Great Hall of Leicester Castle as the earliest known standing aisled hall in Britain, now tree-ring dated to 1137–62. It was built for Earl Robert II of Leicester, one of the greatest magnates of the period, probably in the 1150s when he was at the height of his powers. The form of the main twelfth-century roof structure, with timber arcades and a former clerestorey, was established in previous work of the 1980s. The current study has added detailed analysis of the external masonry walls, including the uncovering of two service doorways. Archaeological excavation established that the aisle posts were originally earth-fast. Drawing on earlier documentary study, a revised reconstruction of the original building form is proposed, relating the upper roof structure to the original masonry walls, aisles and floor level. Evidence indicates that a small service building was attached to the north gable, with a detached chamber block located to the south. The relationship of Leicester to other early aisled halls is also explored. INTRODUCTION The Great Hall of Leicester Castle is a remarkable survivor. Of the rest of the extensive castle buildings, which reached their heyday under John of Gaunt in the late fourteenth century, little remains except for parts of two gatehouses. The Great Hall itself underwent major alteration in the early sixteenth century, was entirely re- fronted in the 1690s, subdivided internally in 1821, and further altered and extended in 1858. -

Design Review Guidelines

Brambleton Community Association Design Guidelines Revised 08/09/2021 www.brambletonhoa.com INTRODUCTION 4 VISION, MISSION & CORE VALUES 4 PURPOSE OF THE DESIGN GUIDELINES 4 BASIS FOR AND OBJECTIVES OF RESTRICTIVE COVENANTS 4 ROLE AND AUTHORITY OF THE COVENANTS COMMITTEE 5 EXTERIOR MODIFICATIONS REQUIRING REVIEW AND APPROVAL BY THE COMMITTEE 7 DESIGN REVIEW CRITERIA 8 APPLICATION REVIEW AND ENFORCEMENT PROCEDURES 11 PROPERTY MAINTENANCE STANDARDS 16 GENERAL PROJECT GUIDELINES 17 DESIGN GUIDELINES 20 ADDITIONS/ALTERATIONS 21 AIR CONDITIONING UNITS/HEAT PUMPS 23 ANTENNAS AND SATELLITE DISHES 24 ARBORS 25 ARTIFICIAL OR SYNTHETIC TURF/OUTDOOR CARPETING 27 ATTIC VENTILATORS 28 AWNINGS/SUN CONTROL DEVICES 29 CHIMNEYS/FLUES/ATTIC VENTS 31 CLOTHES LINES/WIND DRYING DEVICES 33 COLOR CHANGES 34 COMPOST BINS 35 DECKS 37 DOG HOUSES AND DOG RUNS 43 DOORS 44 DRAINS/FRENCH DRAINS 48 DRIVEWAYS/PARKING PADS 49 EXTERIOR DECORATIVE OBJECTS AND LANDSCAPE FEATURES 51 EXTERIOR LIGHTING 52 FENCES 56 FIREWOOD 62 FLAGPOLES/FLAGSTAFFS 63 GAZEBOS 64 GUTTERS AND DOWNSPOUTS 65 HANDICAPPED ACCESS FACILITIES 66 HOLIDAY DECORATIONS AND LIGHTING 66 HOT TUBS/SPAS 67 HOUSE NUMBERS 68 IRRIGATION 69 LANDSCAPING 70 MAILBOXES 73 OUTDOOR KITCHENS/PERMANENT GRILL AREAS/PORTABLE GRILLS 74 OUTDOOR FIREPLACE/FIREPIT 76 OUTDOOR FURNITURE 77 OUTDOOR STORAGE 77 PATIOS 78 PEST CONTROL DEVICES 79 PERGOLAS 80 RAIN BARRELS 82 RECREATION AND PLAY EQUIPMENT 83 ROOFING 88 SCREENED/OPEN PORCHES 90 SECURITY DEVICES 92 SHADE STRUCTURES/CANOPIES/SAILS 94 STORAGE CONTAINERS/SHEDS 95 SHUTTERS 97