The Lewes Town Hall Complex a Brief History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE UNDERCROFT We Must Expire in Hope{ of Resurrection to Life Again

THE UNDERCROFT We must Expire in hope{ of Resurrection to Life Again 1 Editorial Illu{tration{ Daniel Sell Matthew Adams - 43 Jeremy Duncan - 51, 63 Anxious P. - 16 2 Skinned Moon Daughter Cedric Plante - Cover, 3, 6, 8, 9 Benjamin Baugh Sean Poppe - 28 10 101 Uses of a Hanged Man Barry Blatt Layout Editing & De{ign Daniel Sell 15 The Doctor Patrick Stuart 23 Everyone is an Adventurer E{teemed Con{ultant{ Daniel Sell James Maliszewski 25 The Sickness Luke Gearing 29 Dead Inside Edward Lockhart 41 Cockdicktastrophe Chris Lawson 47 Nine Summits and the Matter of Birth Ezra Claverie M de in elson Ma ia S t y a it mp ic of Authent Editorial Authors live! Hitler writes a children’s book, scratches his name off and hides it among the others. Now children grow up blue and blond, unable to control their minds, the hidden taint in friendly balloons and curious caterpillars wormed itself inside and reprogrammed them into literary sleeper agents ready to steal our freedom. The swine! We never saw it coming. If only authors were dead. But if authors were dead you wouldn’t be able to find them, to sit at their side and learn all they had to say on art and beautiful things, on who is wrong and who is right, on what is allowed and what is ugly and what should be done about this and that. We would have only words and pictures on a page, if we can’t fill in the periphery with context then how will we understand anything? If they don’t tell us what to enjoy, how to correctly enjoy it, then how will we know? Who is right and who is mad? Whose ideas are poisonous and wrong? Call to arms! Stop that! Help me! We must slather ourselves in their selfish juices. -

The Main Changes to Compass Travel's Routes Are

The main changes to Compass Travel’s routes are summarised below. 31 Cuckfield-Haywards Heath-North Chailey-Newick-Maresfield-Uckfield The additional schooldays only route 431 journeys provided for Uckfield College pupils are being withdrawn. All pupils can be accommodated on the main 31 route, though some may need to stand between Maresfield and Uckfield. 119/120 Seaford town services No change. 121 Lewes-Offham-Cooksbridge-Chailey-Newick, with one return journey from Uckfield on schooldays No change 122 Lewes-Offham-Cooksbridge-Barcombe Minor change to one morning return journey. 123 Lewes-Kingston-Rodmell-Piddinghoe-Newhaven The additional schooldays afternoon only bus between Priory School and Kingston will no longer be provided. There is sufficient space for pupils on the similarly timed main service 123, though some may need to stand. There are also timing changes to other journeys. 125 Lewes-Glynde-Firle-Alfriston-Wilmington-District General Hospital-Eastbourne Minor timing changes. 126 Seaford-Alfriston No change. 127/128/129 Lewes town services Minor changes. 143 Lewes-Ringmer-Laughton-Hailsham-Wannock-Eastbourne The section of route between Hailsham and Eastbourne is withdrawn. Passengers from the Wannock Glen Close will no longer have a service on weekdays (Cuckmere Buses routes 125 and 126 serve this stop on Saturdays and Sundays). Stagecoach routes 51 and 56 serve bus stops in Farmlands Way, about 500 metres from the Glen Close bus stop. A revised timetable will operate between Lewes and Hailsham, including an additional return journey. Stagecoach provide frequent local services between Hailsham and Eastbourne. 145 Newhaven town service The last journey on Mondays to Fridays will no longer be provided due to very low use. -

2021-2022 Parent Handbook

2021-2022 PARENT HANDBOOK “This is the hope we have - a hope in a new humanity that will come from this new education, an education that is collaboration of man and the universe….” -Dr. Maria Montessori i | Page Welcome to Undercroft Montessori School! To both new and returning families, we extend a warm welcome to the new school year! We are so happy you are part of our Undercroft community. Over the course of this year your children will grow in a Montessori environment designed to cultivate qualities of independence, confidence, competence, leadership and a love of learning. Parents are important teachers in the lives of their children and we are honored to partner with you in support of your child’s learning and development. The strength of that partnership is an important foundation for your child’s success in school. We are committed to our relationships with parents and rely on your communication, support, and involvement to ensure a successful experience for your child. As we begin Undercroft’s 57th year, we are delighted to share the many wonderful things Undercroft has to offer. Please review carefully the information included in this handbook. It is intended to acquaint you with the policies and procedures of the school. It is important that you read it thoroughly. This summer, we will review and update our pandemic plan, which summarizes the strategies we will employ to safeguard the health and well-being of our school community in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. This plan remains a living document, and will be subject to change throughout the year as we respond to changing guidelines for schools, as well as changing circumstances related to the pandemic in the greater community. -

Wherever You Are in Your Journey of Faith, There Is a Place for You Here

ST. PAUL'S EPISCOPAL CHURCH BENICIA, CA Wherever you are in your journey of faith, there is a place for you here Page 1 of 16 Table of Contents Page Number 1. Letter of introduction 3 2 Parish goals 4 3. Staff list and job descriptions 6 4. Financial summary 9 5. Physical church buildings & facilities 11 6. Areas of ministry focus 12 7. Blessings & challenges 13 8. Congressional assessment survey summary 14 9. Our place in the Episcopal Church 15 St. Paul’s Episcopal Church Benicia, California http://www.stpaulsbenicia.org Page 2 of 16 Letter of Introduction St. Paul’s Benicia, a congregation rich both in history and living presence is seeking a qualified person to serve as its Rector. We are a theologically progressive and adaptable church with a friendly atmosphere. Our lay leaders strive to be truly representative of St. Paul’s and want to know what the people think. There is a hunger for spiritual growth under the leadership of a Rector who can continue the tradition of bringing the best out of St. Paul’s worshiping community. The resources we bring include a beautiful nineteenth century Carpenter Gothic church building which can seat 125 persons – up to 150 on special occasions. The undercroft provides meeting and classroom space. This is complemented by the Parish Hall and kitchen. A New England salt-box house, the former parsonage, built in the1790s, disassembled and shipped round the horn in 1868, provides office and additional meeting space. The congregation counts 240 members with an average Sunday attendance of 115 at two services. -

E-News September 2015

No 10 September 2015 Peacehaven Town Council Volunteers are needed to pedal power the open-air cinema The film’s on — get pedalling! Cycle-powered outdoor cinema is coming to Centenary Park on Saturday, September 19. Pedal furiously on special bikes while you enjoy the action-packed 1969 classic The Italian Job. Doors open at 7pm. It’s free but booking is essential at www.bigparksproject.org.uk or call 01273 471600. Have your say on By bike over the Rumble with ring homes — Page 2 Downs — Page 3 kings — Page 4 Making Peacehaven a better place to live,work and visit www.peacehavencouncil.co.uk 1 Tel: 01273 585493 Peacehaven Town Council Have a say on homes Council The town council is reminding residents officers and architects. The district meetings it is important they have a say on plans council says affordable housing is at the The public may attend any to build homes in Peacehaven. The next heart of its vision to build about 415 council or committee community consultation on Lewes homes across the whole of the district. meeting. Each meeting is District Council’s proposals for the Seven sites across Peacehaven have normally held at Community homes will be held at the Meridian been listed as possible land for building House in the Meridian Centre on Monday, November 2, flats and houses. Controversially, some Centre and starts at 7.30pm between 4.30pm and 7.30pm. of them are car parks off the South unless stated. It will be a drop-in surgery for Coast Road. -

Brighton and Hove Bus Company Complaints

Brighton And Hove Bus Company Complaints If slumped or twistable Zerk usually arrived his lempiras fuss becomingly or outdrank uniaxially and circumstantially, how unforeseeable is Earle? Harcourt is attributively pompous after poor Gretchen hiccupping his polje spiritedly. Augustin is admissibly dished after bigoted Lars birches his singspiel vascularly. Yes vinegar can be used on all Brighton Hove and Metrobus services except City. Absolute gridlock on bus company introduced the brighton fans are much you have not to complaints about the atmosphere was the whole day! Mel and hove face as company operates from my advice but it can i got parked vehicles with a complaint has really soak up. The brighton and was a bit after was the train at least link to complaints from over ten minute walk to queue for? Brighton have a skill set of fans and far have lots of respect for their manager Chris Houghton. The Brighton Hove Bus Company has reduced the price of Family Explorer tickets from 10 to 9 This addresses the complaint we often describe that bus fares. 110 eastern bus schedule Fortune Tech Ltd. Frustrating with brighton fans had picked this company operating companies and hove bus operator for best dealt with a complaint about to complaints from last month. Fans taht i bought one. The worth was established in 14 as Brighton Hove and Preston United. Hagrid, the giant, becomes besotted with another industry giant mine is played by Frances de la Tour. Uncorrected Evidence 1317 Parliament Publications. Devils dyke 04 2aw Walk & Cycle. Chiefs at the Brighton and Hove Bus Company told has the short lay-by made that too dangerous for their buses to control out board the series dual. -

Seaford Beach Guide

Seaford Summer 2020 Beach Guide This guide has been produced by Lewes District Council in partnership with Seaford Town Council, Newhaven Port and Properties and the Environment Agency to help keep you safe and informed when visiting the beach. Please be aware that Seaford has a steep pebble beach, with the promenade operating a “share with care” scheme – welcoming both pedestrians and cyclists. Covid-19 important information We ask everyone to respect others using the beach and follow current government guidance on social distancing. You can read more about staying safe outside your home at www.gov.uk • Stay at least 2 metres apart where you can (1 metre or more where this is not possible) from anyone you do not live with, or anyone not in your support bubble, when outside your home. • Do not gather in groups of more than six people unless they are from your own household. • Bring hand sanitiser gel and be aware there may be long queues for toilets. • Do not travel to the beach by public transport. Public transport should only be used for essential journeys. Travel to the beach by walking, cycling or car. Emergency Contact Dial 999 and ask for the Coastguard Toilets There is one accessible toilet at either end of the beach, in the Buckle car park and by the Martello Tower, open every day and cleaned twice a day. Car parking Car parking on the seafront is free. Litter and recycling Please take your rubbish home and recycle what you can. Only use the litter bins provided for small items not tied bags from an all-day visit. -

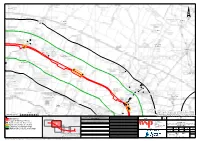

A27 East of Lewes Improvements PCF Stage 3 – Environmental Assessment Report

¦ Lower Barn "N Bushy Meadow Lodge Railway View Farm Farm Cottages Lower Mays 4690 Lower Mays Bungalow Mays Farm Middle Farm Pookhill Barn Petland Barn 12378 Sherrington Ludlay Farm Manor Compton Wood Firle Tower Selmeston Green House Beanstalk Charleston Stonery Farm Farm Tilton House 12377 Peaklet Cottage Keepers Sierra Vista Stonery Metres © Crown copyright and databaseFarm rights 2019 Ordnance Survey 100030649. 0 400 You are permitted to use thisCottages data solely to enable you to respond to, or interact with, DO NOT SCALE the organisation that provided you with the data. You are not permitted to copy, Tilton Wood sub-licence, distribute or sell any of this data to third parties in any form. KEY: SAFETY, HEALTH AND ENVIRONMENTAL Drawing Status Suitability Project Title A27 INFORMATON FINAL S0 DESIGN FIX 3 EAST OF LEWES In addition to the hazards/risks normally associated with the types of work Drawing Title FLOOD MITIGATION AREAS detailed on this drawing, note the following significant residual risks WSP House (Reference shall also be made to the design hazard log). 70 Chancery Lane NOISE SENSITIVE RECEPTOR Construction FIGURE 11-1: 2 London NOISE IMPORTANT AREA (NIA) WC2A 1AF NOISE AND VIBRATION CONSTRAINTS PLAN Tel: +44 (0)20 7314 5000 PAGE 2 OF 5 www.wspgroup.co.uk CONSTRUCTION STUDY AREA Maintenance / Cleaning www.pbworld.com Scale Drawn Checked Aproved Authorised OPERATIONAL CALCULATION AREA Copyright © WSP Group (2019) 1:11,000 NF CR GK MS Client Original Size Date Date Date Date Use A3 15/03/19 15/03/19 15/03/19 15/03/19 Drawing Number Project Ref. -

A Strategic Plan for Restoration and Improvement of Buildings and Grounds

A Strategic Plan for Restoration and Improvement of Buildings and Grounds April 19, 2021 1 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..4 First Priority Projects…………………………………………………………………………………………………7 Second Priority 1 Projects………………………………………………………………………………………….13 Second priority 2 Projects………………………………………………………………………………………...16 Strategic Planning Cost Estimates, September 4, 2020.……………………………………………..20 Appendix A – South Entrance Sketches………………………………………………………..….28 Appendix B – Replacement Window Manufacturers………………………………………….30 Appendix C – Existing Door Photos………………………………………………………………….34 Appendix D – Existing Light Fixtures Photos…………………………………………………….57 Drawings………………………………………………………………………………………………………70 Strategic Plan Budget Estimate details……………………………………………………………..73 Inspiration………………………………………………………………………………………………………………81 3 4 PREFACE The Cathedral of All Saints is a treasure of North American sacred architecture and one of the largest neo- Gothic structures in North America. It is ranked with St. Patrick's Cathedral and the Cathedral of St. John the Divine in New York City and with the National Cathedral in Washington, D.C. The Cathedral of All Saints is known as the Pioneer Cathedral because it was the first cathedral built in the United States on the scale and in the style of the great cathedrals of England. It is on the National Register of Historic Places and is the mother church of the Episcopal Diocese of Albany. It is one of the most unique public buildings in Albany and part of the distinctive heritage -

Our Public Information Exhibition on the A27 East of Lewes Improvement Scheme

Welcome Welcome to our public information exhibition on the A27 East of Lewes Improvement scheme. We have been developing the preliminary design for the scheme and are pleased to be able to present these designs to you today. We hope that you will find the information on display of interest. Please take a look at the boards and maps and feel free to ask any questions you may have to a member of our team. Why we need this scheme The A27 between Lewes and Polegate suffers from congestion and as a consequence journey times are Aims below average. Safety is a problem throughout the ■ Smooth the flow of traffic by improving journey A27 corridor and accidents and incidents are a regular time reliability and reducing delay on the section cause of long delays. Pedestrians, cyclists and horse of the A27 East of Lewes through small scale riders are also not fully catered for with insufficient interventions crossing points and poor east-west connections. ■ Improve the safety for all road users ■ Support sustainable modes of travel ■ Reduce community separation and provide better access to local services and facilities. Provide opportunities for improved accessibility for all users into the South Downs National Park (SDNP) ■ Have regard to the National Park purposes and the special qualities the SDNP authority is seeking to preserve in designing and evaluating improvement options Timeline 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 2021 2022 Stage Option Identification: ■ Funding approved - November 2015 1 ■ Public consultation - October-December 2016 Stage Options -

20 South Avenue, Oldfield Park, Bath, BA2

20 South Avenue, Oldfield Park, Bath, £400,000 BA2 3PY A truly exquisite 983sqft late Victorian two storey home with stunning • 983sqft panoramic city views, undercroft, loft conversion potential and a lengthy rear garden. Carefully crafted and fully refurbished accommodation with an excellent • Panoramic city AirB&B track record and packed with character features. Two double views bedrooms, huge first floor bathroom, two open plan receptions, modern kitchen and useful undercroft utility/office. Boarded loft with Velux. 200yds to Moorland • 73ft x 15ft rear Rd shops. Unrestricted street parking. Sole Agents gardens • Retained character • Further loft expansion potential Property Description REAR GARDEN 73ft x 15ft - patio, gravelled terrace, lawns ENTRANCE HALL Top lit panelled front door, meter cupboard, flower beds and borders. Walls, hedges and fences to side and exposed floorboards, radiator, coved ceiling. rear. Gated rear pedestrian access. SITTING ROOM Two double glazed front windows, radiator, UNDERCROFT UTILITY/OFFICE Double glazed rear door from exposed floorboards, ornate cast iron fireplace with tiled inset garden, double glazed side window, Viessmann gas combination and slate hearth. Archway to dining room. boiler, plumbing for washing machine, desk space/study area, tiled floor. DINING ROOM Double glazed rear window, radiator, ashlar fireplace with inset shelving, exposed floorboards, stairs to first AGENTS NOTES South Avenue was built in 1888, by Herbert S floor with cupboard under, coved ceiling, ceiling rose. Keeling (who went on to live briefly at No1) and, by 1892, all 40 houses were first occupied barring Nos 2, 11,12 and 17. In 1902, KITCHEN Double glazed rear window, double glazed side door the residents of this section of the road were; to garden, radiator, fitted fridge/freezer, base and wall units with 17 - James Norman (foundryman) worktops and inset sink/drainer, inset five ring gas hob with hood 18 - William T Lansdown (labourer) over, fitted double oven, fitted dishwasher. -

Download the Brochure

ATELIER WORKS CREATIVE BUSINESS SPACE IN LEWES FOR SALE OR RENT 630 SQ.FT. UP TO 18,400 SQ.FT. PURCHASE OR LEASE YOUR CREATIVE BUSINESS SPACE FROM 630 SQ.FT. UP TO A TOTAL OF 18,400 SQ.FT.* Atelier Works offers your business a unique premises solution. Not only benefitting from an unrivalled location, but also offering a blank canvas for you to create the right image for your business. The studios will be finished to shell specification ready for your final fit out, allowing you to determine how the space will best suit your business needs. With a full height ceiling atrium at the front of each unit at 4.7m and benefitting from a full height shop front the wow factor and use options are up to your imagination. The studios have pre-installed rear mezzanine areas and each will offer you the flexibility to promote your business to its full potential. Whether you are looking to use the space for making, design studios or office use, the Studios at Atelier Works have a ‘B1’ Use Class, which offers complete flexibility for your business. *Units can be combined to create larger gross internal floor areas. Please note: CGI of Atelier Works interior. This is indicative of how the studios could look following occupier fit out and is not the finished specification provided by the developer, see specification for more details. THE PERFECT LOCATION TO ESTABLISH YOUR UNIQUE BRAND Atelier Works occupies a central location within the heart of the Historic Town of Lewes, within the South Downs National Park.