Phelsuma13 Revised.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Phelsuma13 Revised.Indd

Phelsuma 13; 25-43 used to obtain population estimates based on the number of moths observed and the Captive management of the Frégate Island giant tenebrionid beetle average time taken for moths to return to the study plants. Moths, returned to the plants Polposipus herculeanus after 4.5 hours (range=3-6). Numbers of moths increased throughout the day, with a maximum number in July 1999 of 22 Cephonodes hylas, 2 C. tamsi and 1 M. alluaudi, AMANDA FERGUSON & PAUL PEARCE-KELLY giving a density estimate of 352 per km2 for C. hylas, 32 C. tamsi and 16 Macroglossum 2 alluaudi. On Silhouette, there are 10km of optimal habitat for the bee hawkmoths and Invertebrate Conservation Unit, Zoological Society of London, Regent’s Park, London 2 100km for M. alluaudi, giving population estimates of 3520 C. hylas, 320 C. tamsi NW1 4RY, U.K. and 1600 M. alluaudi. Since then, the area is visited one per day in the early afternoon [[email protected] & [email protected]] during the seasons when hawkmoths are observed. Abstract: The Frégate Island giant tenebriond beetle Polposipus herculeanus is a Critically Endangered species restricted to Frégate Island, Seychelles. The ex-situ conservation programme at the Fig 1. Activity patterns of hawkmoths in 1999 Zoological Society of London and the European Endangered Species Programme are described. Captive propagation started in 1996 and has been highly successful with the programme holding 980 adult beetles by the end of 2003. Reproductive data is described and the finding of pathological infections of the fungus Metarhizium anisopliae var. -

Ecosystem Profile Madagascar and Indian

ECOSYSTEM PROFILE MADAGASCAR AND INDIAN OCEAN ISLANDS FINAL VERSION DECEMBER 2014 This version of the Ecosystem Profile, based on the draft approved by the Donor Council of CEPF was finalized in December 2014 to include clearer maps and correct minor errors in Chapter 12 and Annexes Page i Prepared by: Conservation International - Madagascar Under the supervision of: Pierre Carret (CEPF) With technical support from: Moore Center for Science and Oceans - Conservation International Missouri Botanical Garden And support from the Regional Advisory Committee Léon Rajaobelina, Conservation International - Madagascar Richard Hughes, WWF – Western Indian Ocean Edmond Roger, Université d‘Antananarivo, Département de Biologie et Ecologie Végétales Christopher Holmes, WCS – Wildlife Conservation Society Steve Goodman, Vahatra Will Turner, Moore Center for Science and Oceans, Conservation International Ali Mohamed Soilihi, Point focal du FEM, Comores Xavier Luc Duval, Point focal du FEM, Maurice Maurice Loustau-Lalanne, Point focal du FEM, Seychelles Edmée Ralalaharisoa, Point focal du FEM, Madagascar Vikash Tatayah, Mauritian Wildlife Foundation Nirmal Jivan Shah, Nature Seychelles Andry Ralamboson Andriamanga, Alliance Voahary Gasy Idaroussi Hamadi, CNDD- Comores Luc Gigord - Conservatoire botanique du Mascarin, Réunion Claude-Anne Gauthier, Muséum National d‘Histoire Naturelle, Paris Jean-Paul Gaudechoux, Commission de l‘Océan Indien Drafted by the Ecosystem Profiling Team: Pierre Carret (CEPF) Harison Rabarison, Nirhy Rabibisoa, Setra Andriamanaitra, -

Annual Review 2015

ANNUAL REVIEW 2015 01 Our mission 02 President’s statement 03 Chairman’s statement 05 Chief Executive’s statement 07 Conservation 08 Conservation science 10 Out in the field 12 Community conservation 14 Engagement 16 RZSS Edinburgh Zoo 20 2015 highlights 22 RZSS Highland Wildlife Park 26 Get involved 28 Financial summary 30 Our people and structure 31 Board, fellows and patrons 33 RZSS Edinburgh Zoo Inventory 38 RZSS Highland Wildlife Park Inventory 40 About us Front cover: Arktos the polar bear at the Highland Wildlife Park, taken by RZSS Photographer in Residence Laurie Campbell OUR MISSION Connecting people with nature. Safeguarding species from extinction. The Budongo Conservation Field Station in Uganda celebrated its 25th anniversary in 2015 Annual Review 2015 01 1 Victoria, the UK’s only female polar PRESIDENT’S bear, who arrived at the Highland Wildlife Park in March STATEMENT 2 Jayendra and Roberta, our pair of endangered Asiatic lions, were introduced to one another in April After nearly ten years, it is strange to be writing my final foreword for the Royal Zoological Society of Scotland’s Annual Review. On my first day, I spoke of Secondly, there is the respect Looking to the future, I encourage the privilege I felt to be your for and care of our animals. trustees, staff and members to President and that sentiment I have always recognised that retain their passion for our vision still remains. Therefore, there this is an essential part of our and to be ready, on occasion, to is a lump in my throat as I pen DNA and the exemplary record take measured risks. -

Biodiversity in Sub-Saharan Africa and Its Islands Conservation, Management and Sustainable Use

Biodiversity in Sub-Saharan Africa and its Islands Conservation, Management and Sustainable Use Occasional Papers of the IUCN Species Survival Commission No. 6 IUCN - The World Conservation Union IUCN Species Survival Commission Role of the SSC The Species Survival Commission (SSC) is IUCN's primary source of the 4. To provide advice, information, and expertise to the Secretariat of the scientific and technical information required for the maintenance of biologi- Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna cal diversity through the conservation of endangered and vulnerable species and Flora (CITES) and other international agreements affecting conser- of fauna and flora, whilst recommending and promoting measures for their vation of species or biological diversity. conservation, and for the management of other species of conservation con- cern. Its objective is to mobilize action to prevent the extinction of species, 5. To carry out specific tasks on behalf of the Union, including: sub-species and discrete populations of fauna and flora, thereby not only maintaining biological diversity but improving the status of endangered and • coordination of a programme of activities for the conservation of bio- vulnerable species. logical diversity within the framework of the IUCN Conservation Programme. Objectives of the SSC • promotion of the maintenance of biological diversity by monitoring 1. To participate in the further development, promotion and implementation the status of species and populations of conservation concern. of the World Conservation Strategy; to advise on the development of IUCN's Conservation Programme; to support the implementation of the • development and review of conservation action plans and priorities Programme' and to assist in the development, screening, and monitoring for species and their populations. -

Разведение Пальмового Жука-Фрегата Polposipus Herculeanus (Coleoptera, Tenebrionidae) В Рижском Зоосаду

162 РАЗВЕДЕНИЕ ПАЛЬМОВОГО ЖУКА-ФРЕГАТА POLPOSIPUS HERCULEANUS (COLEOPTERA, TENEBRIONIDAE) В РИЖСКОМ ЗООСАДУ И.В. Рома, А.В. Наполов Инсектарий Рижского Национального Зоологического сада, г. Рига, Латвия Статус в природе Чернотелка Polposipus herculeanus – это довольно крупный нелетаю- щий жук, ареал которого ограничен лесистыми участками острова Фрегат (Сейшельские острова), о чем говорит его английское название - Fregate Island palm beetle (пальмовый жук острова Фрегат). Этот вид включён в Красный Список Международного Союза охраны Природы (International Un- ion for the Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources – IUCN, или МСОП). Его статус обозначен как «критически угрожаемый» на основании очень сильного сокращения ареала, как предполагается, вследствие интродукции на остров серой крысы (Rattus norvegicus) в 1995г. К 2000г. крысы на острове были практически уничтожены. В 2001г. было отмечено увеличение числен- ности P. herculeanus на острове, но в 2002г. грибковая болезнь поразила большую часть деревьев Pterocarpus indicus, с которыми трофически и био- топически связан этот вид жуков. Множество погибших жуков было найдено на стволах больных деревьев, после чего было решено продолжить програм- му изучения и сохранения этого эндемичного вида чернотелок (Ferguson & Pearce-Kelly, 2004). Программа по размножению жука-фрегата в неволе В 1996г. представители Nature Protection Trust of Seychelles (NPTS) и BirdLife International (BI) обратились к специалистам The Invertebrate Conservation Unit (ICU) при Лондонском Зоологическом Обществе (Zoological Society of London - ZSL) с просьбой основать лабораторную куль- туру P. herculeanus. Программа начала работать в 1996г., когда в природе было собрано 47 жуков и перевезено в ZSL (Ferguson & Pearce-Kelly, 2004). С началом работы программы по размножению этого вида в неволе появилась надежда создать жизнеспособную резервную популяцию жуков, до того момента, пока остров не будет освобожден от крыс. -

London Zoo 6 Column Inventory.Pdf (629.47

ZSL London Zoo - Animal Inventory 2020 Group-managed species - births/deaths are recorded only when physically seen (i.e. not assumed). Therefore the * start- and end-of-year figures may not reconcile. Periodic census counts are taken to monitor the population & are recorded in ZIMS Group-managed species kept as colony - the group is kept as a single entity as births and deaths cannot be + monitered. Therefore the start- and end-of-year figures may not reconcile when colonies are split and/or merged. Any such activity is recorded in ZIMS m = male, f = female, unk = unknown ZSL LONDON ZOO Status at 01.01.2020 Births Arrivals Deaths Dispositions Status at 31.12.2020 m f unk m f unk m f unk m f unk m f unk m f unk Invertebrata Aurelia aurita * Moon jellyfish 0 0700 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0400 0 0 0 0 0150 Cassiopea sp. * Frilled upside-down jellyfish 0 0 3 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 50 0 0 0 Pachyclavularia violacea * Purple star coral 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 Tubipora musica * Organ-pipe coral 0 0 3 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 2 Pinnigorgia sp. * Sea fan 00200000000000000020 Lobophytum sp. * Leather coral 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 Sarcophyton sp. * Leathery soft coral 0 0 17 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 5 Sinularia sp. -

Zooquaria Issue 98

QUARTERLY PUBLICATION OF THE EUROPEAN ASSOCIATION OF ZOOS AND AQUARIA AUTUMNZ 2017OO QUARIAISSUE 98 FANTASTIC BEASTS THE FASCINATING WORLD OF INVERTEBRATE CONSERVATION Insects in the citadel INSIDE BESANCON'S STUNNING INSECTARIUM 1 1 Our duty of care ADDRESSING THE ISSUES OF INVERTEBRATE WELFARE Some passengers need a special travel agency Amsterdam Airport Frankfurt Airport ZooLogistics BV AnimalLogistics FRA GmbH Hoeksteen 155 Langer Kornweg 34 K 2132 MX Hoofddorp 65451 Kelsterbach [email protected] [email protected] www.zoologistics.com www.animallogistics.de +31 (0)20 / 31 65 090 +49 (0)6107 / 40 779 -21 1708-011 ADV OP A4.indd 6 23-08-17 14:29 Contents Zooquaria Autumn 2017 11 14 33 4 From the Director’s chair 19 Spider plan EAZA's Director pays tribute to the amazing work How Bristol Zoo is working to ensure breeding being done to support invertebrate conservation success for the Desertas wolf spider 5 Noticeboard 20 The snail’s story The latest news from EAZA Council After a 30-year breeding programme, the reintroduction of the Partula snail has begun 7 The rise of the invertebrates An update on the current activities of the Terrestrial 22 The insect man Invertebrate TAG Zooquaria talks to Mark Bushell of Bristol Zoo 8 The invertebrate 25 A vet’s life conservation challenge EAZA's Veterinary Advisor to the TITAG discusses the With millions of species in existence, how do we challenges of his role tackle the challenge of invertebrate conservation? 27 Marvellous monsters 11 Conservation data The EAZA TITAG and BIAZA -

Conservation Gains and Missed Opportunities 15 Years After Rodent Eradications in the Seychelles

J.E. Millett, W. Accouche, J. van de Crommenacker, M.A.J.A. van Dinther, A. de Groene, C.P. Havemann, T.A. Retief, J. Appoo and R.M. Bristol Millett, J.E.; W. Accouche, J. van de Crommenacker, M.A.J.A. van Dinther, A. de Groene, C.P. Havemann, T.A. Retief, J. Appoo and R.M. Bristol. Conservation gains and missed opportunities 15 years after rodent eradications in the Seychelles Conservation gains and missed opportunities 15 years after rodent eradications in the Seychelles J.E. Millett1, W. Accouche1, J. van de Crommenacker1,2, M.A.J.A. van Dinther2, A. de Groene3, C.P. Havemann4, T.A. Retief4, J. Appoo1 and R.M. Bristol5 1Green Islands Foundation, PO Box 246, Victoria, Mahé, Seychelles. <[email protected]>. 2Frégate Island Private, PO Box 330, Victoria, Mahé, Seychelles. 3WWF-Netherlands, Driebergseweg 10, 3708 JB Zeist, Netherlands. 4North Island, P.O. Box 1176, Victoria, Mahé, Seychelles. 5La Batie, Beau Vallon, Mahé, Seychelles. Abstract The Seychelles was one of the fi rst tropical island nations to implement island restoration resulting in biodiversity gain. In the 2000s a series of rat eradication attempts was undertaken in the inner Seychelles islands which had mixed results. Three private islands with tourist resorts successfully eradicated rats: Frégate (2000), Denis Island (2003) and North Island (2005). Frégate Island was successful with the fi rst eradication attempt whereas North and Denis Islands were initially unsuccessful, and both required second eradication operations. All three islands have developed conservation programmes including biosecurity, habitat rehabilitation, and species reintroductions, and have integrated nature into the tourism experience. -

Forestry Department Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations

Forestry Department Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations Forest Health & Biosecurity Working Papers Case Studies on the Status of Invasive Woody Plant Species in the Western Indian Ocean 5. Seychelles By C. Kueffer1 and P. Vos2 1. Geobotanical Institute, ETH (Federal Institute of Technology), Zurich, Switzerland 2. Forestry Section, Ministry of Environment & Natural Resources, Seychelles May 2004 Forest Resources Development Service Working Paper FBS/4-5E Forest Resources Division FAO, Rome, Italy Disclaimer The FAO Forestry Department Working Papers report on issues and activities related to the conservation, sustainable use and management of forest resources. The purpose of these papers is to provide early information on on-going activities and programmes, and to stimulate discussion. This paper is one of a series of FAO documents on forestry-related health and biosecurity issues. The study was carried out from November 2002 to May 2003, and was financially supported by a special contribution of the FAO-Netherlands Partnership Programme on Agro-Biodiversity. The designations employed and the presentation of material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Quantitative information regarding the status of forest resources has been compiled according to sources, methodologies and protocols identified and selected by the authors, for assessing the diversity and status of forest resources. For standardized methodologies and assessments on forest resources, please refer to FAO, 2003. -

UPDATE March/April200 1 School of Natural Resources and Environment Vol

UPDATE March/April200 1 School of Natural Resources and Environment Vol. 18 No. 2 THE UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN pages 29-60 30 Endangered Species and Peripheral Populations: Cause for Reflection A. Townsend Peterson 32 Special Series: Habitat Conservation Planning Part Ill: Incorporating Adaptive Management and the Precautionary Principle into HCP Design Gregory A. Thomas 41 Endangered Invertebrates: The Case for Greater Attention to Invertebrate Conservation Scott Hoffman Black, Matthew Shepard, and Melody Mackey Allen 50 The Impact of Communication Towers On Neotropical Songbird Populations Joanne M. Lopez 55 Marine Matters Marine Protected Areas: Examples from the San Juan Islands, Washington Terrie Klinger Opinion Endangered Species and Peripheral Populations: Cause for Reflection A. Townsend Peterson Natural History Museum and Biodiversity Research Center, The University of Kansas, Lawrence, Kansas 66045 USA Introduction cupido amaten'), and Florida Scrub-Jay populations of Northern Aplomado Endangered species lists constitute criti- (Aphelocorna coerulescens). These taxa Falcon would be regrettable, they al- cal foci of conservation attention. Spe- are clearly appropriate for inclusion in the naj)shave been marginal, and as such cies on such lists are given special atten- list, given that conservation efforts will likely have a tenuous hold on long-term tion in prioritizations for consenlation either prove successful in the United survival. Worse still. for species such (Peterson et al. 20001, with the Endan- States, or the taxon will be lost to extinc- as the Crested Caracara and the Fer- gered Species Act affording immediate tion. Another 19 of the endangered bird mginous Pygmy-Owl. although U.S. protection to areas known to hold popu- species, while not endemic to the populations are limited in distribution, lations of endangered species. -

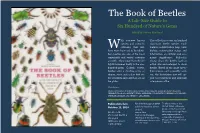

The Book of Beetles a Life-Size Guide to Six Hundred of Nature's Gems

The Book of Beetles A Life-Size Guide to Six Hundred of Nature's Gems Edited by Patrice Bouchard ith 350,000 known This collection covers six hundred species, and scientific significant beetle species. Each W estimates that mil- features a distribution map, basic lions more have yet to be identi- biology, conservation status, and fied, beetles are one of the most information on cultural and eco- remarkable and varied creatures nomic significance. Full-color on earth. They range from the de- photos show the beetles both at lightful summer firefly to the one- actual size and enlarged to show hundred-gram Goliath beetle. details. Based in the most up-to- Beetles offer a dazzling array of date science and accessibly writ- shapes, sizes, and colors that en- ten, the descriptive text will ap- tice scientists and collectors across peal to researchers and armchair the globe. coleopterists alike. Contributors: PATRICE BOUCHARD, YVES BOUSQUET, CHRISTOPHER CARLTON, MARIA LOURDES CHAMORRO, HERMES E. ESCALONA, ARTHUR V. EVANS, ALEXANDER S. KONSTANTINOV, RICHARD A. B. LESCHEN, STÉPHANE LE TIRANT, AND STEVEN W. LINGAFELTER. Publication date For a review copy or other To place orders in the October 15, 2014 publicity inquiries, please United States or Canada, contact: please contact your local $55.00, cloth Lauren Salas University of Chicago Press 978-0-226-08275-2 Promotions Manager, sales representative or contact the University of 656 pages University of Chicago Press, Chicago Press by phone at 2400 color plates [email protected] 773-702-0890 1-800-621-2736. 7 1/8 x 10 1/2 THE BOOK OF BEETLES THE BOOK OF BEETLES A LIFE-SIZE GUIDE TO SIX HUNDRED OF NATURE’S GEMS EDITOR PATRICE BOUCHARD CONTRIBUTORS PATRICE BOUCHARD, YVES BOUSQUET, CHRISTOPHER CARLTON, MARIA LOURDES CHAMORRO, HERMES E. -

Oil Spill Sensitivity of the Western Indian Ocean Islands: Coastal Data from the Comoros Islands, Madagascar, Mauritius, Reunion and the Seychelles

IV OIL SPILL SENSITIVITY OF THE WESTERN INDIAN OCEAN ISLANDS Coastal Data from the Comoros Islands, Madagascar, Mauritius, Reunion and the Seychelles Compiled by the World Conservation Monitoring Centre Editednby Dr. Edmund Green WORLD CONSERVATION MONITORING CENTRE Prepared by: Neil Cox, Edmund Green, Igor Lysenko, Balzhan Zhimbiev April 1998 The World Conservation Monitoring Centre (WCMC), based in Cambridge, UK is a joint-venture between the three partners in the World Conservation Strategy and its successor Caring For The Earth: IUCN - The World Conservation Union, UNEP - United Nations Environment Programme, and WWF - World Wide Fund for Nature. WCMC provides information services on conservation and sustainable use the world's living resources, and helps others to develop information systems of their own. Prepared with funding from AEA Technology pic WORLD CONSERVATION MONITORING CENTRE Copyright: World Conservation Monitoring Centre, Cambridge, UK. Copyright release: Reproduction of this publication for educational or other non- commercial purposes is authorised without prior permission from the copyright holders. Reproduction For resale or other commercial purpose is prohibited without the prior written permission of the copyright holders. Disclaimer: The designations of geographical entities and the presentation of material in this report do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever by WCMC and its collaborators and other participating organisations, concerning the legal or constitutional status of any country, territory, or area or of its authorities; or concerning the delineation of its frontiers or boundaries. Citation: WCMC, 1998. Oil spill sensitivity of the western indian ocean islands: coastal data from the Comoros islands, Madagascar, Mauritius, Reunion and the Seychelles. Edited by E.P.