Marlin 336 the Other Classic Backwoods Home Deer Rifle

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Curios Or Relics List — Update January 2008 Through June 2014 Section II — Firearms Classified As Curios Or Relics, Still Subject to the Provisions of 18 U.S.C

Curios or Relics List — Update January 2008 through June 2014 Section II — Firearms classified as curios or relics, still subject to the provisions of 18 U.S.C. Chapter 44, the Gun Control Act of 1968. • Browning, .22 caliber, semiautomatic rifles, Grade III, mfd. by Fabrique Nationale in Belgium. • Browning Arms Company, “Renaissance” engraved FN Hi Power pistols, caliber 9mm, manufactured from 1954 to 1976. • Browning FN, “Renaissance” engraved semiautomatic pistols, caliber .25. • Browning FN, “Renaissance” Model 10\71 engraved semiautomatic pistols, caliber .380. • Colt, Model Lawman Mark III Revolvers, .357 Magnum, serial number J42429. • Colt, Model U, experimental prototype pistol, .22 caliber semiautomatic, S/N U870001. • Colt, Model U, experimental prototype pistol, .22 caliber semiautomatic, S/N U870004. • Firepower International, Ltd., Gustloff Volkssturmgewehr, caliber 7.92x33, S/N 2. • Firepower International, Ltd., Gustloff Volkssturmgewehr, caliber 7.92x33, S/N 6. • Johnson, Model 1941 semiautomatic rifles, .30 caliber, all serial numbers, with the collective markings, “CAL. 30-06 SEMI-AUTO, JOHNSON AUTOMATICS, MODEL 1941, MADE IN PROVIDENCE. R.I., U.S.A., and Cranston Arms Co.” —the latter enclosed in a triangle on the receiver. • Polish, Model P64 pistols, 9 x 18mm Makarov caliber, all serial numbers. • Springfield Armory, M1 Garand semiautomatic rifle, .30 caliber, S/N 2502800. • Walther, Model P38 semiautomatic pistols, bearing the Norwegian Army Ordnance crest on the slide, 9mm Luger caliber, S/N range 369001-370000. • Walther, post World War II production Model P38- and P1-type semiautomatic pistols made for or issued to a military force, police agency, or other government agency or entity. • Winchester, Model 1894, caliber .30WCF, S/N 399704, with 16-inch barrel. -

Amoskeag Online #127 - August 2020 08/30/2020 12:15 PM EDT

Auction - Amoskeag Online #127 - August 2020 08/30/2020 12:15 PM EDT Lot Title/Description Lot Title/Description 2000 Special Order Marlin Model 1881 Lever Action Rifle 2003 Winchester Pre '64 Model 94 Carbine serial #14521, 40-60, 32'' extra-length octagon barrel with a good plus to serial #1543634, 32 Win. Spcl., 20'' barrel with a bright about excellent perhaps near very good bore which shows strong rifling its full-length bore. The barrel and magazine tube retaining about 92-95% original with some scattered oxidation and perhaps some light pitting. All the blue, the loss being some even wear at the muzzles and a bit of metal surfaces are a dull gunmetal gray with overall oxidation speckling, scattered light oxidation staining near the rear band. The bands some spots of active oxidation, and light pitting. The primary markings themselves show a bit of wear and the receiver has toned to gray on the on the barrel and the caliber marking are still legible. The checkered natural carry point at the belly, with some strong original blue on the flats walnut forend rates about good with the remnants of checkering and a and upper surface. The smooth American walnut buttstock rates very handful of light cracks or splits, the metal being proud of the wood. good with the expected light dings and handling marks from the years There is no buttstock, nor its screw present, and the tang shows two and two small notches in the point of comb. The long wood forend added holes. There is a bead front sight and a Rocky Mountain style shows a bit more wear and more handling marks as-expected, it rating rear present which partially obscures the barrel marking. -

A BILL to Regulate Assault Weapons, to Ensure That the Right to Keep and Bear Arms Is Not Unlimited, and for Other Purposes

SIL17927 S.L.C. 115TH CONGRESS 1ST SESSION S. ll To regulate assault weapons, to ensure that the right to keep and bear arms is not unlimited, and for other purposes. IN THE SENATE OF THE UNITED STATES llllllllll Mrs. FEINSTEIN (for herself, Mr. BLUMENTHAL, Mr. MURPHY, Mr. SCHU- MER, Mr. DURBIN, Mrs. MURRAY, Mr. REED, Mr. CARPER, Mr. MENEN- DEZ, Mr. CARDIN, Ms. KLOBUCHAR, Mr. WHITEHOUSE, Mrs. GILLI- BRAND, Mr. FRANKEN, Mr. SCHATZ, Ms. HIRONO, Ms. WARREN, Mr. MARKEY, Mr. BOOKER, Mr. VAN HOLLEN, Ms. DUCKWORTH, and Ms. HARRIS) introduced the following bill; which was read twice and referred to the Committee on llllllllll A BILL To regulate assault weapons, to ensure that the right to keep and bear arms is not unlimited, and for other purposes. 1 Be it enacted by the Senate and House of Representa- 2 tives of the United States of America in Congress assembled, 3 SECTION 1. SHORT TITLE. 4 This Act may be cited as the ‘‘Assault Weapons Ban 5 of 2017’’. 6 SEC. 2. DEFINITIONS. 7 (a) IN GENERAL.—Section 921(a) of title 18, United 8 States Code, is amended— SIL17927 S.L.C. 2 1 (1) by inserting after paragraph (29) the fol- 2 lowing: 3 ‘‘(30) The term ‘semiautomatic pistol’ means any re- 4 peating pistol that— 5 ‘‘(A) utilizes a portion of the energy of a firing 6 cartridge to extract the fired cartridge case and 7 chamber the next round; and 8 ‘‘(B) requires a separate pull of the trigger to 9 fire each cartridge. 10 ‘‘(31) The term ‘semiautomatic shotgun’ means any 11 repeating shotgun that— 12 ‘‘(A) utilizes a portion of the energy of a firing 13 cartridge to extract the fired cartridge case and 14 chamber the next round; and 15 ‘‘(B) requires a separate pull of the trigger to 16 fire each cartridge.’’; and 17 (2) by adding at the end the following: 18 ‘‘(36) The term ‘semiautomatic assault weapon’ 19 means any of the following, regardless of country of manu- 20 facture or caliber of ammunition accepted: 21 ‘‘(A) A semiautomatic rifle that has the capac- 22 ity to accept a detachable magazine and any 1 of the 23 following: 24 ‘‘(i) A pistol grip. -

30-30 Winchester 1 .30-30 Winchester

.30-30 Winchester 1 .30-30 Winchester .30-30 Winchester .30-30 cartridge (center) between 5.56×45mm NATO (.223 Remington), left, and 7.62×51mm NATO (.308 Winchester), right Type Rifle Place of origin United States Production history Designer Winchester Designed 1895 Manufacturer Winchester Produced 1895-Present Variants .25-35 Winchester, .219 Zipper, .30-30 Ackley Improved, 7-30 Waters Specifications Case type Rimmed, bottlenecked Bullet diameter .308 in (7.8 mm) Neck diameter .330 in (8.4 mm) Shoulder diameter .401 in (10.2 mm) Base diameter .422 in (10.7 mm) Rim diameter .506 in (12.9 mm) Rim thickness .063 in (1.6 mm) Case length 2.039 in (51.8 mm) Primer type large rifle Ballistic performance Bullet weight/type Velocity Energy 110 gr (7 g) FP 2,684 ft/s (818 m/s) 1,760 ft·lbf (2,390 J) 130 gr (8 g) FP 2,496 ft/s (761 m/s) 1,799 ft·lbf (2,439 J) 150 gr (10 g) FN 2,390 ft/s (730 m/s) 1,903 ft·lbf (2,580 J) 160 gr (10 g) cast LFN 1,616 ft/s (493 m/s) 928 ft·lbf (1,258 J) 170 gr (11 g) FP 2,227 ft/s (679 m/s) 1,873 ft·lbf (2,539 J) [1] Source(s): Hodgdon .30-30 Winchester 2 The .30-30 Winchester/.30 Winchester Center Fire/7.62×51mmR cartridge was first marketed in early 1895 for the Winchester Model 1894 lever-action rifle.[2] The .30-30 (thirty-thirty), as it is most commonly known, was the USA's first small-bore, sporting rifle cartridge designed for smokeless powder. -

Saturday April 28 , 2018

Saturday April 28th, 2018 Firearms, Sporting and Military Auction Being the Collection of Brian Govang with adtions. Firearms, Sporting and Military Auction Antique and Modern All Estate Fresh! Saturday April 28th, 2018 at 1:00pm Preview: Friday April 27th 10:00am-8:00pm 10:00am-1:00pm Day of Sale or by previous arrangement Daniel Buck Auctions Appraisals Fine Art Gallery 501 Lisbon Street Lisbon Falls, ME 04252 207-407-1444 Daniel Buck Soules – Auctioneer ME Lic. #AUC1591 NOTES CONDITIONS OF SALE The following “Conditions of Sale” are Daniel Buck’s and the Consignor’s Agreement with the Buyer relative to the prop- erty listed in the Auction Catalog. The glossary and all other contents of the catalog are subject to amendment by Daniel Buck by the posting of notices or by oral announcements made during the sale. All properties offered by Daniel Buck as agent for the Consignor unless the catalog indicates otherwise. By participating in a Daniel Buck sale, the Consignor, Bidder and Buyer agree to be bound by these Terms and Con- ditions. 1.) BEFORE THE SALE. Except for Online only auctions, all lots are available for inspection before and up to the begin- ning of the sale. Condition Reports are not included in the catalog description, but can be requested by contacting Dan- [email protected]. Any prospective bidder is encouraged to contact Daniel Buck Auctions for any information regarding the condition of any lot. Daniel Buck does not warrant the condition of any item. Any potential Buyer who is inter- ested in the condition of an item, are encouraged to contact Daniel Buck and, to the best of our ability, we will document for the prospective bidder the condition status of any lot the buyer is possibly interested in. -

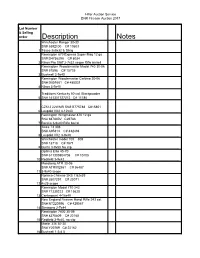

Description Notes

Hiller Auction Service DNR Firearm Auction 2017 Lot Number & Selling order Description Notes Winchester Ranger 30-30 SN# 5392100 C# 13603 1 Tasco 3x9x32 & Sling ___________________________________ Remington 870 Express Super Mag 12 ga SN# D473629A C# 8034 2 Nikon Pro Staff 2-7x32 scope Rifle barrell ___________________________________ Remingtom Woodsmaster Model 740 30-06 SN# 57598 C# 15735 3 Bushnell 3-9x40 ___________________________________ Remington Woodsmaster Carbine 30-06 SN# D801661 C# 480031 4 Nikon 3-9x40 ___________________________________ Traditions Kentucky 50 cal. Blackpowder 5 SN# 141301727212 C# 11186 ___________________________________ CZ512 22WMR SN# B775788 C#15851 6 Leupold VX2 4-12x40 ___________________________________ Remington Wingmaster 870 12 ga SN# 887840V C#9786 7 Barska 3-9x40 Rifle barrel ___________________________________ Tikka T3 308 SN# A95813 C# 432494 8 Leupold VX2 3-9x40 ___________________________________ Winchester model 100 308 SN# 13718 C# 7671 9 Burris 3-9x50 No clip ___________________________________ Optima Elite 45-70 SN# 611305904708 C# 10105 10 Redfield 3-9x42 ___________________________________ Mossberg ATR 30-06 SN# ATR082551 C# 36487 11 3-9x40 scope ___________________________________ Norinco Chinese SKS 7.62x39 SN# 2507297 C# 22071 12 4x25 scope ___________________________________ Remington Model 710 243 SN# 71339223 C# 15620 13 Centerpoint 4-16x40 ___________________________________ New England Firearm Handi Rifle 243 cal. SN# NT220996 C# 429567 14 Simmons 2-7x44 ___________________________________ -

Meet Adam Newman Md, Facog

POSTAL PATRON LOCAL BULK RATE U.S. POSTAGE Carrier Rt. Pre-Sort Clinton, MO The KAYO Permit No. 190 212 South Washington St., Clinton, Missouri 64735-0586 Wednesday, May 12, 2021 (660) 885-2281 FAX (660)885-2265 Gallery Three LLC Art Gallery on the downtown Clinton Square ‘17 PACIFICA LIMITED ‘15 SIERRA CREW 4WD ‘15 JOURNEY SE ‘12 DURANGO AWD PANORAMIC 5.3 V-8 LOCAL 47,000 137 S Washington TRADE MILES Clinton, MO 64735 Ready to save right away on your auto insurance? Combine Business Hours Current Event: affordable coverage from Leather, Panoramic Sunroof, Dual Power Seats, Heated/Cooled Seats, Low Miles, Best of Care! Local Trade, 4 Full Doors, Very Clean, Chrome 68,000 Miles, Med Blue Metallic, Local Trade, Power Local Trade, Low Miles, 7 Passenger, All Wheel Drive, Great Saturday May 15th @ 2:00 American Family Insurance with Overhead Sky Camera, Navigation, Lane Departure, Dual DVD’s Boards, Power Seat, Power Windows, Power Locks, 5.3 V-8, Trailer Tow Windows/Locks, Tilt, Cruise, Very Clean, Low Price Care, State Inspected, So Affordable, Chrome Boards Monday-Tuesday our free KnowYourDrive® program, Drawing class with and you’ll instantly get 10% off* Closed. Len Matthies – plus you could qualify for a free THE BEST CHROME BOARDS $13,388 $14,388 Travel Peace of Mind package* Wednesday-Friday with emergency roadside service, ‘11 EQUINOX LS ‘19 EQUINOX AWD ‘18 300 LIMITED 11:00-6:00. Gallery Three provides rental reimbursement and more. 2021 JEEP OFF COOLED an art space focused on Show off your safe driving habits STOCK LEASE LEATHER Saturday 10:00-2:00. -

Alar/Iii MODEL 1894

Q) r-. .:: (I) //fin"1t .D Q) 5 ~ U) ~ '5c:: ("00. :: ftI to .0 I CD .CI~ U fa WAIlIl~~lnll a:E '=' C :::J:" Q) s~~ ~ Q:J en...... >15 ~ ns M ,g :.eel)Q) cern rn ~ 5 ~ 0 iJj ~ - z Owner's Manual wU ~..,..,..,..,~o ~ a.. < ~..,..,""> Z~ Qj Q) WARNING: Do not use Blazer "C Q) c 0 brand ammunition in this rifte. The ;:~ (J) ~ () desi9n is not compatible with the 0 Om rn a. Manln feeding system, and may ~ ..r:: '0Q) result in live rounds inadvertently u. u N Alar/Iii ..... (ij~ remaining in the magazine. O.!!? . :J L w£ 0)c ,,2iE Cia.. §. !:: en- >-~ . ~C/)OI~~§ !;i E . 0 UrnQ) <3 _!- glJ:tili u:~~ ~2 rn :Ejii ann~ MODEL 1894 -;.c:: ~o ~ s-g-g-g I-c:::u ;~g.~~~ nI ~ cuCI:EEE i: :; ;fi-gROO;; "w rno. ~ .. ~ if) ~ ~ ,.... ~ ~m a:: ex:a: COWBOY II U~o >, (j)en L() Q) :; C:;(J) C Q) 0 >-S'", S2. rn .,>'T::III)Q) Z ..... -0 rn g ~~ \0- "C Q) 1:) - o::r: iJj ~ ~,~ < ~ m ~="1S ,,<:; LEVER ACTION RIFLE ro ~ ~.=~a."C<ce ~.E~ ~ :J>, c::: : =~~~!C; c::: .c ~ .! ~ eo!: fa .£ Z ,Q 357 MAGNUM ..g:E :: ~ E ~ ~ ~ ~ Et~ < u::: 0 ~o -0 ;'fi~€~~g' (J) 2~U c::: ",, ~ ~~~~~~~ IMPORTANT e" 'd' -0) .Q -§ ~ < o.~ 0) c::rn CL This manual contains operating, care and maintenance instructions. To ::::> ;: >,'~ co ~~ a. ID (0-c: it! assure safe operation, any user of this firearm must read this manual c E ..... O.!!? Q) ., .~ C Q)CJ Q) : ~'~ c: VI CD it! 0') carefully. -

Curios Or Relics List — January 1972 Through April 2018 Dear Collector

Curios or Relics List — January 1972 through April 2018 Dear Collector, The Firearms and Ammunition Technology Division (FATD) is pleased to provide you with a complete list of firearms curios or relics classifications from the previous editions of the Firearms Curios or Relics (C&R) List, ATF P 5300.11, combined with those made by FATD through April 2018. Further, we hope that this electronic edition of the Firearms Curios or Relics List, ATF P 5300.11, proves useful for providing an overview of regulations applicable to licensed collectors and ammunition classified as curios or relics. Please note that ATF is no longer publishing a hard copy of the C&R List. Table of Contents Section II — Firearms classified as curios or relics, still subject to the provisions of 18 U.S.C. Chapter 44, the Gun Control Act of 1968. ............................................................................................1 Section III — Firearms removed from the provisions of the National Firearms Act and classified as curios or relics, still subject to the provisions of 18 U.S.C. Chapter 44, the Gun Control Act of 1968. .......................................................................................................................................................23 Section IIIA —Firearms manufactured in or before 1898, removed from the provisions of the National Firearms Act and classified as antique firearms not subject to the provisions of 18 U.S.C. Chapter 44, the Gun Control Act of 1968. ..............................................................................65 Section IV — NFA firearms classified as curios or relics, still subject to the provisions of 26 U.S.C. Chapter 53, the National Firearms Act, and 18 U.S.C. Chapter 44, the Gun Control Act of 1968. .......................................................................................................................................................83 Section II — Firearms classified as curios or relics, still subject to the provisions of 18 U.S.C. -

Download AR Dope Bag August 2001: Ed Brown Savanna Rifle

Ed Brown ost custom rifle- That means Brown actions and smiths begin with rifles are built one at a time on Savanna Rifle Mfactory bolt-actions computer numeric controlled that they rework according to machining centers to customer their philosophies. For world- order with each rifle personal- class shooter and custom gun- ly built and tested by Ed or one smith Ed Brown, that was of his two sons. The result is the unacceptable as he could not Ed Brown Model 702 action control the quality of mass- that Brown offers as the basic produced factory actions. For building block for five models. that reason, Brown set out to The NRA Technical Staff manufacture his own bolt- recently received an Ed Brown action that combines leading- Savanna model in .300 Win. edge manufacturing tech- Mag. for test and evaluation. niques and proven features The Brown Savanna rifle is 1 with old-world craftsmanship. a classically styled, 7 ⁄2-lb. SHOOTING RESULTS Ed Brown elected to manufac- .300 Win. Mag. Vel. @ 15' Energy Recoil Smallest Largest Average ture his own rifle actions, combining Cartridge (f.p.s.) (ft.-lbs.) (ft.-lbs.) (inches) (inches) (inches) old world craftsmanship with modern manu- Federal P300WT4 3125 Avg. 3,150 24.5 0.85 1.06 0.92 facturing techniques. They are offered in short 150-gr. TBBC 27 Sd or long lengths with right- or left-hand operation. Hornady 8202 2923 Avg. 3,131 25.9 0.61 1.08 0.84 165-gr. BTSPIL 20 Sd sporter intended for 26" stainless or carbon steel Winchester X30WM2 2861 Avg. -

Quible Retirement RANCH AUCTION

Quible Retirement CBA RANCH AUCTION Saturday, September 16, 2017, 10:00 AM (MST) 6 Miles East of Merriman, NE; Mile Marker 141 (34305 US Hwy 20) Watch for CBA signs Equipment and Ranch JD 7410 Tractor (well cared for excellent condition) power quad transmission 3pt. 2610 hrs. new tires and duals with 740 JD loader • Big Dog 8 yrd. Dirt scrapper • New Holland Tedder Rake • 8’ 3 point straw crimper • New 95 Chevy pickup box (short) • Semi trailer 40’ (no title) • Storage container 40’ • Bale processor • JD 3 point quick hitch • Bale buster • 24’ Gooseneck 2 axle flatbed (Sandhills Manufacturing) • Rowse 2 bale fork • JD 95 3pt. 9 ½ ft. blade • Bison 3 shank ripper • 3pt. Post digger •Quick attach skidster post driver (near new) • Pickup box trailer • 1995 Feightliner tractor truck (has been tipped over) • 3 Horse gooseneck slant tandem axle trailer • 15 ½ ft. Flat bed trailer all steel tandem axle bumper pull hitch w/fenders • 3 Point hydraulic bale feeder (works good) Electric gas pump • Witte generator • 3 hp Electric motor • Chevy 350 motor with 4 bolt main • New in box 2450 hydro Shop and Misc. stat motor drive • 300 ft. discharge hose pump • Warn chemical equip. co. fire fighting rig for pickup (400 gal., Honda motor, 580 psi, 100ft. hose) • 1998 Warrior 193 boat & trailer w/135 Mercury optimax & Mercury 9.9 kicker • Hub for 535 baler • Vaccine guns • Metal tractor seat • Honda eg 3500 generator • used JD tractor seat from 7410 tractor • (2) garden corn planters • Fishing rods • Buckets of bolts • Craftsman 10” bench grinder • (2) 500 gal. -

Curios Or Relics List — Update January 2008 Through December 2008

Curios or Relics List — Update January 2008 through December 2008 Firearms automatically attain curio or relic (C&R) status when they are 50 years old. Any firearm that is at least 50 years old, and in its original configuration, would qualify as a C&R firearm. It is not necessary for such firearms to be listed in ATF’s C&R list. However, if your C&R item is regulated under the National Firearms Act (NFA) and you desire removal from the provisions of the NFA, you must submit the firearm to the Firearms Technology Branch for evaluation and a formal classification. Section III — Firearms removed from the provisions of the National Firearms Act and classified as curios or relics, still subject to the provisions of 18 U.S.C. Chapter 44, the Gun Control Act of 1968. A.H. Fox Company, “Diana” shotgun engraving sample, S/N 19522, with 4 ¾-inch barrels and no internal working parts Iver Johnson Arms & Cycle Works, single-barreled cut-away shotgun, S/N 64 Mannlicher, m/01, m/02, and m/06 pistol-carbines with factory-produced, fixed rifle-type shoulder stock and forearm and 11 ¾ long barrels in calibers 7.65mm Mannlicher, 9mm Parabellum, and 7.63mm Mauser Marlin, Model 1893, caliber .32-40, S/N C1417, with 15-inch barrel Marlin, Model 1894, caliber .44-40, S/N D7720, with 15-inch barrel Marlin, Model 1894, caliber .44-40, S/N 292933, with 15-inch barrel Marlin, Model 1894, caliber .44-40, S/N 426868, with 15-inch barrel Marlin, Model 94 carbine, caliber .44, S/N 422706, with 15-inch barrel Marlin Firearms, Model 1889, factory cut-away rifle, S/N 29533, with a 5-inch barrel Marlin Firearms, Model 1889, factory cut-away rifle, S/N 23, with a 4-½ inch barrel, no magazine tube Remington Keen Prototype Bolt-Action Rifle, S/N 4, with 4-inch barrel Smith & Wesson, Model 1950, caliber .44 S&W Special, serial number S106284, with factory-fitted 6.5 inch barrel; and with red post front sight, bright blue and nickel two- tone finish, target hammer and trigger, and birds-eye maple grips; made as a special one- of-a-kind factory presentation model for Congressman Cecil B.