444 Marlin- America's Most Versatile Big-Bore Part I Marshall Stanton on 2001-06-27

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Marlin 336 the Other Classic Backwoods Home Deer Rifle

Marlin 336 The other classic backwoods home deer rifle By Massad Ayoob In the March/April 2005 issue of Backwoods Home Magazine, this space was devoted to the “Winchester ‘94: the Classic Backwoods Home Deer Rifle.” And you know, even when I was writing that paean to the lever-action .30-30 that sold over five million units since the year 1894, I knew that I’d have to follow up with an article on the other such deer rifle, Marlin’s Model 336. Marlin introduced their Model 1893 rifle in the eponymous year, initially in old black powder calibers like the .32-40 and .38-55, but soon chambered for the .30-30 Winchester round. Some 900,000 of these guns were made between then and 1935, when the company replaced it with their sleeker Model 36. Where Winchester emphasized a lean, mean straight- stock design with a slim, spare fore-end, the Marlin had a pistol grip style stock with its lever loop bent accordingly, and a fuller fore-end. These attributes were carried into the newer gun, destined to be their longest-lived deer rifle: the Model 336, introduced in 1948 and still Marlin’s most popular hunting rifle. The rest, as the saying goes, is history. At the SHOT Show—it stands for Shooting, Hunting, and Outdoor Trade, the largest trade show in the firearms industry—in Las Vegas in January, 2005, I had the privilege of looking over a handsomely engraved rifle that was Marlin’s four millionth Model 336. From the early days, the Marlin’s solid frame with ejection to the right side (instead of out the top of the mechanism, as with the Winchester) was one of its distinguishing features. -

Marlin Model 56 Owners Manual

Marlin Model 56 Owners Manual Vintage Marlin Front Sight Hood 39a 56 336 788. 15.95. View Details Marlin Model 39a Lever Action Rifle Owners Manual Free Shipping. 8.84. View Details. Original Marlin Model 56 Levermatic 22LR Breech Bolt with Extractors #1508006. $27.16 Marlin 56 Levermatic Factory Owners Manual Reproduction. I have a 1955 model 56 rifle. I have looked through the threads here, but have yet to find a manual or disassembly instructions. You Tube Levermatic Owners ? Marlin Model 39a Lever Action Rifle Owners Manual Free Shipping. $8.84. Was: $9.50 Bersa Black Pistol Grips - O56 - Used Gun Parts & Accessories. $11.99. Firearms Manuals. Browning Hi-Power (Owner) · Browning Century French MA36, 49, 56 Rifles Colt Government MKIV Series 70 Model O 1970A1. MidwayUSA carries a full line of Marlin products from all the major brands. MidwayUSA is superstore of gear at great prices and same day. Marlin Model 56 Owners Manual Read/Download Marlin model 39a find the better deals on AuctionsOmatic. Vintage Marlin Front Sight Hood 39A ,56 ,336 ,788. XS Marlin 336 Front Sight. $15.95 MARLIN 39 39A 39M Lever Action.22 Cal Rifle OWNERS MANUAL. marlin model 39a. Frank Cahr PM 9 with case, manual, 5 mags $650 520 222 2554 Greg Marlin Model 60 rifle with Simmons scope and case $175 256 4739 with trailer, only in water 4 times (2nd owner), with sales asking $800 with title, 1962 Midget Frank FREE Blind Cane 56” , looking for swag lamp, for sale doggie crate 24” x 18”. hard to find vintage Redfield scope base for Marlin Model 56, 57, 57M Levermatic. -

Owner's Manual

Owner’s Manual IMPORTANT! Page 2 ......The Ten Commandments of This manual contains operating, care, and Firearm Safety maintenance instructions. To assure safe Page 7 .... Important Parts of the operation, any user of this firearm must read and understand this manual before using the Firearm firearm. Failure to follow the instructions and heed the Page 10 .... Safe Firearm Handling warnings in this manual can cause property damage, Page 12 .... To Load the Firearm personal injury, and/or death. Page 14 .... To Unload the Firearm This manual should always accompany this firearm, and Page 16 .... Lubrication and Maintenance be transferred with it upon change of ownership. Page 20 .... To Function Test the Firearm WARNING! Keep this firearm out of the reach of children, Page 25 .... Parts List unauthorized individuals, and others unfamiliar with safe Page 28 .... How to Obtain Parts and handing of firearms. Service r4_e7456rem_Q8:Marlin XT-Series Firearms.qxd 1/26/12 10:46 PM Page 3 A Tradition of Performance and Safety. • Let Your rifle has been made to Marlin’s strict standards of safety and reliability. It has been proof tested that with a high pressure load, function fired, and checked for accuracy at the factory. Built with tradition a str and engineered to last, your rifle is the product of over 135 years of Marlin technology. load in a Before You Use This Firearm. • Ce It is very important that you read and understand this manual before using your new rifle. Warnings thor should be read and heeded carefully. Always follow the “Ten Commandments of Firearm Safety,” list- as c ed in this manual. -

30-30 Winchester 1 .30-30 Winchester

.30-30 Winchester 1 .30-30 Winchester .30-30 Winchester .30-30 cartridge (center) between 5.56×45mm NATO (.223 Remington), left, and 7.62×51mm NATO (.308 Winchester), right Type Rifle Place of origin United States Production history Designer Winchester Designed 1895 Manufacturer Winchester Produced 1895-Present Variants .25-35 Winchester, .219 Zipper, .30-30 Ackley Improved, 7-30 Waters Specifications Case type Rimmed, bottlenecked Bullet diameter .308 in (7.8 mm) Neck diameter .330 in (8.4 mm) Shoulder diameter .401 in (10.2 mm) Base diameter .422 in (10.7 mm) Rim diameter .506 in (12.9 mm) Rim thickness .063 in (1.6 mm) Case length 2.039 in (51.8 mm) Primer type large rifle Ballistic performance Bullet weight/type Velocity Energy 110 gr (7 g) FP 2,684 ft/s (818 m/s) 1,760 ft·lbf (2,390 J) 130 gr (8 g) FP 2,496 ft/s (761 m/s) 1,799 ft·lbf (2,439 J) 150 gr (10 g) FN 2,390 ft/s (730 m/s) 1,903 ft·lbf (2,580 J) 160 gr (10 g) cast LFN 1,616 ft/s (493 m/s) 928 ft·lbf (1,258 J) 170 gr (11 g) FP 2,227 ft/s (679 m/s) 1,873 ft·lbf (2,539 J) [1] Source(s): Hodgdon .30-30 Winchester 2 The .30-30 Winchester/.30 Winchester Center Fire/7.62×51mmR cartridge was first marketed in early 1895 for the Winchester Model 1894 lever-action rifle.[2] The .30-30 (thirty-thirty), as it is most commonly known, was the USA's first small-bore, sporting rifle cartridge designed for smokeless powder. -

BOLT ACTION RIMFIRE RIFLE LIST BOLT PARTS PART NUMBER PART *Restricted Availability—Part Sent to Qualified Gunsmith Only

Owner's Manual BOLTBOLT ACTIONACTION RimfireRimfire RifleRifle IMPORTANT Never attempt to load your rifle with ammunition that does not meet the cartridge designation stamped on the barrel. If this rifle is chambered for either 22 Winchester Magnum Rimfire or 17 Hornady Magnum Rimfire, do not attempt to use 22 Short, Long or Long Rifle cartridges. IMPORTANT This manual contains operating, care and maintenance instructions. To assure safe operation, any user of this firearm must read this manual carefully. Failure to follow the instructions and warnings in this manual can cause accidents resulting in injury or death. This manual should always accompany this firearm, and be transferred with it upon change of ownership. The warranty card bound into this manual must be filled out and mailed within 10 days of purchase. WARNING: KEEP THIS FIREARM OUT OF THE REACH OF CHILDREN, UNAUTHORIZED INDIVIDUALS, AND OTHERS UNFAMILIAR WITH THE SAFE HANDLING OF FIREARMS. COMES WITH MARLINʼS 5-YEAR WARRANTY How Your Rifle is Made Your rifle has been made to Marlin’s strictest standards of safety and reliability. It has been proof tested with a high pressure load, function fired, and checked for accuracy at the factory. Built with tradition and engineered to last, your rifle is the product of over 135 years of Marlin technology. Before You Use This Firearm It is very important that you read and understand this manual before using your new rifle. Warnings should be read and heeded carefully. Also follow the safety rules listed in “Marlin’s Guide to Gun Safety”, printed on this page. • WARNING: Marlin firearms are designed and manufactured to handle standard factory- loaded ammunition which conforms to SAAMI (Sporting Arms and Ammunition Manufacturers’ Institute Inc.) standards with dependability and safety. -

Model 1894 Centerfire Lever Action Rifles

Owner's Manual CENTERFIRE LEVER ACTION RIFLES Model 1894 IMPORTANT This manual contains operating, care and maintenance instructions. To assure safe operation, any user of this firearm must read this manual carefully. Failure to follow the instructions and warnings in this manual can cause accidents resulting in injury or death. This manual should always accompany this firearm, and be transferred with it upon change of ownership. The warranty card bound into this manual must be filled out and mailed within 10 days of purchase. WARNING: KEEP THIS FIREARM OUT OF THE REACH OF CHILDREN, UNAUTHORIZED INDIVIDUALS, AND OTHERS UNFAMILIAR WITH THE SAFE HANDLING OF FIREARMS. COMES WITH MARLINʼS 5-YEAR WARRANTY How Your Rifle is Made Your rifle has been made to Marlin’s strictest standards of safety and reliability. It has been proof tested with a high pressure load, function fired, and checked for accuracy at the factory. Built with tradition and engineered to last, your rifle is the product of over 135 years of Marlin technology. Before You Use This Firearm It is very important that you read and understand this manual before using your new rifle. Warnings should be read and heeded carefully. Also follow the safety rules listed in “Marlin’s Guide to Gun Safety”, printed on this page. • WARNING: Marlin firearms are designed and manufactured to handle standard factory- loaded ammunition which conforms to SAAMI (Sporting Arms and Ammunition Manufacturers’ Institute Inc.) standards with dependability and safety. Due to the many bullet and load options available, the element of judgement involved, the skill required, and the fact that serious injuries have resulted from dangerous handloads, Marlin does not make any recommendations with regard to handloaded ammunition. -

Marlin XT-22 / XT-17 Owners Manual

0wner’s Manual Instruction Book for: TM XT Series Bolt Action Rimfire Rifles Page 2 ....... The Ten Commandments IMPORTANT! of Firearm Safety Page 7 ....... Important Parts of This manual contains operating, care, and the Firearm maintenance instructions. To assure safe operation, any user of this firearm must Page 11 ....... To Load the Firearm read and understand this manual before using the Page 14 ....... To Unload the Firearm firearm. Failure to follow the instructions and heed the warnings in this manual can cause property damage, Page 17 ....... Lubrication and Maintenance personal injury, and/or death. Page 21 ....... To Function Test the This manual should always accompany this firearm, and Firearm be transferred with it upon change of ownership. Page 24 ....... Parts List WARNING! Keep this firearm out of the reach of children, Page 28 ....... How to Obtain Parts unauthorized individuals, and others unfamiliar with safe and Service handing of firearms. A Tradition of Performance and Safety. Your rifle has been made to Marlin’s strict standards of safety and reliability. It has been proof test- ed with a high pressure load, function fired, and checked for accuracy at the factory. Built with tra- dition and engineered to last, your rifle is the product of over 135 years of Marlin technology. Before You Use This Firearm. It is very important that you read and understand this manual before using your new rifle. Warnings should be read and heeded carefully. Always follow the “Ten Commandments of Firearm Safety,” list- ed in this manual. Failure to follow these rules, warnings, or other instructions in this manual, can result in personal injury, property damage or death. -

Saturday April 28 , 2018

Saturday April 28th, 2018 Firearms, Sporting and Military Auction Being the Collection of Brian Govang with adtions. Firearms, Sporting and Military Auction Antique and Modern All Estate Fresh! Saturday April 28th, 2018 at 1:00pm Preview: Friday April 27th 10:00am-8:00pm 10:00am-1:00pm Day of Sale or by previous arrangement Daniel Buck Auctions Appraisals Fine Art Gallery 501 Lisbon Street Lisbon Falls, ME 04252 207-407-1444 Daniel Buck Soules – Auctioneer ME Lic. #AUC1591 NOTES CONDITIONS OF SALE The following “Conditions of Sale” are Daniel Buck’s and the Consignor’s Agreement with the Buyer relative to the prop- erty listed in the Auction Catalog. The glossary and all other contents of the catalog are subject to amendment by Daniel Buck by the posting of notices or by oral announcements made during the sale. All properties offered by Daniel Buck as agent for the Consignor unless the catalog indicates otherwise. By participating in a Daniel Buck sale, the Consignor, Bidder and Buyer agree to be bound by these Terms and Con- ditions. 1.) BEFORE THE SALE. Except for Online only auctions, all lots are available for inspection before and up to the begin- ning of the sale. Condition Reports are not included in the catalog description, but can be requested by contacting Dan- [email protected]. Any prospective bidder is encouraged to contact Daniel Buck Auctions for any information regarding the condition of any lot. Daniel Buck does not warrant the condition of any item. Any potential Buyer who is inter- ested in the condition of an item, are encouraged to contact Daniel Buck and, to the best of our ability, we will document for the prospective bidder the condition status of any lot the buyer is possibly interested in. -

Firearms Bibliography

Firearms Bibliography While we hope you find this bibliography helpful, it is far from an exhaustive firearms reading list. Additional sources of information will often be listed in the bibliographies found in these books. * Denotes titles that may be available for purchase through the Buffalo Bill Center of the West’s Museum Store. To find out, visit https://store.centerofthewest.org/ or call 800.533.3838. General Reference and Histories Barnes, Frank C. Cartridges of the World, 11th Edition. Edited by Stan Skinner. Iola, WI: Krause Publications, 2006. Blackmore, Howard. Guns and Rifles of the World. New York: Viking Press, 1965. Bogdanovic, Branko, & Valencak, Ivan. The Great Century of Guns. New York: Gallery Guns, 1986. Ezell, Edward C. Small Arms of the World. 12th Edition. Harrisburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 1983. *Flayderman, Norm. Flayderman’s Guide to Antique American Firearms and Their Values, 9th edition. Northbrook, IL: Krause Publications, 2007. Greener, W.W. The Gun and Its Development. Secaucus, NJ: Chartwell Books, 1988. Hogg, Ian. The Complete Illustrated Encyclopedia of the World's Firearms. New York: A & W Publishers, 1978. Hogg, Ian. Handguns and Rifles: The Finest Weapons from Around the World. London: Lyons Press, 1997. Fadala, Sam. The Complete Black Powder Handbook, 4th Edition. Iola, WI: Krause Publications, 2001. *Fjestad, S.P. Blue Book of Gun Values. (Updated once a year.) Minneapolis, MN: Blue Book Publishing. Krasne, Jerry A. Encyclopedia and Reference Catalog for Auto Loading Guns.San Diego, CA: Triple K Manufacturing, 1989. Mathews, J. Howard. Firearms Identification. (Three volume set.) Springfield, IL: Charles C. Thomas, 1973. (First printed in 1962.) Philip, Craig, The World's Great Small Arms. -

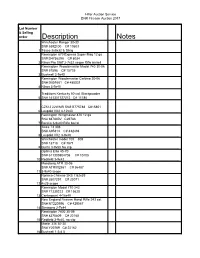

Description Notes

Hiller Auction Service DNR Firearm Auction 2017 Lot Number & Selling order Description Notes Winchester Ranger 30-30 SN# 5392100 C# 13603 1 Tasco 3x9x32 & Sling ___________________________________ Remington 870 Express Super Mag 12 ga SN# D473629A C# 8034 2 Nikon Pro Staff 2-7x32 scope Rifle barrell ___________________________________ Remingtom Woodsmaster Model 740 30-06 SN# 57598 C# 15735 3 Bushnell 3-9x40 ___________________________________ Remington Woodsmaster Carbine 30-06 SN# D801661 C# 480031 4 Nikon 3-9x40 ___________________________________ Traditions Kentucky 50 cal. Blackpowder 5 SN# 141301727212 C# 11186 ___________________________________ CZ512 22WMR SN# B775788 C#15851 6 Leupold VX2 4-12x40 ___________________________________ Remington Wingmaster 870 12 ga SN# 887840V C#9786 7 Barska 3-9x40 Rifle barrel ___________________________________ Tikka T3 308 SN# A95813 C# 432494 8 Leupold VX2 3-9x40 ___________________________________ Winchester model 100 308 SN# 13718 C# 7671 9 Burris 3-9x50 No clip ___________________________________ Optima Elite 45-70 SN# 611305904708 C# 10105 10 Redfield 3-9x42 ___________________________________ Mossberg ATR 30-06 SN# ATR082551 C# 36487 11 3-9x40 scope ___________________________________ Norinco Chinese SKS 7.62x39 SN# 2507297 C# 22071 12 4x25 scope ___________________________________ Remington Model 710 243 SN# 71339223 C# 15620 13 Centerpoint 4-16x40 ___________________________________ New England Firearm Handi Rifle 243 cal. SN# NT220996 C# 429567 14 Simmons 2-7x44 ___________________________________ -

Meet Adam Newman Md, Facog

POSTAL PATRON LOCAL BULK RATE U.S. POSTAGE Carrier Rt. Pre-Sort Clinton, MO The KAYO Permit No. 190 212 South Washington St., Clinton, Missouri 64735-0586 Wednesday, May 12, 2021 (660) 885-2281 FAX (660)885-2265 Gallery Three LLC Art Gallery on the downtown Clinton Square ‘17 PACIFICA LIMITED ‘15 SIERRA CREW 4WD ‘15 JOURNEY SE ‘12 DURANGO AWD PANORAMIC 5.3 V-8 LOCAL 47,000 137 S Washington TRADE MILES Clinton, MO 64735 Ready to save right away on your auto insurance? Combine Business Hours Current Event: affordable coverage from Leather, Panoramic Sunroof, Dual Power Seats, Heated/Cooled Seats, Low Miles, Best of Care! Local Trade, 4 Full Doors, Very Clean, Chrome 68,000 Miles, Med Blue Metallic, Local Trade, Power Local Trade, Low Miles, 7 Passenger, All Wheel Drive, Great Saturday May 15th @ 2:00 American Family Insurance with Overhead Sky Camera, Navigation, Lane Departure, Dual DVD’s Boards, Power Seat, Power Windows, Power Locks, 5.3 V-8, Trailer Tow Windows/Locks, Tilt, Cruise, Very Clean, Low Price Care, State Inspected, So Affordable, Chrome Boards Monday-Tuesday our free KnowYourDrive® program, Drawing class with and you’ll instantly get 10% off* Closed. Len Matthies – plus you could qualify for a free THE BEST CHROME BOARDS $13,388 $14,388 Travel Peace of Mind package* Wednesday-Friday with emergency roadside service, ‘11 EQUINOX LS ‘19 EQUINOX AWD ‘18 300 LIMITED 11:00-6:00. Gallery Three provides rental reimbursement and more. 2021 JEEP OFF COOLED an art space focused on Show off your safe driving habits STOCK LEASE LEATHER Saturday 10:00-2:00. -

Curios Or Relics List — January 1972 Through April 2018 Dear Collector

Curios or Relics List — January 1972 through April 2018 Dear Collector, The Firearms and Ammunition Technology Division (FATD) is pleased to provide you with a complete list of firearms curios or relics classifications from the previous editions of the Firearms Curios or Relics (C&R) List, ATF P 5300.11, combined with those made by FATD through April 2018. Further, we hope that this electronic edition of the Firearms Curios or Relics List, ATF P 5300.11, proves useful for providing an overview of regulations applicable to licensed collectors and ammunition classified as curios or relics. Please note that ATF is no longer publishing a hard copy of the C&R List. Table of Contents Section II — Firearms classified as curios or relics, still subject to the provisions of 18 U.S.C. Chapter 44, the Gun Control Act of 1968. ............................................................................................1 Section III — Firearms removed from the provisions of the National Firearms Act and classified as curios or relics, still subject to the provisions of 18 U.S.C. Chapter 44, the Gun Control Act of 1968. .......................................................................................................................................................23 Section IIIA —Firearms manufactured in or before 1898, removed from the provisions of the National Firearms Act and classified as antique firearms not subject to the provisions of 18 U.S.C. Chapter 44, the Gun Control Act of 1968. ..............................................................................65 Section IV — NFA firearms classified as curios or relics, still subject to the provisions of 26 U.S.C. Chapter 53, the National Firearms Act, and 18 U.S.C. Chapter 44, the Gun Control Act of 1968. .......................................................................................................................................................83 Section II — Firearms classified as curios or relics, still subject to the provisions of 18 U.S.C.