Application to Register Land at Two Fields, Westbere As a New Village

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kent Archæological Society Library

http://kentarchaeology.org.uk/research/archaeologia-cantiana/ Kent Archaeological Society is a registered charity number 223382 © 2017 Kent Archaeological Society KENT ARCILEOLOGICAL SOCIETY LIBRARY SIXTH INSTALMENT HUSSEY MS. NOTES THE MS. notes made by Arthur Hussey were given to the Society after his death in 1941. An index exists in the library, almost certainly made by the late B. W. Swithinbank. This is printed as it stands. The number given is that of the bundle or box. D.B.K. F = Family. Acol, see Woodchurch-in-Thanet. Benenden, 12; see also Petham. Ady F, see Eddye. Bethersden, 2; see also Charing Deanery. Alcock F, 11. Betteshanger, 1; see also Kent: Non- Aldington near Lympne, 1. jurors. Aldington near Thurnham, 10. Biddend.en, 10; see also Charing Allcham, 1. Deanery. Appledore, 6; see also Kent: Hermitages. Bigge F, 17. Apulderfield in Cudham, 8. Bigod F, 11. Apulderfield F, 4; see also Whitfield and Bilsington, 7; see also Belgar. Cudham. Birchington, 7; see also Kent: Chantries Ash-next-Fawkham, see Kent: Holy and Woodchurch-in-Thanet. Wells. Bishopsbourne, 2. Ash-next-Sandwich, 7. Blackmanstone, 9. Ashford, 9. Bobbing, 11. at Lese F, 12. Bockingfold, see Brenchley. Aucher F, 4; see also Mottinden. Boleyn F, see Hever. Austen F (Austyn, Astyn), 13; see also Bonnington, 3; see also Goodneston- St. Peter's in Tha,net. next-Wingham and Kent: Chantries. Axon F, 13. Bonner F (Bonnar), 10. Aylesford, 11. Boorman F, 13. Borden, 11. BacIlesmere F, 7; see also Chartham. Boreman F, see Boorman. Baclmangore, see Apulderfield F. Boughton Aluph, see Soalcham. Ballard F, see Chartham. -

KENT. Canterbt'ry, 135

'DIRECTORY.] KENT. CANTERBt'RY, 135 I FIRE BRIGADES. Thornton M.R.O.S.Eng. medical officer; E. W. Bald... win, clerk & storekeeper; William Kitchen, chief wardr City; head quarters, Police station, Westgate; four lad Inland Revilnue Offices, 28 High street; John lJuncan, ders with ropes, 1,000 feet of hose; 2 hose carts & ] collector; Henry J. E. Uarcia, surveyor; Arthur Robert; escape; Supt. John W. Farmery, chief of the amal gamated brigades, captain; number of men, q. Palmer, principal clerk; Stanley Groom, Robert L. W. Cooper & Charles Herbert Belbin, clerk.s; supervisors' County (formed in 1867); head quarters, 35 St. George'l; street; fire station, Rose lane; Oapt. W. G. Pidduck, office, 3a, Stour stroot; Prederick Charles Alexander, supervisor; James Higgins, officer 2 lieutenants, an engineer & 7 men. The engine is a Kent &; Canterbury Institute for Trained Nur,ses, 62 Bur Merryweather "Paxton 11 manual, & was, with all tht' gate street, W. H. Horsley esq. hon. sec.; Miss C.!". necessary appliances, supplied to th9 brigade by th, Shaw, lady superintendent directors of the County Fire Office Kent & Canterbury Hospital, Longport street, H. .A.. Kent; head quarters, 29 Westgate; engine house, Palace Gogarty M.D. physician; James Reid F.R.C.S.Eng. street, Acting Capt. Leonard Ashenden, 2 lieutenant~ T. & Frank Wacher M.R.C.S.Eng. cOJ1J8ulting surgeons; &; 6 men; appliances, I steam engine, I manual, 2 hQ5l Thomas Whitehead Reid M.RC.S.Eng. John Greasley Teel!! & 2,500 feet of hose M.RC.S.Eng. Sidney Wacher F.R.C.S.Eng. & Z. Fren Fire Escape; the City fire escape is kept at the police tice M.R.C.S. -

A Guide to Parish Registers the Kent History and Library Centre

A Guide to Parish Registers The Kent History and Library Centre Introduction This handlist includes details of original parish registers, bishops' transcripts and transcripts held at the Kent History and Library Centre and Canterbury Cathedral Archives. There is also a guide to the location of the original registers held at Medway Archives and Local Studies Centre and four other repositories holding registers for parishes that were formerly in Kent. This Guide lists parish names in alphabetical order and indicates where parish registers, bishops' transcripts and transcripts are held. Parish Registers The guide gives details of the christening, marriage and burial registers received to date. Full details of the individual registers will be found in the parish catalogues in the search room and community history area. The majority of these registers are available to view on microfilm. Many of the parish registers for the Canterbury diocese are now available on www.findmypast.co.uk access to which is free in all Kent libraries. Bishops’ Transcripts This Guide gives details of the Bishops’ Transcripts received to date. Full details of the individual registers will be found in the parish handlist in the search room and Community History area. The Bishops Transcripts for both Rochester and Canterbury diocese are held at the Kent History and Library Centre. Transcripts There is a separate guide to the transcripts available at the Kent History and Library Centre. These are mainly modern copies of register entries that have been donated to the -

Ashford Canterbury

Archaeological Investigations Project 2002 Post-Determination & Non-Planning Related Projects South East Region KENT Ashford 3/860 (E.29.F046) TQ 87003800 ASHFORD SCHOOL, EAST HILL, ASHFORD Ashford School, East Hill, Ashford, Kent. An Archaeologcial Watching Brief Report Eastbury, E London : Museum of London Archaeology Service, 2002, 16pp, figs, tabs, refs Work undertaken by: Museum of London Archaeology Service No archaeological remains were encountered. [Au(abr)] 3/861 (E.29.F077) TQ 92604670 PLUCKLEY PRIMARY SCHOOL An Archaeological Watching Brief on land at Pluckley Primary School, Pluckley, Kent Willson, J & Linklater, A Canterbury : Canterbury Archaeological Trust, 2002, 15pp, figs, tabs, refs Work undertaken by: Canterbury Archaeological Trust Very little of archaeological interest was discovered at the site, except for two pits cut into the natural subsoil. A Second World War air-raid shelter had disturbed the area. [Au(abr)] Archaeological periods represented: MO, UD Canterbury 3/862 (E.29.F076) TR 15605680 134 OLD DOVER ROAD, CANTERBURY An Archaeological Watching Brief at 134 Old Dover Road, Canterbury Willson, J Canterbury : Canterbury Archaeological Trust, 2002, 3pp, figs Work undertaken by: Canterbury Archaeological Trust Nothing of archaeological interest was found during the groundworks for a new extension. [Au(abr)] 3/863 (E.29.F085) TR 14655799 44 ST PETER'S STREET, CANTERBURY Archaeological Watching Brief of ground works to the rear of 44 St Peter's Street fronting Tower Way, Canterbury Helm, R Canterbury : Canterbury Archaeological Trust, 2002, 12pp, figs, refs Work undertaken by: Canterbury Archaeological Trust The monitoring was undertaken during the reduction of the ground surface level. Segments of a north- east/south-west aligned dwarf wall were recovered, abutting another dwarf wall that extended out of the development area. -

In This Issue Finding 21 Children: Simple—Not So Simple! Postcards from Around the World—Part III We Shall Remember Them Second Lieutenant Nassau Barrington Stephens

Quarterly Chronicle • Volume 25, Number 2 • Summer 2019 In This Issue Finding 21 Children: Simple—Not So Simple! Postcards from Around the World—Part III We Shall Remember Them Second Lieutenant Nassau Barrington Stephens Anglo-Celtic Roots This journal is published quarterly in March, June, September and December by the British Isles Family History Society of Greater Ottawa and sent free to members. Unless otherwise stated, permission to reprint for non-profit use is granted to organizations and individuals provided the source is credited. Articles accompanied by the copyright symbol (©) may not be reprinted or copied without the written permission of the author. Opinions expressed by contributors are not necessarily those of BIFHSGO or its officers, nor are commercial interests endorsed. BIFHSGO members are invited to submit family history stories, illustrations, letters, queries and similar items of interest in electronic format using MSWord-compatible software, to [email protected]. Please include a brief biographical sketch and a passport-type photograph. Authors are asked to certify that permission to reproduce any previously copyrighted material has been acquired and are encouraged to provide permission for non-profit reproduction of their articles. The Editor reserves the right to select material that meets the interest of readers and to edit for length and content. Canadian Publications Mail Sales Product Agreement No. 40015222 Indexed in the Periodical Source Index (PERSI) Editor: Barbara Tose Editors Emeritus: Jean Kitchen, Chris MacPhail Layout Designer: Barbara Tose Proofreaders: Anne Renwick, Christine Jackson, Emily Rahme British Isles Family History Society of Greater Ottawa Founded and incorporated in 1994 Charitable Registration No. -

Annual Bibliography of Kentish Archaeology and History 2008

http://kentarchaeology.org.uk/research/archaeologia-cantiana/ Kent Archaeological Society is a registered charity number 223382 © 2017 Kent Archaeological Society ANNUAL BIBLIOGRAPHY OF KENTISH ARCHAEOLOGY AND HISTORY 2008 Compiler: Ms D. Saunders, Centre for Kentish Studies. Contributors: Prehistoric - K. Partitt; Roman - Dr E. Swift, UKC; Anglo-Saxon - Dr A. Ricliardson, CAT; Medieval - Dr C. Insley, CCCU; Early Modern - Prof. J. Eales, CCCU; Modern - Dr C.W. Chalklin and Prof. D. Killingray. A bibliography of books, articles, reports, pamphlets and theses relating specifically to Kent or with significant Kentish content. All entries were published in 2008 unless otherwise stated. GENERAL AND MULTI-PERIOD M. Ballard, The English Channel: the link in the history of Kent and Pas-de- Catais (Arras: Conseil General du Pas-de-Calais, in association with KCC). P, Bennett, P. Clark, A. Hicks, J, Rady and I. Riddler, At the great crossroads: prehistoric, Roman and medieval discoveries on the Isle of Thane 11994-1995 (Canterbury: CAT Occas, Paper No. 4). C. Bumham, Hinxhill: a historical guide (Wye: Wye Historical Soc). CAT, Annual Report: Canterbury's Archaeology 2006- 7 (Canterbury). J. Hodgkinson, The Wealden iron industry (Stroud: Tempus). G, Moody, The Isle ofThanetfrom prehistory to the Norman Conquest (Stroud: Tempus). A. Nicolson, Sissinghurst, an unfinished history (London: Harper Press). J. Priestley, Eltham Palace: royalty architecture gardens vineyards parks (Chichester: Phillimore). D. Singleton, The Romney Marsh Coastline: from Hythe to Dungeness (Stroud: Sutton). M. Sparks, Canterbury Cathedral Precincts: a historical survey (Canterbury: Dean and Chapter of Canterbury, 2007). J. Wilks, Walks through history: Kent (Derby: Breedon). PREHISTORIC P. Ashbee, 'Bronze Age Gold, Amber and Shale Cups from Southern England and the European Mainland: a Review Article', Archaeotogia Cantiana, cxxvm, 249-262. -

December 2020

Westbere Parish WESTBERE PARISH COUNCIL MEETINGS AND MEETING DATES Council Regulations enabling town and parish councils to NEWSLETTER lawfully conduct virtual meetings by video and telephone conferencing until May 2021 have been published. The Local Authorities and Police and December 2020 Crime Panels (Coronavirus) (Flexibility of Local Authority and Police and Crime Panel Meetings) (England and Wales) Regulations 2020 came into Welcome to the latest edition of your Westbere force on 4 April. The legislation allows for virtual Parish Council newsletter. Any comments, meetings if required up to May 2021. suggestions or contributions for consideration in Our virtual meetings are still open to the public and we future editions would be most welcome! have an adjournment early in the agenda proceedings to give any resident the opportunity to speak. Your Parish Councillors The next virtual meeting will take place at 6pm on Vacancy (Chairman) Tuesday 19 January 2021. Stephen Laws (Vice Chairman) Sylvia Harlow This meeting will be held using Zoom as a Maria Morcom virtual hosting platform. Kathryn Wilson Members of the public may still “attend” the Karen Williams Ian McLean meeting either online or by telephone but will need to contact the Clerk for the For enquiries or reports, please contact the Clerk meeting link or phone number and the PIN in the first instance – Clerk - Amanda Sparkes: code for access to enter. 01304 365 972 [email protected] Proposed further meeting dates for 2021: Third Tuesday Canterbury City Councillors – Westbere has two of each month: 16 February, 16 March, 20 April, 18 May, ward councillors: 15 June, 20 July, No meeting in August, 21 September, Georgina Glover: 01227 711429 19 October, 16 November, No meeting in December. -

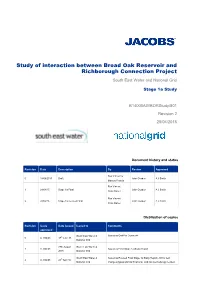

Study of Interaction Between Broad Oak Reservoir and Richborough Connection Project South East Water and National Grid

Study of interaction between Broad Oak Reservoir and Richborough Connection Project South East Water and National Grid Stage 1a Study B14000AG/BORStudy/801 Revision 2 28/04/2016 Document history and status Revision Date Description By Review Approved Ros Vincent & 0 18/06/2015 Draft John Gosden A J Smith Marcus Francis Ros Vincent 1 28/08/15 Stage 1a Final John Gosden A J Smith Chris Fisher Ros Vincent 2 28/04/16 Stage 1a Revised Final John Gosden A J Smith Chris Fisher Distribution of copies Revision Issue Date issued Issued to Comments approved South East Water & Issued as Draft for Comment 0 A J Smith 18th June 15 National Grid 28th August South East Water & 1 A J Smith Issued as Final Stage 1a Study Report 2015 National Grid South East Water & Issued as Revised Final Stage 1a Study Report - Minor text 2 A J Smith 28th April 16 National Grid changes (typos and clarifications) and risk methodology revised. Stage 1a Study Study of interaction between Broad Oak Reservoir and Richborough Connection project Project no: B14000AG Document title: Stage 1a Study Document No.: B14000AG/BORStudy/801 Revision: 2 Date: 28th April 2016 Client name: South East Water and National Grid Client no: Project manager: Alaistair Smith Author: Ros Vincent / Chris Fisher File name: B14000AG-BORStudy-801_Study of Interaction between Broad Oak Reservoir and RCP_Rev 2_Final for Issue.docx Jacobs U.K. Limited 1180 Eskdale Road Winnersh, Wokingham Reading RG41 5TU United Kingdom T +44 (0)118 946 7000 F +44 (0)118 946 7001 www.jacobs.com © Copyright 2016 Jacobs U.K. -

Annual Report 2020

Fordwich United Charities Established 1906 Registered Charity No. 208258 ANNUAL REPORT 2020 Contents Report ................................................................................................................................................................ 3 Structure, governance and management .......................................................................................................... 3 Objects ............................................................................................................................................................... 3 Trustees ............................................................................................................................................................. 3 Public benefit ..................................................................................................................................................... 3 Administration ............................................................................................................................................... 4 The year 2020 .................................................................................................................................................... 4 Covid-19 ......................................................................................................................................................... 4 Conduct of business ..................................................................................................................................... -

Kent Archives Office

http://kentarchaeology.org.uk/research/archaeologia-cantiana/ Kent Archaeological Society is a registered charity number 223382 © 2017 Kent Archaeological Society KENT ARCHIVES O.U.N10E ACCESSIONS, 1965-66 The following list comprises the principal accessions, July, 1965- July, 1966. BOROUGH RECORDS Faversham [Cat. Mk. Fa addn..]. Copies of wills and charters, 1584- 1840; Court of Orphans records, 1578-80. CINQUE PORTS RECORDS [Cat. Mk. CPw addn.]. Registrar's precedent book, 1828-60; Court of Lodemanege minutes, 1496-1808; Court of Chancery minutes, 1616-55; minutes of Lord Warden's appointments in the castles of the Ports, 1615-79; accounts for relief of debtors in Dover Castle, 1829-55. SEWERS RECORDS East Kent Commissioners [Cat. Mk. S/EK addn.]. Maps of Stour Valley from Wye to Godmersham, 1720. Teynham and Luddenham Commissioners [Cat. lVfk. S/T addn.]. Order books, 1725-91; inquisitions, 1832, 1842. TORNPTRE TRUST RECORDS New Cross Turnpike [Cat. Mk. T9 addn.j. Minutes, 1718-39. EDUCATION RECORDS Education Committees Canterbury Diocesan Education Society [Cat. Mk. DC/E]. Minutes, 1920-39; Ashford branch, minutes, 1866-1905. Dartford School Board (later Council Schools managers) [Cat. Mk. CIEB and. CIEC]. Minutes, 1874-1945. School Records [Cat. Mk. 0/ES] Bishopsbourne: log books, 1867-1951. Canterbury: Broad Street Schools, minutes, 1932-42; St. Dunstan's Infants', log books, 1885-1906; St. Dpn.ttan's Boys, log books, 1863-86; St. Dunstan's Seniors, log books, 1896-1951; Payne Smith Schools, minutes, 1896-1942; Thornton Road, log books, 1901-27. 213 KENT ARCHIVES OFFICE Darenth: Council School (later County Primary), minutes, 1903-47; Presbyterian, log book, 1875-95; Green Street Green Board School, log book, 1877-99. -

Bredlands Lane • Sturry • Canterbury • Kent • Ct2 0Hd Housetype Key

BREDLANDS LANE • STURRY • CANTERBURY • KENT • CT2 0HD HOUSETYPE KEY: CHICHESTER RIPON ELY SALISBURY DURHAM WINCHESTER LINCOLN Affordable units BREDLANDS 80 56 7 7 56 8 80 8 8 56 80 9 79 9 9 79 VV V 10 57 10 11 57 57 79 11 11 58 78 V 19 2021 22 22 23 23 58 58 78 78 PUA 7 12 10 77 18 59 PUA 13PUA14 15 16 PUA 77 77 17 19 20 21 22 23 59 59 76 76 76 60 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 60 75 75 60 75 61 74 61 74 61 74 V V 68 62 V VV 68 73 62 73 68 71 70 62 73 72 71 70 32 31 30 72 72 69 71 70 63 69 63 32 31 30 PUA 29 28 69 63 64 64 65 65 66 66 V PUA PUA PUA 33 34 64 65 66 67 67 VV 67 SPIRES ACADEMY LANE 4 3 2 1 5 6 S/S 5226 134 V 1 55 48 48 49 49 52 53 53 54 54 55 24 25 52 52 51 24 25 53 54 55 51 51 SITE LAYOUT 50 50 50 49 EXISTING HOUSING 26 48 26 26 L 47 47 HIL 27 27 47 S 27 46 46 43 42 41 NE 45 45 AI 44 T S 44 41 40 42 40 40 43 29 28 39 44 46 45 V V PUA 39 38 38 38 37 37 V 37 V N 39 36 36 36 35 35 35 33 34 ELY Living Room 5375 x 3600 17' 8" x 11' 10" Ground Floor Kitchen/Dining 5925 x 3100 (min) 19' 5" x 10' 2" (min) Bedroom 1 3675 x 2700 (min) 12' 1" x 8' 10' (min) PLOTS Bedroom 2 3375 x 2900 11' 1" x 9' 6" 64 - 68 First Floor Bedroom 3 2925 x 2000 9' 7" x 6' 7" Bedroom 4 2525 x 1975 (min) 8' 3" x 6' 6" (min) BEDROOM 3 DINING KITCHEN BEDROOM 2 GARAGE BATH EN-SUITE C * LIVING W BEDROOM 1 Side window omitted to plots 65 & 66 * WC BEDROOM 4 W Ground Floor First Floor CHICHESTER Living/Dining 4525 (max) x 4025 (max) 14' 10" (max) x 13' 2" (max) Ground Floor Kitchen 3475 x 2450 11' 5" x 8' 0" PLOTS 75 - 79 Bedroom 1 3750 (max) x 2950 12' 4" (max) x 9' 8" -

Sturry Link Road Consultation Report

Sturry Link Road Consultation Report Public Consultation 26 July – 6 September 2017 Alternative Formats This document can be made available in other formats or languages, please email [email protected] or telephone 03000 421553 (text relay service 18001 03000 421553). This number goes to an answer machine, which is monitored during office hours. Sturry Link Road Consultation Report Kent County Council Sturry Link Road Consultation Report Executive Summary that the Link Road would not reduce congestion but just move This consultation was held to present and gather feedback on it to another area. the Sturry Link Road proposals prior to submission of a detailed planning application. The Consultation took place Comments on the layout of the Link Road proposals focused over a 6 week period from 26 July to 6 September 2017 and heavily on pedestrian and cycle provisions and if the balance offered the opportunity to open a dialogue with stakeholder between all the competing transports demands were organisations and the public so their comments and concerns equitable. Examples included suggestions for additional and could be incorporated into the on-going work to finalise the wider cycle routes, segregated cycle/pedestrian provisions scheme design. and requests for more signal controlled crossings. Details of the proposals were available to view and download The proposed options for the A28/A291 junction attracted online with feedback obtained via a questionnaire which much local interest and were for many the key focal point of asked for views on the road layout, its features and its impact the consultation. Whilst most consultees understood the need on the surrounding environment including suggestions for and reasons to alter the junction, particularly the need to improvement.