Strategic Spatial Planning – a Case Study from the Greater South East of England

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Preventing the Displacement of Small Businesses Through Commercial Gentrification: Are Affordable Workspace Policies the Solution?

Planning Practice & Research ISSN: 0269-7459 (Print) 1360-0583 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/cppr20 Preventing the displacement of small businesses through commercial gentrification: are affordable workspace policies the solution? Jessica Ferm To cite this article: Jessica Ferm (2016) Preventing the displacement of small businesses through commercial gentrification: are affordable workspace policies the solution?, Planning Practice & Research, 31:4, 402-419 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02697459.2016.1198546 © 2016 The Author(s). Published by Informa UK Limited, trading as Taylor & Francis Group Published online: 30 Jun 2016. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 37 View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=cppr20 Download by: [University of London] Date: 06 July 2016, At: 01:38 PLANNING PRACTICE & RESEARCH, 2016 VOL. 31, NO. 4, 402–419 http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02697459.2016.1198546 OPEN ACCESS Preventing the displacement of small businesses through commercial gentrification: are affordable workspace policies the solution? Jessica Ferm Bartlett School of Planning, University College London, London, UK ABSTRACT KEYWORDS The displacement of small businesses in cities with rising land values Gentrification; displacement; is of increasing concern to local communities and reflected in the affordable workspace; urban literature on commercial or industrial gentrification. This article policy; small businesses explores the perception of such gentrification as both a problem and an opportunity, and considers the motivations and implications of state intervention in London, where policies requiring affordable workspace to be delivered within mixed use developments have been introduced. -

Local Planning Guidance Note No 7

LOCAL PLANNING GUIDANCE NOTE NO 7 Landscape and Development his is one of a series of local planning guidance notes amplifying development plan proposals in a clear and concise format with the objective of improving Tdesign standards. In assessing planning applications both the design of buildings and their external environment and landscape are taken into account, and on many developments, the requirement to provide a landscape scheme to the Council's approval and to subsequently implement and maintain the scheme is a condition of planning permission. The note will form a material consideration in the determination of all relevant planning applications. It is intended that this general guidance will clarify landscape information requirements and help applicants to have a better understanding of landscape issues. As these guidelines cannot cover all situations, applicants and agents are encouraged to discuss proposals with the landscape officer prior to the formal submission of an application. Information sheets are also available on a range of landscape topics. For larger or more complex sites, applicants are advised to employ a professionally qualified landscape specialist from the outset. General considerations Careful and early consideration of design issues, and the provision of adequate landscape information, as described in this leaflet, can help to avoid costly delays at a later stage. In assessing the landscape implications of planning applications the site context, proposed layout, future uses and maintenance all need to be taken into This leaflet is account. 7available in There is a diverse landscape character and settlement pattern within the County alternative formats Borough, with rural landscapes of particularly high quality or special historic landscape interest designated as Special Landscape Areas in Wrexham's Unitary Development Plan. -

Urban Planning and Urban Design

5 Urban Planning and Urban Design Coordinating Lead Author Jeffrey Raven (New York) Lead Authors Brian Stone (Atlanta), Gerald Mills (Dublin), Joel Towers (New York), Lutz Katzschner (Kassel), Mattia Federico Leone (Naples), Pascaline Gaborit (Brussels), Matei Georgescu (Tempe), Maryam Hariri (New York) Contributing Authors James Lee (Shanghai/Boston), Jeffrey LeJava (White Plains), Ayyoob Sharifi (Tsukuba/Paveh), Cristina Visconti (Naples), Andrew Rudd (Nairobi/New York) This chapter should be cited as Raven, J., Stone, B., Mills, G., Towers, J., Katzschner, L., Leone, M., Gaborit, P., Georgescu, M., and Hariri, M. (2018). Urban planning and design. In Rosenzweig, C., W. Solecki, P. Romero-Lankao, S. Mehrotra, S. Dhakal, and S. Ali Ibrahim (eds.), Climate Change and Cities: Second Assessment Report of the Urban Climate Change Research Network. Cambridge University Press. New York. 139–172 139 ARC3.2 Climate Change and Cities Embedding Climate Change in Urban Key Messages Planning and Urban Design Urban planning and urban design have a critical role to play Integrated climate change mitigation and adaptation strategies in the global response to climate change. Actions that simul- should form a core element in urban planning and urban design, taneously reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions and build taking into account local conditions. This is because decisions resilience to climate risks should be prioritized at all urban on urban form have long-term (>50 years) consequences and scales – metropolitan region, city, district/neighborhood, block, thus strongly affect a city’s capacity to reduce GHG emissions and building. This needs to be done in ways that are responsive and to respond to climate hazards over time. -

Town and Country Planning in the UK: Thirteenth Edition

TOWN AND COUNTRY PLANNING IN THE UK Thirteenth Edition This extensively revised edition of Town and Country Planning in the UK retains and enhances its reputation as the bible of British planning. The book now covers the whole of the UK and gives a critical discussion of current issues and problems. It provides an explanation of the nature of planning, the institutions and organisations involved, the plans and other tools used by planners, the system of controlling development and land use change, and planning policies pursued. Detailed consideration is given to: • The nature of planning and its historical evolution • Central and local government, the EU and other agencies • The framework of plans and other planning instruments • Development control • Land policy and planning gain • Environmental and countryside planning • Sustainable development, waste and pollution • Heritage and transport planning • Urban policies and regeneration • Planning, the profession and the public This thirteenth edition has been completely revised to take into account the many changes to the planning system and policies introduced by the Labour government. The devolution of Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland, the new instruments of regional and strategic planning, new area-based urban policy initiatives, innovation in planning for sustainable development and the rapidly expanding role of the European Union in spatial planning and environmental policy are all given comprehensive treatment in the new edition. Each chapter ends with notes on further reading and there are lists of official publications and an extensive bibliography at the end of the book. Barry Cullingworth has held academic posts at the Universities of Manchester, Durham, Glasgow, Birmingham and Toronto and is Emeritus Professor of Urban Affairs and Public Policy at the University of Delaware. -

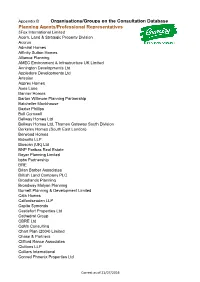

Organisations/Groups on the Consultation Database Planning

Appendix B Organisations/Groups on the Consultation Database Planning Agents/Professional Representatives 3Fox International Limited Acorn, Land & Strategic Property Division Acorus Admiral Homes Affinity Sutton Homes Alliance Planning AMEC Environment & Infrastructure UK Limited Annington Developments Ltd Appledore Developments Ltd Artesian Asprey Homes Axes Lane Banner Homes Barton Willmore Planning Partnership Batcheller Monkhouse Baxter Phillips Bell Cornwell Bellway Homes Ltd Bellway Homes Ltd, Thames Gateway South Division Berkeley Homes (South East London) Berwood Homes Bidwells LLP Bioscan (UK) Ltd BNP Paribas Real Estate Boyer Planning Limited bptw Partnership BRE Brian Barber Associates British Land Company PLC Broadlands Planning Broadway Malyan Planning Burnett Planning & Development Limited Cala Homes Calfordseaden LLP Capita Symonds Castlefort Properties Ltd Cathedral Group CBRE Ltd CgMs Consulting Chart Plan (2004) Limited Chase & Partners Clifford Rance Associates Cluttons LLP Colliers International Conrad Phoenix Properties Ltd Correct as of 21/07/2016 Conrad Ritblat Erdman Co-Operative Group Ltd., Countryside Strategic Projects plc Cranbrook Home Extensions Crest Nicholson Eastern Crest Strategic Projectsl Ltd Croudace D & M Planning Daniel Watney LLP Deloitte Real Estate DHA Planning Direct Build Services Limited DLA Town Planning Ltd dp9 DPDS Consulting Group Drivers Jonas Deloitte Dron & Wright DTZ Edwards Covell Architecture & Planning Fairclough Homes Fairview Estates (Housing) Ltd Firstplan FirstPlus Planning Limited -

Criterios De Intervención En El Patrimonio Arquitectónico Del Siglo XX Conferencia Internacional Cah20thc

MMiinniisstteerriioo CCrriitteerriiooss ddee IInntteerrvveenncciióónn eenn eell PPaattrriimmoonniioo ddee CCuullttuurraa AArrqquuiitteeccttóónniiccoo ddeell SSiigglloo XXXX CCoonnffeerreenncciiaa II nntteerrnnaacciioonnaall CCAAHH2200tthhCC.. DDooccuummeennttoo ddee MMaaddrriidd 22001111 I nnt te er rvveennttiioonn AApppprrooaacchheess iinn tthhee 2200tthh CCeennttuurryy AArrcchhiitteeccttuurraall HHeerriittaaggee II nntteerrnnaattiioonnaall CoConnffeerreennccee CCAAHH2200tthhCC.. MMaaddrriidd DoDoccuummeenntt 22001111 Criterios de Intervención en el Patrimonio Arquitectónico del Siglo XX Conferencia Internacional CAH20thC. Documento de Madrid 2011 Intervention Approaches in the 20th Century Architectural Heritage International Conference CAH20thC. Madrid Document 2011 Madrid, 14, 15 y 16 de junio de 2011 www.mcu.es Catálogo de publicaciones de la AGE http://publicacionesoficiales.boe.es/ Coordinación científica: Juan Miguel Hernández León Fernando Espinosa de los Monteros Dirección y coordinación: María Domingo Iolanda Muíña MINISTERIO DE CULTURA Edita: © SECRETARÍA GENERAL TÉCNICA Subdirección General de Publicaciones, Información y Documentación © De los textos y las fotografías: sus autores NIPO: 551-11-086-9 ISBN: 978-84-8181-505-4 Depósito legal: M-44469-2011 Imprime: Punto Verde Papel reciclado MINISTERIO DE CULTURA Ángeles González-Sinde Ministra de Cultura Mercedes E. del Palacio Tascón Subsecretaria de Cultura Ángeles Albert Directora General de Bellas Artes y Bienes Culturales Con motivo de la Conferencia Internacional sobre -

Landscape in New Developments

Development Control Policies DPD Incorporating Inspectors’ Binding Changes Local Development Framework Landscape in New Developments Supplementary Planning Document To be adopted March 2010 Published by South Cambridgeshire District Council ISBN: 0906016967 © March 2010 Gareth Jones, BSc. (Hons), MRTPI – Corporate Manager (Planning and Sustainable Communities) If you would like a copy of this document in large print or another format please contact South Cambridgeshire District Council on 03450 450 500 or email [email protected] Landscape in New Developments SPD To be adopted March 2010 CONTENTS Page Chapter 1 Introduction to the Supplementary Planning Document 1 Purpose 1 South Cambridgeshire LDF Policy 2 Chapter 2 Why a Landscape Scheme is needed 3 The scope of the landscape scheme 4 Chapter 3 The Landscape Scheme 7 When is a landscape scheme required? 7 What issues should the landscape scheme address? 7 When should the landscape scheme be submitted and what information should it 9 contain? Landscape requirements of planning applications 9 Delivering high quality Landscape 11 (1) Respecting Landscape Character 11 (2) Appropriate design 13 (3) Landscape implementation 14 (4) Landscape management and maintenance 16 (5) Encouraging biodiversity 16 (6) Sustainable Landscape schemes 18 Chapter 4 The Landscape Drawings Site survey and appraisal plans 25 Landscape concept plan 26 Detailed layout 26 Landscape design details 28 Soft landscape details 29 Hard landscape details 29 Maintenance specification and landscape management plan 30 Appendix -

'The Planned City Sweeps the Poor Away...'§: Urban Planning and 21St Century Urbanisation

Progress in Planning 72 (2009) 151–193 www.elsevier.com/locate/pplann ‘The planned city sweeps the poor away...’§: Urban planning and 21st century urbanisation Vanessa Watson * School of Architecture, Planning and Geomatics, University of Cape Town, Rondebosch, Cape Town 7700, South Africa Abstract In recent years, attention has been drawn to the fact that now more than half of the world’s population is urbanised, and the bulk of these urban dwellers are living in the global South. Many of these Southern towns and cities are dealing with crises which are compounded by rapid population growth, particularly in peri-urban areas; lack of access to shelter, infrastructure and services by predominantly poor populations; weak local governments and serious environmental issues. There is also a realisation that newer issues of climate change, resource and energy depletion, food insecurity and the current financial crisis will exacerbate present difficult conditions. As ideas that either ‘the market’ or ‘communities’ could solve these urban issues appear increasingly unrealistic, there have been suggestions for a stronger role for governments through reformed instruments of urban planning. However, agencies (such as UN-Habitat) promoting this make the point that in many parts of the world current urban planning systems are actually part of the problem: they serve to promote social and spatial exclusion, are anti-poor, and are doing little to secure environmental sustainability. Urban planning, it is argued, therefore needs fundamental review if it is to play any meaningful role in current urban issues. This paper explores the idea that urban planning has served to exclude the poor, but that it might be possible to develop new planning approaches and systems which address urban growth and the major environment and resource issues, and which are pro- poor. -

Landscape Statement

Application for Planning Permission in Principle October 2013 Landscape Statement Application for Planning Permission in Principle October 2013. Grandhome. Landscape Statement 1 2 Application for Planning Permission in Principle October 2013. Grandhome. Landscape Statement Contents 1.0 Introduction 4 1.1 Masterplan visionv 5 1.2 Document structure 5 1.3 Relevant policy 5 2.0 Existing Landscape Characteristics 6 2.1 Site context 6 2.2 Site description 6 2.3 Regional and local amenities 7 2.4 Paths and cycleways 7 2.5 Topography 8 2.6 Views and visibility 9 2.7 Aspect and shelter 11 2.8 Hydrology 12 2.9 Landscape elements, scale and character 13 2.10 Edges and boundaries 15 2.11 Tree quality 16 2.12 Ecology and Green Space Network 18 2.13 Archaeology 19 2.14 Soils 19 2.15 Technical constraints 19 2.16 Summary of opportunities and challenges 20 3.0 Landscape strategy for the PPiP area 21 3.1 Landscape concept 21 3.2 Structuring elements 22 3.3 Landscape framework 24 3.4 Planting design 29 3.5 Open Space Standards 31 Appendix 1: References 33 Appendix 2: Open Space Plans 34 Appendix 3: Open Space Provision 38 Application for Planning Permission in Principle October 2013. Grandhome. Landscape Statement 3 1. Introduction This document has been produced to support the Planning Permission in Principle (PPiP) application for the development of a new mixed use development at Grandhome, Aberdeen. It describes the landscape architecture component of the development proposals and reference should be made to the full submission and other supporting documents for detailed background information on other aspects of the application, including the description of the development proposal, the evolution of the proposal (in particular of the masterplan produced by Duany Plater-Zyberk & Co), technical considerations and the planning case that supports the wider proposal. -

Comparison of the Planning Systems in the Four UK Countries

National Assembly for Wales Research paper Comparison of the planning systems in the four UK countries January 2016 Research Service The National Assembly for Wales is the democratically elected body that represents the interests of Wales and its people, makes laws for Wales and holds the Welsh Government to account. The Research Service provides expert and impartial research and information to support Assembly Members and committees in fulfilling the scrutiny, legislative and representative functions of the National Assembly for Wales. Research Service briefings are compiled for the benefit of Assembly Members and their support staff. Authors are available to discuss the contents of these papers with Members and their staff but cannot advise members of the general public. We welcome comments on our briefings; please post or email to the addresses below. An electronic version of this paper can be found on the National Assembly website at: assembly.wales/research Further hard copies of this paper can be obtained from: Research Service National Assembly for Wales Cardiff Bay CF99 1NA Email: [email protected] Twitter: @SeneddResearch © National Assembly for Wales Commission Copyright 2016 The text of this document may be reproduced free of charge in any format or medium providing that it is reproduced accurately and not used in a misleading or derogatory context. The material must be acknowledged as copyright of the National Assembly for Wales Commission and the title of the document specified. Enquiry no: 15/02063 Paper number: 16/001 National Assembly for Wales Research paper Comparison of the planning systems in the four UK countries January 2016 Graham Winter This paper describes and compares aspects of the current land use planning systems operating in the four UK countries. -

25 February 2010 Mr G S Kaddish Bidwells Trumpington Road Cambridge CB2 9LD Your Ref: Dear Sir, TOWN and COUNTRY PLANNING

25 February 2010 Mr G S Kaddish Our Ref: APP/Q0505/A/09/2103599/NWF Bidwells APP/Q0505/A/09/2103592/NWF Trumpington Road Your Ref: Cambridge CB2 9LD Dear Sir, TOWN AND COUNTRY PLANNING ACT 1990 – SECTION 78 APPEAL BY COUNTRYSIDE PROPERTIES PLC - AT LAND BETWEEN LONG ROAD AND SHELFORD ROAD (CLAY FARM), CAMBRIDGE - Application reference 07/0621/OUT APPEAL BY COUNTRYSIDE PROPERTIES (UK) LTD - AT GLEBE FARM, SHELFORD ROAD, CAMBRIDGE - Application 08/0363/OUT 1. I am directed by the Secretary of State to say that consideration has been given to the report of the Inspector, Ava Wood DIP ARCH MRTPI, who held a public local inquiry into your clients' appeals which sat for 10 days between 28 September and 19 October 2009: Appeal A: made by Countryside Properties PLC against non-determination by Cambridge City Council (the Council) of an application for residential development of up to 2,300 new mixed-tenure dwellings and accompanying provision of community facilities and landscaped open spaces including 49ha of public open space in the green corridor, retail (A1), food and drink uses (A3, A4, A5), financial and professional services (A2), non-residential institutions (D1), a nursery (D1), alternative health treatments (D1), provision for education facilities and all related infrastructure including: all roads and associated infrastructure, alternative locations for Cambridgeshire Guide Bus stops, alternative location for CGB Landscape Ecological Mitigation Area, attenuation ponds including alternative location for Addenbrookes’ Access Road pond, cycleways, footways and crossings of Hobson’s Brook at Land between Long Road and Shelford Road (Clay Farm), Cambridge in accordance with application number 07/0621/OUT, dated 5 June 2007. -

FOI Request 7771

FOI Ref Response sent 7771 5 Oct 20 (CCC) Spend Data Thank you for publishing your spend data here https://www.cambridge.gov.uk/payments-to-suppliers. However, I notice that there isn’t any spending data published since March 2020. I'd like to make a request under the Freedom of Information Act 2000 for all transactions over £250 from April 2020 to at most a month in arrears from the date at which you publish in response to this request. Response: Thank you for your request for information above, which we have dealt with under the terms of the Freedom of Information Act 2000. I hope the following will answer your query: Please find attached the spend data requested for 2020/21. Further queries on this matter should be directed to [email protected] Body Name Supplier Name Account Number Invoice Date Document File Name Cost Centre / Project Code Cost Centre/Project Description Subjective Account Subjective description Invoice Amount (Excluding VAT) Cambridge City Council 2 Ton Productions Ltd 10326600 03/04/2020 053598 9900 Cambridge Live 20118 Receipts In Advance - Other Entities And Individuals £2,736.00 Cambridge City Council AA Global Language Services Ltd 10001100 01/03/2020 055279 1203 Corporate Policy 62408 Translation Services £717.11 Cambridge City Council ABC Food Law Ltd 10001400 14/04/2020 054332 1419 Environmental Health Operational Support 64300 Conference Expenses £1,072.50 Cambridge City Council ADC (East Anglia) Ltd 10002500 06/04/2020 053880 1883 Flood Risk Management 60501 Cleaning Services £1,875.00 Cambridge City