Town and Country Planning in the UK: Thirteenth Edition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

View in Website Mode

PS20 bus time schedule & line map PS20 Oxenhope - Parkside Secondary View In Website Mode The PS20 bus line (Oxenhope - Parkside Secondary) has 2 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Cullingworth <-> Denholme: 3:10 PM (2) Denholme <-> Cullingworth: 7:50 AM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest PS20 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next PS20 bus arriving. Direction: Cullingworth <-> Denholme PS20 bus Time Schedule 21 stops Cullingworth <-> Denholme Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday Not Operational Monday Not Operational War Memorial, Cullingworth Greenside Lane, Cullingworth Civil Parish Tuesday 3:10 PM Halifax Road Post O∆ce, Cullingworth Wednesday 3:10 PM 3 Halifax Road, Cullingworth Civil Parish Thursday 3:10 PM Halifax Rd South Road, Cullingworth Friday 3:10 PM Haworth Rd Turf Lane, Cullingworth Saturday Not Operational Haworth Road Coldspring House, Cullingworth Haworth Road Springƒeld Farm, Cullingworth PS20 bus Info Haworth Road Brownhill Farm, Flappit Spring Direction: Cullingworth <-> Denholme Stops: 21 Keighley Road Trough Ln, Cullingworth Trip Duration: 15 min Halifax Road, Cullingworth Civil Parish Line Summary: War Memorial, Cullingworth, Halifax Road Post O∆ce, Cullingworth, Halifax Rd South Keighley Rd Beech Drive, Cullingworth Road, Cullingworth, Haworth Rd Turf Lane, Cullingworth, Haworth Road Coldspring House, Keighley Rd Ogden Lane, Denholme Cullingworth, Haworth Road Springƒeld Farm, Cullingworth, Haworth Road Brownhill Farm, Flappit Spring, Keighley Road Trough Ln, Cullingworth, -

Between Wilsden & Cullingworth

Between Wilsden & Cullingworth 31/4 miles (5.2km) Circular walk Goitstock Wood e n a L s t ane n b L Hallas Hall e Na Green Close B pylon Farm Hallas Dye House Dye House Lane Cullingworth Bridge ne Ling s La alla Bents Crag seat H House Wilsden bridge k c e B d ism n an e tled d grassy rail C n w e track ay ulli ng w w e orth R H oad bridge New Laith THE Farm GR Hewenden EA T N Bridge OR TH E R N T Brown Lee Lane R A IL Station Hotel Hewenden Viaduct Hare Croft Ha wor th R oad Hewenden Reservoir Key (map not to scale) Route Station Road WALK START/FINISH Other Footpaths Hewenden Viaduct (ON STREET PARKING) Gate/Stile/Gap N City of Bradford Metropolitan District Council Countryside & Rights of Way to the left downhill, eventually walking beneath the trees. Between Wilsden & Where the tree lined path ends, climb the stile into a field and continue straight ahead across the field to a Cullingworth second stile under the tall poplar trees, which can be seen ahead. 1 3 /4 miles (5.2km) Circular walk Climb the stile and rejoin the lane, again walking beneath the trees. After only a short distance climb a third stile The walk start point is Station Road Harecroft, off over a dry stone wall out onto a farm track. Walk downhill the B6144 road between Wilsden and Cullingworth. along the track and join the surfaced country lane, Dye House Lane. -

Countryside & Rights Of

City of Bradford Metropolitan District Council Countryside & Rights of Way straight ahead across the field to a second stile under Around Cullingworth the tall poplar trees, which can be seen ahead. Here climb the stile to rejoin the lane again walking beneath 51/4 miles (8.4km) Circular walk the trees. After a short distance climb a third stile over the dry stone wall out onto a farm track, to walk the short distance along the track to join the surfaced country Walk start point is Station Road Harecroft, off the lane (Dye House Lane). B6144, between Wilsden and Cullingworth Turn left uphill here and walk along Dye House Lane, Public Transport passing a house on your right (Green Close) and the A regular hourly bus service 727 operates Monday cottages at Dye House. Just beyond the cottages the to Saturday from Keighley bus station via Morton, surfaced lane becomes a rough grassed track. Follow Bingley and Wilsden, there is no Sunday service. the track for a further 150yds (136m) to climb a stile For further details contact Metroline on 0113 245 over the wall on the right hand side, once over the stile 7676. walk down the field keeping quite close to the wall on your right and climb a second stile into the next field. Car Parking Continue by following the wall on your right until you've There is good on street parking along Station Road approached the houses ahead, here bear slightly to the Harecroft. Please park with care and consideration. left and then right down the gable end of the building at Pye Bank Farm and through a stile out onto the road Walk Information at the Junction of Nab Lane and Tan House Lane. -

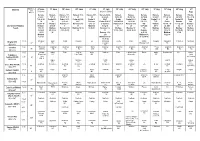

CP N2a) Five Lane Community Partnership PCN CP Chair April 2019 Code GP Practices Address Postcode Clinical Director CCG Deputy Chair (Raw

Bradford Community Partnerships and Primary Care Networks – GP Alignments (CP N1) North 1 Community Partnership PCN April CP Chair Code GP Practices Address Postcode Clinical Director CCG 2019 Deputy Chair (raw) Richmond Road, Saltaire BD18 4RX Saltaire B83040 Canon Pinnington Mews, BD16 11,360 (2 sites) Cottingley 1AQ Chair - Emma Snee Windhill Green 2 Thackley Old Road Emma Snee Districts (ANP Saltaire) (2 sites) Shipley BD18 (ANP Saltaire) Deputy – Alistair B83063 Will be merging Cliffe Avenue Baildon 1QB 12,686 McGregor with Saltaire 1st July BD17 6NT [email protected] (BVCSA Rep) 2019 B83018 Idle 440 Highfield Road, Idle BD10 11,892 8RU Total population 35,938 (CP N2a) Five Lane Community Partnership PCN CP Chair April 2019 Code GP Practices Address Postcode Clinical Director CCG Deputy Chair (raw) B83062 Ashcroft Newlands Way, Eccleshill BD10 0GE Districts 8708 B83016 Farrow 177 Otley Road, Fagley BD3 1HX Rachel Thompson Dr Alicia Taylor City 7345 B83056 Moorside 370 Dudley Hill Road, BD2 3AA (Business Manager (GP Moorside) 7737 Undercliffe Rockwell & wrose) alicia.taylor@bradford Districts B83064 Rockwell & Wrose Thorpe Edge BD10 8DP rachel.thompson2@bra .nhs.uk 10,234 (2 sites) Kings Road, Wrose BD2 1QG dford.nhs.uk Total population 34,024 (CP N2b) North 2b Community Partnership PCN April CP Chair Code GP Practices Address Postcode Clinical Director CCG 2019 Deputy Chair (raw) Haigh Hall Road, BD10 9AZ Dr Danielle B83054 Haigh Hall 5419 Greengates Hann (GP) Districts Chair TBC Shipley & Alexandra Road, Shipley BD18 [email protected] -

Comparison of the Planning Systems in the Four UK Countries

National Assembly for Wales Research paper Comparison of the planning systems in the four UK countries January 2016 Research Service The National Assembly for Wales is the democratically elected body that represents the interests of Wales and its people, makes laws for Wales and holds the Welsh Government to account. The Research Service provides expert and impartial research and information to support Assembly Members and committees in fulfilling the scrutiny, legislative and representative functions of the National Assembly for Wales. Research Service briefings are compiled for the benefit of Assembly Members and their support staff. Authors are available to discuss the contents of these papers with Members and their staff but cannot advise members of the general public. We welcome comments on our briefings; please post or email to the addresses below. An electronic version of this paper can be found on the National Assembly website at: assembly.wales/research Further hard copies of this paper can be obtained from: Research Service National Assembly for Wales Cardiff Bay CF99 1NA Email: [email protected] Twitter: @SeneddResearch © National Assembly for Wales Commission Copyright 2016 The text of this document may be reproduced free of charge in any format or medium providing that it is reproduced accurately and not used in a misleading or derogatory context. The material must be acknowledged as copyright of the National Assembly for Wales Commission and the title of the document specified. Enquiry no: 15/02063 Paper number: 16/001 National Assembly for Wales Research paper Comparison of the planning systems in the four UK countries January 2016 Graham Winter This paper describes and compares aspects of the current land use planning systems operating in the four UK countries. -

NHS England Yorkshire & Humber Orthodontic Lots and Locations

NHS England Yorkshire & Humber Orthodontic Lots and Locations Total Number Postcodes Total No. of Locations within Postcodes Lot Name Servicing (including UOA's of UOA's (including but not exclusively) but not exclusively) Lots in Lot North Yorkshire & Humber Craven BD20, BD23, BD24 Crosshills, Settle, Skipton, Craven 6500 1 6500 Grassington Harrogate HG1, HG2, HG3, Harrogate, Knaresborough, Ripon, Harrogate 10318 1 10318 HG4, HG5, YO51, Boroughbridge, Marston Moor YO26 Ward Hambleton and DL6, DL7, DL8, Leeming, Leyburn, Thirsk, Hambleton and 8606 1 8606 Richmondshire DL9, DL10, DL11, Northallerton, Richmond, Richmondshire YO7, YO61 Easingwold Scarborough YO11, YO12, Scarborough, Scalby, Seamer Scarborough and and Ryedale YO13, YO14, Ward, East Ayton, Filey, 9682 1 9682 Ryedale YO17, YO18, Hunmanby, Malton, Pickering, YO62, YO21,YO60 Helmsley, Whitby Selby YO8,LS24, LS25, Selby, Sherburn in Elmet, Selby 6500 1 6500 Tadcaster York YO1, YO10, YO19, Acomb, Bishopthorpe, York 10376 1 10376 YO23, YO24, Dunnington, Haxby, Rawcliffe, YO26, YO30, YO32 East Riding - YO15, YO16,YO25, Bridlington, Flamborough, North East HU18, HU10, Holderness Ward, East Wolds and HU11, HU12, Coastal Ward, Hornsea, Mid East Riding 19699 2 9850 HU13, HU14, Holderness Ward, North HU16, HU17, Holderness Ward, Withernsea, HU18, HU19 Hessle, Beverley, Cottingham East Riding - YO25, YO41, Pocklington, Howdenshire Ward, West YO42, YO43, Goole, Hessle, Beverley, 9850 HU10, HU13, Cottingham, Driffield HU14, HU15, HU16, HU17, DN14 Hull East HU1, HU2, HU7, Branshome, Sutton -

Bradford Areas Shipley & Surrounding Areas Free

Updated: 28/10/2015 FREE!! Community Health Champion Led Walks Please ring 01274 321911 to find out exact timings and to self refer. BRADFORD AREAS Friends of Bowling Park Bowling Park - at the hut near the Tuesdays (AM) with Barbara Pitts tennis courts off Burras Road Girlington Walk Girlington Community Centre, with Maqsood Hussain & Mohammed Wednesdays & Sundays (AM) Girlington Road, BD8 9NN Nazir St Martins Church, Haworth Road, Haworth Road meet at the community room Thursdays (AM) with David and Sharon Bass entrance at the back of the church Meeting at Hilton Road Masjid, Hilton Hilton Road Walk Education & Community Centre, Thursdays (AM) with Rehana Kauser Hilton Road, Bradford BD7 2ED Holmewood Walks Holmewood Library, Broadstone Way Mondays (AM) with Barbara Wainwright Main entrance of West End St Oswalds Walk Community Centre, Christophers Thursdays (AM) Francis Holgate Street, BD5 9DH VIP Walks (for people with visual impairments) Walks vary each month (usually With Howard England, Peter rotating between Low Moor, Lister 1st Monday of the month (AM) Kierman, David McCormack and Park and Saltaire) others SHIPLEY & SURROUNDING AREAS Baildon Corner of Westgate and Springfield with Peter & Yvonne Kierman and Wednesdays (AM) Road, Baildon Howard Lloyd Bingley Walkers Bingley Arts Centre, Main Street, Tuesdays (PM) with Brenda Hare & Ralph Harding Bingley, BD16 2LZ Bingley 2 Hour Walk Meeting point varies. with Ronda Christensen & Ralph Contact Ronda on 07929 898503 for Thursdays (PM) Harding details 2nd & 4th Tuesdays of the month (AM) Bolton Wanderers, Eccleshill Bus stop opposite Kent’s fitness, Up to 2 hours, slow paced, they with Anne Smith below Eccleshill library tend to get the bus to explore new areas. -

16 October 2019 Year 5

Keighley & Craven Schools Cross Country League 2019 - 2020 Year 5 - 6 Girls Cliffe Castle 16 October 2019 Race Pupil Number Number Pupil Name School Year Group 1 BR04 Isabella Wright Bradley Both 6 2 SIL05 Isobel Patefield Silsden 5 3 BR10 Jessica Anderson Bradley Both 5 4 NE01 Macey Plunket Nessfield 5 5 BW06 Courtney O'Connor Burley Woodhead 5 6 BUR03 Amy Gordon Burley Oaks 5 7 OX19 Sophia Casson Oxenhope 6 8 SIL02 Holly Fitch Silsden 5 9 BUR04 Dolly Gordon Burley Oaks 5 10 BUR11 Isla Arundel Burley Oaks 5 11 LL22 Tara Miller Long Lee 6 12 STAN03 Maizie Booth Stanbury 5 13 STAN01 Isla Eastham Stanbury 5 14 OA61 Lily Arnold Oakworth 5 15 BUR05 Millie Porteous Burley Oaks 5 16 STAN02 Neve Garbutt Stanbury 5 17 PW06 Afeefa Shah Parkwood 6 18 EB24 Claire Edwards Eastburn 5 19 HA10 Floss Andrews Haworth 5 20 HOL11 Megan Taylor-Chester Holycroft 5 21 STAN07 Tilly Thornton Stanbury 5 22 SIL122 Brooke Binns Silsden 5 23 LEE06 Erin Carter Lees 5 24 CW04 Liberty Wood Cullingworth 6 25 OX11 Lillie Alborne Oxenhope 6 26 CW06 Maisy Padgett Cullingworth 5 27 STAN14 Ava Sollitt Stanbury 5 28 LL10 Kaya Medica Long Lee 6 29 HA47 Ellie-May Varley Haworth 5 30 OA46 Tanya Rashid Oakworth 5 31 SIL40 Robyn Horton Silsden 5 32 SIL47 Mary Wilson Silsden 5 33 PW05 Grace Prescott Rose Parkwood 6 34 OA92 Isabella Charmbury Oakworth 6 35 EA05 Eliza Abdullah Eastwood 5 36 BR06 Holly Hampshire Bradley Both 6 37 SIL04 Umayma Saddique Silsden 5 38 EM24 L Holt East Morton 6 39 SIL36 Thea Newby Silsden 5 40 CW07 Lyla Illingworth Cullingworth 5 41 EM30 E Rogers East -

Local (Bradford and Airedale)

The following lists a range of local and national services, including confidential advice or support. Local (Bradford and Airedale) Contact Centre - 01274 200024 (sexual health information and appointments) Information Shop for Young People (under 25s) 01274 432431 Culture Fusion 125 Thornton Road, Bradford. BD1 2EP www.bradford.gov.uk/young/infoshop The Information Shop provides the following sexual health services: CASH – Mon-Wed 3.30-5.30, Sat 10-12 Friend’s Service - free condoms for under 25’s Mon-Fri 11-5.30, Sat 10-12 CASHPOINT - Mon and Wed 3.30-5.30, Sat 10-12 (No appointment needed). Free confidential advice and information on contraception, sexual health and emergency contraception and pregnancy testing. Friend’s Plus Service – Mon & Thurs 1.30-4, Tues 2-3.45, Providing advice on and testing for sexually transmitted infections for men and women. The Lads’ Room - Tues 12.30-4.30 and Thurs 3-4.30 Confidential information on drugs, alcohol, sexual health, safe sex, relationships, bullying, feeling different, provided for males by male workers, free condoms available. Keighley Connexions Centre 01535 618100 79 Low Street (near Royal Arcade) Mon-Fri 11-4.30 Trinity Centre (Sexual Health Clinic) Advice - 01274 365035 Testing/appointments - 08450020021 Trinity Road, Off Little Horton Lane, Bradford, BD5 OJD Opening Times: Mon-Fri 8.30-12 noon. No appointment necessary. Offers treatment, advice, information and counseling on all sexually transmitted infections. If symptomatic, call one of the Health Advisors (365065) for advice or to make an urgent appointment. Lilac Clinic (termination of pregnancies) 01274 364623 Bradford Royal Infirmary, Duckworth Lane, West Yorkshire, BD9 6RJ Referral for termination can be from a General Practitioner and CASH services Our Project 01274 740548 [email protected] Bradford based HIV organization offering a range support services for people affected by HIV (includes extended families and friends), social support and advice, including benefits and asylum. -

Goitstock Waterfall, Cullingworth

Goitstock Waterfall, Cullingworth STATUS: Local Geological Site OTHER DESIGNATIONS: Local Wildlife Site COUNTY: West Yorkshire DISTRICT: Bradford OS GRID REF SE 077 367 OS SHEET 1:50,000 Landranger 104 Leeds and Bradford OS SHEET: 1:25,000 Outdoor Leisure 21 South Pennines BGS Geological 1:50,000 Sheet 69 Bradford (Solid and Drift Edition) FIRST DESIGNATED by West Yorkshire RIGS Group in 1996 DATE OF MOST RECENT SURVEY West Yorkshire Geology Trust in February 2009 SCIENTIFIC INFORMATION produced by Neil Aitkenhead DESIGNATION SHEET UPDATED August 2009 SITE DESCRIPTION This is a fine example of waterfall formation by the differential weathering of the Upper Carboniferous Midgley Grit (formerly the Woodhouse Grit) and softer underlying sandy shales. The waterfall lies in a beautiful wooded amphitheatre where the boundary of the grits and shales is clearly exposed and is accessible. The gritstones contain interesting structures, including sets of cross lamination and a sharp erosive base. Goitstock Wood is recognised as having ecological importance. HISTORICAL ASSOCIATIONS: EDUCATIONAL VALUE: The site is suitable for small parties of students at all levels, wishing to study the relationship between geology and landforms. AESTHETIC CHARACTERISTICS: The falls lie in an area of pleasant woodland which has a high amenity value. ACCESS AND SAFETY: Although containing good paths, Goitstock Wood has steep valley sides, slippery rocks and deep water beneath the falls which are potentially hazardous. The site is only suitable for small, well supervised parties. Suitable footwear is essential. Park in Cullingworth and walk along the B6144 to the track leading NE to Hallas Bridge. Take the footpath along the east side of Harden Beck which leads to the falls. -

4Th June 11 June 18Th June 25Th June 2Nd

Members th th th nd th th rd th th th th th DATES 4 June 11 June 18 June 25 June 2 July 9 July 16 July 23 July 30 July 6 Aug 13 Aug 20 Aug 27 800 Pentecost Action for Children Aug Nov 16 Genesis Genesis Genesis 18:1- Genesis 21:8- Genesis 22:1- Genesis 24:34- Genesis Genesis Genesis Genesis Genesis Genesis Exodus 6:9-22; 12:1-9 15 (21: 1- 7) 21 14 38, 42-49, 25:19-34 28:10-19a 29:15-28 32:22-31 37:1-4, 12- 45:1-15 1:8 - 2:10 7:24; 8:14- Psalm 33:1- Psalm 116:1- Psalm 86:1-10, Psalm 13 58-67 Psalm Psalm 139:1- Psalm Psalm 17:1- 28 Psalm 133 Psalm 19 12 2, 12-19 16-17 Romans Psalm 45:10-17 119:105-112 12, 23-24 105:1-11, 7,15 Psalm Romans 124 Psalm 46 Romans Romans 5:1- Romans 6:1b- 6:12- 23 or Canticle: Romans 8:1- Romans 8:12- 45b Romans 105:1-6, 16- 11:1-2a, 29- Romans LECTIONARY READINGS Romans 4:13-25 8 11 Matthew Song of 11 25 or Psalm 9:1-5 22, 45b 32 12:1-8 YEAR A 1:16-17; Matthew Matthew 9:35 Matthew 10:24- 10:40-42 Solomon 2:8- Matthew Matthew 13: 128 Matthew Romans Matthew Matthew 3:22b-28 9:9-13,18- - 10:8 (9-23) 39 13 13:1-9, 18-23 24-30, 36-43 Romans 14:13-21 10:5-15 15:(10-20) 16:13-20 (9-31) 26 Romans 7:15- 8:26-39 Matthew 21-28 Matthew 25a Matthew 13: 14:22-33 7:21-29 Matthew 11:16- 31-33, 44-52 19, 25-30 Bingley (DM) 10.30 McAloon Lunn Clark Coogan LA McAloon/ Berry Raine Walls Coogan Crompton C Holmes McAloon 67 P HC Coogan Holiday Club HC BD16 4JU HC Cononley 11.00 Sharrock Anglican Anglican Anglican Walls Anglican Anglican Anglican Anglican Porter Anglican Anglican Anglican 35 MW/HC HC HC HC MW HC HC HC HC MW HC HC -

Strategic Spatial Planning – a Case Study from the Greater South East of England

The London School of Economics and Political Science Strategic spatial planning – a case study from the Greater South East of England David Church A thesis submitted to the Department of Sociology of the London School of Economics for the degree of Master of Philosophy, London, July 2015 2 Declaration I certify that the thesis I have presented for examination for the M.Phil degree of the London School of Economics and Political Science is solely my own work other than where I have clearly indicated that it is the work of others (in which case the extent of any work carried out jointly by me and any other person is clearly identified in it). The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. Quotation from it is permitted, provided that full acknowledgement is made. This thesis may not be reproduced without my prior written consent. I warrant that this authorisation does not, to the best of my belief, infringe the rights of any third party. I declare that my thesis consists of 60 973 words. 3 Abstract The aim of this thesis is to investigate, through the method of a case-study at two levels (development site and sub-region), the historical development of and current mechanisms used to deliver strategic spatial planning (large scale housing development). The theoretical underpinnings of strategic spatial planning are examined, including some key planning paradigms such as the ‘green belt’, ‘city regions’ and ‘spatial planning’. The key dichotomy of current policy – the ‘desire to devolve’ through localism and the counteracting ‘centralising tendency’ as expressed through urban containment policy is then discussed.