Tv Station Ownership and Local News Content: A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Retrans Blackouts 2010-2018

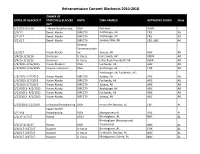

Retransmission Consent Blackouts 2010-2018 OWNER OF DATES OF BLACKOUT STATION(S) BLACKED MVPD DMA NAME(S) NETWORKS DOWN State OUT 6/12/16-9/5/16 Tribune Broadcasting DISH National WGN - 2/3/17 Denali Media DIRECTV AncHorage, AK CBS AK 9/21/17 Denali Media DIRECTV AncHorage, AK CBS AK 9/21/17 Denali Media DIRECTV Juneau-Stika, AK CBS, NBC AK General CoMMunication 12/5/17 Vision Alaska Inc. Juneau, AK ABC AK 3/4/16-3/10/16 Univision U-Verse Fort SMitH, AK KXUN AK 3/4/16-3/10/16 Univision U-Verse Little Rock-Pine Bluff, AK KLRA AK 1/2/2015-1/16/2015 Vision Alaska II DISH Fairbanks, AK ABC AK 1/2/2015-1/16/2015 Coastal Television DISH AncHorage, AK FOX AK AncHorage, AK; Fairbanks, AK; 1/5/2013-1/7/2013 Vision Alaska DIRECTV Juneau, AK ABC AK 1/5/2013-1/7/2013 Vision Alaska DIRECTV Fairbanks, AK ABC AK 1/5/2013-1/7/2013 Vision Alaska DIRECTV Juneau, AK ABC AK 3/13/2013- 4/2/2013 Vision Alaska DIRECTV AncHorage, AK ABC AK 3/13/2013- 4/2/2013 Vision Alaska DIRECTV Fairbanks, AK ABC AK 3/13/2013- 4/2/2013 Vision Alaska DIRECTV Juneau, AK ABC AK 1/23/2018-2/2/2018 Lockwood Broadcasting DISH Huntsville-Decatur, AL CW AL SagaMoreHill 5/22/18 Broadcasting DISH MontgoMery AL ABC AL 1/1/17-1/7/17 Hearst AT&T BirMingHaM, AL NBC AL BirMingHaM (Anniston and 3/3/17-4/26/17 Hearst DISH Tuscaloosa) NBC AL 3/16/17-3/27/17 RaycoM U-Verse BirMingHaM, AL FOX AL 3/16/17-3/27/17 RaycoM U-Verse Huntsville-Decatur, AL NBC AL 3/16/17-3/27/17 RaycoM U-Verse MontgoMery-SelMa, AL NBC AL Retransmission Consent Blackouts 2010-2018 6/12/16-9/5/16 Tribune Broadcasting DISH -

Broadcasters in the Internet Age

G.research, LLC November 27, 2018 One Corporate Center Rye, NY 10580-1422 g.research Tel (914) 921-5150 www.gabellisecurities.com Broadcasters in the Internet Age Brett Harriss G.research, LLC 2018 (914) 921-8335 -Please Refer To Important Disclosures On The Last Page Of This Report- G.research, LLC November 27, 2018 One Corporate Center Rye, NY 10580-1422 g.research Tel (914) 921-5150 www.gabellisecurities.com OVERVIEW The television industry is experiencing a tectonic shift of viewership from linear to on-demand viewing. Vertically integrated behemoths like Netflix and Amazon continue to grow with no end in sight. Despite this, we believe there is a place in the media ecosystem for traditional terrestrial broadcast companies. SUMMARY AND OPINION We view the broadcasters as attractive investments. We believe there is the potential for consolidation. On April 20, 2017, the FCC reinstated the Ultra High Frequency (UHF) discount giving broadcasters with UHF stations the ability to add stations without running afoul of the National Ownership Cap. More importantly, the current 39% ownership cap is under review at the FCC. Given the ubiquitous presence of the internet which foster an excess of video options and media voices, we believe the current ownership cap could be viewed as antiquated. Should the FCC substantially change the ownership cap, we would expect consolidation to accelerate. Broadcast consolidation would have the opportunity to deliver substantial synergies to the industry. We would expect both cost reductions and revenue growth, primarily in the form of increased retransmission revenue, to benefit the broadcast stations and networks. -

2012 NABJ Diversity Census an Examination of Television Newsroom Management

2012 2012 NABJ Diversity Census An examination of Television Newsroom Management By Bob Butler National Association of Black Journalists PREFACE Five years ago, in the absence of any information, NABJ set out to research and report the true state of newsroom management diversity. The result was the Television Newsroom Management Diversity Census. Many have now come to depend on this important document to determine the true health and viability of diversity within today’s newsrooms. The report is not only for the public and those who work in the industry, but also corporations and employers who are charged with assessing the realities of these circumstances. The 2012 Television Newsroom Management Diversity Census is comprised of two reports. The first report studies the diversity of news managers at 295 stations owned by different 19 companies. There are more than 700 such stations nationwide and it is our intent to eventually document every television newsroom in the country. The second report examines the diversity of newsroom managers and executives at broadcast and cable news networks. Unlike the local station, which broadcast to their respective markets, the networks provide news to the entire country. You may notice that ABC, CBS, Fox and NBC are mentioned in both reports. These networks own 51 stations that were included in the stations report. The information within the local station report is not included nor factored into the national news networks report. The demographic data retrieved is inspired by Section 257 of the amended Communications Act of 1934, which requires the FCC to “identify and eliminate, through regulatory action, market entry barriers for entrepreneurs and other small businesses in the provision and ownership of telecommunications and information services.” NABJ is the only source in the country that collects employment census data, which is a critical component in determining if those barriers exist. -

Redacted -- for Public Inspection

REDACTED -- FOR PUBLIC INSPECTION July 19, 2017 By Electronic Filing Marlene H. Dortch Secretary Federal Communications Commission 445 Twelfth Street SW Washington, D.C. 20554 Re: MB Docket No. 17-179 Tribune Media Company and Sinclair Broadcast Group, Inc. Consolidated Applications for Consent to Transfer Control Dear Ms. Dortch: Pursuant to the Protective Order in this proceeding,1 Tribune Media Company hereby submits the enclosed unredacted, Highly Confidential Information for inclusion in the record of the referenced proceeding. The enclosed submission consists entirely of Highly Confidential Information. Accordingly, pursuant to paragraph 7 of the Protective Order, access to the submission is limited to Outside Counsel and Outside Consultants and their employees who have executed and filed the Acknowledgement attached as Appendix B to the Protective Order. The information in the submission previously was included as Attachments V and VII to the Comprehensive Exhibit to the Consolidated Applications with a request for confidentiality under Section 0.459 of the Rules. It is being resubmitted herewith in conformity with the requirements of the Protective Order. Separately, also pursuant to the Protective Order, Tribune is submitting (1) two copies of the submission in an encrypted .pdf file to David Roberts of the Media Bureau, and (2) a 1 Tribune Media Company and Sinclair Broadcast Group, Inc., Consolidated Applications for Consent to Transfer Control, Protective Order, DA 17-678 (July 14, 2017) (the “Protective Order”). DC: 6472326-1 Marlene H. Dortch, Secretary July 19, 2017 Page 2 REDACTED -- FOR PUBLIC INSPECTION redacted, public version of this submission (as reflected in Attachments V and VII to the Comprehensive Exhibit) via ECFS. -

43 Annual NORTHERN CALIFORNIA AREA EMMY® AWARD NOMINATIONS ANNOUNCED

rd 43 Northern California Area Emmy® Awards 2013-2014 Updated 5/9/14 SAN FRANCISCO/NORTHERN CALIFORNIA CHAPTER rd 43 Annual NORTHERN CALIFORNIA AREA EMMY® AWARD NOMINATIONS ANNOUNCED tf The 43 Annual Northern California Area EMMY® Award Nominations were announced th Wednesday, May 7 at noon on the internet. The EMMY® award is presented for outstanding achievement in television by The National Academy of Television Arts and Sciences (NATAS). San Francisco/ Northern California is one of the twenty chapters awarding regional Emmy® statuettes. Northern California is composed of media companies and individuals from Visalia to the Oregon border and includes Hawaii and Reno, Nevada. Entries were aired during the 2013 calendar year. This year 659 English and 101 Spanish entries were received in 63 categories. English and Spanish language entries were judged and scored separately. A minimum of five peer judges from other NATAS chapters scored each entry on a scale from 1 to 10 on Content, Creativity and Execution. (Craft categories were judged on Creativity and Execution only). The total score is divided by the number of judges. The mean score is sorted from highest to lowest in each category. The Chapter Awards Committee looks at blind scores (not knowing the category) and decides on the cut off number for nominations and recipients. The results are tabulated by our accounting firm Spalding and Company. KNTV NBC Bay Area received the highest number of nominations with 40 followed by Comcast SportsNet with 28. KUVS Univision19 topped the Spanish contest with 30 nominations. In the individual nomination count all the leaders were from KNTV NBC Bay Area: Mark Villarrela with seven; Jeremy Carroll, Felipe Escamilla and Tony Kovaleski each had six. -

2011 NABJ Diversity Census

Fall 08 2011 NABJ Diversity Census An Examination of Television Newsroom Management By Bob Butler 2011 NABJ Diversity Census Volume 1: An Examination of Television Newsroom Management Author Bob Butler Edited by Phillipa Mould and Lorraine Holmes Settles Assistance provided by: Cheryl Hampton Aaron Morrison San Francisco State University Broadcast and Electronic Communications Arts Department Funding provided by The Benton Foundation © Copyright 2011 National Association of Black Journalists PRESIDENT, Gregory Lee VICE PRESIDENT – BROADCAST, Bob Butler VICE PRESIDENT – PRINT, Errin Haines SECRETARY, Lisa Cox TREASURER, Keith Reed PARLIAMENTARIAN, Cindy George EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR, Maurice Foster 1100 Knight Hall, Suite 3100, College Park, MD 20742 For copies: Please visit www.nabj.org, call (301) 405-0248 or write National Association of Black Journalists 1100 Knight Hall, Suite 3100 College Park, MD 20742 We would like to thank the Benton Foundation for funding the 2011 NABJ Diversity Census. 2011 NABJ Diversity Census: Volume 1 Table of Contents Executive Summary .................................................................................................... 1 Methodology..…………………………………………………..……………………………………………………..8 ABC ........................................................................................................................... 10 CBS ............................................................................................................................ 12 NBC .......................................................................................................................... -

Download 309630.Pdf

Case 1:14-cv-01823 Document 2-2 Filed 10/30/14 Page 1 of 17 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, Plaintiff, CASE NO. v. JUDGE: MEDIA GENERAL, INC., and FILED: LIN MEDIA LLC, Defendants. PROPOSED FINAL JUDGMENT WHEREAS, plaintiff, the United States of America filed its Complaint on October 30, 2014, and Defendant Media General, Inc. (“Media General”) and Defendant LIN Media LLC (“LIN”), by their respective attorneys, have consented to the entry of this Final Judgment without trial or adjudication of any issue of fact or law, and without this Final Judgment constituting any evidence against or admission by any party regarding any issue of fact; AND WHEREAS, Defendants agree to be bound by the provisions of this Final Judgment pending its approval by the Court; AND WHEREAS, the essence of this Final Judgment is the prompt and certain divestiture of certain rights or assets by the Defendants to assure that competition is not substantially lessened; AND WHEREAS, the United States requires Defendants to make certain divestitures for the purpose of remedying the loss of competition alleged in the Complaint; Case 1:14-cv-01823 Document 2-2 Filed 10/30/14 Page 2 of 17 AND WHEREAS, Defendants have represented to the United States that the divestitures required below can and will be made and that Defendants will later raise no claim of hardship or difficulty as grounds for asking the Court to modify any of the divestiture provisions contained below; NOW THEREFORE, before any testimony is taken, without trial or adjudication of any issue of fact or law, and upon consent of the parties, it is ORDERED, ADJUDGED, AND DECREED: I. -

Broadcast Applications 5/21/2013

Federal Communications Commission 445 Twelfth Street SW PUBLIC NOTICE Washington, D.C. 20554 News media information 202 / 418-0500 Recorded listing of releases and texts 202 / 418-2222 REPORT NO. 27993 Broadcast Applications 5/21/2013 STATE FILE NUMBER E/P CALL LETTERS APPLICANT AND LOCATION N A T U R E O F A P P L I C A T I O N AM STATION APPLICATIONS FOR ASSIGNMENT OF LICENSE ACCEPTED FOR FILING ID BAL-20130516AKH KMHI 72657 FM IDAHO CO., LLC Voluntary Assignment of License E 1240 KHZ ID , MOUNTAIN HOME From: FM IDAHO CO., LLC To: CALVARY CHAPEL OF TWIN FALLS, INC. Form 314 CLASS A TV APPLICATIONS FOR ASSIGNMENT OF LICENSE ACCEPTED FOR FILING NH BALTTA-20130516AFW W17CI 48413 CONVERGENCE Voluntary Assignment of License ENTERTAINMENT AND E CHAN-17 From: CONVERGENCE ENTERTAINMENT AND COMMUNICATIONS, COMMUNICATIONS, LLC LLC NH , CLAREMONT To: SOUND COMMUNICATIONS, LLC Form 314 TX BALTTA-20130516AGC KHPB-CA 35912 KXAN, INC. Voluntary Assignment of License E CHAN-45 TX , BASTROP From: KXAN, INC. To: KXAN, LLC Form 316 TX BALTTA-20130516AGD KHPF-CA 35923 KXAN, INC. Voluntary Assignment of License E CHAN-44 TX , FREDERICKSBURG From: KXAN, INC. To: KXAN, LLC Form 316 Page 1 of 44 Federal Communications Commission 445 Twelfth Street SW PUBLIC NOTICE Washington, D.C. 20554 News media information 202 / 418-0500 Recorded listing of releases and texts 202 / 418-2222 REPORT NO. 27993 Broadcast Applications 5/21/2013 STATE FILE NUMBER E/P CALL LETTERS APPLICANT AND LOCATION N A T U R E O F A P P L I C A T I O N CLASS A TV APPLICATIONS FOR ASSIGNMENT OF LICENSE ACCEPTED FOR FILING TX BALTTA-20130516AGE KHPL-CA 35913 KXAN, INC. -

February 23, 2011 Via ECFS Marlene Dortch Secretary Federal

A Professional Limited Liability Company Chicago Office 1333 New Hampshire Ave., NW, Fl 2 307 North Michigan Ave., Suite 1020 Washington, DC 20036 Chicago, Illinois 60601 Telephone: (202) 872-6811 Barbara S. Esbin Telephone: (312) 372-3930 Admitted in the District of Columbia Facsimile: (202) 683-6791 Facsimile: (312) 372-3939 February 23, 2011 Via ECFS Marlene Dortch Secretary Federal Communications Commission 445 12th Street, SW Room TW-A325 Washington, DC 20554 Re: American Cable Association (“ACA”) Notice of Ex Parte Presentation; In the Matter of Rulemaking to Amend The Commission’s Rules Governing Retransmission Consent; MB Docket No. 10-71. Dear Ms. Dortch: On February 22, 2011, Ross Lieberman, American Cable Association; Thomas Cohen, Kelley Drye & Warren, LLP; and the undersigned met with Joshua Cinelli, Media Advisor to Commissioner Copps; Jennifer Tatel, Legal Advisor-media issues to Commissioner Baker, Dave Grimaldi, Media Legal Advisor to Commissioner Clyburn; and Marilyn Sonn, Acting Legal Advisor for Media to Chairman Genachowski. During the meeting, ACA discussed the issues raised in its comments filed in support of the Petition for Rulemaking and as reflected in its ex parte letter filed February 16, 2011, including the matters of (i) retransmission consent price increases resulting from joint negotiations involving multiple “Big 4” (i.e., ABC, NBC, CBS, and FOX) broadcast affiliates in a single market, and (ii) retransmission consent price discrimination against smaller multichannel video programming distributors (“MVPDs”).1 ACA presented information derived from the analysis of its economic expert, Professor William P. Rogerson, Northwestern University, that was submitted with the ACA February 16th Ex Parte Letter and 1 In the Matter of Petition for Rulemaking to Amend the Commission’s Rules Governing Retransmission Consent, MB Docket No. -

VI NGUYEN [email protected] ◆ (714) 244- 7201

VI NGUYEN [email protected] ◆ (714) 244- 7201 EDUCATION DEPAUL UNIVERSITY, CHICAGO, IL (September 2006—June 2011) College of Communication Bachelor of Arts, Journalism; Minor, Biological Science EXPERIENCE WISH, MEDIA GENERAL, INDIANAPOLIS, IN (January 2015—Present) Reporter, Multimedia Journalist ♦ Report live and studio reports for weekday evening newscasts ♦ Maintain contacts and relationships for enterprise story ideas ♦ Use social media to tease to evening coverage ♦ Write stories for web using AP style KWTV, GRIFFIN COMMUNICATIONS, OKLAHOMA CITY, OK (May 2014—July 2014) Reporter, Web Content Producer ♦ Reported stories for weekend evening newscast ♦ Consistently used social media to update content from field for viewers ♦ Published stories to News9.com using AP style and maintained website KSNW, LIN MEDIA, WICHITA, KS (January 2013—February 2014) Reporter, Fill-In Anchor ♦ Reported breaking news or enterprise stories for afternoon and evening newscast ♦ Collaborated with photographers and producers to ensure quality video and audio production ♦ Participated and attended community and sponsored events on behalf of station WTVO/WQRF, NEXSTAR BROADCASTING GROUP, ROCKFORD, IL (October 2011—January 2013) Multimedia Journalist, Fill-In Anchor ♦ Shot, wrote, edited, and web stories as one-man-band under strict deadline ♦ Served as fill in anchor and produced various newscast when assigned ♦ Enterprise daily story ideas and developed contacts within community WLS-TV, WALT DISNEY COMPANY, CHICAGO, IL (January 2011—June 2011) Political -

Promoting Local Tv in a Post-Network World

PROMOTING LOCAL TV IN A POST-NETWORK WORLD: EXAMINING DIFFERENCES IN SOCIAL MEDIA PRACTICES A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE MASTER OF ARTS IN DIGITAL STORYTELLING BY MICHAEL M. BROUDER DR. ROBERT A. BROOKEY - ADVISOR BALL STATE UNIVERSITY MUNCIE, INDIANA DECEMBER 2016 ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract…………………………………………………………………………….…. v Acknowledgements…………………………………………………...………………. vi Chapter 1: TV Goes Social…………………………………………………….……. 1 Introduction A Network’s “Nose” for Social Media Television as We Knew It The Digital Transformation Measuring the Post-Network Audience Evolving Behaviors: Social Media, Mobile and TV Evolving Relationships: Networks and Their Affiliates Social Media and Television A Call for More Study Theory and Method Chapter Preview Chapter 2: Large Market Observations…………………………………………… 24 Introduction Big Markets, Big Social Footprint Sweeping Up Ratings Through Social Media Facebook: Different Platform, Different Content Facebook Live and the Super Bowl WABC-TV & KGO-TV: Same Ownership, Contrasts in Execution Twitter and Breaking News iii WPIX: Social Media with a Twist Promotion: Digital to Digital or Digital to TV? Large Market Summary Chapter 3: Medium Market Observations………………………………………… 44 Introduction Sizing Up Social Media Media Consolidation and the Duopoly Structure, Workflow and Social Efforts at Duopoly Stations Staffing for Digital Content in Mid-Sized Markets The Evolution of Social Media Use in Mid-Sized Markets Impressions Versus Engagement Snackable Content Facebook Live Mornings Mean More (Social) Media Medium Market Summary Chapter 4: Small Market Observations ……………………………………………. 62 Introduction Markets in Contrast The Small Market Social Media Scorecard All Hands on Deck: The Team Approach to Small Market Twitter Use Small Market Use of Facebook and Facebook Live Getting into the Act at the Oscars Small Market Summary iv Chapter 5: Discussion………………………………………………...………….….. -

Competitive Impact Statement: U.S. V. Media General, Inc. and LIN Media

Case 1:14-cv-01823 Document 3 Filed 10/30/14 Page 1 of 19 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, Plaintiff, CASE NO. v. JUDGE: MEDIA GENERAL, INC., and FILED: LIN MEDIA LLC, Defendants. COMPETITIVE IMPACT STATEMENT Pursuant to Section 2(b) of the Antitrust Procedures and Penalties Act (“APPA” or “Tunney Act”), 15 U.S.C. § 16(b)-(h), plaintiff United States of America (“United States”) files this Competitive Impact Statement relating to the proposed Final Judgment submitted for entry in this civil antitrust proceeding. I. NATURE AND PURPOSE OF THE PROCEEDING Defendants Media General, Inc. (“Media General”) and LIN Media LLC (“LIN”) entered into a Purchase Agreement, dated March 21, 2014, pursuant to which Media General would acquire LIN. Under the Purchase Agreement, LIN shareholders would receive approximately $1.5 billion in a combination of stock and cash. Defendants compete head-to-head in the sale of broadcast television spot advertising in the following Designated Market Areas (“DMAs”): Mobile, Alabama/Pensacola, Florida; Birmingham, Alabama; Savannah, Georgia; Providence, Rhode Island/New Bedford, Massachusetts; and Green Bay/Appleton, Wisconsin (collectively “the DMA Markets”). Case 1:14-cv-01823 Document 3 Filed 10/30/14 Page 2 of 19 The United States filed a civil antitrust Complaint on October 30, 2014, seeking to enjoin the proposed acquisition. The Complaint alleges that the likely effect of the acquisition would be to lessen competition substantially and increase broadcast television spot advertising prices in each of the DMA Markets in violation of Section 7 of the Clayton Act, 15 U.S.C.