Promoting Local Tv in a Post-Network World

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

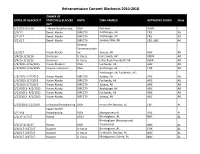

Retrans Blackouts 2010-2018

Retransmission Consent Blackouts 2010-2018 OWNER OF DATES OF BLACKOUT STATION(S) BLACKED MVPD DMA NAME(S) NETWORKS DOWN State OUT 6/12/16-9/5/16 Tribune Broadcasting DISH National WGN - 2/3/17 Denali Media DIRECTV AncHorage, AK CBS AK 9/21/17 Denali Media DIRECTV AncHorage, AK CBS AK 9/21/17 Denali Media DIRECTV Juneau-Stika, AK CBS, NBC AK General CoMMunication 12/5/17 Vision Alaska Inc. Juneau, AK ABC AK 3/4/16-3/10/16 Univision U-Verse Fort SMitH, AK KXUN AK 3/4/16-3/10/16 Univision U-Verse Little Rock-Pine Bluff, AK KLRA AK 1/2/2015-1/16/2015 Vision Alaska II DISH Fairbanks, AK ABC AK 1/2/2015-1/16/2015 Coastal Television DISH AncHorage, AK FOX AK AncHorage, AK; Fairbanks, AK; 1/5/2013-1/7/2013 Vision Alaska DIRECTV Juneau, AK ABC AK 1/5/2013-1/7/2013 Vision Alaska DIRECTV Fairbanks, AK ABC AK 1/5/2013-1/7/2013 Vision Alaska DIRECTV Juneau, AK ABC AK 3/13/2013- 4/2/2013 Vision Alaska DIRECTV AncHorage, AK ABC AK 3/13/2013- 4/2/2013 Vision Alaska DIRECTV Fairbanks, AK ABC AK 3/13/2013- 4/2/2013 Vision Alaska DIRECTV Juneau, AK ABC AK 1/23/2018-2/2/2018 Lockwood Broadcasting DISH Huntsville-Decatur, AL CW AL SagaMoreHill 5/22/18 Broadcasting DISH MontgoMery AL ABC AL 1/1/17-1/7/17 Hearst AT&T BirMingHaM, AL NBC AL BirMingHaM (Anniston and 3/3/17-4/26/17 Hearst DISH Tuscaloosa) NBC AL 3/16/17-3/27/17 RaycoM U-Verse BirMingHaM, AL FOX AL 3/16/17-3/27/17 RaycoM U-Verse Huntsville-Decatur, AL NBC AL 3/16/17-3/27/17 RaycoM U-Verse MontgoMery-SelMa, AL NBC AL Retransmission Consent Blackouts 2010-2018 6/12/16-9/5/16 Tribune Broadcasting DISH -

Collecting Lombardi's Dominating Packers

Collecting Lombardi’s Dominating Packers BY DAVID LEE ince Lombardi called Lambeau Field his “pride and joy.” Specifically, the ground itself—the grass and the dirt. V He loved that field because it was his. He controlled everything that happened there. It was the home where Lombardi built one of the greatest sports dynasties of all-time. Fittingly, Lambeau Field was the setting for the 1967 NFL Champion- ship, famously dubbed “The Ice Bowl” before the game even started. Tem- peratures plummeting to 12 degrees below zero blasted Lombardi’s field. Despite his best efforts using an elaborate underground heating system to keep it from freezing, the field provided the perfect rock-hard setting to cap Green Bay’s decade of dominance—a franchise that bullied the NFL for nine seasons. The messy game came down to a goal line play of inches with 16 seconds left, the Packers trailing the Cowboys 17-14. Running backs were slipping on the ice, and time was running out. So, quarterback Bart Starr called his last timeout, and ran to the sideline to tell Lombardi he wanted to run it in himself. It was a risky all-in gamble on third down. “Well then run it, and let’s get the hell out of here,” Starr said Lom- bardi told him. The famous lunge into the endzone gave the Packers their third-straight NFL title (their fifth in the decade) and a second-straight trip to the Super Bowl to face the AFL’s best. It was the end of Lombardi’s historic run as Green Bay’s coach. -

Federal Register/Vol. 85, No. 103/Thursday, May 28, 2020

32256 Federal Register / Vol. 85, No. 103 / Thursday, May 28, 2020 / Proposed Rules FEDERAL COMMUNICATIONS closes-headquarters-open-window-and- presentation of data or arguments COMMISSION changes-hand-delivery-policy. already reflected in the presenter’s 7. During the time the Commission’s written comments, memoranda, or other 47 CFR Part 1 building is closed to the general public filings in the proceeding, the presenter [MD Docket Nos. 19–105; MD Docket Nos. and until further notice, if more than may provide citations to such data or 20–105; FCC 20–64; FRS 16780] one docket or rulemaking number arguments in his or her prior comments, appears in the caption of a proceeding, memoranda, or other filings (specifying Assessment and Collection of paper filers need not submit two the relevant page and/or paragraph Regulatory Fees for Fiscal Year 2020. additional copies for each additional numbers where such data or arguments docket or rulemaking number; an can be found) in lieu of summarizing AGENCY: Federal Communications original and one copy are sufficient. them in the memorandum. Documents Commission. For detailed instructions for shown or given to Commission staff ACTION: Notice of proposed rulemaking. submitting comments and additional during ex parte meetings are deemed to be written ex parte presentations and SUMMARY: In this document, the Federal information on the rulemaking process, must be filed consistent with section Communications Commission see the SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION 1.1206(b) of the Commission’s rules. In (Commission) seeks comment on several section of this document. proceedings governed by section 1.49(f) proposals that will impact FY 2020 FOR FURTHER INFORMATION CONTACT: of the Commission’s rules or for which regulatory fees. -

Matador Band Students Compete, Perform the Matador Band Performed at the Annual Band Boost- Er Barbecue Fundraiser on Nov 10

A Publication of the Seguin ISD Fine Arts Department February 2018 Matador Band students compete, perform The Matador Band performed at the annual Band Boost- er Barbecue Fundraiser on Nov 10. All Seguin ISD band students performed at the event, which raised money for supporting the district’s growing band program. The Mata- dor Band performed in the Holiday Stroll parade on Nov 30. Small ensembles played for events such as the KWED Holiday Food and Toy Drive on Dec. 8. The high school band’s holiday concert on Dec. 14 featured the Wind En- semble, Wind Symphony, and Symphonic Band. The middle school bands from both Barnes and Briesemeister performed at the Performance Arts Center on Dec. 12, which included per- formances by the beginners, 7th and 8th grade concert bands. Competition continued for band students through the TMEA All State Band audition process that began in the fall. Fifty-three students competed, and forty earned All District Band chairs. Thirty of those students placed high enough to earn a chair in the All Region Bands, which performed in concert on January 21. Fifteen students earned positions in the All Area Band and advanced to the All State Band au- ditions on Jan 7. Twelve students were awarded Region Orchestra chairs and performed a concert on Dec 10. Performances of both the Region Band concert and Region Orchestra concert were excellent! Briesemeister band students Christian Bertling and Kayla Hinton earned chairs in the South Zone Band through auditions on Nov. 11. They performed in the Region Band concert on Dec. -

Ed Phelps Logs His 1,000 DTV Station Using Just Himself and His DTV Box. No Autologger Needed

The Magazine for TV and FM DXers October 2020 The Official Publication of the Worldwide TV-FM DX Association Being in the right place at just the right time… WKMJ RF 34 Ed Phelps logs his 1,000th DTV Station using just himself and his DTV Box. No autologger needed. THE VHF-UHF DIGEST The Worldwide TV-FM DX Association Serving the TV, FM, 30-50mhz Utility and Weather Radio DXer since 1968 THE VHF-UHF DIGEST IS THE OFFICIAL PUBLICATION OF THE WORLDWIDE TV-FM DX ASSOCIATION DEDICATED TO THE OBSERVATION AND STUDY OF THE PROPAGATION OF LONG DISTANCE TELEVISION AND FM BROADCASTING SIGNALS AT VHF AND UHF. WTFDA IS GOVERNED BY A BOARD OF DIRECTORS: DOUG SMITH, SAUL CHERNOS, KEITH MCGINNIS, JAMES THOMAS AND MIKE BUGAJ Treasurer: Keith McGinnis wtfda.org/info Webmaster: Tim McVey Forum Site Administrator: Chris Cervantez Creative Director: Saul Chernos Editorial Staff: Jeff Kruszka, Keith McGinnis, Fred Nordquist, Nick Langan, Doug Smith, John Zondlo and Mike Bugaj The WTFDA Board of Directors Doug Smith Saul Chernos James Thomas Keith McGinnis Mike Bugaj [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Renewals by mail: Send to WTFDA, P.O. Box 501, Somersville, CT 06072. Check or MO for $10 payable to WTFDA. Renewals by Paypal: Send your dues ($10USD) from the Paypal website to [email protected] or go to https://www.paypal.me/WTFDA and type 10.00 or 20.00 for two years in the box. Our WTFDA.org website webmaster is Tim McVey, [email protected]. -

The Ice Bowl: the Cold Truth About Football's Most Unforgettable Game

SPORTS | FOOTBALL $16.95 GRUVER An insightful, bone-chilling replay of pro football’s greatest game. “ ” The Ice Bowl —Gordon Forbes, pro football editor, USA Today It was so cold... THE DAY OF THE ICE BOWL GAME WAS SO COLD, the referees’ whistles wouldn’t work; so cold, the reporters’ coffee froze in the press booth; so cold, fans built small fires in the concrete and metal stands; so cold, TV cables froze and photographers didn’t dare touch the metal of their equipment; so cold, the game was as much about survival as it was Most Unforgettable Game About Football’s The Cold Truth about skill and strategy. ON NEW YEAR’S EVE, 1967, the Dallas Cowboys and the Green Bay Packers met for a classic NFL championship game, played on a frozen field in sub-zero weather. The “Ice Bowl” challenged every skill of these two great teams. Here’s the whole story, based on dozens of interviews with people who were there—on the field and off—told by author Ed Gruver with passion, suspense, wit, and accuracy. The Ice Bowl also details the history of two legendary coaches, Tom Landry and Vince Lombardi, and the philosophies that made them the fiercest of football rivals. Here, too, are the players’ stories of endurance, drive, and strategy. Gruver puts the reader on the field in a game that ended with a play that surprised even those who executed it. Includes diagrams, photos, game and season statistics, and complete Ice Bowl play-by-play Cheers for The Ice Bowl A hundred myths and misconceptions about the Ice Bowl have been answered. -

©2008 Hammett & Edison, Inc. TV Station KABB • Analog Channel 29

TV Station KABB · Analog Channel 29, DTV Channel 30 · San Antonio, TX Expected Change In Coverage: Post-Transition Appendix B Facility Appendix B (solid): 1000 kW ERP at 441 m HAAT, Network: Fox vs. Analog (dashed): 5000 kW ERP at 443 m HAAT, Network: Fox Market: San Antonio, TX Menard Mason Llano Burnet Milam Williamson TX-31 Taylor Kimble Round Rock Burleson TX-11 TX-10 Gillespie Blanco Austin Lee Travis Edwards Kerr Bastrop Kerrville Hays TX-21 Kendall San Marcos Caldwell Fayette Real Bandera Comal New Braunfels TX-25 Colorado Guadalupe TX-20 San Antonio Gonzales Bexar Uvalde Lavaca Medina TX-23 A29 D30 Uvalde Wilson DeWitt Jackson Zavala Frio Atascosa Karnes TX-14 Victoria Victoria Goliad TX-28 Calhoun TX-15 Dimmit Beeville La Salle McMullen Bee Live Oak Refugio Aransas Webb San Patricio Duval Jim Wells TX-27 2008 Hammett & Edison, Inc. Nueces 10 MI 0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 100 80 60 40 20 0 KM 20 Coverage gained after DTV transition (no symbol) No change in coverage KABB Appendix B TV Station KCWX · Analog Channel 2, DTV Channel 5 · Fredericksburg, TX Expected Change In Coverage: Granted Construction Permit CP (solid): 23.7 kW ERP at 412 m HAAT vs. Analog (dashed): 100 kW ERP at 413 m HAAT Market: San Antonio, TX Runnels Coleman Brown Hamilton Tom Green Mills McLennan Gatesville TX-17 Coryell Concho Falls Lampasas McCulloch San Saba Killeen Temple Bell TX-11 Schleicher Menard TX-31 Burnet Milam Mason Llano Williamson Sutton Kimble Round Rock Lee Gillespie Blanco Austin TX-10 Fredericksburg Travis Edwards A2 D5 Kerr Bastrop Kerrville Hays Kendall TX-21 San Marcos Caldwell Real Comal Fayette Bandera TX-25 New Braunfels Guadalupe TX-20 Kinney San Antonio Gonzales Bexar Lavaca Uvalde Medina TX-23 Wilson DeWitt Maverick TX-28 TX-15 TX-14 Atascosa Zavala Frio Karnes Victoria Goliad 2008 Hammett & Edison, Inc. -

NCHA Regular Season Champion

1997 Final Eight 1998 Final Eight 1999 Final Eight 2002 Final Eight 2003 Frozen Four 2004 Runner-Up 2005 Final Eight 2006 Runner-Up 2007 Frozen Four NCHA Regular Season Champion 1997 2002 2005 1998 2003 2006 1999 2004 2007 NCHA Peters Cup Champion 1998 2003 2005 1999 2004 2007 GENERAL INFORMATION Table of Contents Championships . 1 Staff Directory General Information . 2 About St. Norbert College . 3-4 Mailing address: Schuldes Sports Center Head Coach Tim Coghlin . 5 St. Norbert College Assistant Coaches. 6 100 Grant St. 2007-08 Roster . 7 De Pere, WI 54115-2099 Hockey Outlook . 8 The 2007-08 Green Knights. 9-13 All telephone numbers are area code 920 Knights of the Round Table . 14 NCHA Information . 15-16 William Hynes 2006-07 Statistics . 17-18 STAFF President 2006-07 Game Summaries . 23-25 Athletics Director Cornerstone Community Center . 26 Tim Bald (Loras, 1980) . .403-3031 St. Norbert All-Americans . 27-28 Assistant Athletics Director Honors and Awards . 29-30 Connie Tilley (UW-La Crosse, 1974) . .403-3033 All-Time Leaders . 31 Sports Information Director All-Time Records . 32-34 Dan Lukes (UW-Oshkosh, 1998) . .403-4077 Year-By-Year Statistics. 35 All-Time Results . 36-37 Certified Athletic Trainers All-Time Rosters. 38-40 Russ Schmelzer (St. Norbert, 1981) . .403-3179 Media Information. 41 Ryan Vandervest (UW-Oshkosh, 2002) . .403-3179 Sportsmanship. 42 Administrative Assistants Pat Duffy . .403-3031 Jodi Schleis (Cardinal Stritch, 1999) . .403-3921 Michael Marsden Dean of the College Quick Facts VP - Academic Affairs Location: De Pere, Wisconsin 54115 Founded: 1898 COACHES Enrollment: 2,100 Baseball Tom Winske (Fort Hays State, 1988) . -

WEEK 12 San Fran.Qxd

THE DOPE SHEET OFFICIAL PUBLICITY, GREEN BAY PROFESSIONAL FOOTBALL CLUB VOL. V; NO. 17 GREEN BAY, NOV. 18, 2003 11th GAME PACKERS CAPTURE TEAM RUSHING LEAD: The NFL’s best teams, since Sept. 27, 1992 Packers last weekend swiped from Baltimore the title of league’s No. 1 rushing offense (166.5 yards per game). Brett Favre made his first start at quarterback — and first of a league-record 200 in consecutive fashion — Sept. 27, 1992, vs. Pittsburgh. The NFL’s top X Green Bay hasn’t finished a season leading the NFL in teams since that day: rushing since 1964 (150.4). The team hasn’t finished in the Top 5 since 1967, when they won the Ice Bowl. And, Team W L T Pct Super Bowls Playoff App. the Packers haven’t ranked in the Top 10 since they San Francisco 120 63 0 .656 1 9 Green Bay 120 63 0 .656 2 8 were seventh in 1972. Pittsburgh 109 73 1 .598 1 8 X The Packers have paced the NFL in rushing three other Miami 110 74 0 .598 0 8 times: 1946, when future Hall of Famer Tony Canadeo Denver 109 74 0 .596 2 5 shined in a deep backfield, and 1961-62, when Vince Kansas City 109 74 0 .596 0 5 Minnesota 107 76 0 .585 0 8 Lombardi’s feared Green Bay Sweep dominated the Hou./Ten. 105 78 0 .574 1 5 game and led the Packers to consecutive world champi- Dallas 102 81 0 .557 3 7 onships. -

All Full-Power Television Stations by Dma, Indicating Those Terminating Analog Service Before Or on February 17, 2009

ALL FULL-POWER TELEVISION STATIONS BY DMA, INDICATING THOSE TERMINATING ANALOG SERVICE BEFORE OR ON FEBRUARY 17, 2009. (As of 2/20/09) NITE HARD NITE LITE SHIP PRE ON DMA CITY ST NETWORK CALLSIGN LITE PLUS WVR 2/17 2/17 LICENSEE ABILENE-SWEETWATER ABILENE TX NBC KRBC-TV MISSION BROADCASTING, INC. ABILENE-SWEETWATER ABILENE TX CBS KTAB-TV NEXSTAR BROADCASTING, INC. ABILENE-SWEETWATER ABILENE TX FOX KXVA X SAGE BROADCASTING CORPORATION ABILENE-SWEETWATER SNYDER TX N/A KPCB X PRIME TIME CHRISTIAN BROADCASTING, INC ABILENE-SWEETWATER SWEETWATER TX ABC/CW (DIGITALKTXS-TV ONLY) BLUESTONE LICENSE HOLDINGS INC. ALBANY ALBANY GA NBC WALB WALB LICENSE SUBSIDIARY, LLC ALBANY ALBANY GA FOX WFXL BARRINGTON ALBANY LICENSE LLC ALBANY CORDELE GA IND WSST-TV SUNBELT-SOUTH TELECOMMUNICATIONS LTD ALBANY DAWSON GA PBS WACS-TV X GEORGIA PUBLIC TELECOMMUNICATIONS COMMISSION ALBANY PELHAM GA PBS WABW-TV X GEORGIA PUBLIC TELECOMMUNICATIONS COMMISSION ALBANY VALDOSTA GA CBS WSWG X GRAY TELEVISION LICENSEE, LLC ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY ADAMS MA ABC WCDC-TV YOUNG BROADCASTING OF ALBANY, INC. ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY ALBANY NY NBC WNYT WNYT-TV, LLC ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY ALBANY NY ABC WTEN YOUNG BROADCASTING OF ALBANY, INC. ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY ALBANY NY FOX WXXA-TV NEWPORT TELEVISION LICENSE LLC ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY AMSTERDAM NY N/A WYPX PAXSON ALBANY LICENSE, INC. ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY PITTSFIELD MA MYTV WNYA VENTURE TECHNOLOGIES GROUP, LLC ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY SCHENECTADY NY CW WCWN FREEDOM BROADCASTING OF NEW YORK LICENSEE, L.L.C. ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY SCHENECTADY NY PBS WMHT WMHT EDUCATIONAL TELECOMMUNICATIONS ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY SCHENECTADY NY CBS WRGB FREEDOM BROADCASTING OF NEW YORK LICENSEE, L.L.C. -

Broadcasters in the Internet Age

G.research, LLC November 27, 2018 One Corporate Center Rye, NY 10580-1422 g.research Tel (914) 921-5150 www.gabellisecurities.com Broadcasters in the Internet Age Brett Harriss G.research, LLC 2018 (914) 921-8335 -Please Refer To Important Disclosures On The Last Page Of This Report- G.research, LLC November 27, 2018 One Corporate Center Rye, NY 10580-1422 g.research Tel (914) 921-5150 www.gabellisecurities.com OVERVIEW The television industry is experiencing a tectonic shift of viewership from linear to on-demand viewing. Vertically integrated behemoths like Netflix and Amazon continue to grow with no end in sight. Despite this, we believe there is a place in the media ecosystem for traditional terrestrial broadcast companies. SUMMARY AND OPINION We view the broadcasters as attractive investments. We believe there is the potential for consolidation. On April 20, 2017, the FCC reinstated the Ultra High Frequency (UHF) discount giving broadcasters with UHF stations the ability to add stations without running afoul of the National Ownership Cap. More importantly, the current 39% ownership cap is under review at the FCC. Given the ubiquitous presence of the internet which foster an excess of video options and media voices, we believe the current ownership cap could be viewed as antiquated. Should the FCC substantially change the ownership cap, we would expect consolidation to accelerate. Broadcast consolidation would have the opportunity to deliver substantial synergies to the industry. We would expect both cost reductions and revenue growth, primarily in the form of increased retransmission revenue, to benefit the broadcast stations and networks. -

2012 NABJ Diversity Census an Examination of Television Newsroom Management

2012 2012 NABJ Diversity Census An examination of Television Newsroom Management By Bob Butler National Association of Black Journalists PREFACE Five years ago, in the absence of any information, NABJ set out to research and report the true state of newsroom management diversity. The result was the Television Newsroom Management Diversity Census. Many have now come to depend on this important document to determine the true health and viability of diversity within today’s newsrooms. The report is not only for the public and those who work in the industry, but also corporations and employers who are charged with assessing the realities of these circumstances. The 2012 Television Newsroom Management Diversity Census is comprised of two reports. The first report studies the diversity of news managers at 295 stations owned by different 19 companies. There are more than 700 such stations nationwide and it is our intent to eventually document every television newsroom in the country. The second report examines the diversity of newsroom managers and executives at broadcast and cable news networks. Unlike the local station, which broadcast to their respective markets, the networks provide news to the entire country. You may notice that ABC, CBS, Fox and NBC are mentioned in both reports. These networks own 51 stations that were included in the stations report. The information within the local station report is not included nor factored into the national news networks report. The demographic data retrieved is inspired by Section 257 of the amended Communications Act of 1934, which requires the FCC to “identify and eliminate, through regulatory action, market entry barriers for entrepreneurs and other small businesses in the provision and ownership of telecommunications and information services.” NABJ is the only source in the country that collects employment census data, which is a critical component in determining if those barriers exist.